Pressley’s political fight for the economic equality of women is not a single bill or a single speech. It is the cumulative work of trying to make the economy answer a different question than it usually does. Not “how fast can it grow,” or “how cheaply can it run,” but: who gets to live with dignity?

Pressley’s political fight for the economic equality of women is not a single bill or a single speech. It is the cumulative work of trying to make the economy answer a different question than it usually does. Not “how fast can it grow,” or “how cheaply can it run,” but: who gets to live with dignity?

By KOLUMN Magazine

On a cold logic chart, politics is the art of coalition and compromise: a slow conversion of demands into line items, a patient translation of pain into program design. In lived reality, politics is more often the moment when a woman—tired, underpaid, and asked to be grateful for the minimum—realizes the system is not simply ignoring her. It is built to extract from her.

Ayanna Pressley has spent her public life arguing that the extraction is not incidental. It is structural. And in her telling, the clearest evidence is the economic position of Black women: the workers most likely to be essential and least likely to be protected; the caregivers who underwrite other people’s mobility while their own remains stalled; the borrowers who take on debt as a bridge and find the bridge rigged with tolls; the mothers who are told the nation reveres them and then forced to navigate maternity care deserts and punitive workplace policies; the survivors who are praised for resilience instead of given justice. If you want to see how a society values women, Pressley suggests, watch what it pays them, what it forgives, what it funds, and what it forces them to endure.

The throughline of her career—through Boston City Hall and into Congress—has been a consistent insistence that “women’s issues” are not niche concerns. They are the economic core. And because Black women sit at the intersection of racial hierarchy, gendered labor expectations, and policy neglect, Pressley has used their lived experience as both a moral compass and an evaluative tool: if the policy doesn’t move the material conditions of Black women, it is not noting the problem hard enough.

That framing is not only rhetorical. It has shaped her committee work, her priorities, and the mix of bills and public pressure campaigns she embraces: job guarantees and debt relief, fare-free public transit and anti-eviction protections, maternal health and equal rights advocacy, oversight of corruption and demands for ethical accountability. The agenda can look sprawling to critics who prefer clean categories. Pressley’s answer, over and over, is that the people who carry the most vulnerability do not live in categories. They live in compounding realities.

The making of a politics that starts with women

Pressley was born in 1974 in Cincinnati and raised in Chicago, a geography that matters because it locates her origin story in two American cities with long records of segregation, labor stratification, and political machines that have often treated Black communities as both indispensable voting blocs and disposable constituencies.

Her biography is frequently described in the compressed language of public profiles: a single mother who worked multiple jobs; a father who struggled with addiction and was incarcerated for much of Pressley’s childhood; a young woman who arrived in Boston and navigated school and work at the same time. But the details Pressley returns to—when she chooses to narrate herself rather than be narrated—are about the intersection of vulnerability and responsibility, especially the forms of responsibility placed on girls and women.

Her mother, Sandra Pressley, supported the household through multiple jobs and, according to biographical accounts, also did community organizing work tied to tenants’ rights. It is hard to miss the imprint: housing stability as a political question, not an individual virtue; women’s labor as both survival and civic glue. In later years, Pressley would speak of the people “closest to the pain” needing to be “closest to the power,” a phrase that became something like an operating theory for her politics. The line is often quoted as inspiration, but it is also a governing premise: you cannot fix what you refuse to listen to.

Her early adulthood in Boston included time at Boston University and work that, in some accounts, required leaving formal education to support her family after her mother lost a job. This is a familiar American narrative—education interrupted by economic necessity—but Pressley’s later policy obsessions make it clear she does not treat it as a rite of passage. She treats it as an indictment: a country that frames upward mobility as individual grit while requiring that grit disproportionately from Black women.

More than that, Pressley has chosen to speak publicly about surviving sexual violence, including childhood sexual abuse and sexual assault, a disclosure that is both deeply personal and politically consequential in a culture that routinely demands women translate trauma into palatable testimony before institutions will respond. In recent years, she has reiterated that survivorship is not a credential but a reality that shapes how she approaches accountability, law enforcement, and the slow machinery of public institutions.

These elements—economic precarity, gendered responsibility, and survival—are not the entire story of Pressley’s ascent, but they are central to how she explains her “why.” And they help explain why, even when the national press frames her as a progressive “insurgent,” she often sounds less like a romantic revolutionary than like a woman describing a set of practical repairs that have been postponed for decades.

Learning power from the inside before contesting it

Pressley’s first major political jobs were not on the outside of the system but within it. After leaving BU, she worked for Representative Joseph P. Kennedy II, moving from internship to district office work and into more senior roles. She later became a senior aide and political director for Senator John Kerry.

This matters for two reasons. First, it complicates the false narrative of Pressley as an “outsider” whose authority rests solely on moral clarity. She learned the mechanics: casework, scheduling, coalition maintenance, the rhythms of constituency service, and the silent vetoes that committees and leadership can impose. Second, it shaped her later argument that empathy is not enough; you need levers. Pressley has always talked about movement politics and community voice, but she pairs it with an operator’s understanding that, absent power, pain becomes a recurring anecdote rather than a policy outcome.

That blend—movement language with institutional fluency—would become her signature style, and it would also become the basis for her claim that the Democratic Party’s greatest risk is not “going too big,” but going too small. In a Washington Post interview about her role inside the progressive movement, Pressley argued that what persuades voters is impact, and that policy should go “as broad and as deep as the hurt is.”

The statement is more than a line. It is a theory of political failure: if Democrats promise structural change and deliver narrow relief, they will not be credited for moderation. They will be blamed for betrayal. In Pressley’s view, that betrayal is felt most intensely by people who already live on the edge of solvency—disproportionately, Black women.

City Hall: Turning “women’s issues” into the agenda

Pressley first won a seat on the Boston City Council in 2009 and served from 2010 to 2019, an at-large councilor in a city where neighborhood inequality and demographic change are often negotiated through euphemism. In many profiles, the historical milestone is highlighted: she became the first woman of color to serve in the Boston City Council’s then-century-long history.

But the more revealing element is what she chose to prioritize. As a councilor, Pressley created a focus on women and families through institutional mechanisms—like the Committee on Healthy Women, Families, and Communities—that made it harder for “women’s issues” to be treated as ceremonial.

In the fine print of municipal governance, committees can be symbolic. In Pressley’s approach, they were used as a platform to insist that violence prevention, human trafficking, child welfare, and health education were not peripheral topics but public safety and economic stability issues. The logic is straightforward: when women are unsafe, when children are neglected, when trauma is untreated, the cost shows up everywhere—emergency rooms, schools, workplaces, and the criminal legal system. City budgets end up paying for dysfunction because they refused to pay for prevention.

Pressley also coauthored a 2014 ordinance aimed at preventing discrimination in city contracting tied to insurers, including protections related to gender identity and expression—an early indication that her definition of “women” and “families” was not limited to the most politically comfortable constituencies.

Even her municipal work on credit and employment—such as opposing the use of credit scores in hiring decisions—foreshadowed her later congressional agenda. Credit scores are one of those technocratic tools that present themselves as neutral, despite being deeply shaped by historical inequities. When employers use credit to judge “character,” they import the consequences of predatory lending, medical debt, and income volatility into the job market—punishing workers for the very precarity the economy produces. That sort of policy target is classic Pressley: a hidden structure that quietly penalizes people already carrying racial and gendered burdens.

In Boston, she learned how these burdens show up on the ground—evictions, wage theft, healthcare gaps, transit inequities—and how women often become the shock absorbers. The single mother who takes a second job to cover childcare. The grandmother who becomes the default caregiver. The service worker who stays late because tips make rent, and then gets punished when a boss decides she is replaceable.

Pressley’s later fights in Congress would scale up, but they would remain recognizable as the national versions of what she watched locally: a public sector that can either cushion or compound private exploitation.

The upset that became a signal

In 2018, Pressley challenged Representative Mike Capuano, a long-serving incumbent, in the Democratic primary for Massachusetts’s 7th congressional district. She won, in what became one of the cycle’s most discussed upsets. The Atlantic’s analysis of the victory treated it as evidence that politics had become less “local” in the old sense—less about lineage and accent, more about ideological identity and moral narrative. Another Atlantic piece published days earlier framed the race as emblematic of a left increasingly hungry for “lived experience,” not just progressive voting records.

Pressley’s district itself sharpened the argument. Her official biography emphasizes that the Massachusetts 7th is both the most diverse and the most unequal district in the state, a juxtaposition that makes a mockery of triumphal narratives about liberal New England. Pressley didn’t need to import inequality into the story; it was the story. Her political bet was that representation and policy urgency were not aesthetic concerns, but governing necessities in a district where racial and economic fault lines are visible.

She went on to become the first Black woman elected to Congress from Massachusetts. And very quickly, she was grouped with other high-profile progressive women—Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Ilhan Omar, Rashida Tlaib—in what the press dubbed “the Squad.” Pressley has both embraced and complicated that label. She has described the “Squad” less as a club than as a wide coalition: anyone interested in building a more equitable and just world, she suggested, is part of it.

The framing matters because Pressley’s core pitch is not personal brand or ideological purity. It is an insistence that a politics centered on marginalized people is not factionalism; it is democracy doing its job.

A champion of women means building an economic agenda that treats women as central

Pressley’s opponents sometimes try to reduce her emphasis on women—especially Black women—to identity rhetoric. The strongest rebuttal is her policy map: she treats economic equality for Black women as a multi-front fight, because Black women’s economic reality is shaped by multiple systems at once.

There is the labor market, where Black women are often clustered in sectors that are underpaid and overexposed to volatility. There is the care economy, where unpaid caregiving work quietly subsidizes both employers and the state. There is the credit and debt system, where borrowing becomes a tool for survival and then a trap. There is public infrastructure—transit, housing, healthcare—that can determine whether a job is possible to keep. And there is violence and trauma, which can shatter earning power while institutions ask survivors to endure the burden alone.

Pressley’s rhetorical skill is to make these systems legible as one story, not five. She does not just call for “more opportunity.” She names the specific policy levers that determine whether a Black woman can move from survival to stability.

The job guarantee argument: full employment as gender justice

One of the clearest windows into Pressley’s economic worldview is her sustained push for a federal job guarantee. She introduced a House resolution in 2021 recognizing a duty of the federal government to create a job guarantee. Her office and public materials describe the project as both a safety net and a structural correction—good-paying jobs with benefits, implemented locally, intended to close racial and gender income gaps.

In 2024, she returned to the idea again, unveiling a federal job guarantee resolution during Black History Month and explicitly situating it in a lineage of Black women and civil rights leaders.

It is not difficult to see why she frames this as central to Black women’s equality. A job guarantee is a direct confrontation with the labor market’s implicit bargaining structure: employers can underpay and mistreat workers, in part, because unemployment and underemployment make workers desperate. Black women—overrepresented in “essential” work and in public-facing service roles—are especially exposed to that dynamic. A job guarantee is a policy attempt to change the bargaining floor.

The Root reported in early 2024 that Pressley was planning what it described as an “Economic Bill of Rights,” with guaranteed jobs as a central element, invoking civil rights-era visions of full employment. Read as a political strategy, it is Pressley trying to reframe “economic equality” away from narrow wage-gap talk and toward a more fundamental question: is the economy organized to ensure dignified work is available, or to ensure workers remain disciplined by scarcity?

Debt, credit, and the punishment of survival

Pressley has also pursued credit-report reforms and student debt relief, which she frames as both economic and racial justice. One reason these issues resonate particularly for Black women is structural: when wages are lower and wealth is thinner, credit becomes a substitute for a living wage. But credit is not neutral. It is priced by risk, and risk is often socially assigned.

Her earlier municipal work limiting the use of credit in hiring anticipated this. The policy logic is not difficult to reconstruct: if the economy pushes Black women into debt and then uses debt as a reason to deny jobs, it becomes a closed circuit.

Nationally, the Washington Post’s coverage of the student loan payment pause emphasized how Black women, who carry a disproportionate share of the student debt burden, stood to gain significantly from the moratorium. Ebony has also covered Pressley’s advocacy around extending student loan relief. The details of federal student loan policy can be tedious; Pressley’s approach is to make it visceral: debt is not simply a number, it is a constraint on family formation, housing stability, entrepreneurship, and even safety—because it reduces options.

In Pressley’s telling, the point is not simply to relieve individual borrowers. It is to break the habit of financing mobility through predatory structures.

Housing stability and the economics of dignity

Housing is another arena where Pressley’s “champion of women” throughline becomes concrete. Women—particularly Black women—are often the household managers and the ones who absorb the administrative violence of instability: negotiating with landlords, juggling utilities, stretching groceries, keeping children anchored while addresses change.

In late 2025, Pressley’s office announced committee progress on bills related to eviction protections and helping families build financial independence, including measures like an eviction helpline and reforms tied to HUD’s Family Self-Sufficiency Program. Even without endorsing every detail as final law, the direction is consistent: reduce the friction costs that fall disproportionately on women and create pathways from precarious subsidy to durable stability.

The care economy, maternal health, and the cost of being a mother

Pressley’s emphasis on maternal health is not a separate “women’s health” concern; it is an economic equality strategy. Maternal mortality and morbidity have direct implications for women’s lifetime earnings, family stability, and generational wealth—and Black women face disproportionate risks in maternal health outcomes.

In 2024, Pressley introduced legislation with bipartisan and bicameral partnerships aimed at expanding access to coordinated maternity care for low-income women on Medicaid, through what her office called the HEALTH for MOM Act. The underlying legislative text for the related 2025 bill on Congress.gov describes a structure that would allow states to provide coordinated care through “pregnancy medical homes” for high-risk pregnant women. She has also worked on maternal health disparities through proposals like the MOMMIES Act, described in Senator Cory Booker’s release as aimed at improving maternal health outcomes and closing disparities affecting Black, Indigenous, and other communities of color.

This is Pressley translating “champion of women” into the kind of policy that changes whether a pregnancy becomes a medical crisis, whether postpartum care is available, whether a woman can return to work safely, and whether a child begins life with stability.

When Black women lose jobs, everyone is being told who counts

In late 2025, BET reported on a Pressley-convened roundtable sounding alarm about job losses among Black women, with the framing that policy retreats and labor volatility are pushing Black women out of work. Even when the exact economic cycle shifts, the political meaning remains: Black women’s job security is often treated as expendable, even as their labor is treated as essential.

Pressley’s broader argument is that this is not merely unfair; it is economically irrational. If Black women are concentrated in education, healthcare, housing, and service work, their displacement is not a niche problem. It is a forecast of institutional failure.

The body as battleground: Visibility, hair, and the costs of representation

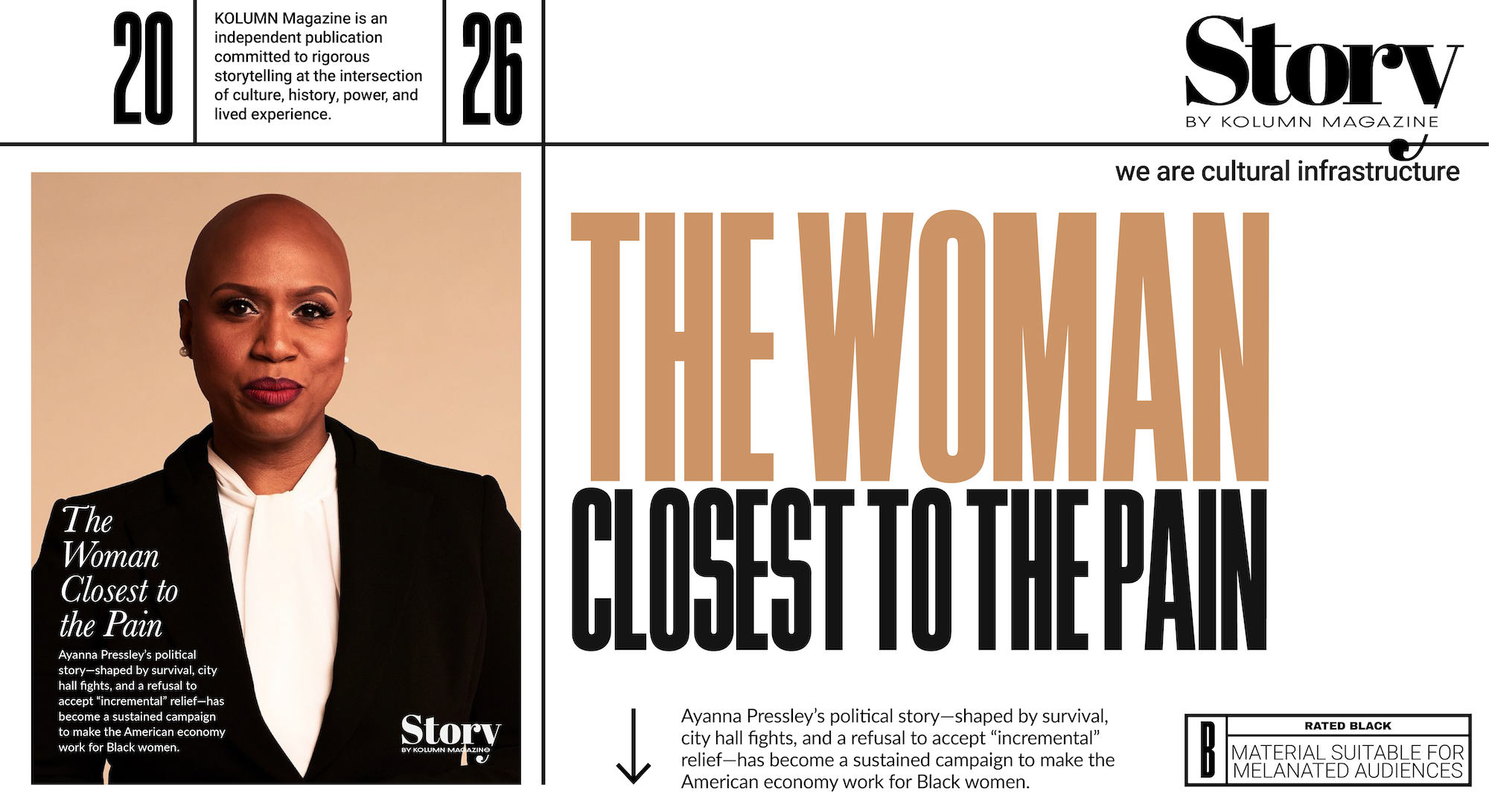

In 2020, Pressley publicly revealed that she had alopecia, an autoimmune condition that caused her hair loss, and spoke about the emotional weight of carrying that diagnosis in public life. The moment became cultural news because Pressley’s hair—often styled in signature twists—had been part of her visual identity, and because Black women’s hair is rarely allowed to be just hair. It is read as professionalism, politics, respectability, rebellion.

The Root published an in-depth interview that treated the disclosure not as celebrity vulnerability but as a political act, and Time reported on her decision to speak publicly as an act of self-agency and transparency, particularly for women of color who saw themselves in her.

KOLUMN Magazine, in a later reflection that referenced Pressley’s alopecia disclosure, framed the moment as an example of a broader reality: Black women’s appearance in public life is often treated as ideological material that others feel entitled to seize.

This is not a side story. It is central to Pressley’s project of being a champion of women because it highlights a quiet tax that women in politics—especially Black women—pay simply to exist in public: they must justify their bodies, manage other people’s projections, and still produce policy outcomes at a higher standard than peers who are never asked to represent an entire demographic.

When Pressley says, in a Root interview, that her very existence can be “disruptive,” she is not performing defiance. She is describing the structural fact that Black women in power challenge norms that were built without them.

Building coalitions without shrinking the ask

Pressley’s political identity is often narrated through the “Squad” frame, but her actual method is coalition-building that tries to keep the moral stakes high without abandoning legislative mechanics.

She has served on committees including Financial Services and Oversight, spaces where economic rules are written and where corruption and institutional failures are investigated. Oversight is not always glamorous, but for Pressley it is aligned with her core thesis: if systems are harming people, the public deserves transparency about who benefits and who blocks repair.

Her interaction with Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington offers a telling example. CREW’s record notes that Pressley submitted CREW’s petition to the congressional record during a 2019 hearing about Hatch Act violations—an act that is both symbolic and procedural, using oversight process to amplify an ethics watchdog’s work. In Pressley’s political worldview, ethics enforcement is not separate from economic equality. Corruption and impunity are part of the machine that keeps wealth and power insulated.

Even in moments when Pressley is framed as an ideologue, her stated argument is often pragmatic. The Washington Post opinion profile described her as trying to build “a very big Squad”—a broader movement that can push the party and the country toward policies that change daily life—and quoted her making a case that persuasion comes from impact.

The premise is consistent: Black women have been asked for generations to accept partial relief and perform gratitude. Pressley is trying to build a politics in which Black women are not the base that is mobilized and then ignored, but the constituency whose outcomes become the definition of success.

Equal Rights Amendment advocacy and the insistence on permanence

One of Pressley’s recurring arguments is that rights that can be reversed are not rights; they are permissions. That is part of why she has engaged the Equal Rights Amendment fight, including public speeches commemorating Black women’s contributions to that movement and involvement in launching a congressional caucus tied to the ERA.

ERA advocacy can sound abstract in an era of urgent economic crisis. Pressley’s framing suggests it is not abstract at all: constitutional and legal scaffolding shapes how vulnerable people can claim protection in the first place. For Black women, whose labor and bodies have historically been exploited under law, permanence is not symbolic. It is security.

Critiques, tensions, and the high standard applied to Black women in power

A credible account of Pressley’s career must acknowledge the criticisms and the political tensions around her.

Some critics argue that the “Squad” label simplifies complex ideologies and that Pressley’s politics are less radical than the brand suggests. A Guardian column, for example, argued against lumping Pressley into a simplistic outsider narrative and emphasized her institutional experience and political positioning.

Others critique Pressley from the opposite direction: that structural ambitions like job guarantees and sweeping debt relief are politically difficult, and that pressuring the party risks backlash or gridlock. Pressley’s counterargument is that gridlock already exists for the people living the consequences. If legislation stalls, people still lose jobs, lose housing, lose healthcare, and lose time.

She has also faced the reality that visibility attracts threat. Biographical accounts and reporting have noted that members of the Squad received intense harassment and threats, particularly during periods when they became targets of national political attacks. The relevance here is not sympathy; it is analysis. When Black women in power are targeted, it functions as deterrence: a warning to future candidates that the cost of visibility may be personal danger.

Pressley’s response has generally been to insist that intimidation will not set the agenda—and to return, again, to outcomes. She treats the attacks as evidence that the work matters.

What Pressley’s story suggests about the economics of Black womanhood

There is a temptation in political storytelling to make the protagonist’s arc feel inevitable. Pressley’s story is not inevitable. It is a chain of choices made inside constraints: leaving school to work, entering politics through staff roles, daring an incumbent, choosing to tell the truth about survival, and trying to legislate at a scale that matches the problems.

But there is a coherence to her project that becomes clearer the longer you track it. Pressley is building a definition of economic equality that goes beyond wages, and she is using Black women’s experience as the diagnostic tool.

If a Black woman can work full time and still be one emergency away from collapse, the labor market is not working. If a Black woman can do everything “right” and still be trapped by debt, the mobility narrative is a lie. If a Black woman can be pregnant and face heightened risk of harm, healthcare is not delivering care. If a Black woman can be evicted quickly with little support, housing policy is designed for landlords, not families. If a Black woman must publicly justify her hair, her body, her trauma, simply to be heard, then representation without structural change becomes another form of extraction.

Pressley’s insistence on being a champion of women is, at bottom, an insistence on replacing extraction with investment.

“Closest to the pain” as a governing standard

Pressley often returns to the idea that the people closest to the pain should be closest to the power. Taken literally, it is a theory of representation. Taken practically, it is a theory of policy design: the people who live the consequences of a system understand its failure modes better than those insulated from them.

In a country that routinely celebrates Black women’s endurance while underpaying their labor, that theory is an escalation. It asks for more than acknowledgment. It asks for redistribution of security.

Pressley’s political fight for the economic equality of Black women is not a single bill or a single speech. It is the cumulative work of trying to make the economy answer a different question than it usually does. Not “how fast can it grow,” or “how cheaply can it run,” but: who gets to live with dignity?

That is a women’s question. Pressley’s wager is that it is also the country’s most important economic question.