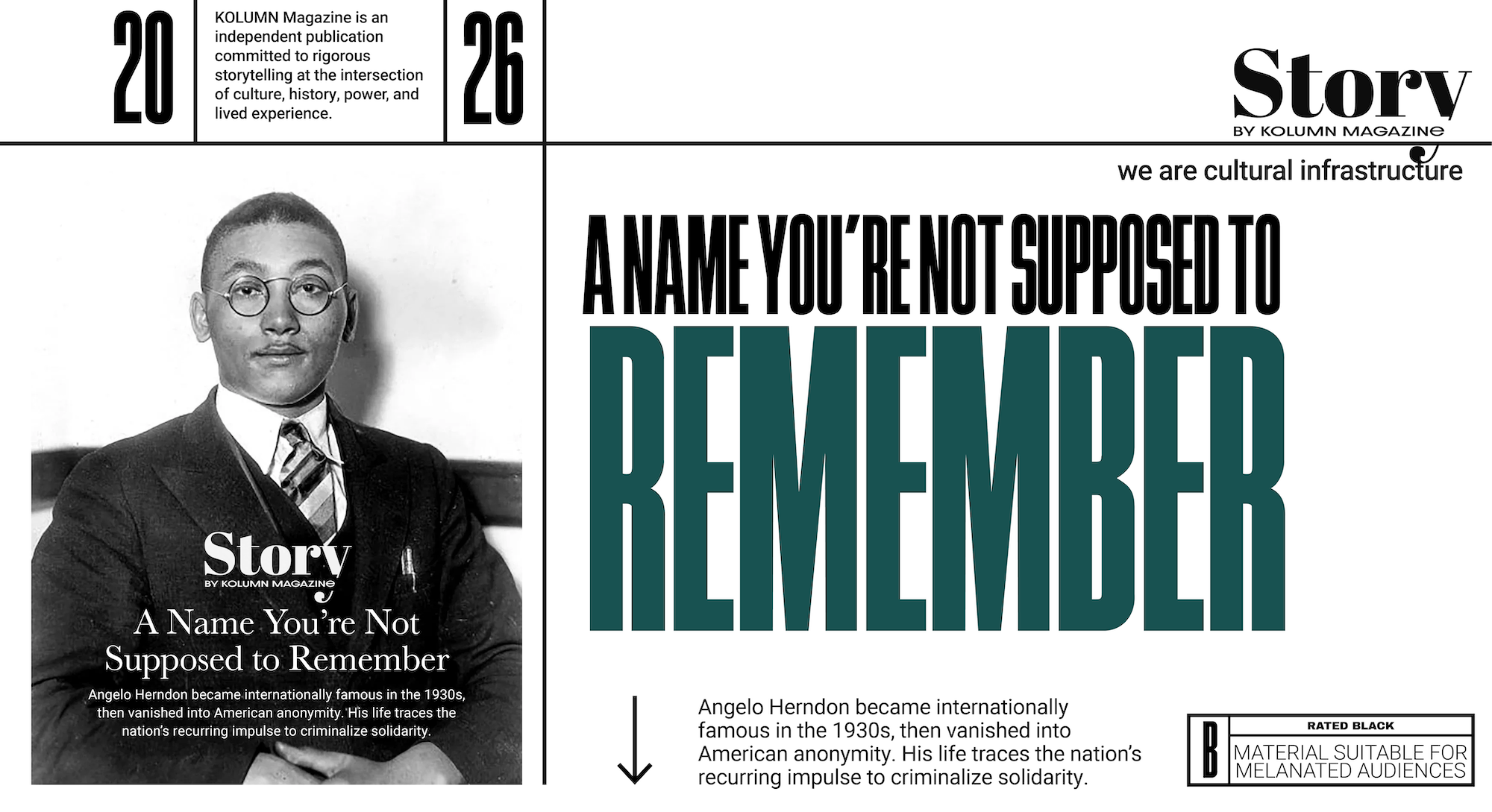

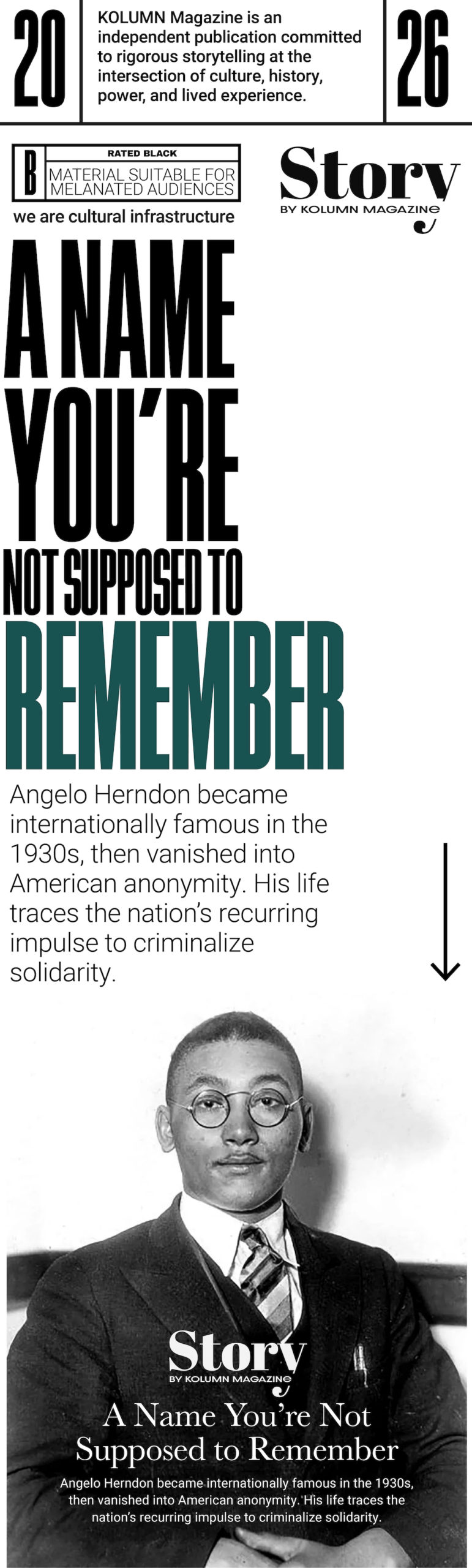

KOLUMN Magazine

By KOLUMN Magazine

In Atlanta, during the summer of 1932, desperation was not an abstraction; it had an address. Relief offices could close. Checks could stop. Hunger could arrive on schedule. The Great Depression had already hollowed out households and wages, and in the South—where Jim Crow made race a governing technology—the burdens of scarcity could be redistributed with the cold precision of custom. What startled Atlanta’s officials was not merely the size of the protest that gathered at the Fulton County Courthouse. It was the composition: Black and white unemployed workers, together, insisting that relief be restored. Local authorities treated that coalition like a contagion. Within days, they would target a teenager who had helped mobilize it—Angelo Herndon—and elevate his politics, his pamphlets, and his very presence into a test case about how far a state could go to punish dissent.

Herndon’s story, too often compressed into a footnote about a Supreme Court decision, is better understood as a full narrative of American fear: fear of interracial organizing, fear of left-wing ideas, fear of the unemployed becoming a political constituency rather than a silent embarrassment. His life and trials expose a pattern that repeats across eras. When authority feels precarious, it looks for a legal vocabulary that can convert political challenge into criminal threat. In 1930s Georgia, that vocabulary came from an “insurrection” statute—an instrument with roots in the state’s historical obsession with preventing revolt, and with a racial subtext that needed no annotation for a Jim Crow jury.

Herndon—born in Ohio in 1913 and pushed into work early—was still a teenager when he moved through the rough circuits of Depression-era labor: mines, transient jobs, and the informal economy of survival that kept working people alive when the formal economy had abandoned them. Accounts of his early life emphasize how quickly the world forced him to adult responsibilities, and how rapidly those responsibilities turned into political clarity. He was drawn into organizing through the Communist Party’s affiliated networks and unemployed councils, which, whatever their ideological commitments, were among the few groups building multiracial relief campaigns at scale in that period.

This is the tension that frames his story and complicates any easy mythology: Herndon’s cause was, at once, deeply local—food, jobs, relief payments—and also entangled in the national and global anxieties of the interwar years, when “radicalism” became a label that could justify extraordinary policing. His activism gave opponents a convenient pretext. But the pretext, as his case revealed, was never the whole truth. The deeper issue was that a Black teenager had helped demonstrate an alternative to the social order: a crowd in which Black and white workers made a single demand of government.

The protest that made Atlanta flinch

The New Georgia Encyclopedia, drawing from the historical record of the case, describes a moment of escalating tension as public relief funds ran thin and officials moved to suspend payments; on June 30, 1932, more than 1,000 unemployed workers marched on the Fulton County Courthouse demanding relief. The next day, county commissioners approved a $6,000 emergency appropriation—an indication, at minimum, that officials understood the protest as a pressure point that could not be ignored.

The details matter because they clarify the state’s later narrative: officials would paint the episode as the edge of rebellion, but their own actions read like classic crisis management in the face of mass hardship. Relief was policy; relief was also politics. To restore payments after a march is to concede that the march has leverage. And leverage—especially interracial leverage—was what Atlanta’s power structure could not tolerate.

Herndon’s organizing role became the fulcrum. According to multiple accounts, authorities monitored suspected “radicals” after the march; Herndon was arrested in July 1932, and a search of his living space uncovered Communist literature. That literature would become, in effect, the state’s most emotionally potent exhibit.

There is a particular American alchemy that turns paper into menace: pamphlets become “plots,” meetings become “conspiracies,” membership lists become “cells.” In Herndon’s case, that alchemy was enabled by Georgia’s insurrection law, which prosecutors used to argue that recruiting for a political organization and holding meetings could amount to an attempt to incite insurrection—an accusation that, in its historical lineage, carried echoes of the state’s older obsession with suppressing Black collective action.

From policing to prosecution: The state builds a “dangerous” teenager

The official story of Angelo Herndon’s “danger” required a kind of narrative inflation. He was young. He was not wealthy. He was not an officeholder or a union boss with institutional backing. The threat he represented was symbolic: the spectacle of a biracial, organized, disciplined demand for public resources during a period of mass unemployment.

The record of the case makes clear that prosecutors leaned heavily on his political affiliations and on the literature seized from him. The University of Minnesota Law Library’s account of Let Me Live and the case history underscores that Herndon was charged with insurrection after authorities found Communist literature, and that he was convicted and sentenced to 18 to 20 years of hard labor on a chain gang before ultimately prevailing at the Supreme Court.

This is where Herndon’s story becomes inseparable from the legal apparatus around him. He did not face the state alone. His defense was taken up by the International Labor Defense (ILD), a Communist-led legal advocacy organization with experience defending high-profile cases involving political repression and racialized injustice (including the Scottsboro Boys appeals).

The ILD’s involvement is not incidental; it shaped both the defense strategy and the public meaning of the case. The state of Georgia wanted to make an example of Herndon. The ILD wanted to make a counter-example: an indictment of Southern justice, and a vehicle for arguing that constitutional rights could not be strangled by vague criminal statutes and racially exclusionary courts.

Two young Black Atlanta attorneys, Benjamin J. Davis Jr. and John H. Geer, were contracted to defend Herndon—an arrangement that mattered in a Jim Crow courtroom not only for legal reasons, but for the symbolism of representation itself. Their work—alongside broader networks of support—turned the trial into a stage where the defense addressed not just the judge but the wider public, a posture captured in later excerpts and reproductions of Herndon’s own words.

Yet the defense faced steep structural constraints. Georgia’s courts were not neutral terrain. The jury was all-white. The political culture was primed to interpret interracial organizing as provocation. And the statute itself—capable of broad, flexible readings—functioned as what modern lawyers might call a “pretextual” tool: a way to punish unpopular speech without admitting that speech was the real target.

The chain gang sentence and the performance of intimidation

Herndon was convicted in early 1933 and sentenced to 18 to 20 years of hard labor on a chain gang. In the public imagination, the chain gang occupies a particular place: part punishment, part spectacle. It is not simply incarceration; it is a warning system. It communicates to the broader community that the state’s power is physical, public, and humiliating.

In the context of Georgia—where convict labor and chain gangs sat near the fault line between slavery’s afterlives and modern punishment—the sentence carried historical weight. It also carried political messaging: a biracial movement for relief would be met not with negotiation, but with a punitive regime designed to break bodies and reputations.

Herndon’s case drew attention beyond Georgia. The fight for his freedom became a cause célèbre in left and civil liberties circles. The point was not simply that a harsh sentence had been imposed, but that the legal theory behind it threatened to criminalize a wide zone of political association and organizing.

The First Amendment Encyclopedia’s summary of the case highlights the basic dynamic: Herndon was charged with attempting to incite insurrection and convicted on a rationale tied to possessing Communist literature; the Supreme Court later overturned the conviction, framing the issue within constitutional protections for speech and assembly.

The long road upward: Appeals, strategy, and the architecture of a constitutional case

The case did not move in a straight line. It moved through a dense ecosystem of lawyers, organizations, and courts, where victories could be partial and reversals could be procedural. The New Georgia Encyclopedia notes that Herndon’s case appeared twice before the U.S. Supreme Court, underscoring how protracted and complex the litigation became.

Behind the scenes, an affiliated network of legal intellectuals and organizations helped shape the appeal. The International Juridical Association (IJA), for example, is documented as reviewing Herndon’s brief and organizing legal support—work that speaks to a broader infrastructure of “movement lawyering” before the term existed.

This mattered because Herndon’s case was not only about what happened to him. It was about what could happen to anyone whose politics were unpopular in a period of civic anxiety. A statute that can be stretched to fit a teenager’s pamphlets can be stretched to fit a union meeting, a civil rights rally, or a community defense organization. The danger of such a statute is not merely the possibility of one wrongful conviction; it is the chill it casts across public life.

The Supreme Court’s intervention: Herndon v. Lowry (1937)

In 1937, the U.S. Supreme Court decided Herndon v. Lowry (301 U.S. 242), reversing the conviction in a closely divided 5–4 decision. Contemporary summaries and later legal commentary emphasize two core points: the evidence did not establish an attempt to incite insurrection in any concrete sense, and the statute—at least as applied and construed—was unconstitutionally vague, failing to provide an ascertainable standard of guilt.

The Supreme Court’s opinion, accessible in the official U.S. Reports PDF, is a document of its time and also a template for future constitutional battles. The Court confronted the state’s effort to treat recruitment for a political party and the holding of meetings—combined with a party doctrine referenced through documents not necessarily shown to the defendant—as criminal “incitement.” In doing so, it signaled limits on a state’s ability to police ideology through criminal law.

This is where Herndon’s case becomes bigger than the immediate facts. Vague statutes are dangerous because they outsource the definition of “crime” to the mood of prosecutors and juries. In a Jim Crow environment, that mood was not hard to predict. The Supreme Court’s decision did not erase the damage already done to Herndon—years of incarceration, the stigma of prosecution, the psychic tax of being made an example. But it did set a boundary: a state could not simply label organizing as “insurrection” without clear standards and evidence.

The Supreme Court Historical Society, reflecting on the case as a free speech battle, underscores how Herndon was charged under a law punishable by death, convicted by an all-white jury, and sentenced to years of hard labor—before ultimately prevailing in a decision that has become part of the constitutional story of dissent.

Why this case still matters: Race, labor, and the state’s fear of solidarity

To tell Herndon’s story with any honesty is to resist the temptation to treat the Supreme Court decision as a neat ending. The decision is a milestone, but it is also evidence of a recurring American problem: the criminalization of political association, especially when that association threatens racial hierarchy.

The state’s anxiety in 1932–1933 was not solely about Communist ideology. It was about the possibility that Black and white workers might recognize shared interests and act in concert—particularly in the South, where the maintenance of segregation depended on preventing precisely that kind of coalition. The protest at the courthouse was, in that sense, a symbolic breach in the wall. And Herndon, because he was young, Black, and politically articulate, could be cast as both scapegoat and warning.

Legal scholars have continued to revisit the Herndon case for what it reveals about constitutional development and the politics of criminal procedure. The case appears in scholarly discussions not merely as a “free speech” episode but as an artifact of how courts, states, and social movements contest power.

It also intersects with a broader, often under-told history: the role of radical and left organizations in building interracial civil rights and labor infrastructure before the postwar civil rights movement’s better-known victories. (This is a point emphasized in works that situate Southern radicalism as part of civil rights’ “radical roots.”)

The personal cost: Fame, exile, and the long fade into ordinary life

Herndon’s public life did not unfold as a simple climb from victim to celebrated elder statesman. In many ways, his biography reflects a different American pattern: a person becomes famous because the state tries to destroy him, and then—after the cameras move on—he is left to rebuild a life in the shadow of that encounter.

His memoir, Let Me Live, published in 1937 and later reprinted, chronicles his experiences with the Georgia judicial and penal systems and remains one of the most direct first-person accounts of the carceral and legal machinery that surrounded the case. The very title reads like a petition and an indictment: a demand for basic life, and a critique of a system willing to crush it.

Over time, Herndon’s relationship to the Communist Party changed; multiple accounts note that he eventually left the Party and lived quietly in the Midwest, working in ordinary occupations. The arc is not unusual for political figures of that era, particularly those whose activism brought long-term surveillance and risk. The Atlanta Journal-Constitution has reported on extensive FBI surveillance records related to Herndon, suggesting the degree to which the state’s gaze lingered beyond the formal end of the case.

Later-life episodes, including a reported 1950s real estate fraud case under an alternate name, appear in secondary reporting and biographical summaries; these accounts underscore, at minimum, that Herndon’s post-fame life did not conform to the heroic, neatly resolved narrative Americans often prefer. If the early period shows the state’s eagerness to define him as a criminal for organizing, the later period shows how easily a public symbol can become a private person navigating messy circumstances—sometimes with damaging consequences—outside the spotlight.

Herndon died in 1997, far from the center of national attention, a detail that journalism historians have noted with a kind of admonition: America is skilled at forgetting the people who force it to clarify its principles.

The supporting cast: Lawyers, institutions, and the hidden infrastructure of civil liberties

One of the most important corrections to the “lone hero” version of the Herndon story is to center the ecosystem that made his legal victory possible.

Benjamin J. Davis Jr., for example, would go on to a prominent political career and face his own later prosecutions; biographical accounts point to the Herndon trial as a radicalizing moment for him. John H. Geer’s role, likewise, is repeatedly cited in case histories as part of a defense team that insisted on confronting the constitutional and racial stakes.

Then there is Whitney North Seymour, a lawyer associated with the appeal; the Washington Post obituary of W.N. Seymour notes his role in defending Herndon and winning the Supreme Court appeal in 1937, while also articulating a broader professional ethic about justice not depending on the popularity of litigants. That line—justice for “the poor and the unpopular”—is not merely an inspiring sentiment. It is a diagnosis of what Herndon’s case required: an insistence that constitutional protections are most meaningful when they protect people whom the majority is comfortable punishing.

Archival holdings also show the seriousness of the defense effort. The New York Public Library lists Angelo Herndon papers, including correspondence, writings, and legal documents connected to his defense—materials that help explain how the case functioned as both litigation and political mobilization.

This infrastructure matters today because it reminds us that landmark legal outcomes rarely arrive by accident. They are built—through fundraising, advocacy, legal drafting, coalition work, and the slow grind of appeals. Herndon’s bail, reportedly raised through broad networks of small contributions, illustrates how the working class, not just elite institutions, helped finance a constitutional fight. (This theme appears in descriptions of the period and the book’s publication history.)

Herndon as a mirror for modern debates about protest and “public order”

It is difficult to read Herndon’s case without hearing contemporary echoes. In every era, governments claim an interest in “public order.” The question is how “order” is defined, and whose disorder is presumed.

When officials interpret protest as threat—particularly protest that crosses racial or class lines—the legal tools that follow often have a familiar shape: broad statutes, discretionary enforcement, and rhetorical escalation (“riot,” “terrorism,” “insurrection”) that paints political activity as existential danger. Herndon’s case is an early, vivid illustration of that pattern. The state’s theory depended on the idea that organizing could be treated as a latent future violence—an indefinite, speculative menace. The Supreme Court’s rejection of that approach, and its insistence on clearer standards, remains one of the reasons the case is remembered within the history of dissent and constitutional law.

It also pushes a harder question: what kinds of movements are permitted to be “popular” without being criminalized? Herndon’s movement—unemployed workers demanding relief—was, by any humane metric, a public interest cause. Yet in the political imagination of Jim Crow Atlanta, it was more dangerous than the poverty it protested.

The unfinished story: Memory, erasure, and why his name returns

If Herndon’s legal victory is a chapter in American constitutional history, his cultural afterlife is a chapter in American forgetting. His name appears in poems and essays and legal scholarship, reemerging when the nation revisits the boundary between dissent and punishment. Productions based on his life have been staged, signaling that artists and community historians continue to find in his story a usable past—one that can speak to present conflicts over work, race, and state power.

The striking thing is how contemporary references often sound like rediscovery rather than continuity. A recent mainstream feature framed him as “overlooked history,” which is accurate, but also telling: Herndon’s “overlooked” status is not an accident. It is a function of what stories are rewarded in public memory. Labor radicalism, interracial organizing, and the role of left institutions in civil liberties wins are all pieces of the past that are easy to sideline when the nation prefers cleaner narratives.

Even the way the case is sometimes summarized—“arrested for possessing Communist literature”—can obscure what authorities were actually responding to: the success of an interracial relief mobilization in a segregated city. Books were the evidence because books were what police could seize. The protest was the provocation because the protest revealed power.

What a fair accounting requires

A thorough, ethically responsible treatment of Angelo Herndon must hold multiple truths at once:

He was a young Black organizer in a period when such a role was itself treated as deviance. He was affiliated with the Communist Party and its organizing networks, which shaped both his possibilities and his vulnerabilities. He was prosecuted under a law that allowed the state to convert political association into “insurrection,” and he was sentenced to years of hard labor—an extraordinary punishment for actions rooted in speech, assembly, and organizing.

He also became a symbol used by many actors: by Georgia officials seeking to intimidate, by civil liberties advocates seeking a test case, by left organizations seeking to demonstrate their commitment to interracial working-class politics, and by journalists and historians who later mined the case for lessons about constitutional fragility. The Supreme Court’s decision in 1937 set limits on state power in this domain, but it did not end the American habit of conflating protest with rebellion.

And his later life—quiet, complex, partly obscure—underscores that the country is better at producing symbols than sustaining the people forced to become them.

In the end, Angelo Herndon’s story is not simply a tale of injustice corrected. It is a reminder of how much injustice can be inflicted before correction arrives, and how narrow the margin can be between freedom and the state’s preferred definition of “order.” A teenager helped a city’s unemployed demand relief. The state answered with a chain gang and the language of insurrection. The Supreme Court answered back—barely. The rest of the story is what it cost, and what it still asks of anyone who believes that organizing for survival should never be treated as a crime.