KOLUMN Magazine

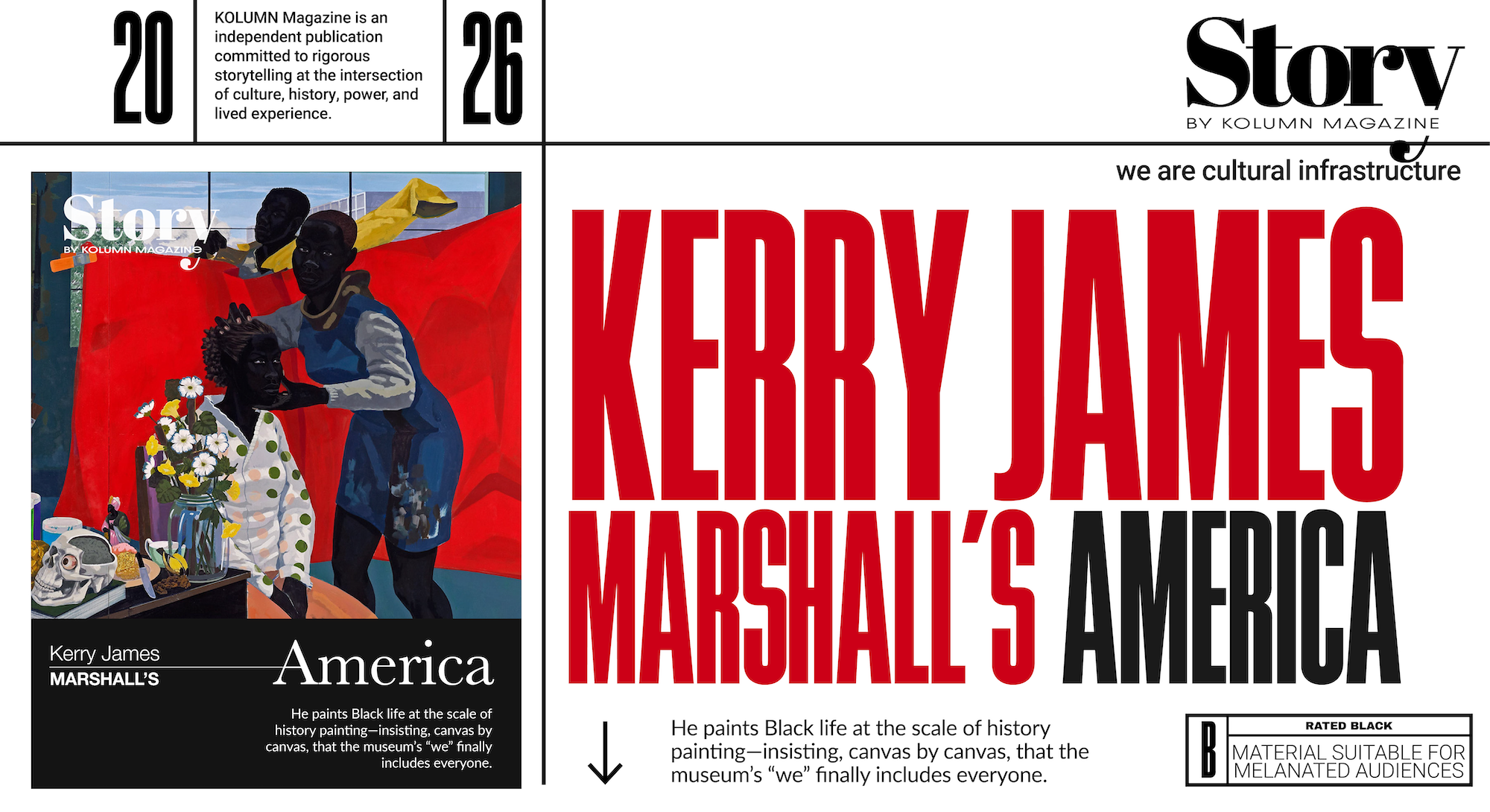

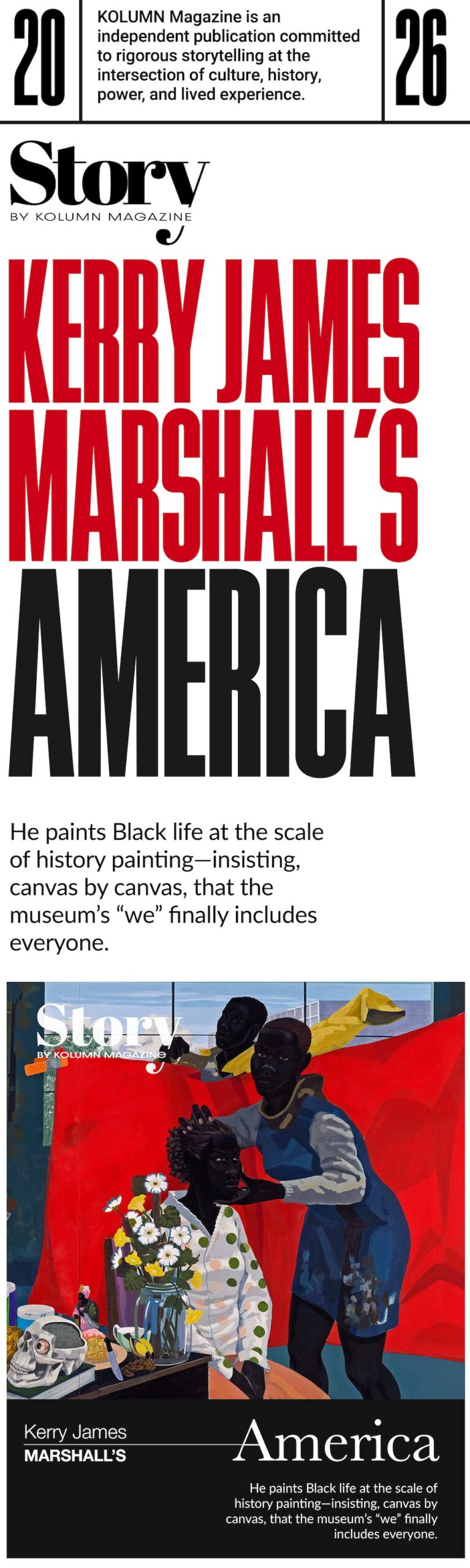

Marshall paints Black life at the scale of history painting—insisting, canvas by canvas, that the museum’s “we” finally includes everyone.

Marshall paints Black life at the scale of history painting—insisting, canvas by canvas, that the museum’s “we” finally includes everyone.

By KOLUMN Magazine

In the economy of museums—what hangs, what gets conserved, what becomes the visual shorthand for an era—absence is rarely described as a decision. It is more often dressed up as inheritance: a collection’s “history,” a canon’s “tradition,” the quiet tyranny of what has always been there. Kerry James Marshall has made a career out of treating that alibi with suspicion. He has approached painting like an instrument built to register social fact, and the social fact he refuses to let American culture evade is straightforward: the story of modern life, told through art, has too often behaved as if Black people were peripheral to the picture or altogether outside the frame.

Marshall’s response is not a small correction, not an illustrative addendum, not the tasteful cameo of diversity in a gallery otherwise devoted to the old gods of Europe. It is a full-scale counterproposal: paintings that are big enough—physically, rhetorically, historically—to compete with the genres that once made Blackness either invisible or ornamental. This is one reason his work has come to feel less like a “body of paintings” than like a sustained civic project. When the Metropolitan Museum of Art described the retrospective “Kerry James Marshall: Mastry” as revealing a practice that synthesizes traditions in order to counter stereotypical representations and reassert Black presence within Western painting’s canon, it was not marketing language so much as a plain description of what the paintings do when you stand in front of them: they pressure the viewer’s assumptions about who painting is for and what painting is capable of holding.

The insistence is there from the start. Marshall, born in 1955 in Birmingham, Alabama, grew up in a period when the racial order of the United States was contested in the streets, in courtrooms, and on television screens. Later, his family moved to Los Angeles, to the Watts area and the Nickerson Gardens public housing project; the terrain of his youth was shaped by both the promise of Black community and the blunt facts of segregation by other means. It is easy, in retrospect, to narrate this as destiny: Birmingham, the civil-rights era, Los Angeles in the shadow of the Watts uprising. But Marshall’s art does not merely “reflect” those origins. It translates them into a visual language that is at once learned and defiant: a command of Western composition, genre, and art-historical quotation deployed on behalf of subjects that Western painting had long treated as marginal.

That translation took a particular kind of stubbornness. In the decades when much contemporary art education trained students to distrust painting—when installation, conceptual practice, and new media were commonly treated as the serious future—Marshall did not abandon the medium that had most thoroughly policed representation. He doubled down. He pursued what he and sympathetic critics have framed as “mastery,” not as a conservative retreat but as a strategic occupation: if painting remained one of the core machines through which cultural prestige was made, then painting was also one of the core machines through which it could be remade. The Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago’s framing of “Mastry” emphasized precisely this: a multi-decade practice in which Marshall synthesized traditions to reassert the Black figure’s place inside the canon that had excluded it.

To call Marshall’s project “representation” risks making it sound like a simple matter of depiction: paint Black people, and the problem is solved. But his work argues that depiction is not neutral; it comes bundled with the visual habits of centuries. So he does not simply place Black figures into inherited scenes. He interrogates the inherited scenes themselves—pastoral leisure, history painting, portraiture, even abstraction—and then rebuilds them with different assumptions about who belongs there and what their presence should mean.

That is why the figures in Marshall’s paintings are often rendered in a black so deep it feels less like a skin tone than a proposition. The blackness is not incidental. It is, in a sense, the whole argument, made visible: Blackness that will not be softened for comfort, Blackness that will not be reduced to a “range” that merely flatters the viewer’s expectation. In interviews and institutional materials, Marshall has repeatedly described his determination to make Black presence in the museum “not negotiable,” a phrase that captures the ethical posture of the work: it refuses the conditional acceptance historically extended to Black artists—accepted if palatable, accepted if modest, accepted if grateful.

The question, then, is not only how Marshall became one of the most influential painters of his generation. It is also how he turned painting—often dismissed as a relic—into an arena where the politics of visibility, the aesthetics of pleasure, and the moral weight of history can coexist without collapsing into propaganda. Marshall’s significance lives in that balance: he can make a painting that is gorgeous in color and composition while also making it difficult in implication; he can stage scenes of joy that are not naïve about what joy costs.

A Childhood in the Wake of History

Biographical narratives about artists can become a kind of sentimental trap: the childhood trauma that “explains” the mature work; the neighborhood that “produced” the vision. Marshall’s story resists that packaging because it is not simply a story of hardship overcome. It is a story of attention trained early—attention to power, to images, to the way public life scripts private lives.

Born in Birmingham in 1955, Marshall entered the world at a time when the civil-rights movement was not yet a commemorative language of national virtue but an ongoing confrontation with violence. When his family later moved to Los Angeles, he lived in the Watts district and near the Nickerson Gardens housing project, environments shaped by both the density of Black community life and the precariousness produced by housing policy, policing, and economic exclusion. His proximity to Black political activism—often noted in accounts of his early life—did not give him a ready-made ideology so much as it gave him a sense that cultural work and civic work were not cleanly separable.

This matters because Marshall’s paintings are rarely content with the private interiority of the “artist’s soul.” They tend to treat the social world as the true studio: the barbershop as an arena of style and performance; the public-housing courtyard as a site where the pastoral tradition can be tested; the beauty salon as an institution of aesthetic labor. In Marshall’s hands, these spaces become stages where ordinary gestures acquire epic dignity.

The artist’s later move to Chicago—where he has lived and worked for decades, and where he taught at the University of Illinois at Chicago—cemented another aspect of his sensibility: a commitment to place, to neighborhood institutions, to the idea that cultural production is not only for the global circuit but also for local publics. His long partnership with the playwright, director, and actor Cheryl Lynn Bruce is often mentioned in biographical accounts not as gossip but as context: Marshall’s social world is populated by other makers, other interpreters, other people committed to craft.

None of this guarantees the paintings. Plenty of artists come from politically charged environments and produce work that is politically inert. Marshall’s distinction is that he treats painting itself as an engine of power—an art form that historically trained viewers to see certain bodies as heroic, certain scenes as universal, certain lives as worthy of monumental scale. His project is to redirect that engine.

Painting as Correction, Painting as Seduction

The temptation, when discussing Marshall, is to praise the politics and then treat the paintings as illustrations. But the paintings do not work if you disregard their formal intelligence. Marshall’s art is persuasive partly because it is pleasurable: because it understands how viewers fall in love with pictures.

Consider his approach to genre. When museums speak of his synthesis of “pictorial traditions,” they are naming a real fluency: Marshall can quote Renaissance annunciations, modernist grids, French pastoral scenes, American realist narrative, and the graphic punch of advertising. He uses acrylic, collage, and sometimes glitter not as decorative gimmicks but as tools for building a surface that can carry multiple registers at once: the seduction of color, the sharpness of symbol, the conceptual bite of juxtaposition.

This is why “Mastry” mattered so much. The exhibition—co-organized by major institutions and described by the Met as the largest museum retrospective of his work to date—gathered decades of painting into a single argument: that Marshall is not merely a “Black artist” making work for a niche audience; he is an artist working on the central questions of Western art history, from inside the medium most associated with that history. The show’s scale—nearly 80 works, including dozens of paintings spanning roughly 35 years—was itself a declaration that his career belonged to the category of the major, the canonical, the museum-defining.

Writers who have spent time in his orbit often emphasize the deliberate quality of his practice: the sense that nothing is casual, that each compositional decision is part of a larger program. In a long New Yorker profile, Marshall is described as an artist whose mastery across landscape, portraiture, and history painting draws from deep knowledge of Western art history, while centering the Black experience and confronting its historical underrepresentation in museums. The profile’s central point is not that Marshall “finally got recognized,” though it notes the surge of attention around 2016; it is that the recognition arrived because the work had long been doing what institutions were slow to admit they needed: building a visual world where Black presence is not a sociological footnote but the organizing principle.

Yet Marshall’s work also refuses a simplistic reading in which “Blackness” automatically equals “trauma.” One of the most telling aspects of his practice—explicitly noted in interviews and criticism—is his decision not to make spectacle out of Black suffering as the primary way to secure empathy. Instead, he paints Black life as fully human: funny, vain, tender, ordinary, stylish, bored, radiant. A Financial Times profile framed this as part of his broader project: the paintings hold “radiant blackness” within narratives that range from salons and picnics to meditations on slavery and the Middle Passage, refusing the idea that Black life can be reduced to a single emotional note.

That refusal is political in the deepest sense because it contests a long-standing contract between white audiences and Black subjects: the contract in which Black pain becomes the price of admission into visibility. Marshall’s paintings ask viewers to pay attention without demanding that the subject bleed for it.

The Barbershop, the Beauty Salon, and the Monument of Everyday Life

One of Marshall’s most famous paintings, “De Style” (1993), is often described as a breakthrough because it clarifies his ambition: to take a setting associated with ordinary community life and render it at the scale of history painting. In the NPR profile of Marshall’s retrospective-era moment, the curator Helen Molesworth called “De Style” his “first great painting,” emphasizing how it offers an image of Black daily life that is both rooted in everyday pleasure and “transcendent” at the same time.

The barbershop in “De Style” is not simply a barbershop. It is a theater of Black masculinity, a laboratory of style, a space where the artistry of grooming is treated as a cousin to the artistry of painting itself. Marshall famously adds a halo to the barber—an iconographic move that elevates the craft of the hands, the “mad” skill, into something like sainthood. In doing so, he also flips a hierarchy: the museum has long treated the “fine artist” as the maker worthy of reverence. Marshall suggests that the community’s makers—the barber, the stylist—have always been artists; the museum has simply lacked the eyes to see them.

A similar logic animates works like “School of Beauty, School of Culture” (2012), which—again, in the NPR account—Molesworth describes as monumental, bursting with riotous color, spirited life, and an expansive notion of beauty not confined to whiteness. The beauty salon in Marshall’s hands becomes a counter-institution to the gallery: a place where aesthetic judgment is practiced, where labor produces glamour, where people rehearse the politics of appearance and self-possession.

These scenes are not escapist. They are, rather, Marshall’s way of making a claim about what counts as worthy subject matter. For centuries, European painting lavished seriousness on aristocratic portraits, mythological tableaux, and pastoral leisure—often treating Black figures as servants, ornaments, or exotic accessories. Marshall reverses the terms: he gives Black subjects the pictorial dignity historically reserved for the elite, without stripping away the specificity of their cultural context. The result is a kind of democratic grandeur, an epic of the everyday.

The Garden Project and the Public Housing Pastoral

Marshall’s “Garden Project” series makes the stakes of his method even clearer. The pastoral tradition in Western art—sunlit leisure, lush landscapes, bodies at ease—has frequently functioned as an aesthetic fantasy: a world where labor and conflict disappear into scenery. Marshall’s insight was to recognize that Black American life has its own forms of communal pleasure and pastoral aspiration, even in places designed by policy to be anything but idyllic.

In a widely cited discussion of the series, Marshall described having the pastoral tradition in mind while making paintings of people eating lunch and listening to music—“only this time the setting is a public housing project for African American families.” The point is not to romanticize public housing. It is to expose the gap between the euphemistic naming of these developments—so often called “gardens”—and the lived reality of the residents. Marshall’s paintings live inside that gap. They show the beauty people make under constraint, and they refuse to let the built environment be read only as failure.

The title “Many Mansions,” for example, carries the double register of aspiration and irony: a biblical echo and a public-housing address. Marshall’s palette in these works can be jubilant—greens, pinks, bright skies—while the compositions still carry the weight of systemic neglect. This is one of his signature abilities: to let pleasure remain pleasure while still allowing history to be present as pressure.

It is also in this series that Marshall’s larger project becomes unmistakable: he is not simply inserting Black figures into existing genres; he is revising the genres so that the social world they once ignored becomes central.

Souvenirs and the Work of Memorial

If the barbershops and salons are Marshall’s monuments to living culture, the “Souvenir” series is his sustained engagement with memory—particularly the memory of the civil-rights era and the costs of liberation struggle. The Seattle Art Museum’s “Figuring History” materials describe the “Souvenir” paintings as history paintings about the 1960s, commemorating the civil-rights movement and Black liberation struggle while paying tribute to individuals murdered or lost during that period.

The series often stages a domestic interior infused with mourning and reverence: names, dates, glittering text, and symbolic imagery that merges the language of celebration with the language of elegy. The glitter—so easily dismissed as decorative—becomes a complex material here, capable of carrying both the kitsch of commemorative objects and the radiance of sanctification. These works insist that memory in Black America is not confined to formal monuments; it lives in homes, in keepsakes, in the visual culture of remembrance.

What distinguishes Marshall’s memorial approach is that it does not freeze history into piety. The “Souvenir” paintings can be lush, even seductive, while still naming death. They belong to a lineage of history painting that includes both the grand moral tableaux of European tradition and the intimate commemorations of community memory. In Marshall’s hands, the genre becomes a vehicle for honoring lives the official record has often diminished.

Recognition, Markets, and the Problem of Value

Marshall’s institutional recognition has been long in the making, but the wider public conversation about him intensified around the mid-2010s, when museums staged the kind of retrospective usually reserved for artists already canonized. “Mastry,” traveling from the MCA Chicago to the Met Breuer and to MOCA Los Angeles, was widely treated as a landmark: a museum-level acknowledgment that Marshall’s project had reshaped contemporary painting.

Then came the market spectacle. In 2018, Marshall’s painting “Past Times” sold at auction for $21.1 million, widely reported as a record for a work by a living African-American artist. The sale triggered a predictable cycle of headlines: the “firsts,” the record-breaking price, the breathless astonishment that a Black painter could command numbers long normalized for white contemporaries.

There are at least two ways to read such a moment. One is celebratory: Marshall, after decades of disciplined work, finally receives market validation commensurate with his institutional stature. Another is skeptical: a market that for years undervalued Black artists suddenly discovers them, often in a frenzy that benefits collectors and intermediaries as much as it benefits the artists themselves. The Art Newspaper noted the staggering rise in value of “Past Times” across decades, a detail that underscores how “value” is less a natural property of art than a product of institutions, gatekeeping, and timing. (Art Newspaper)

Marshall himself has tended to treat the market as neither salvation nor proof. The more interesting question for him has always been where the work lives: whether it enters museums, whether it exists “alongside everything else” visitors go to museums to see. This is not a naïve stance; it is a strategic one. Museums are not neutral, but they remain one of the primary engines of cultural legitimacy. If Marshall wants Black presence to become “indispensable” within the art historical record, the museum remains a battlefield worth contesting.

It is also worth noting that the market narrative—record price, celebrity bidding rumors, the frenzy of wealth—can obscure the deeper scandal Marshall’s work exposes: that Black painters had been producing masterwork-level art for generations without comparable valuation. The real story is not that Marshall sold for $21.1 million. The real story is that so much Black brilliance was historically priced, collected, and discussed as if it were peripheral.

Marshall’s Method: Art History as Material

To understand Marshall’s significance, you have to understand his relationship to art history. For him, art history is not a passive archive; it is active material. He borrows, quotes, parodies, and sometimes battles the old masters not because he wishes to flatter them but because he recognizes their authority as a social fact. The canon is not merely a list of great works; it is a training system for perception. If you change the pictures that define “greatness,” you change what viewers learn to see as universal.

This is why his paintings often feel like arguments staged as images. They can contain modernist grids that recall Mondrian, Rococo flourishes that echo ornamental pleasure, Renaissance compositional strategies that confer sanctity, and American realist details that root scenes in lived space. The effect is not academic. It is theatrical. Marshall uses the authority of these traditions to authorize subjects the traditions excluded.

Art21, in its framing of Marshall’s project, has described him as driven to centralize the Black figure in order to change perceptions of beauty and representation—an approach that treats painting as a platform for ideas rather than a private diary. This is consistent with Marshall’s own public statements: he tends to speak about images as tools that shape what people believe is possible.

That tool-like understanding of art also appears in discussions of his newer and more hybrid projects, such as “Rythm Mastr,” described in the New Yorker as an ambitious multimedia undertaking blending graphic novel, animation, and live-action film. Even here, the impulse is consistent: to create a visual world expansive enough to carry Black imagination without asking permission from the inherited institutions of culture.

Complexity Without Comfort: New Work and Harder Histories

One reason Marshall’s work remains urgent is that it refuses to settle into the role institutions often prefer for “important” Black artists: the role of moral ornament, the respectable chronicler of Black suffering, the safe symbol of progress. Marshall is increasingly willing to make work that complicates the narratives viewers bring with them.

A recent Guardian interview about his newer paintings—works that depict Black enslavers and confront African participation in the transatlantic slave trade—frames Marshall as resisting simplistic moral binaries, insisting that art should be capable of holding uncomfortable truths rather than soothing myths. In a cultural moment when political discourse often collapses history into slogans, Marshall pushes in the opposite direction: toward complexity, toward moral difficulty, toward the recognition that agency and complicity do not always align with the stories nations tell about themselves.

This is not a departure from his earlier work so much as an intensification of a long-standing principle: that Black life in painting should not be reduced to a single script. The Financial Times review of his Royal Academy exhibition “The Histories” emphasizes that his work moves from celebrations of everyday life to haunting meditations on slavery, juxtaposing beauty and memory with aesthetic brilliance and historical force.

To some viewers, this range can feel like contradiction. How can the painter of barbershops and picnics also be a painter of the Middle Passage’s echo? The answer is that Marshall refuses the idea that Black history can be partitioned into separate museums: joy in one wing, grief in another, politics behind glass. The same society that produces a beauty salon also produces a historical archive of violence; the same community that dances also mourns. Marshall’s paintings insist that these truths coexist.

The Stakes of Seeing

What, finally, is Marshall’s significance? It is not only that he has painted Black people into museums. It is that he has made the museum’s omissions visible as omissions—made them feel less like “history” and more like a set of choices that can be challenged.

In the NPR profile, Marshall’s language is blunt: the goal was to ensure the paintings entered museums so they could exist alongside “everything else” people go to museums to see. This is not merely about inclusion as a feel-good gesture. It is about the structure of public memory. Museums teach people what a society values; they teach which lives are worthy of contemplation; they teach which images are allowed to stand for “humanity.” When Black people are absent from that visual curriculum—or present only in subordinate roles—the absence becomes a lesson.

Marshall’s paintings reverse that lesson. They do not ask to be accommodated by the canon; they behave as if they are already part of it, and the canon is simply catching up. That posture—confident, rigorous, unsentimental—has influenced a generation of artists who now treat Black figuration not as a genre category but as a field of formal invention and historical contestation. Even critics writing about broader movements of Black figurative art often cite Marshall as a foundational figure whose work set terms for what came next.

There is another kind of significance as well, harder to quantify: Marshall has helped expand what viewers believe painting can do. In a period when painting has been declared dead and then resurrected so many times it begins to sound like a cliché, Marshall has used painting to do something more demanding than mere survival. He has used it as a technology for re-educating vision.

He does this not through lectures but through seduction—through color, scale, surface, and the deep pleasure of looking. The paintings draw you in. Then, once you are inside their world, they force a recognition: that the world you thought you knew, the canon you thought was natural, was built with exclusions that can no longer be tolerated as background.

In that sense, Marshall’s career is not only an artistic achievement. It is a civic one. He has made it harder—visually, institutionally, morally—for American culture to pretend that Black life is secondary to the grand narrative. He has built a body of work that functions like an alternative archive: not an archive of documents, but an archive of images powerful enough to compete with the images that shaped the old story.

And because these paintings are not content to flatter the viewer’s conscience—because they are often funny, lush, difficult, and formally exacting—they do not merely persuade. They endure.