KOLUMN Magazine

Brown’s genius was not only that she could fly, but that she could build the conditions under which others could fly.

Brown’s genius was not only that she could fly, but that she could build the conditions under which others could fly.

By KOLUMN Magazine

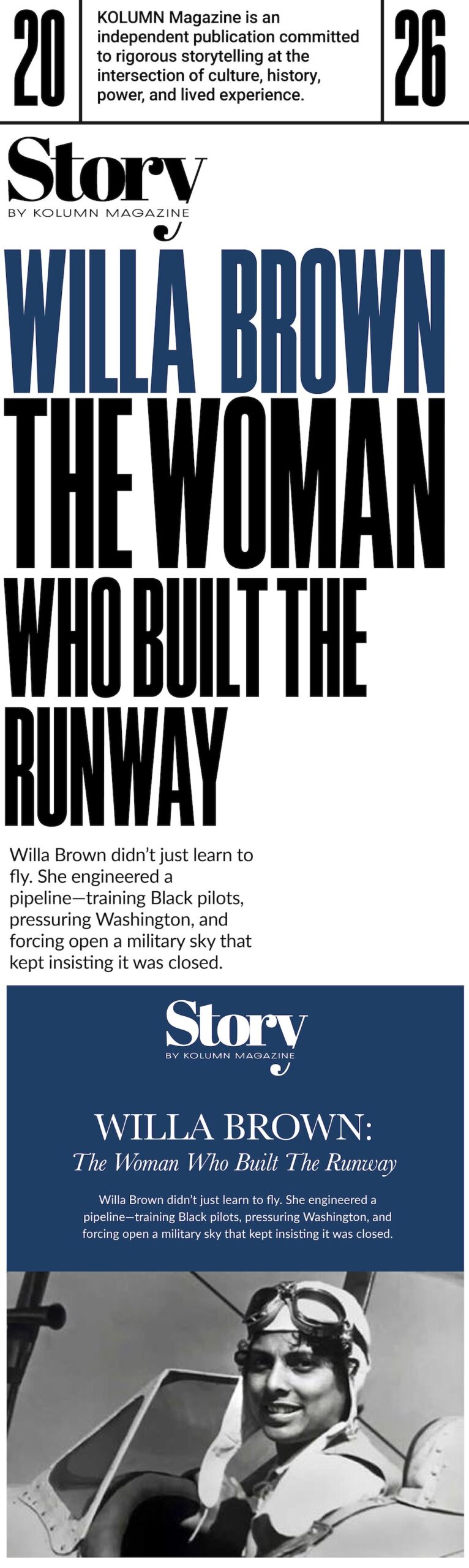

There are lives that read like a series of firsts—tidy, triumphant, and easily reduced to a timeline. Willa Beatrice Brown’s life refuses that kind of packaging. Yes, she was the first African American woman to earn a pilot’s license in the United States, a distinction generally dated to 1938. She went on to become the first African American officer in the Civil Air Patrol and is widely credited as the first African American woman to run for Congress, mounting campaigns in the mid-20th century that were as much a referendum on exclusion as they were bids for office.

But Brown’s most consequential work is harder to summarize than a list of accolades. Her story sits at the intersection of aviation and civil rights—two arenas that, in the first half of the 20th century, were obsessed with control: who could move freely, who could claim public space, who could be certified as competent, who could wear a uniform, who could be trusted with machinery, and who could represent the nation. Brown did not merely enter those controlled spaces. She tried to redesign them.

In archival accounts and museum histories, she appears again and again not only as an aviator but as an organizer and systems-builder: a woman who treated flight training as infrastructure, who understood that an individual license mattered less than a pipeline capable of producing hundreds of credentialed Black pilots, mechanics, and aviation leaders.

Her achievements are sometimes described with a kind of astonishment—commercial pilot, mechanic, educator, activist—yet the astonishment can obscure the underlying logic. Brown’s life makes sense when you recognize how she moved through a world that demanded proof at every step. She gathered credentials the way others gathered weapons, not for symbolism but for leverage. When the gatekeepers said Black Americans lacked the aptitude to fly, she became a pilot and a mechanic. When bureaucrats said there were no qualified applicants, she built a school. When institutions claimed neutrality while practicing exclusion, she lobbied, organized, and ran for office.

It is also a life shaped by constraints—economic, racial, gendered, political—whose pressures rarely show up in commemorative plaques. To understand Brown’s accomplishments is to grapple with her challenges: the segregated nature of American aviation training, the precariousness of Black institutions during wartime and postwar shifts, the friction of being a Black woman in a field that treated both Blackness and womanhood as disqualifying. The obstacles were not abstract. They were written into airfields, contracts, admission standards, newspaper narratives, party politics, and military doctrine. Brown met them with a mixture of pragmatism and confrontation: she learned the rules, then tried to change them.

From Glasgow to the industrial Midwest, and the long apprenticeship of ambition

Brown was born in Glasgow, Kentucky, in 1906, a fact repeated across biographies, museum profiles, and state historical materials. The date—January 22—is widely used, though even official-seeming summaries sometimes disagree by a day, an inconsistency that underscores how easily Black women’s histories can be flattened or mishandled in the record. What remains consistent is the arc: early life in Kentucky and a move northward, part of the broader Great Migration pattern that reshaped the Black American experience in the early 20th century.

Accounts emphasize education as a throughline. Before she became “Lieutenant Willa Brown,” the aviatrix in photographs standing between airplane propellers, she worked in fields where Black women could plausibly find employment: teaching, clerical work, nursing-related training, and other forms of professional labor that still carried the weight of discrimination. The National Archives’ “Maker of Pilots” narrative notes that she held a variety of jobs to support herself before aviation became her center of gravity.

Those early jobs matter because they framed the way Brown approached aviation. Flying lessons were expensive. Training required time, equipment, and access to an airfield culture that was often hostile or dismissive. Brown entered the world of flight not as a hobbyist of means but as a woman building a second career under constraints. That reality shaped her later insistence on federal programs and contracts—not as handouts but as mechanisms to democratize access in a nation that otherwise stratified opportunity by race and wealth.

By the early-to-mid 1930s, Chicago had become a crucial site for Black aviation. In the popular imagination, Black flight history in the U.S. is often anchored to Bessie Coleman—who traveled to France in the 1920s to obtain an international pilot’s license when American schools refused her—then leaps to Tuskegee in the 1940s. Brown’s story demonstrates what that narrative skip conceals: the local ecosystems, segregated airfields, and community organizers who created the conditions for Tuskegee to become possible.

One recurring detail in Brown’s biographies captures both her resourcefulness and the segregated economy of the airfield. At Chicago’s Harlem Field (often described as racially segregated), Brown ran a lunchroom—an enterprise that brought her into daily contact with pilots, instructors, mechanics, and the flow of aviation work. It was not simply a side job. It was an embedded position in the ecosystem, a way to fund training and build relationships in a world where formal entry points were limited.

In that same period, she pursued aviation instruction and, critically, aviation maintenance. The Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum highlights Brown’s path through both flight and mechanics, noting her private pilot license in 1938 and her later commercial credentials, situating her as a figure who “opened doors for Black pilots.” Her mechanical training is often linked to Curtiss-Wright Aeronautical University, and multiple sources emphasize the significance of her earning an aircraft mechanic’s license in the 1930s—certification that signaled technical competency in an era when racist pseudoscience and military assessments cast doubt on Black aptitude.

This dual competency—pilot and mechanic—was not a curiosity. It was a strategy. In a labor market and professional culture quick to question her legitimacy, Brown accumulated forms of proof. A license meant she could fly. A mechanic’s credential meant she understood the machine. Together, they made it harder for institutions to dismiss her as a novelty.

The first license is a door; The first school is a blueprint

Brown’s “first” is typically phrased in the clean language of milestone: the first African American woman in the United States to earn a private pilot’s license (1938), and soon after, a commercial pilot’s license (commonly dated 1939). The Washington Post, in an obituary for another aviation trailblazer, references Brown as part of the lineage that followed Bessie Coleman, noting Brown as the first African American woman to receive a pilot’s license in the United States.

Yet Brown’s life suggests that the license was never the endpoint. It was a credential to be deployed.

By the late 1930s, Brown’s organizing instincts converged with her aviation training through her partnership with Cornelius Coffey, a leading Black aviator and educator in Chicago’s flight community. The Smithsonian has documented Coffey’s role in Black aviation and includes imagery of Brown within that training milieu at Harlem Airport, underscoring the collaborative nature of the ecosystem she helped build.

Together with Coffey and other partners, Brown helped establish the National Airmen’s Association of America, an organization explicitly committed to increasing the number of Black pilots and pushing for access to military aviation pathways. The U.S. Air Force’s historical news feature frames the organization’s purpose bluntly: to get Black aviation cadets into the U.S. military. Brown served as national secretary and took leadership roles within the Chicago branch—positions that signal her work as a political operator as much as an aviator.

What did it mean to build a Black aviation pipeline in the late 1930s and early 1940s? It meant confronting the fact that aviation, more than many fields, is regulated by credentialing regimes—licenses, ratings, medical standards, instructor certifications—administered by institutions that were not race-neutral in their practice. It also meant raising funds and maintaining equipment in a context where Black entrepreneurs were routinely denied capital, forced into unfavorable terms, or excluded from mainstream business networks. Brown’s challenge was not only to master aviation but to create an institution durable enough to survive those pressures.

That institution became the Coffey School of Aeronautics, often credited as the first private flight training academy owned and operated by African Americans. Brown did not merely teach there; she ran it, promoted it, and used it as a platform to demand federal recognition and resources.

The school’s significance becomes clearest when you trace the federal programs of the era. As the United States prepared for war, aviation training expanded through initiatives such as the Civilian Pilot Training Program (CPTP), a federal effort to build a reserve of trained pilots. Brown lobbied for Black inclusion and for the awarding of CPTP-related training contracts to organizations that could actually train Black students—because access without capacity would have been symbolic at best. The National Archives’ narrative emphasizes Brown’s readiness and leadership in Chicago’s Black aviation community as she pursued those opportunities and advocated for Black flyers.

Her activism was not separate from her role as an educator; it was an extension of it. Training a pilot is a slow, meticulous process. You cannot shortcut competence. Brown’s politics, similarly, were rooted in the insistence that Black Americans already had the capacity and could demonstrate it—if the nation stopped denying access to training, equipment, and formal pathways. Her school functioned as evidence in motion: every student trained, every checkride passed, every mechanic certified became another argument against exclusion.

It is in this context that Brown’s relationship to the Tuskegee Airmen is often invoked. Popular accounts describe her as a teacher of hundreds of future Tuskegee Airmen, and the National WWII Museum positions her as a “maker of pilots” whose students helped populate the pipeline into Black military aviation. While numbers can vary across summaries, the repeated claim across institutional histories is consistent: Brown’s training efforts fed directly into the cohort of Black aviators who would become central to the war effort and to the argument for desegregation.

At the same time, the Coffey School story complicates any simplistic celebration. Some histories note that Coffey opposed the Tuskegee program because it perpetuated segregation even while creating opportunity—an internal tension within Black aviation advocacy that mirrors broader civil rights debates: whether to accept segregated pathways as stepping stones or reject them as legitimization of injustice. Brown’s life suggests she navigated that tension pragmatically, using the options available while continuing to push for structural change.

War, uniforms, and a nation’s reluctance to see Black women as authority

If flight training and advocacy were one axis of Brown’s work, the other was legitimacy—public, institutional, and symbolic. In aviation, legitimacy can be literally uniformed: the right insignia, the right commission, the right title.

Brown became a lieutenant in the Civil Air Patrol (CAP) during World War II, a role that multiple sources frame as historic: she is described as the first African American officer in the CAP. The Civil Air Patrol itself has preserved her legacy through internal materials and cadet program references, underscoring her as a pioneering figure in the organization’s history.

The significance of that commission is easy to understate if you read it as a mere honorary title. In wartime America, uniforms were political. They signaled belonging, authority, and the right to participate in national defense. For a Black woman to hold an officer’s rank in an aviation-adjacent institution challenged deeply held assumptions about who could be trusted with command, with equipment, with responsibility for others. One summary of her CAP role notes that she administered command for large numbers of members—an administrative and leadership function that contradicts any notion that her appointment was symbolic.

Her wartime work also intersected with federal aviation administration. Accounts describe her as a war-training service coordinator connected to civil aeronautics authorities, a role aligned with mobilization and training logistics.

And yet, even as Brown accumulated credentials and responsibilities, the broader military aviation establishment remained resistant to integrating Black Americans fully, and even more resistant to imagining Black women as pilots in any official capacity. Brown’s activism—through the National Airmen’s Association and direct lobbying—targeted those barriers explicitly.

The rhetorical environment she confronted was not subtle. One recurring reference in Brown’s biographies is a 1925 Army War College study that deemed African Americans unfit to fly, a document often cited as emblematic of institutionalized racism in military assessment. Brown’s life work can be understood as an extended rebuttal to that logic—not only through argument but through production: producing trained pilots, producing flight hours, producing demonstrated competence.

This is where Brown’s story challenges the “great individual” framing that often surrounds pioneers. Brown did not simply prove she could fly. She insisted that proving one person could fly was insufficient, because the institutions could always treat her as an exception. Her aim was to make exceptions impossible by making Black aviation presence routine.

The political wager: When the ballot becomes another kind of runway

Brown’s shift into electoral politics is sometimes described as a surprising turn—aviator to candidate—but it aligns with her broader pattern. When one gate remained locked, she looked for another lever.

The National Archives’ exhibit on Brown notes that she is credited as the first African American woman to run for Congress and identifies three runs—in 1946, 1948, and 1950—efforts that ended in defeat but established a precedent of Black women asserting federal political ambitions in an era that rarely welcomed them.

To run for Congress as a Black woman in mid-century Chicago meant confronting multiple overlapping structures: the power of party machines, the racialized boundaries of districts and patronage, the skepticism of donors, and the media’s tendency to frame Black candidates—especially women—as symbolic or fringe. Brown’s campaigns should not be read only in terms of votes won or lost but as public acts of insistence. In aviation, she demanded that Black flyers be treated as potential military assets rather than civic ornaments. In politics, she demanded the right to represent, to legislate, and to be taken seriously as a federal decision-maker.

It is difficult to reconstruct all the campaign specifics from easily accessible public summaries, and major national outlets appear to mention Brown more often as a historical reference point than as a subject of sustained reporting. One of the clearer mainstream references available in open web sources is the Washington Post’s lineage note in an obituary for another aviator, which situates Brown within the broader chronology of Black women’s aviation firsts rather than detailing her campaigns. That scarcity is itself informative: it reflects how a figure can be crucial in shaping an institution and still remain peripheral in national political memory.

What we do have, through archival framing, is the sense that Brown’s political work was not detached from aviation advocacy. Her lobbying for training programs, contracts, and integration placed her in contact with policymakers and bureaucratic processes. Politics—formal and informal—was already part of her life. Running for office was an escalation: a decision to stop only petitioning power and to seek it.

Her defeats do not negate the audacity of the attempt. They reveal the depth of the resistance she faced. Brown was challenging not only the racial order but the gender order of American politics. Even today, a Black woman’s campaign can be treated as an anomaly rather than an expected part of democratic competition. Brown was doing it in the 1940s.

The personal costs behind the public firsts

Pioneers are often flattened into symbols. Brown’s life, viewed more closely, shows the human costs of constant public struggle.

Her biographies note multiple marriages, and while personal relationships are not the primary measure of a life, they can be windows into the pressures that public roles impose. Brown’s professional world demanded constant negotiation of authority in environments that doubted her. Her activism required conflict with powerful institutions. Her work schedule—teaching, running programs, lobbying—left limited room for ease. It is not difficult to imagine how the strain of that life could spill into private domains.

The archival and museum narratives tend to treat Brown’s personal life sparingly, which is typical for women whose public contributions are already under-recognized: historians often focus on “proof of accomplishment” and avoid speculation. That caution is appropriate. What can be said, based on accessible accounts, is that Brown continued working for decades beyond her most famous aviation-era achievements, including teaching in Chicago’s public school system into the later 20th century, a reminder that even historic pioneers frequently relied on stable employment outside the spotlight.

Her postwar years also reflect a broader truth about wartime opportunity: the war expands pathways and then, when the emergency ends, institutions often attempt to shrink again—sometimes snapping shut on those who were only conditionally welcomed. Flight schools close. Contracts end. Public attention shifts. For Black institutions, these shifts could be particularly severe. The Coffey School’s trajectory—rising with wartime demand and later ceasing operations—mirrors the fragility of Black-led enterprises in regulated sectors.

Brown’s life after peak visibility is a testament to endurance. She did not disappear; she persisted. Some accounts note her service on an FAA advisory committee focused on women, suggesting that she continued to shape aviation policy conversations even when she was no longer the headline “first.”

Why Brown’s challenges were structural, not episodic

A common mistake in writing about trailblazers is to treat discrimination as a series of personal affronts—an insult here, a rejection there—rather than as an institutional design. Brown’s story is better understood as a map of structural barriers.

Start with the airfield. Brown trained in Chicago at a time when access to facilities and instruction was racially segregated. Aviation is not a profession you can enter without infrastructure: runways, aircraft, instructors, maintenance, certification. Segregation in aviation therefore functioned as a technology of exclusion, not merely a social practice. It determined who could accumulate flight hours, who could access a mechanic’s workshop, who could get the instructor time required for ratings.

Then consider credentialing. Licenses are administered through authorities and systems. Even if the written rules are nominally neutral, the process can be biased through discretion, access, cost, and gatekeeping. Brown’s relentless pursuit of credentials was a response to that regime.

Next, consider federal contracting. Wartime training programs created funding streams that could either democratize opportunity or reinforce existing inequalities. Brown’s lobbying for CPTP inclusion and for contracts for Black training institutions was a sophisticated recognition that access to money is access to capacity. A training program without funding is a promise without airplanes.

Finally, consider narrative. Who gets remembered? Which achievements become national mythology and which are treated as footnotes? Brown’s relative obscurity in mainstream national coverage, compared with the magnitude of her contributions, is a narrative barrier that shapes public understanding of history and, by extension, policy priorities. When you do not remember that Black women built aviation infrastructure, you are less likely to fund or protect the institutions that might do it again.

The question of recognition: How America honors, and how it forgets

Brown did receive recognition in her lifetime and after. Sources note that she was profiled by Time magazine in 1939, a sign that her achievements broke through the era’s media filters, at least briefly. She has been featured in museum histories and archives exhibits, including the National Archives’ “Maker of Pilots,” which uses her own correspondence and documentation to illustrate her advocacy.

Organizations have also institutionalized her legacy. The Civil Air Patrol references her in educational materials and achievements, framing her as a model of service and leadership. The Smithsonian has published editorial histories explicitly designed to “open doors” in public memory for Black pilots and the educators who trained them, with Brown positioned as central rather than marginal.

State and regional commemorations, too, have carried her story: Kentucky institutions and history organizations have highlighted her as a native daughter who broke national barriers. These commemorations matter, but they also reflect the common pattern of posthumous recognition: the nation often becomes comfortable celebrating a pioneer once the pioneer is no longer demanding change.

Brown died in Chicago in 1992. The distance between her death and the present raises a question that every serious profile of a historical figure must confront: what changed because she lived, and what did not?

What changed: Pipelines, precedents, and the language of possibility

Something material changed because Willa Brown lived: a pipeline was built.

This is not metaphor. Brown’s work helped produce trained Black pilots and mechanics at scale, and that scale mattered in wartime arguments about manpower and national defense. If the U.S. government and military could claim a need for pilots while excluding Black candidates, Brown’s school and advocacy attacked that contradiction.

Tuskegee—however complicated as a segregated institution—became a central symbol in the eventual desegregation of U.S. military aviation and the broader armed forces. Brown’s role as an educator and advocate is repeatedly positioned as part of the chain of events that made Tuskegee feasible and made its success undeniable.

Another change is political precedent. A Black woman running for Congress in the 1940s established a fact that cannot be reversed: it can be done. Precedent is a kind of infrastructure, too. It becomes a reference point for later candidates, a story that expands the imaginative boundaries of who belongs in power. The National Archives’ framing of Brown as the first African American woman to run for Congress is therefore not a trivia fact; it is a marker of democratic expansion achieved through personal risk.

What did not change: The endurance of gatekeeping, and the cost of entry

And yet, the need to retell Brown’s story as rediscovery—“made history,” “opened doors,” “maker of pilots”—suggests how much remains unresolved. Aviation, like many technical fields, still reflects disparities in access, training costs, and representation. The fact that Brown’s name is not widely known outside aviation history circles reveals how easily Black women’s systems-building labor is erased from popular narratives, even when that labor reshaped institutions.

Brown’s life also reminds us that “firsts” can become a trap: they allow institutions to celebrate a singular breakthrough while resisting broader change. Brown tried to avoid that trap by focusing on scale—training many, not just herself. But the cultural tendency to reduce her to a first persists, and it is one reason her political and organizational work deserves equal billing with her flight credentials.

A closing scene: The sound of an engine, the discipline of a plan

It is tempting, in writing about aviators, to end with a flight: the roar of a propeller, the lift of a runway, a solitary figure rising into open sky. Brown’s story suggests a different ending—less romantic, more accurate.

Picture the classroom and the hangar. Picture the paperwork: applications, logs, certification documents, letters to officials, proposals for training programs. Picture the lunchroom at the airfield, the day-to-day hustle that funds lessons. Picture the meetings of an association built to pressure the government, and the campaign work of a congressional run that insists a Black woman can claim federal power.

Brown’s genius was not only that she could fly, but that she could build the conditions under which others could fly—and then argue, relentlessly, that the nation had no legitimate reason to keep them grounded.

If the American story of aviation is often told as a tale of lone heroes and technological daring, Willa Brown offers a corrective: the sky is not only conquered by courage. It is negotiated through institutions. It is granted through credentials. It is funded through policy. It is rationed by race and gender until someone, like Brown, refuses the rationing and gets to work on the machinery beneath the myth.