KOLUMN Magazine

By KOLUMN Magazine

On the riverfronts of the late 1870s—at the muddy edges of the Mississippi, near the rail depots, beneath the gaze of ticket agents and local sheriffs—freedom acquired an unfamiliar posture. It stood in lines. It carried bundles. It looked for passage.

To describe the Exodusters as “migrants” is accurate in the narrowest sense, but it risks missing the point. Migration is often narrated as drift: a demographic tide, an economic adjustment, a movement of bodies responding to the invisible hand. The Exodusters were something sharper. They were people who understood the terms of their confinement and decided to terminate the contract by leaving the jurisdiction.

In 1879 and 1880, thousands of Black Southerners—many recently emancipated or the children of those who were—left states like Louisiana, Mississippi, Texas, Arkansas, and Tennessee, and headed toward Kansas and other western destinations. Contemporary observers called it the “Kansas Exodus” or the “Great Exodus,” and those moving were dubbed “Exodusters,” a biblical name that signaled both the horror they were fleeing and the moral clarity of the decision.

The scale startled the nation and unsettled the South. In the spring of 1879 alone, federal and state accounts described thousands arriving in Kansas—one widely cited figure is more than 6,000 in that season—while relief organizations, city governments, churches, and rail lines struggled to respond.

The Exodusters were not naïve. They were not wandering toward a mythic West because they mistook the prairie for paradise. Many were escaping a post-Reconstruction counterrevolution—an organized campaign of political violence, labor coercion, and civic exclusion that aimed to reduce Black freedom to a legal phrase rather than a lived reality. The Exodusters made a wager: if citizenship was going to be sabotaged in the former Confederacy, perhaps it could be practiced somewhere else.

Kansas—“bleeding” in the 1850s, “free” in the 1860s—offered itself as symbol and strategy. It was a place whose soil had been “washed by the blood” of abolitionist conflict, as one Black letter-writer told Kansas’s governor in 1879, signaling that geography carried moral meaning.

Yet the Exoduster story, told properly, is not simply a morality play of flight from Southern terror to Western promise. It is also a story about the infrastructure of movement, the politics of aid, the limits of sympathy, and the way the nation—briefly confronted with Black people on the move—attempted to decide whether this was a humanitarian crisis, a labor dispute, a political conspiracy, or an embarrassment to be explained away.

It was, in truth, all of those things. And more.

Reconstruction’s end, and the conditions that made leaving rational

The Exoduster movement rose out of a dilemma that is easy to miss if emancipation is treated as a finish line rather than a starting point. The Civil War destroyed slavery as a legal institution, and the Reconstruction amendments redefined citizenship and voting rights. But legal freedom did not automatically translate into secure labor, land ownership, physical safety, or political power. When federal troops withdrew and white supremacist paramilitary violence became a governing tool rather than an outlaw exception, many Black Southerners encountered a brutal discovery: freedom could exist on paper while becoming unlivable in practice

Economics tightened the trap. Sharecropping and debt peonage turned landlessness into a durable form of dependence, especially when merchant credit systems, crop liens, and predatory accounting kept families perpetually behind. Contemporary and later summaries of the period describe how the “emerging system” could amount to de facto re-enslavement by keeping labor tied to landowners and creditors through debt and legal pressure.

Politics made the trap harder to escape. Black voters in many Southern states had been the backbone of Republican coalitions during Reconstruction. When white Democrats regained power—through intimidation, fraud, violence, and “redeemer” politics—Black civic participation became dangerous. Accounts of the era emphasize coercion and assault aimed at keeping Black citizens away from the ballot box, particularly as Reconstruction’s protections weakened.

In this context, leaving was not escapism. It was strategy.

The idea of Kansas as destination had practical and symbolic roots. Practically, the Homestead Act offered a pathway—at least in theory—to land ownership for settlers willing to live on and improve a claim. Symbolically, Kansas carried a reputation as an anti-slavery battleground and a “free state” whose identity had been forged in conflict over whether slavery would be allowed to expand.

But ideas do not move people across hundreds of miles by themselves. People move people. Organizers, circulars, rumors, letters, and sermons—these were the technologies of mass migration in a world where most travelers did not have reliable cash, access to steady rail fare, or trusted information.

One of the most consequential figures in this story is Benjamin “Pap” Singleton, a former enslaved man from Tennessee who became a leading advocate for Black migration to Kansas and is often remembered as a “Father of the Exodus.” Singleton explored land options, encouraged families to consider relocation, and lent the movement the kind of recognizable leadership that turns a private desire into a collective plan.

Singleton was not alone, and the movement did not require a single central command. Scholars of the Exodus emphasize how decentralized and self-propelling it could be—an effect of shared conditions across multiple states and communities. One way to understand the Exodusters is to see them as a grassroots referendum: people responded not to a single leader’s order but to an accumulating consensus that the South was closing around them.

The name “Exoduster,” and the politics of biblical language

The biblical framing was not decorative. It was analytic.

To call oneself an Exoduster was to place contemporary suffering into a sacred story of escape from bondage—one that made oppression legible and departure morally coherent. In a society that constantly questioned Black intelligence, capacity, and citizenship, biblical language allowed migrants to claim a narrative with authority: this was not vagrancy or laziness, but deliverance.

That framing also served a practical purpose: it unified people with different origins, different skills, and different immediate reasons for leaving into a shared moral vocabulary. When thousands of individuals make the same decision—often with incomplete information—narrative becomes infrastructure. It is what allows a mass action to feel intelligible to the people doing it.

Yet that narrative was contested. White Southern elites often insisted the Exodus was stirred up by “agitators” or partisan manipulation. National politicians debated whether the migration was a humanitarian emergency or a scheme—one suspicion being that Republicans were “importing” Black voters into key states ahead of the 1880 election cycle. The very fact that such accusations gained traction reveals how readily the country treated Black mobility as illegitimate unless it served white economic needs.

This is one of the Exodusters’ enduring lessons: when Black Americans move to protect themselves, the nation often responds by interrogating motives rather than conditions.

How an exodus actually happens: Routes, bottlenecks, and the geography of hope

The Exodusters did not travel as a single river of people sweeping west. They moved in pulses, through chokepoints, along routes shaped by steamboat schedules, rail prices, and the willingness of carriers to transport them.

A common corridor ran up the Mississippi River to St. Louis, which functioned as a crucial halfway point—a place where migrants could regroup, seek aid, and try to secure passage onward into Kansas. Accounts of the Great Exodus describe St. Louis as pivotal, and they underline how frequently migrants arrived with too little money to complete the journey.

And so, inevitably, there were scenes that resembled refugee crises more than pioneer romance: people stranded, waiting, relying on mutual aid, sleeping in makeshift conditions while local institutions debated responsibility. The story of St. Louis—Black churches, aid boards, and community networks trying to respond while officials sometimes discouraged the migrants—illustrates how Black migration has often depended on Black infrastructure even when the crisis is produced by broader political failure.

Kansas entry points included river towns like Atchison and Kansas City, with onward travel by rail to places such as Topeka, where organized relief infrastructure emerged. Local history accounts note that Topeka became a key node, with the state’s governor forming the Kansas Freedman’s Relief Association in 1879 to provide aid to destitute newcomers and facilitate settlement.

But movement was not just a matter of logistics; it was also a matter of vulnerability. Travel made migrants visible, and visibility made them a target for exploitation. Ticket agents could overcharge. Employers could promise work that never existed. Local authorities could harass, arrest, or “warn out” newcomers as public burdens. Even in places that did not share the South’s particular forms of racial terror, racism remained a portable condition of American life.

The Exodusters were betting that conditions would be better, not perfect.

The Senate investigation: When testimony became an indictment

In 1880, the federal government investigated the “Negro Exodus from the Southern States,” producing hearings and testimony that function today as a rare archive of Black voices describing the post-Reconstruction South in their own terms. A National Archives account compares the value of this testimony to other landmark collections of first-person Black accounts, emphasizing how it reveals what freed people feared, needed, and understood about the society forming around them.

This matters because power often controls the record. In the 19th century, the voices of Black farmers and laborers were frequently filtered through white journalists, officials, or employers. The Senate investigation, whatever its political motives, created a formal space where Black witnesses could articulate conditions—violence, political intimidation, economic coercion—that made migration the only rational option.

Benjamin Singleton testified in 1880, describing his background and the migration effort, providing a direct window into how leaders framed the movement and how they navigated a nation that alternated between curiosity and hostility.

The hearings did not produce sweeping federal relief. Politics intruded, and congressional action stalled. Yet the testimony itself remains a kind of moral document: evidence that Black Southerners did not passively endure the erosion of their rights but diagnosed it, described it, and acted against it with the means available.

Kansas: The promise, the prairie, and the price of arrival

If the South was the place being fled, Kansas was the place imagined. The reality was mixed.

Many Exodusters arrived with limited resources and faced punishing conditions: scarce housing, unfamiliar climate, and the difficulty of securing good farmland in an environment already shaped by speculation, rail interests, and the uneven distribution of opportunity. Historical summaries of Black migration to Kansas emphasize that aid societies provided food and supplies and that land acquisition was often more difficult than the promise implied.

Some settled in cities and towns, finding domestic work, trade labor, or service employment; others attempted rural homesteading, which demanded tools, seed, capital, and time—precisely what many migrants lacked. A core tension emerges here: land ownership was central to the dream, but the mechanics of land ownership required capital and stability that the migrants, by definition, did not have when they arrived.

Still, Black settlement did occur, and it mattered. Kansas’s Black population rose during the decade, and the migration contributed to the creation and reinforcement of Black communities that anchored political life, education, and church networks across the state.

Perhaps the most symbolically resonant settlement tied to the Exoduster era is Nicodemus, Kansas—founded in the late 1870s and remembered as the oldest remaining Black settlement west of the Mississippi River. The National Park Service frames Nicodemus as a representative site of Black involvement in homesteading and the pursuit of freedom in Kansas, preserving it as both place and symbol.

Nicodemus is often narrated as triumph and trial in the same breath. Accounts describe dugouts and sod structures, harsh weather, shortages of tools and supplies, and disillusionment—yet also determination, institution-building, and the emergence of churches and civic structures that made the settlement more than a temporary camp.

The persistence of Nicodemus—through railroad disappointments, economic shifts, and demographic decline—helps explain why the Exoduster movement should not be reduced to a single year’s headlines. Even when the peak Exodus subsided, the broader pattern of Black western migration continued, and the political meaning of Black settlement in the West remained alive.

Aid, philanthropy, and the discomfort of the North

The Exodusters forced a question that American politics repeatedly tries to avoid: what obligations does the state have when citizens are displaced by political violence and economic coercion inside its own borders?

Kansas organized relief. Black churches and communities organized relief. Philanthropists and aid societies participated. Yet the overall response often carried the tone of temporary charity rather than structural accountability. The formation of relief associations in Kansas—explicitly tasked with aiding destitute freedmen, refugees, and immigrants—shows that the crisis was legible as mass displacement.

But “relief” can be double-edged. It can save lives while reinforcing the idea that the displaced are burdens. It can turn political injustice into a charitable cause, shifting the focus from perpetrators to the suffering of the displaced. In the Exoduster story, this tension appears in debates over whether migrants “deserved” aid, whether they had been manipulated, and whether their movement threatened local labor markets.

These are familiar dynamics in American history: the displaced are asked to justify their displacement, and the communities that receive them are encouraged to treat the problem as theirs rather than the nation’s.

Critics, cautions, and the argument over timing

Not every prominent Black leader celebrated the Exodus. Some argued that leaving conceded too much territory to hostile forces, or that the movement was poorly organized and risked disaster for the people involved.

This internal debate is important because it reveals how seriously Black Americans treated political strategy. The Exodusters were not simply reacting; they were choosing among flawed options in a hostile environment. Should one stay and fight for rights where one lives, risking death and economic ruin? Or should one relocate, seeking a jurisdiction where rights might be more secure?

The fact that the Exodus happened at scale indicates how many people concluded that staying had become too costly, too dangerous, and too uncertain.

Women, children, and the everyday labor of survival

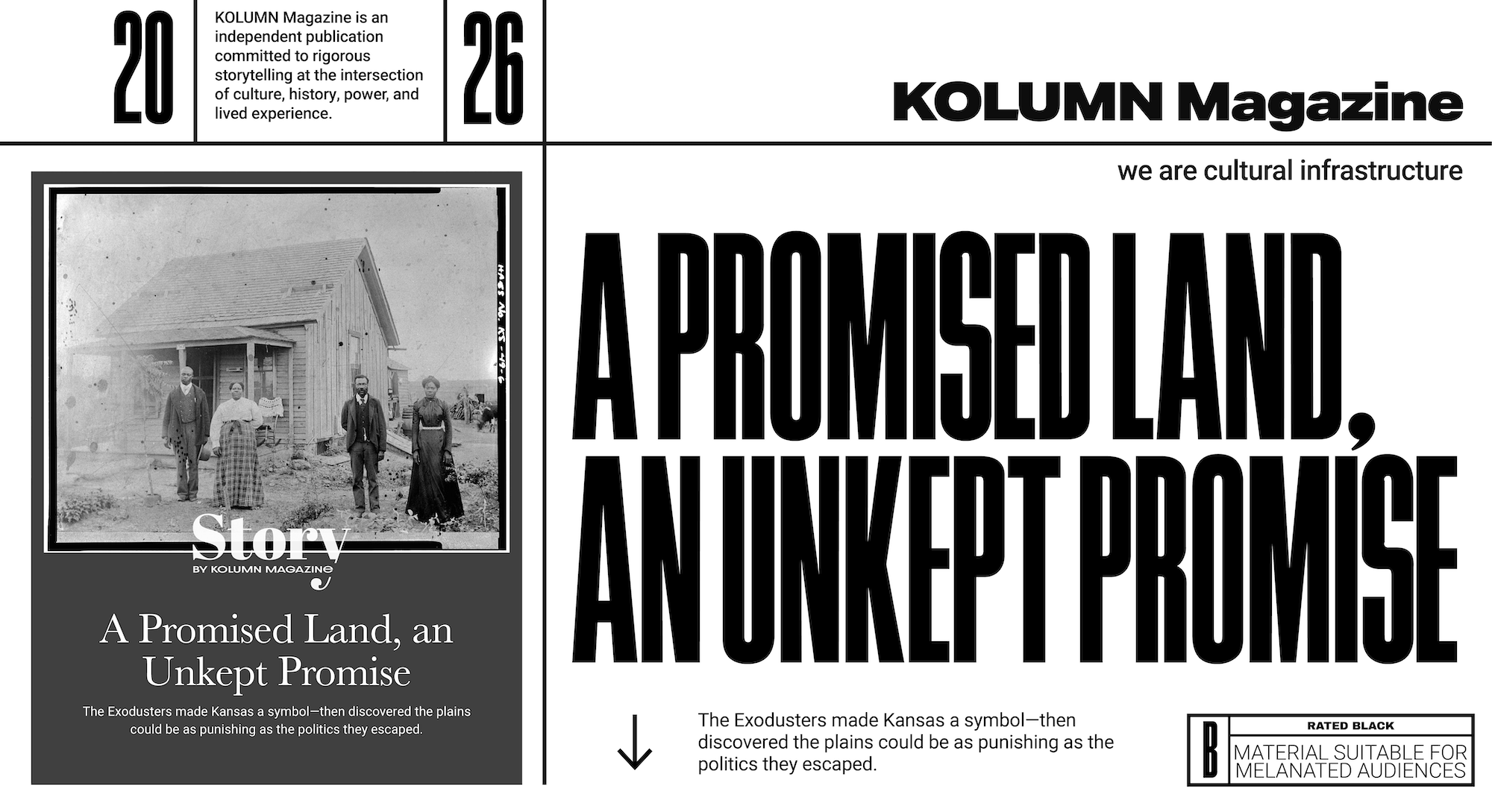

The iconic images of the Exodusters—families moving with carts, bundles, children in tow—can flatten the complexity of who made the migration work. But the movement depended on domestic logistics and caregiving labor: feeding families on the road, tending illness, managing scarce resources, improvising shelter, and sustaining morale.

Visual depictions from the era show families traveling together, emphasizing that this was not only a movement of male laborers chasing opportunity; it was a communal decision with multigenerational stakes.

This matters because the very definition of freedom was at stake in family form. Slavery had been, among many other things, a system that disrupted kinship through sale, forced separation, and sexual violence. The act of moving as a family—however precariously—was itself a claim: we will decide where we live, together.

The Exodusters and the long arc of Black mobility in America

If the Great Migration of the 20th century is often treated as the defining episode of Black internal migration, the Exodusters complicate that storyline by showing how early—and how decisively—Black mobility functioned as political action.

A Washington Post assessment of Nell Irvin Painter’s landmark work on the Exodusters described the 1879 migration as “the first act of a drama” that culminated in mass movement to Northern cities in the following century. The phrasing is telling: the Exodusters were not an isolated incident but an early, defining chapter in the history of Black Americans using movement to renegotiate power.

To see the Exodusters clearly is to recognize that Black migration has repeatedly been driven not only by labor markets but also by governance—by the question of whether a place will allow Black people to vote, own property, educate their children, and survive.

And it is to recognize that the nation’s response has often been temporary attention followed by strategic forgetting. The Exodusters briefly became national news and congressional subject matter; then they were absorbed into the broader mythology of westward expansion, a mythology that often centers white settlers and treats Black presence as peripheral.

But Black people were never peripheral to the American frontier. They were among its builders, its farmers, its soldiers, its town founders, and its political actors. The Exodusters were one of the clearest demonstrations of that truth: a movement in which Black Americans claimed the frontier not as escape, but as assertion.

Nicodemus as a living archive

Today, Nicodemus persists as a kind of living archive of the Exoduster era—not because it preserves a flawless success story, but because it preserves evidence of intent.

The National Park Service describes Nicodemus as a representation of formerly enslaved people leaving the post–Civil War South to seek freedom in Kansas and preserves the site to interpret that history for future generations.

The persistence of the town also highlights a quieter reality: many Exoduster settlements did not survive, not because the dream was foolish, but because the economic and environmental barriers were high and the nation’s support was limited. The story is therefore not simply about perseverance; it is about what perseverance was required to compensate for.

In that sense, Nicodemus is not only a monument to those who left. It is a question posed to those who remained behind in power: why did freedom require this much distance?

What the Exodusters reveal about American democracy

The Exodusters force a fundamental reconsideration of how democracy is practiced and protected.

If Black citizens must flee to enjoy the rights guaranteed by constitutional amendments, then democracy has become regional, conditional, and unstable. If violence and economic coercion can push citizens out of their home states, then migration becomes an instrument of domestic displacement—a tool by which power reshapes electorates and labor markets without passing a law.

The 1880 Senate investigation—its testimony, its political debates, its limited outcomes—shows that the federal government recognized the crisis but struggled to treat it as an indictment of governance rather than a puzzle about Black behavior.

That struggle did not end in 1880.

The Exodusters are therefore not only a story about Kansas. They are a story about the United States confronting, however briefly, the meaning of Black citizenship in the aftermath of slavery—and watching thousands of citizens declare, through motion, that emancipation without protection is not enough.

They left with bundles, yes. But they also left with an argument. It was addressed to every courthouse, every statehouse, every federal committee room: if you will not enforce our rights here, we will try to live them elsewhere.

And in doing so, they made one of the most consequential political statements of the post–Civil War era—one that deserves to be remembered not as footnote, but as framework.