By KOLUMN Magazine

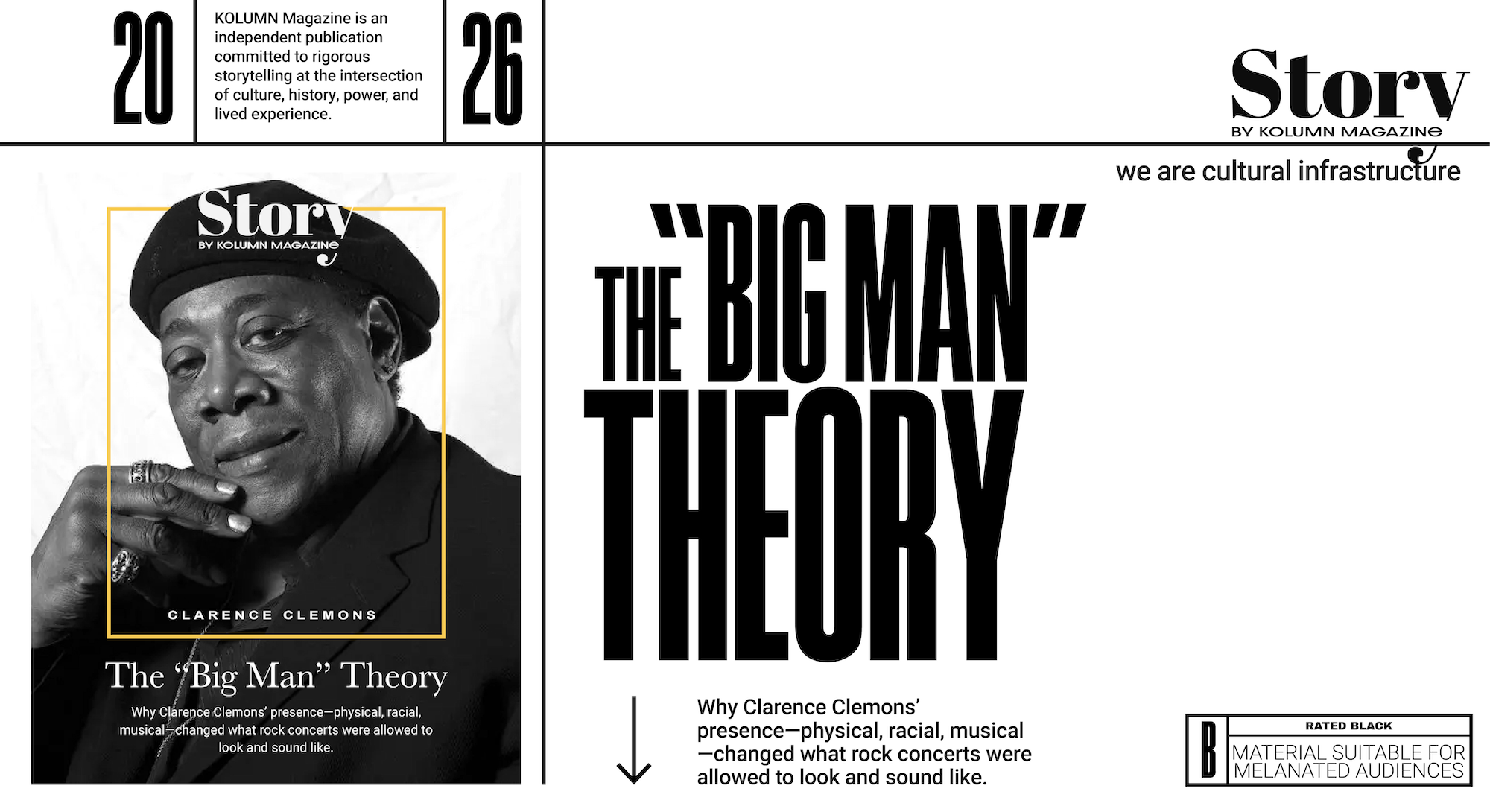

On stage, Clarence Clemons was introduced like a folk hero: the “Minister of Soul,” the “King of the World,” the “Master of Disaster.” In the hands of Bruce Springsteen, those nicknames were less hype than dramaturgy—part of a running narrative that helped turn rock concerts into something closer to theater, revival meeting, and neighborhood block party at once. Clemons, towering and gleaming, would step forward with a saxophone that looked almost undersized against his frame, and the audience would cheer before he played a note. Then he would play, and the cheer would change shape—into recognition. Not of virtuosity, necessarily, but of arrival: the moment a song’s emotions become physical, the moment the room’s temperature rises.

The “Big Man” label was, of course, literal. Obituaries and tributes routinely noted Clemons’ imposing height and build, the athletic past that might have carried him elsewhere if knees and circumstance had cooperated. But the nickname also obscured what he actually mastered: the ability to be essential without being centered, to become a co-star in a genre that often treated bandmates as replaceable machinery. In rock history, that’s not a small feat. In American history, it’s even less so, because Clemons’ visibility—and his partnership with Springsteen—played out inside a culture industry long structured by segregation, gatekeeping, and the selective borrowing of Black sound.

To write about Clemons honestly is to write about the distances he traveled: from Norfolk County (now Chesapeake), Virginia, into the churn of the Jersey Shore music scene; from R&B covers and local bands into the most mythologized bar-band-to-stadium arc in rock; from supporting roles into a national image of interracial brotherhood so iconic it could be summarized in a single photograph—Springsteen leaning on Clemons on the cover of Born to Run, casual and conspiratorial, as if the future were already decided. The Guardian later called that image defining—an emblem of fraternal bonding that fueled the band’s rise.

But photographs are neat, and lives are not. Clemons’ story includes reinvention and reinjury, spiritual searching and chronic pain, pop-culture detours (yes, Bill & Ted), and an end marked by medical crisis and, later, a family claim that the stroke that killed him might have been preventable. It includes a body of work outside E Street that many casual listeners never fully mapped: a mid-’80s hit duet with Jackson Browne, a signature cameo on Aretha Franklin’s “Freeway of Love,” late-career collaborations with Lady Gaga that placed him inside a different generation’s mainstream.

And it includes something harder to measure: how a Black musician, in a predominantly white rock ecosystem, became both symbol and person—celebrated, sometimes flattened, occasionally exoticized, and yet persistently himself.

A Virginia beginning, an athlete’s body, a musician’s route

Clarence Anicholas Clemons Jr. was born January 11, 1942, in Virginia. Accounts of his early years often emphasize both discipline and restlessness: a young man shaped by church, community expectations, and the era’s racial boundaries, but pulled toward the expressive permission of music. BlackPast, in its biographical overview, situates Clemons within a lineage of African American artists whose careers required navigating not only the craft but the country that received it.

He also had the body of a different kind of American dream. Before he became a cornerstone of Springsteen’s sound, he was a serious athlete. The University of Maryland Eastern Shore—then Maryland State College—has commemorated Clemons as a football player as well as a musician, underscoring how plausible that path once seemed.

The pivot away from sports is not just trivia; it frames the way Clemons later inhabited rock stardom. His physical presence carried the authority of someone who could have belonged to a different spectacle altogether. On stage, he could loom without threatening, radiate power without bullying. It helped him play a paradoxical role: the gentle giant, the flirt, the winking enforcer who could “bless” a song into lift-off.

His working life before fame is equally revealing. Biographies highlight that he worked as a counselor at the Jamesburg Training School for Boys in New Jersey during the 1960s—work that placed him in the daily realities of young people on the margins, long before he became a symbol in a national cultural narrative. That detail complicates the mythology. Clemons was not hatched inside the glow of rock clubs; he had a day job with consequences.

The Jersey Shore crucible, and the meeting that became legend

If rock history loves anything, it’s a creation story. Clemons and Springsteen have one of the genre’s best: two aspiring lifers in a stormy coastal scene, crossing paths at exactly the moment when a band becomes a band. Variations of the story appear across interviews, biographies, and fan archives. Wikipedia’s summary of the mythology notes the setting—Asbury Park, the Wonder Bar, nearby clubs—and the way the meeting entered the E Street narrative, even becoming embedded in Springsteen’s stage patter and songs like “Tenth Avenue Freeze-Out.”

What matters is not the exact weather report of that night but what the story allowed: it framed an interracial partnership as destiny rather than exception. In an America where interracial intimacy has always been policed—legally, socially, violently—rock presented the two men as brothers-in-arms, and audiences were invited to cheer that bond as part of the show.

This is where journalistic caution matters. Myth can be a way of hiding the labor underneath: the rehearsal hours, the economic precarity, the negotiation of ego and respect. But myth can also be a way of expressing a truth that statistics can’t hold. Clemons did not merely join Springsteen; he joined the story Springsteen was telling about the America in his songs—romantic, bruised, striving, class-conscious, often obsessed with escape. Clemons’ horn became one of that story’s most dependable narrators.

What the saxophone did on E Street

Clarence Clemons is often described as a sideman, a term that can sound like diminishment. But in the E Street Band, “sideman” was closer to “co-author.” David Remnick wrote, in a 2011 tribute, that Clemons was not an entirely original player in the technical sense—he was a vessel of many soul, gospel, and R&B influences—but he was “irreplaceable,” essential to both the band’s sound and spirit. That formulation—vessel and essential—gets at the core.

Clemons’ saxophone parts were rarely ornamental. They were structural. They created transitions, underlined emotional turns, and—when Springsteen’s lyrics reached the edge of what language could carry—took over.

Listen to how fans and critics describe the function of his solos: not “flashy,” but declarative. Not “jazzy,” but narrative. The saxophone in Springsteen’s universe is a voice from the street: it can be comic, erotic, mournful, triumphant, sometimes all in one song. In performance, Clemons didn’t just play; he acted. He approached solos like scenes. He could lean into the microphone, flirt with the front rows, and then deliver a phrase that made the song feel newly alive.

Branford Marsalis offered a bracingly honest assessment of Clemons’ playing: in Marsalis’ view, Clemons’ lack of conventional “prowess” meant he had to get there through attitude, sound, and conviction—qualities that served Springsteen’s music, which prized honesty and force over polish. Marsalis’ point is not that Clemons was limited; it’s that Clemons was perfectly engineered for the job. In rock, the hardest thing is often not speed but weight: making a note feel inevitable.

That “job” was also physical. Touring with Springsteen meant sustaining a level of intensity that would challenge even healthier bodies. Later accounts—including interviews and biographies—describe Clemons’ chronic pain and multiple surgeries, and the way performance could become punishing. The spectacle of the Big Man suggested invincibility; the reality was endurance.

The cover of Born to Run and the politics of an image

The cover of Born to Run is now museum-grade iconography: Springsteen, young and wiry, leaning into Clemons, who smiles as if he knows something the audience doesn’t. The Guardian obituary argues that the image helped define the album itself, symbolizing the intense bonding that powered the band’s ascent.

It’s also an interracial image of casual intimacy, mass-distributed in 1975 America. That fact is sometimes treated as incidental, but it shouldn’t be. The post–civil rights era did not dissolve racial anxiety; it rearranged it. Popular culture became one of the arenas where integration could be performed—even celebrated—while material inequalities and structural racism persisted.

Samuel G. Freedman, writing for The Root, approached the Springsteen–Clemons partnership with what he called a “buddy movie” lens, attentive to how the pairing could flirt with stereotype even as it demonstrated genuine friendship and mutual dependence. Clemons, Freedman notes in author bio context, is introduced with titles that can read like pageantry—“Emperor,” “King,” “Minister of Soul”—while Clemons sometimes dressed in ways that played with archetypes of preacher and pimp.

Here is the tightrope: Clemons benefited from visibility that many Black rock instrumentalists did not receive, but visibility in a white-led rock project can come with a cost—being cast as symbol, being asked (implicitly) to confirm a white artist’s openness, being read through the audience’s fantasies. Clemons was savvy about performance; he understood theater. He also had to live inside it.

If you want an emblem of how complicated this could be, consider how often tributes to Clemons pivot quickly to Springsteen’s feelings. Even in grief, Clemons can be narrated as supporting character. That is not malicious; it’s structural. But Clemons’ story deserves to be told as his own—an American musician who made himself unavoidable.

Beyond E Street: Hits, features, and the breadth of his musicianship

One way to capture Clemons’ agency is to track the work he did outside the Springsteen orbit.

In 1985, Clemons scored a notable hit with “You’re a Friend of Mine,” a duet with Jackson Browne. The song’s success matters because it challenged the idea that Clemons was famous only as a sideman. It also placed his voice—not only his horn—front and center. This was Clemons as lead presence, not just featured texture.

That same year, he became inseparable from another kind of pop memory: Aretha Franklin’s “Freeway of Love,” where his saxophone is part of the song’s celebratory engine. The track is widely documented as featuring Clemons’ notable contribution, and he appears in the video as well. If Springsteen’s sax was about yearning and escape, Aretha’s was about motion, pleasure, and dominance—the Queen of Soul driving the whole thing. Clemons could live there too, because his sound—big, declarative, warm—was adaptable.

His later years brought perhaps the most surprising mainstream cameo: Lady Gaga. In early 2011, Rolling Stone reported on how Clemons ended up on Gaga’s album Born This Way, noting he played sax through “The Edge of Glory” and delivered a solo. “The Edge of Glory” also carried an elegiac context for Gaga, inspired by the death of her grandfather, making Clemons’ horn feel like a bridge between generations of pop’s emotional languages. There is poignancy here: days before his stroke, Clemons shot the music video for “The Edge of Glory,” according to biographical summaries. Late-career relevance is not guaranteed for rock musicians of Clemons’ era; he earned it.

Clemons’ collaborations extended beyond pop. Biographical sources note friendships and performances with figures in the Grateful Dead universe, including Jerry Garcia, and later sit-ins with related projects. The point is not to build a résumé; it is to show that Clemons’ musical identity was not confined to one band’s mythology.

Acting and popular culture: The Big Man as character

Clemons also had a parallel career that feels, in retrospect, like an extension of his onstage persona: he acted. He appeared in Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure as one of the “Three Most Important People in the World,” an odd, memorable cameo that made his face familiar to audiences who may not have known E Street.

Filmographies note additional appearances, including a role in Martin Scorsese’s New York, New York and television work. It can be tempting to treat this as novelty. But there’s a deeper throughline: Clemons understood presence. He was not merely a musician who happened to show up on camera; he was a performer who understood how to fill space, how to communicate with expression, posture, timing.

In rock, instrumentalists often become faceless labor behind a frontman. Clemons refused that. Acting was one more venue where he could be seen.

Spiritual searching, the private man behind the public giant

Public narratives about Clemons often fixate on charisma. Yet his later years included a spiritual search that surprised some fans who knew him mostly as swagger. Accounts connected to Sri Chinmoy’s community describe Clemons’ relationship with the teacher, including the spiritual name Clemons received: Mokshagun, translated as “Lord’s All-illuminating Liberation-Fire” in Chinmoy’s Bengali. Whatever one makes of Chinmoy’s broader cultural footprint, the fact of Clemons’ participation suggests a man seeking grounding beyond applause.

A documentary released years after his death leaned into that dimension. Clarence Clemons: Who Do I Think I Am? is described by outlets and listings as an intimate portrait that includes his search for enlightenment and meaning in the final years of his life. The film’s framing matters: it implies Clemons was not satisfied to be only a rock archetype. He wanted a language for his inner life.

This is also where the body re-enters the story. Biographical accounts describe extensive health challenges—knee and hip replacements, spinal surgery, chronic pain—complicating the Big Man myth of perpetual strength. For performers, spirituality can be a way of surviving the contradiction between public invulnerability and private fragility.

The end: Stroke, grief, and the legal afterlife of a death

In June 2011, Clemons suffered a stroke at his Florida home and died days later at age 69. Major outlets—including The Washington Post and The Guardian—reported the basic chronology and the sense of cultural loss that followed.

Grief quickly became public text. Springsteen’s eulogy for Clemons circulated widely, with reprints and excerpts across cultural sites and news blogs. The eulogy’s power lies partly in its refusal to sanitize: it describes Clemons as difficult, radiant, confusing, beloved. It also frames their partnership as protective—an interracial pairing that made Springsteen feel “safe” in his own skin while making Clemons feel seen. That formulation matters because it acknowledges exchange rather than charity: Clemons was not a token or accessory; he was a partner who shaped Springsteen’s identity as a performer and, arguably, as a public moral voice.

Two years later, the story gained a legal coda. In 2013, The Guardian reported that Clemons’ family claimed his death involved medical negligence and that they were suing doctors for malpractice. Pollstar summarized allegations that physicians failed to administer a short-term blood thinner (Lovenox) around a surgery, framing it as a key part of the complaint. These claims do not rewrite the life, but they do underscore the vulnerability behind the legend: even famous bodies can be mishandled; even adored artists can become patients navigating risk.

Race, rock, and the problem of being “exceptional”

Clarence Clemons’ career invites a larger question: what does it mean for a Black musician to be canonized in a genre marketed as predominantly white, even when that genre is built on Black musical foundations?

Clemons’ presence in E Street was both corrective and exceptional. Corrective because it placed a Black instrumental voice at the center of one of rock’s most enduring acts; exceptional because the industry did not produce endless equivalents. The horn section in rock has often been a signifier of R&B inheritance—borrowing Black sonic vocabulary to amplify feeling. Clemons, by contrast, was not a borrow; he was an authorial source inside the machine.

Yet even that status came with complications. Freedman’s Root essay reads the Springsteen–Clemons partnership not only as friendship but as image-making, attentive to the ways Clemons’ size and styling could be read through stereotypes as well as through self-aware play. This is not an accusation; it is an analysis of how American audiences consume Black male presence—especially in entertainment—through a preloaded set of myths about power, sexuality, danger, humor, and salvation.

Clemons navigated this with a performer’s intelligence. He leaned into pageantry because pageantry was part of the show, but he also insisted—through his musicianship—that the show could not happen without him. That insistence is why, when he died, critics did not merely say “a band member is gone.” They said something more like: an ingredient has vanished, and the recipe will never taste the same.

The sound as personality: Why technical debates miss the point

It is common, in musician-to-musician commentary, to weigh Clemons against saxophone virtuosos. Marsalis’ assessment—clear-eyed, respectful—offers a useful way through the trap: Clemons’ greatness was not the greatness of the conservatory. It was the greatness of the gig, the song, the moment.

Rock history is full of technically superior players who failed to leave a cultural imprint. Clemons left one because his sound carried personality. It communicated generosity. It communicated appetite. It communicated that the party was for you, too.

Even his late-career pop moment with Gaga demonstrates this. Gaga is an artist of maximalism and theatrical sincerity; Clemons fit because he understood how to make sincerity big without making it corny. In an era of digital production, his breath through brass was unmistakably human.

Legacy: What remains when the Big Man leaves the stage

After Clemons’ death, the E Street Band faced a practical question as well as an emotional one: how do you cover a part that is sonic and symbolic? Jake Clemons, Clarence’s nephew, later took up the saxophone chair in the band, and coverage of that transition emphasized that he was not “replacing” his uncle so much as honoring him while carrying his own identity.

But even when the notes are played, the presence is different. Remnick’s tribute captured that irreplaceability as a matter of camaraderie as much as sound. The Atlantic, reflecting on Springsteen’s public grief and the larger cultural response, pointed readers to analyses that treated Clemons and Springsteen as more than bandmates: as a partnership with racial and emotional resonance, a kind of American parable that people needed when he died.

The documentary portrait adds another layer: Clemons as seeker, not just showman. And the legal dispute around his death adds a final, sobering modern layer: even legends can end in paperwork, allegations, and unresolved questions.

So what is Clarence Clemons’ legacy, beyond the saxophone solos that still trigger a reflexive smile?

It is, first, a lesson in presence as authorship. Clemons did not write most of Springsteen’s lyrics. But he authored emotional climaxes; he authored atmosphere; he authored a sense of welcome. That is composition by other means.

Second, it is a lesson in interracial partnership that is neither fantasy nor sermon. The Springsteen–Clemons bond became iconic because it looked easy—two men leaning on each other, literally and musically. Yet America rarely makes such ease available without cost. Their visibility suggested possibility, but it also risked becoming a comforting story that audiences could consume instead of confronting harder truths about race. Freedman’s critique remains useful precisely because it refuses to let the image become innocent.

Third, it is a lesson in how Black musicians persist inside—alongside—industries that profit from Black sound. Clemons was not merely included; he was foundational. Still, his story stands out partly because there were not enough stories like it.

Finally, it is a reminder that the most durable art often comes from human contradictions: the giant who carried pain; the swaggering performer who sought spiritual quiet; the “sideman” who became a symbol; the man whose myth was loud but whose instrument—at its best—could sound like a voice speaking plainly, directly, to whoever needed it.

That is the Big Man’s real scale. Not inches or pounds, not even decibels, but capacity: the capacity to take the private feelings of a roomful of strangers and make them feel, for a few minutes, like a shared language.