KOLUMN Magazine

A time-based telling that does not merely reconstruct what happened, but clarifies what was at stake in each hour.

A time-based telling that does not merely reconstruct what happened, but clarifies what was at stake in each hour.

By KOLUMN Magazine

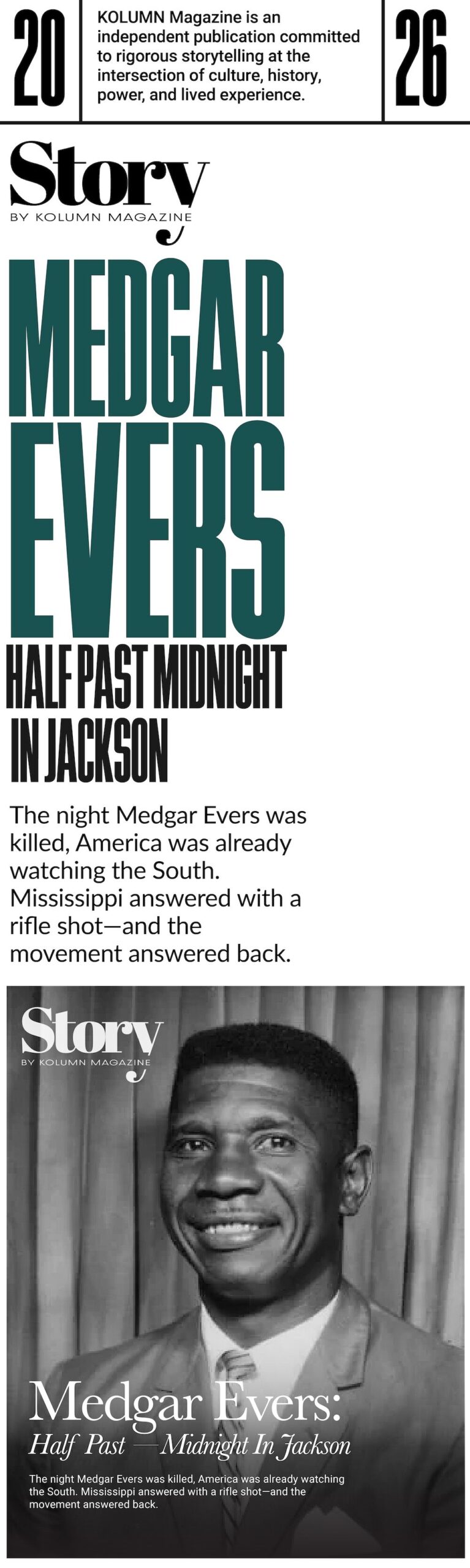

The most important detail about the assassination of Medgar Evers is not the rifle, though the rifle matters. It is not the name of the killer, though the killer’s name becomes, over time, an index of institutional refusal. The most important detail is the sequence: a nation addressed at prime time about civil rights as a “moral issue,” a family still awake in a modest Jackson house, a man coming home from organizing, and then—about half past midnight—the crack of a shot that made the local terror of Mississippi suddenly legible to the rest of America.

June 11, 1963, had already been a day of confrontation in the Deep South. In Alabama, federal authority was forcing open a university door that segregationists tried to hold shut. That evening, President John F. Kennedy went on television to speak to the country about civil rights and conscience, framing discrimination not merely as a political headache but as a moral crisis that demanded federal action. The address was scheduled for 8:00 p.m. and came at a moment when protests had been spreading and intensifying across the South.

In Jackson, Mississippi, Medgar Evers—Mississippi’s NAACP field secretary, a man who spent his days turning outrage into plans—watched the speech with the people he loved most. The FBI’s historical account of the case notes that Evers’s wife and children were still awake after watching Kennedy’s address when the shot rang out. It is a small domestic image—family gathered, a television on, the hour growing late—that makes the violence feel even more intimate.

To understand why that intimacy mattered, you have to remember what the civil-rights movement looked like in mid-1963: not a single march or a single charismatic leader, but a grinding network of meetings, legal strategizing, voter-registration efforts, and economic pressure campaigns—work that required people like Evers, whose leadership was often less visible than it was indispensable. In Mississippi, the movement’s day-to-day mechanics were punished with a ferocity that the rest of the country sometimes treated as rumor until a death made it undeniable.

This is a story told best as a clock.

8:00 p.m.: A president speaks to a country still arguing with itself

At 8:00 p.m. on June 11, Kennedy went live on national television. In the Kennedy Library’s transcript and contextual framing, the address is described as a pivotal moment, delivered after the integration of the University of Alabama earlier that day and during a spring in which civil-rights protests spread across the South. Kennedy spoke directly about the indignities Black Americans faced—unable to eat in public restaurants, vote for officials who represented them, or access equal public education—and asked Americans to imagine themselves in that place.

The power of the speech was amplified by how late it came: almost two and a half years into Kennedy’s presidency, after Birmingham and after a parade of images and stories that made “patience and delay” sound less like prudence and more like complicity. The transcript underscores that the speech was drafted quickly, in only a few hours, and yet it carried the weight of a presidency trying, belatedly, to meet the movement’s urgency with federal language.

In Mississippi, federal language had always been distant. What mattered there was local enforcement—local judges, local juries, local police, local employers. If those institutions aligned against you, constitutional promises did not vanish, but they became difficult to cash.

Medgar Evers knew this better than most. For years he had functioned as a translator between national ideals and local reality—taking what the Supreme Court, the Justice Department, and the national press said should be true, and trying to make it true on a particular street, in a particular courthouse, in a particular county where white supremacy operated not only as belief but as system.

The bitter irony is that Kennedy’s words, spoken to the nation, were received in Mississippi as provocation. The speech did not create the violence that followed it, but it sharpened the contrast that violence depended on: America’s claim that it was changing versus Mississippi’s insistence that change would be punished.

Late evening: Organizing, again

As the night progressed, Evers did what he did nearly every day: he worked. The FBI account states that he had just come home after a meeting of the NAACP.

This is where the movement’s less cinematic reality comes into view. Meetings are not dramatic in the way marches are. Meetings are how a movement becomes durable: who will call whom, what materials will be printed, where the next gathering will happen, how to keep people safe, how to keep the pressure steady enough to matter. In Mississippi, even that kind of work carried a special risk, because organizing itself was treated as an act of subversion.

Other sources fill in details about what Evers was carrying that night: shirts with the words “Jim Crow Must Go.” The National Park Service’s history of the assassination notes that Myrlie Evers found her husband collapsed and bleeding, clutching t-shirts he had carried from the car, and specifies the slogan. The NAACP’s own historical page also references those shirts and the fact that Evers was shot in the back after pulling into his driveway.

The shirts matter because they underscore what Evers was doing: building visible, repeatable symbols that could unify people across fear. A slogan on cotton is not, by itself, a revolution. But it is the kind of thing a revolution uses—portable conviction, worn on the body, a signal that someone is not alone.

Evers was, by then, a known enemy to segregationists. His work had included voter-registration drives, boycotts, and efforts to challenge segregation in Mississippi’s institutions. The NAACP notes that multiple attempts had been made on his life before June 1963.

Inside the Evers household, preparation had become a form of parenting. The National Park Service account states that the children responded that night as they had practiced—dropping to the ground and moving to the bathroom, with the older children helping three-year-old James into the tub for safety.

That detail is among the most devastating in the record: the family had rehearsed the possibility of assassination as if it were a fire drill.

About half past midnight: The shot

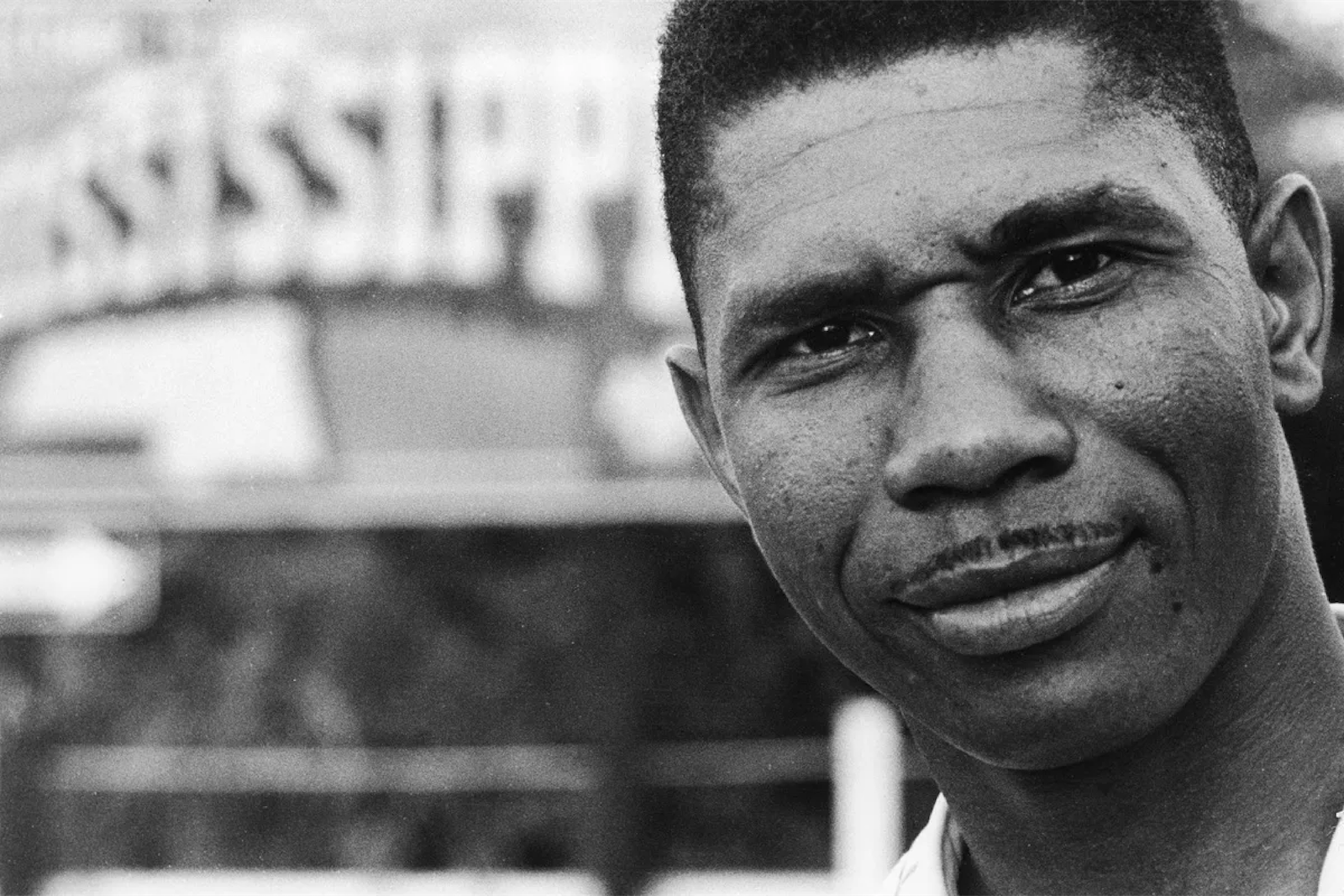

“About half past midnight,” the FBI history states, “a shot rang out.” It was June 12, 1963, in a suburban neighborhood of Jackson. Evers had just returned home. As he began walking toward the house, the bullet struck him in the back. He staggered to the steps and collapsed.

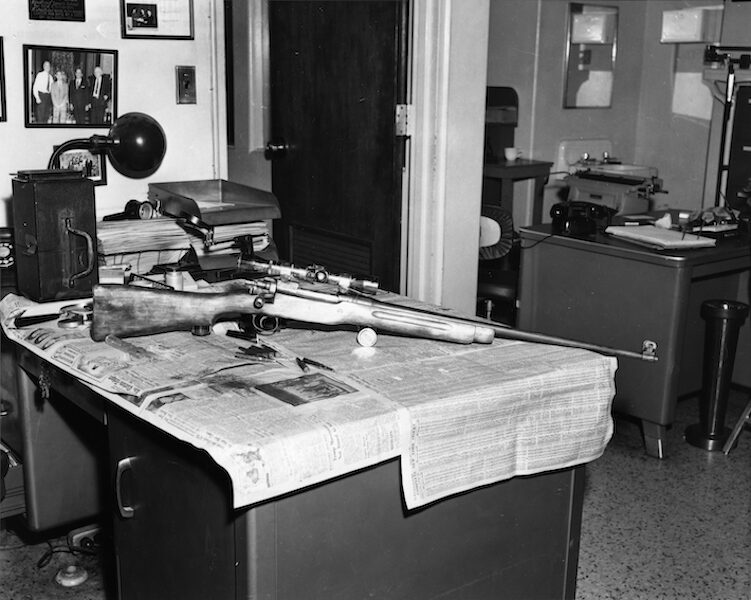

The FBI account adds another scene across the street: a man on a lightly wooded hill jumping up in pain because the recoil of the Enfield rifle drove the scope into his eye, bruising him; the shooter dropped the weapon and fled.

The most chilling thing about assassination is its blend of planning and banality. Somebody had to choose a place with a clear line of sight. Somebody had to wait. Somebody had to decide that a man walking up to his own house was a permissible target. What we call “political violence” in later textbooks arrives in the moment as a single bodily shock: a family hearing a sound, a body falling, blood on a carport floor.

Myrlie Evers rushed out. The NPS account places her stepping into the carport and finding her husband collapsed and bleeding, still clutching the shirts. Neighbors and police arrived within minutes. Rather than waiting for an ambulance, Evers was loaded into a station wagon and rushed to the hospital with a police escort.

The FBI account emphasizes the immediacy too—family, neighbors, police—while noting that Evers died within the hour.

For the movement, the “within the hour” is both literal and symbolic. Within an hour, Mississippi had done what it had threatened to do: punish an organizer with death. Within an hour, a national television address about moral urgency had acquired a counterpoint—proof that moral urgency was not an abstraction.

The hospital: Segregation’s last word, nearly

Evers’s final passage went through an institution that, in Mississippi, was also a border checkpoint: medical care. The NPS account states that he died at University Hospital from trauma and blood loss.

Contemporary retellings and biographical accounts add a further layer: the hospital was “open to whites only” and Evers was initially refused admission—an encounter that encapsulates Jim Crow’s totality, the way segregation sought to govern not just schools and voting booths, but the very right to live through injury. One biographical entry on Myrlie Evers-Williams notes that officials broke the hospital’s color barrier when they realized who he was, but too late to save him, describing his death as occurring roughly 50 minutes after the shooting.

What can be said with confidence, grounded in the NPS account and other credible histories, is that Evers died that night at the hospital, and that the events surrounding his care became part of the story Americans told themselves about what segregation meant: it was not merely separation; it was a hierarchy enforced at the edge of mortality.

That same year, as the Veterans of the Civil Rights Movement timeline documents, segregated health care across the South was a major civil-rights issue—hospitals refusing Black patients, inadequate facilities, and systematic denial of medical privileges to Black doctors, even in tax-funded institutions. Evers’s death did not occur in a vacuum. It occurred inside a regional system that treated Black suffering as manageable and Black survival as negotiable.

The immediate investigation: Evidence on the ground

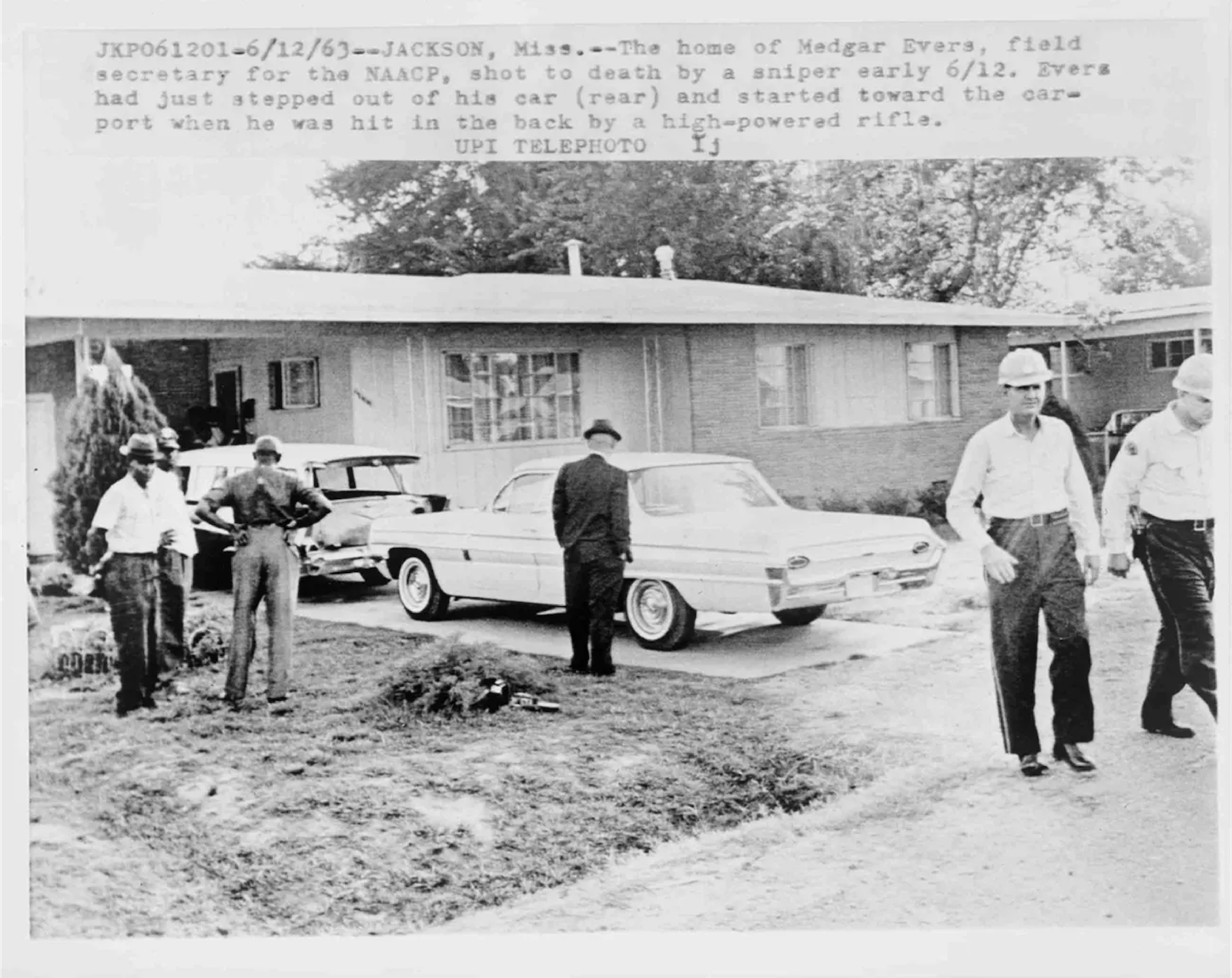

Assassinations produce myth quickly. But this case also produced evidence quickly. The FBI history states that local police found the rifle and determined it had been recently fired, and that a fingerprint recovered from the scope was submitted to the FBI. The Bureau connected the print to Byron De La Beckwith based on similarity to military service fingerprints; Beckwith was arrested several days later.

The same FBI account notes the accumulation of indicators: motive, fingerprint evidence, an injury around the eye consistent with scope recoil, and evidence of planning. It also notes that Beckwith had been asking around about the location of Evers’s home prior to the shooting.

Here is the first point where the story of the assassination merges with the larger story of the movement: Mississippi could not plausibly claim ignorance. The evidence existed. The issue was never simply “who did it?” but “what would the state do about it?”

The morning after: News, grief, and the nation’s attention

By daylight, Evers’s death had to be processed by at least three publics: Black Mississippians who had known the risk intimately, white Mississippians who often treated that risk as a tool, and a broader American audience that was still absorbing Kennedy’s language from the night before.

The Atlantic, in a personal reflection published decades later, captures what many Americans experienced: the word “assassination” applied to a Black activist in a way that made the movement’s danger newly explicit to people who had previously understood violence as possibility but not as inevitability. The essay emphasizes the midnight return from an NAACP event and the shot in the back as he approached his home.

That shift in perception mattered. In many parts of the country, the civil-rights movement was still framed as a struggle for “social change” that might be negotiated gradually. An assassination is not gradual. It is punctuation.

Jackson reacts: Protest meets policing

The anger that followed Evers’s killing was not confined to private grief. It spilled into streets and churches. TIME’s later recollection of 1963 coverage notes that protests in Mississippi after Evers’s murder were met with arrests and violence by police, describing silent walks, paddy wagons, beatings, and young people carrying American flags on Flag Day who were arrested anyway.

This response is crucial to understanding the state of the movement that day: Mississippi’s authorities treated even symbolic protest as a threat to be suppressed. It was a form of messaging as clear as the assassin’s bullet—an insistence that public space belonged to the existing order.

The civil-rights movement’s strategy often depended on revealing exactly this pattern: peaceful action met with disproportionate force, a contrast that could pry open national opinion. Evers’s assassination, followed by harsh policing of protests, created a condensed moral tableau. It did not require complex explanation. A man had been killed for organizing; people who protested the killing were punished. The system, in other words, was revealing itself.

The national movement context: Why June 1963 felt like a hinge

To narrate June 12, 1963, honestly, you have to widen the lens beyond Jackson. Kennedy’s speech came amid a season of escalating confrontation—Birmingham’s campaigns, the mobilization of youth, and the intensifying demands for federal civil-rights action. The Kennedy Library transcript explicitly situates the address within a spring when protests spread “in size and intensity across the South.”

In Mississippi, organizing was entering a new phase as well. SNCC’s account of Evers’s murder frames it alongside the expansion of voter registration efforts into the Delta and the increase in violence against movement workers, noting the role of Citizens’ Councils and local police in terrorizing Black communities fighting for power. (The SNCC page contains an apparent date typo elsewhere, but its description of the conditions and Evers’s role aligns with better-established histories.)

This is the environment Evers moved through that day: a region where national attention was growing but local brutality remained confident.

Evers also occupied a particular place in the movement’s ecosystem. He was connected to NAACP legal strategies and, as Stanford’s King Institute biography notes, maintained contact with Martin Luther King Jr. and had interest in direct action methods, reflecting the period’s cross-pollination between litigation-oriented organizations and mass-mobilization tactics.

In other words, Evers’s assassination was not just the loss of a single leader; it was the removal—by force—of a connective node in the movement’s network.

The funeral and the optics of mourning

When the movement loses a leader, mourning becomes political. Photographs from Evers’s funeral, preserved by LIFE, show the density of grief and the public character of it: mourners gathered, the casket, the solemn choreography of a community forced into ritual by violence.

Evers’s burial at Arlington National Cemetery, with military honors, was another layer of symbolism: a man who had served the United States in war, killed at home for insisting the country treat Black citizens as equal. That symbolism became part of the moral argument the movement was already making—America’s democratic claims were undercut by the violence required to maintain segregation.

The trials: When evidence meets an all-white jury

The case against Byron De La Beckwith was not, on paper, a mystery. According to the FBI, the fingerprint evidence, the rifle, the injury around his eye, and the motive all pointed strongly in his direction.

Yet in the 1960s, evidence was filtered through Mississippi’s judicial reality. The FBI history notes that prosecutors presented a strong case in two separate trials, with police, FBI experts, and others testifying—but both trials ended without verdicts because all-white juries deadlocked. Beckwith went free.

This is where the assassination story becomes a broader indictment of Jim Crow’s legal architecture. The system did not only allow violence; it managed the consequences of violence so that white perpetrators were often protected. A hung jury can be framed as uncertainty. In the context of a racialized court system, it functioned as policy.

The Root’s reporting on Evers’s legacy—written in the context of later commemorations—states plainly that two all-white juries deadlocked and that Beckwith was convicted only in 1994, thirty years later.

Decades later: Reopening the case and the meaning of delayed justice

By the early 1990s, the FBI history notes, “the time was ripe” to revisit the case. Myrlie Evers asked local prosecutors to reopen the investigation and search for other evidence, and the FBI again provided assistance.

In 1994, Beckwith was convicted. The fact of the conviction matters, but so does the timing. The conviction did not simply reflect legal diligence. It reflected a changed political climate, a Mississippi and an America no longer able to absorb the assassination of a civil-rights leader as background noise.

Beckwith appealed the verdict, and the Mississippi Supreme Court upheld the conviction in 1997. The primary legal record of that decision is publicly accessible through case repositories.

What the legal arc reveals is not only that justice can be delayed, but that delay is itself a kind of outcome—years in which the state effectively told Black citizens that even the most prominent murder could be left unresolved. The eventual conviction was therefore not only punishment; it was a revision of public permission.

The house as evidence: A bullet hole that refuses to close

Long after the trials, the Evers home remains a material document. The Washington Post’s 2023 reporting describes Myrlie Evers-Williams sitting in the family’s former home near a bullet hole still visible in the wall from June 12, 1963, underscoring how physical remnants become part of historical memory. The same report notes that the home is now the Medgar and Myrlie Evers Home National Monument, placing the site under National Park Service stewardship.

The NPS account makes clear why the site matters: it preserves the domestic dimension of political violence—the carport, the practiced family response, the shirts in Evers’s hands—details that resist abstraction.

The house also functions as an answer to a question the assassination forces: What, exactly, was the cost of organizing? The bullet hole is a kind of ledger entry.

What the assassination changed—and what it exposed

In the most direct sense, Evers’s assassination removed a critical leader at a critical time. In a deeper sense, it intensified the movement’s clarity about what it faced.

The NPS notes that the nation was shocked and that Evers’s murder “galvanized the civil rights movement and heightened public awareness,” framing his martyrdom as a catalyst for the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which outlawed segregation in private businesses.

The Library of Congress blog similarly emphasizes that Evers became more famous nationally in death than in life and that his assassination, alongside Kennedy’s speech, helped spur action on civil-rights legislation, noting that the Civil Rights Act was signed the following year.

Even when such causal lines are drawn carefully—as part of a broader convergence of events rather than a single trigger—the interpretive point stands: Evers’s death compressed the nation’s attention. It became harder to argue, after a driveway assassination, that the issue was merely social etiquette or regional custom. The question became whether the United States would allow political murder to function as segregation’s enforcement mechanism.

The Atlantic’s 2022 piece frames the moment similarly, arguing that the killing “changed the movement forever” by forcing a recognition that could no longer be deferred.

The movement after midnight: The long echo

Assassination stories often end with the shot. But in the movement’s chronology, the shot was a beginning.

After Evers, the civil-rights movement entered an even more intense phase: the March on Washington later that summer, the legislative battles that followed, and, in Mississippi specifically, the continuing struggle over voter registration and the violence that accompanied it. Myrlie Evers would become an important national figure and a steward of her husband’s legacy, but it is worth emphasizing the human fact before the political one: she lived for decades with the memory of that practiced family drill becoming real.

That persistence—personal and political—helps explain why Evers remains central to the story of 1963. The assassination was not only a crime; it was a message. And the movement’s response—organize, remember, prosecute, commemorate, legislate—was a refusal to accept the message as final.

The Root, in its anniversary remembrance, quotes the line often attributed to Evers—“You can kill a man, but you can’t kill an idea”—and frames the present as another era of political stakes and vulnerability, tying memory to ongoing civic responsibility.

That is the final function of a time-based telling: it does not merely reconstruct what happened, but clarifies what was at stake in each hour.

The sequence that still speaks

If you reconstruct the night with discipline—8:00 p.m., a president speaking; late evening, an organizer meeting; about half past midnight, the shot; minutes later, neighbors and police; a rushed trip to a segregated hospital; within the hour, death—you end up with something more than narrative. You end up with a diagnosis of American democracy in 1963: federal aspiration confronted by local impunity, a moral appeal answered by a rifle, and a family forced to rehearse survival as routine.

The FBI’s account is blunt about the moment the shot rang out. The NPS is blunt about what the children did next. The Kennedy Library transcript is blunt about what the president asked Americans to imagine. Put them together and the night becomes what it has always been: a hinge between what the country said it believed and what it was willing to allow.