KOLUMN Magazine

By KOLUMN Magazine

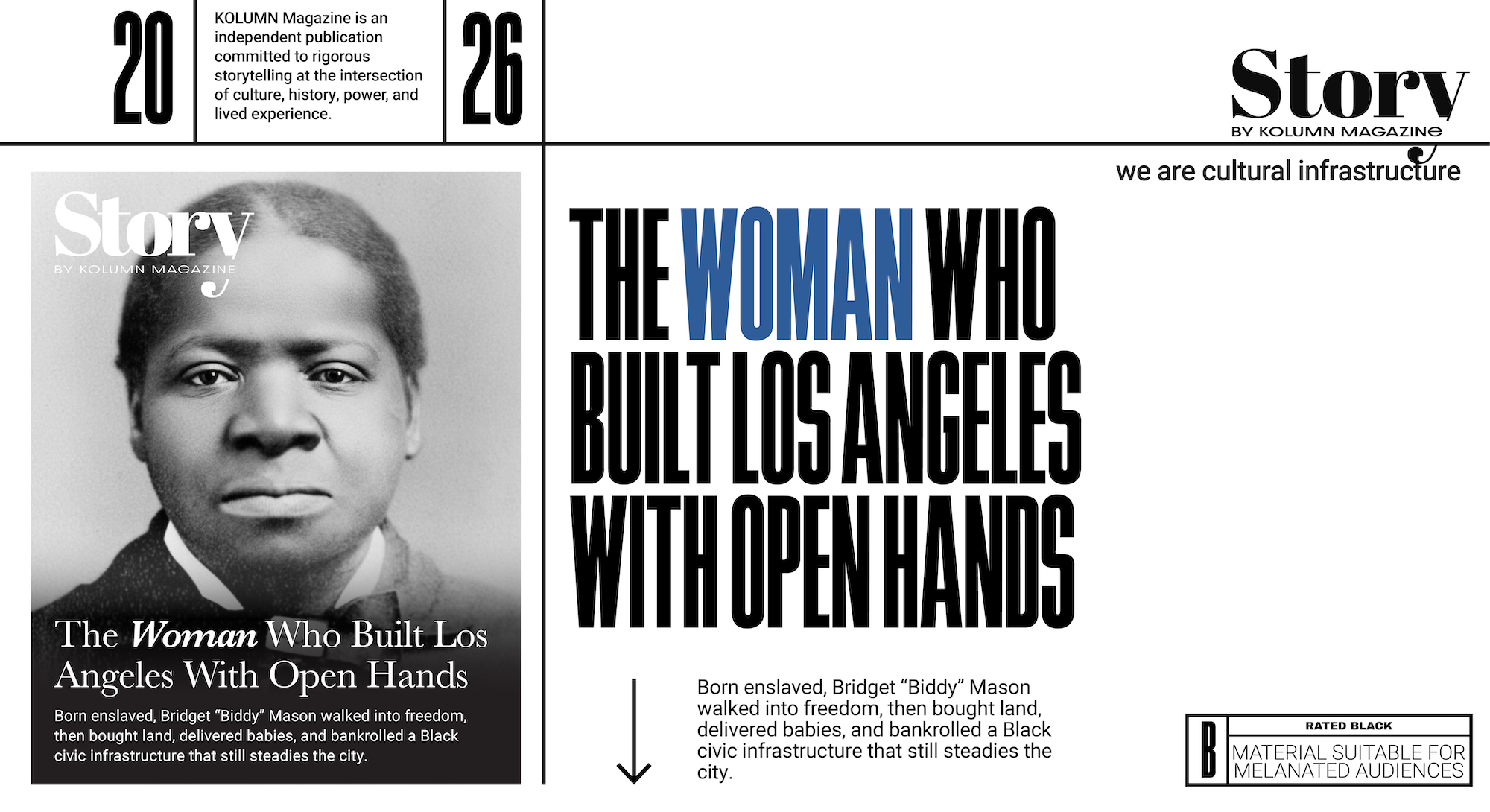

There is a particular kind of Los Angeles legend that the city tells about itself: the myth of a place where reinvention is not just possible but expected, where the future is always under construction, and where the past is something you can outpace if you drive fast enough. Yet some of the most consequential Angelenos did not arrive in the city with a script for self-invention; they arrived under compulsion, without legal personhood, and with no guarantee that freedom—if it could be seized—would be recognized as anything more than a temporary interruption in someone else’s claim. Bridget “Biddy” Mason is among the clearest rebukes to the easy romance of the Western story. Her life, spanning slavery in the South and opportunity in the far West, demonstrates a truth that American mythologies often evade: freedom is not an abstract destination. It is a set of material conditions—legal status, bodily safety, wages, property, shelter, community—that must be created and defended, sometimes one small decision at a time, sometimes in a courtroom where the stakes are nothing less than who counts as human.

Mason’s story is often summarized as a sequence of transformations: enslaved woman becomes free woman; nurse and midwife becomes entrepreneur; a figure forced to the margins becomes a civic pillar. Those transformations are real, and they are remarkable. But they can also obscure the harder insight her life offers. Mason did not simply “overcome.” She practiced a kind of deliberate authorship, converting what she had—knowledge of healing, a talent for saving, an instinct for organizing care—into institutions that outlived her. In the decades after she won her freedom in 1856, she built a life that braided together medicine, real estate, philanthropy, and Black institution-building in early Los Angeles, including her role in founding the city’s first Black church, First A.M.E.

Even the memorial that carries her name in downtown Los Angeles is constructed as a timeline: an 80-plus-foot wall that marks the decades of her life and embeds objects—wagon wheels, herbs, a midwife’s bag—into the public surface of the city. It invites passersby to read her life as a passage of time and, by implication, a passage into modernity. But Mason’s truer passage may be the way she moved from being treated as property to becoming a property owner, and then from being a solitary success story to becoming a conduit through which others could survive. That second transition—success into responsibility—feels especially urgent now, in an era when American public life is again debating what histories can be taught, what kinds of belonging count, and who gets to claim the city’s origin story.

A life that begins in the ledger of slavery

Biddy Mason was born in 1818, enslaved from birth, in the world that slavery built and maintained through paper: bills of sale, plantation inventories, probate records, and the relentless arithmetic of human lives counted as assets. The details of her early years are fragmented, as they are for so many enslaved people whose biographies survive as traces in other people’s documents. What emerges, across historical accounts, is a woman who developed practical expertise—medicine, childcare, livestock care—long before she was legally recognized as someone who could own even her own labor.

Those skills mattered because enslaved life demanded them. Enslaved women were expected to be, simultaneously, agricultural laborers and domestic workers, caretakers and cooks, nurses and midwives—trained not by formal schooling but by necessity, observation, and the intergenerational transfer of knowledge under conditions of coercion. By the time Mason reached adulthood, she had become a capable healer, the kind of person whose competence could sustain other people’s lives even when her own life was treated as disposable.

That paradox would follow her west.

Westward under coercion: The journey that tested California’s “free state” claim

Mason’s path to California ran through a well-known American narrative—the westward migration of the mid-19th century—but with a crucial difference. She did not go as a free settler seeking land and possibility. She went as an enslaved woman, traveling with the household that claimed her, in a movement that illustrates how slavery’s reach extended beyond the plantation South and into the nation’s expansionist ambitions.

Multiple accounts describe Mason being taken west by enslavers connected to a Mormon migration. In broad outline, she traveled in the early 1850s to California, arriving first in the San Bernardino area, at a time when the state’s status as “free” in law did not necessarily translate into freedom in practice for Black people whose bondage was enforced by violence, isolation, and the complicity of local authorities.

This distinction matters. California entered the Union in 1850 as a free state, but freedom in California was often contingent, contested, and unevenly enforced—especially for Black residents. Mason’s story is repeatedly invoked in discussions of California’s relationship to slavery precisely because it demonstrates how the state could be “free” on paper while still being a place where enslavers attempted to hold people in bondage and move them across borders to preserve that control.

In 1856, Mason’s enslavers planned to take her and her children out of California and into Texas, a slave state. Mason understood what that move meant: it would place her beyond the jurisdiction that might recognize her freedom, and it would harden the practical reality of enslavement into something far more difficult to contest. The decision she made—to resist removal and to seek legal protection—was a form of political action at the scale available to her. It was also a gamble. Courts could be hostile, witnesses could be unavailable, and the punishment for defiance could be severe.

She took the risk anyway.

The hearing in Los Angeles: Freedom as a legal event, and a public spectacle

The legal episode at the center of Mason’s life is often referenced as Mason v. Smith, the case in which a California court granted freedom to Mason and her children in 1856. The bare description— “a court granted freedom”—can make the outcome sound inevitable, as if the law simply asserted itself. Historical accounts suggest the opposite: that the hearing was contentious and public, a moment when the small city of Los Angeles watched a Black woman’s fate become a test of whether the state’s “free” status would mean anything in a courtroom.

At the time, Los Angeles was still more pueblo than metropolis. One account describes it as a rough settlement of only a few thousand people, the kind of place where reputations were made quickly and where a courtroom drama could become civic theater. Mason’s case forced residents to confront an issue that many preferred to keep quietly managed: whether enslavers could treat California as a temporary stopover while preparing to transport enslaved people into places where slavery was clearly legal.

Mason’s victory was not only a personal liberation. It was a precedent-setting demonstration that Black people could use the courts to challenge bondage in California, and that local authorities could be compelled to recognize that challenge.

The legal transformation mattered, but it did not end the story. In some ways, it began the harder chapter: what does freedom become, once the state recognizes it?

Choosing a name, choosing a life: The early years of freedom

Freedom is often narrated as a single moment—an order signed, a door opened, a chain removed. For Mason, freedom also required reinvention in the most practical sense. She needed work, housing, and a network. She had children to protect and a future to build in a city that did not offer Black women a clear path to security.

Some accounts emphasize a symbolic act: after emancipation, she chose a last name—Mason—and with it, a public identity that slavery had denied her. It is tempting to romanticize that gesture, but the choice of a surname was not only symbolic. It was a tool. Names are how you sign contracts, claim wages, and acquire property. They are how you become legible to the bureaucracies that regulate economic life.

Mason found work as a nurse and midwife, drawing on expertise developed in slavery and refined in freedom. She became known for delivering babies and caring for the sick, including during disease outbreaks that tested early Los Angeles’s fragile public health infrastructure. Her medical work connected her to influential households, but it also positioned her as something even more consequential: a person trusted across social boundaries in a city where race and gender restricted most forms of authority.

This is a key feature of her life: Mason’s authority did not come from office or title. It came from being needed, from competence under pressure, from the intimate credibility of healing work. And she leveraged that credibility into something many people who knew her did not expect a formerly enslaved Black woman to achieve in the 19th century West: wealth.

The making of a real estate entrepreneur: Land as safety, land as leverage

Mason’s ascent in Los Angeles is inseparable from property. She saved money from her work as a nurse and midwife and invested in real estate at a time when downtown Los Angeles was still developing. This detail is sometimes reduced to a celebratory slogan—“the first Black female property owner,” “a real estate mogul”—but the deeper significance lies in what property meant for a Black woman born into slavery.

In the 19th-century American legal imagination, property was not merely an asset class; it was a measure of personhood. Enslaved people were property; free citizens owned property. To reverse that relationship—to become an owner—was to perform a kind of civic contradiction: the woman once listed in a ledger now writing her own acquisitions into the city’s record of ownership.

The surviving accounts consistently describe Mason as a careful saver and strategic investor. The strategy was not glamorous. It was, in many ways, the opposite of the frontier fantasy. It involved restraint, planning, and an understanding of how cities grow: where foot traffic will increase, where commerce will cluster, where land that seems peripheral will become central. Her property holdings would eventually place her among the more financially secure residents of 19th-century Los Angeles, a rare feat for anyone, and an extraordinary one for a Black woman with her origins.

Yet Mason’s wealth was not simply personal. Over time, it became social infrastructure.

The “open hand”: Philanthropy as a civic practice, not a personality trait

If Mason’s life ended with financial success, she would still be historically notable. But the enduring reverence attached to her name in Los Angeles stems from what she did with that success. Accounts across museums, local histories, and community reporting portray her as a consistent giver—someone who fed the hungry, supported people in crisis, and treated charity as an obligation of freedom.

The phrase most associated with her—“The open hand is blessed”—appears repeatedly in public storytelling about Mason, including commemorations of her legacy. Whether or not every attributed quote can be authenticated with the rigor historians prefer, the persistence of the phrase tells us something about how she was perceived. People remembered not only what she achieved but how she behaved once she achieved it.

In a city still forming its institutions, Mason’s philanthropy functioned as an informal welfare system. When people lined up outside her home seeking help, it was not merely because she was kind; it was because the city had limited mechanisms to assist the poor, the displaced, the newly arrived, or the sick. In that sense, Mason’s generosity was a form of governance—unofficial, personal, but materially impactful.

This framing matters because it avoids a trap common in heroic biographies. When we describe Mason primarily as “charitable,” we risk treating her giving as temperament rather than strategy. But in early Black communities, mutual aid was not sentimental; it was survival. Mason’s open hand was part of a larger Black tradition of building parallel support systems in the face of exclusion, discrimination, and limited public services.

Founding First A.M.E.: Building a Black public sphere in the city’s living rooms

One of Mason’s most consequential achievements was her role in founding the First African Methodist Episcopal Church of Los Angeles in 1872, widely described as the city’s oldest African American congregation and, in its early form, the first Black church in Los Angeles. The organizing meetings, according to accounts preserved by local historical organizations, took place in her home—her Spring Street living room becoming the birthplace of a key Black institution.

It is difficult to overstate what a church meant in a 19th-century Black community. It was spiritual, yes, but it was also civic: a place for schooling, organizing, leadership development, mutual aid, and the articulation of community interests in a society that often refused to represent them. When Mason helped found and finance First A.M.E., she was not simply supporting religious worship; she was investing in the infrastructure of Black public life.

Here again, her real estate and her philanthropy converge. Church-building required land, money, and trusted leadership. Mason’s wealth provided resources; her reputation provided legitimacy; her home provided space when public space was limited. In a city where Black residents were numerically small and politically constrained, the creation of a stable institution mattered as much as individual success.

A Black woman healer in an expanding city: Medicine, authority, and the politics of care

Mason’s medical work is sometimes described as domestic labor in a more dignified form, but that framing misses the expertise involved. Midwifery in the 19th century was demanding and risky. Nurses and midwives often worked without the protections or formal recognition afforded to physicians, and yet communities relied on them for the most intimate forms of health care: childbirth, disease treatment, postnatal care, household epidemics. Mason’s success suggests she earned trust across a wide social spectrum in Los Angeles.

Her presence also complicates the gendered and racialized history of medicine in the American West. A woman born enslaved becomes, in public memory and in artistic depictions, a medical authority—a healer whose skills were respected even as Black people were routinely denied equality under law. That tension appears in discussions of public artworks that include Mason as a central figure in California medical history, portraying her as a partner in care rather than a subordinate.

This matters not only as symbolism. It is evidence that Mason navigated systems that were designed to keep her marginal, and she did so in a way that produced real power: the power of being indispensable, the power of having people owe you not money alone but gratitude and respect.

Family, community, and the complexities of Black life after emancipation

Mason’s life also included the complicated personal realities that biographies sometimes smooth over. She had children, and her freedom case involved not only herself but family members whose fates were bound together. Her early post-emancipation years were shaped by the need to secure stability for her daughters and to create a social environment in which Black families could survive in a rapidly changing city.

What we can say with confidence is that her household became a node in an emerging Black Los Angeles. The founding of First A.M.E. in her home is one clue; the descriptions of people seeking aid at her door are another. In a period when Black people in California faced discrimination and limited legal protections, the ability to anchor community life in a stable, property-owning household was not merely respectable—it was radical.

The broader context: Slavery’s western edge and California’s historical reckoning

Mason’s story keeps resurfacing in contemporary journalism for a reason. It destabilizes the conventional geography of slavery in the American imagination. Many Americans learn slavery as a Southern institution that ended at the Mason-Dixon line and faded as the West rose. Mason’s life reveals a different map: slavery traveling westward, enslavers attempting to exploit jurisdictional loopholes, and Black people contesting bondage in places that marketed themselves as free.

That is why her name appears in modern reporting about California’s history of slavery and about current debates over reparations and historical accountability. Mason’s life is not just a personal triumph; it is evidence in a larger argument that the West’s development was entangled with slavery and racial hierarchy, even where the law claimed otherwise.

The significance of this context is not abstract. It shapes how institutions teach history, how cities commemorate founders, and how communities argue over what should be remembered in public space. Mason’s presence in public memorials, museums, and civic storytelling is part of that struggle over memory.

Memory, monuments, and the politics of who gets to be a founder

If you walk through downtown Los Angeles today, you can find Mason’s name in the built environment: the memorial park near Spring Street that explicitly honors her life and locates her in the city’s geography. The choice to memorialize her there is telling. Los Angeles, like many American cities, tends to reserve its central commemorations for political leaders, industrialists, and mythic pioneers. Mason’s memorial insists on a different founder: a Black woman, formerly enslaved, whose primary public identity was not office-holding but care and giving.

This insistence is reinforced by the memorial’s design as a timeline embedded with objects. It functions as a public archive, translating historical scholarship and community memory into something pedestrians can absorb in minutes. In that sense, the memorial is not merely honorific; it is pedagogical. It answers a civic question—Who built this place?—with a name many residents may not have learned in school.

Recent reporting underscores that Mason’s descendants and community advocates continue to push for broader recognition of her story, especially in a climate where Black history can be minimized or treated as optional. The stakes of recognition are not about hero worship. They are about whether the public understands Los Angeles—and America—as a place built not only by conquest and capital, but also by the quiet, relentless labor of Black women whose work was often unrecorded unless someone later insisted it mattered.

What Mason’s life teaches about accomplishment

When we list Mason’s accomplishments, the inventory is impressive: she won freedom through the courts; she built a respected career as a nurse and midwife; she acquired property and wealth; she funded and helped found First A.M.E.; she supported people in need; she became a civic figure in early Los Angeles. But the more important lesson is how those accomplishments relate to each other.

Mason’s legal freedom gave her the right to work for herself, but work alone did not guarantee security. She turned work into savings, savings into property, and property into stability. She then turned stability into generosity and institution-building. This is a blueprint, not just a story. It suggests a theory of change grounded in material reality: if you want a community to endure, you create places where people can gather, worship, learn, and be supported; you establish resources that can outlast a single charismatic individual; you use wealth not as a private trophy but as a community tool.

This is why Mason remains such a compelling figure in Black history and women’s history. She demonstrates that the boundary between private life and public life is porous, especially for Black women. Her home became a meeting place. Her work became a network. Her money became a civic fund. Her life became, after her death, an argument that Los Angeles is not only a city of dreamers, but also a city shaped by those who practiced responsibility as a form of freedom.

The ethical challenge: Telling an enslaved woman’s story without turning her into a symbol

Any longform account of Mason’s life must grapple with a reporting dilemma: how to honor the magnitude of her achievements while resisting the temptation to flatten her into an inspirational emblem. The archive is uneven; enslaved people rarely left written records of their own interior lives, and what survives is often mediated through institutions and observers. That means the ethical journalist has to balance narrative force with humility about what can be proven.

What we can responsibly do is treat the contours of her life as historically meaningful without inventing emotional details to fill the silences. The silences themselves are part of the story. They remind us that slavery was not only an economic system but also a record-destroying system, designed to make Black lives legible only when they served white ownership.

Mason’s later visibility—her property holdings, her role in founding a church, her public reputation for charity—shows what happens when a person moves from invisibility by design into visibility by achievement. That transition is rare enough to merit attention, and it is rigorous enough to withstand it.

A conclusion written into the city

Mason died in 1891, but Los Angeles continues to narrate itself through her: through the memorial wall that marks her decades, through the institutions that trace their origins to her living room, and through the recurring use of her story in modern journalism as evidence that the West was never as morally uncomplicated as its myths.

There is a temptation, in telling her story, to treat it as an exception—proof that America’s systems were permeable enough to allow one extraordinary woman through. The deeper truth is more demanding. Mason’s life shows how much had to go right, and how much she had to do, for freedom to become durable. She needed a court willing to recognize the law. She needed allies or witnesses willing to help. She needed skills that could translate into wages. She needed discipline to save. She needed a market in which property could be acquired. She needed a community that could be organized into institutions. She needed health and longevity enough to build a legacy.

That is why her story matters now. It is not only about a single woman’s triumph. It is about the scaffolding required for freedom to become more than a word. It is about the way a Black woman, born into slavery, helped build the civic Los Angeles that later generations would take for granted. And it is about a simple, radical proposition that her life enacted long before it became a slogan: that the open hand is blessed not because it is nice, but because it is how a community survives.

If Los Angeles is a city that prides itself on reinvention, then Biddy Mason is among its most honest inventors. She did not reinvent herself by erasing the past. She reinvented the meaning of the past by refusing to let it be the final claim on her life—and by turning her freedom into an architecture sturdy enough to hold others.