KOLUMN Magazine

By KOLUMN Magazine

In New York, history often arrives as architecture: a cast-iron façade, a brownstone cornice, a plaque at eye level. But Black history—especially Black self-determination—has frequently survived in forms that are easier for a modern city to pave over: a set of property deeds, the memory of a schoolhouse, a church basement that served more purposes than worship, a mutual-aid practice passed from household to household.

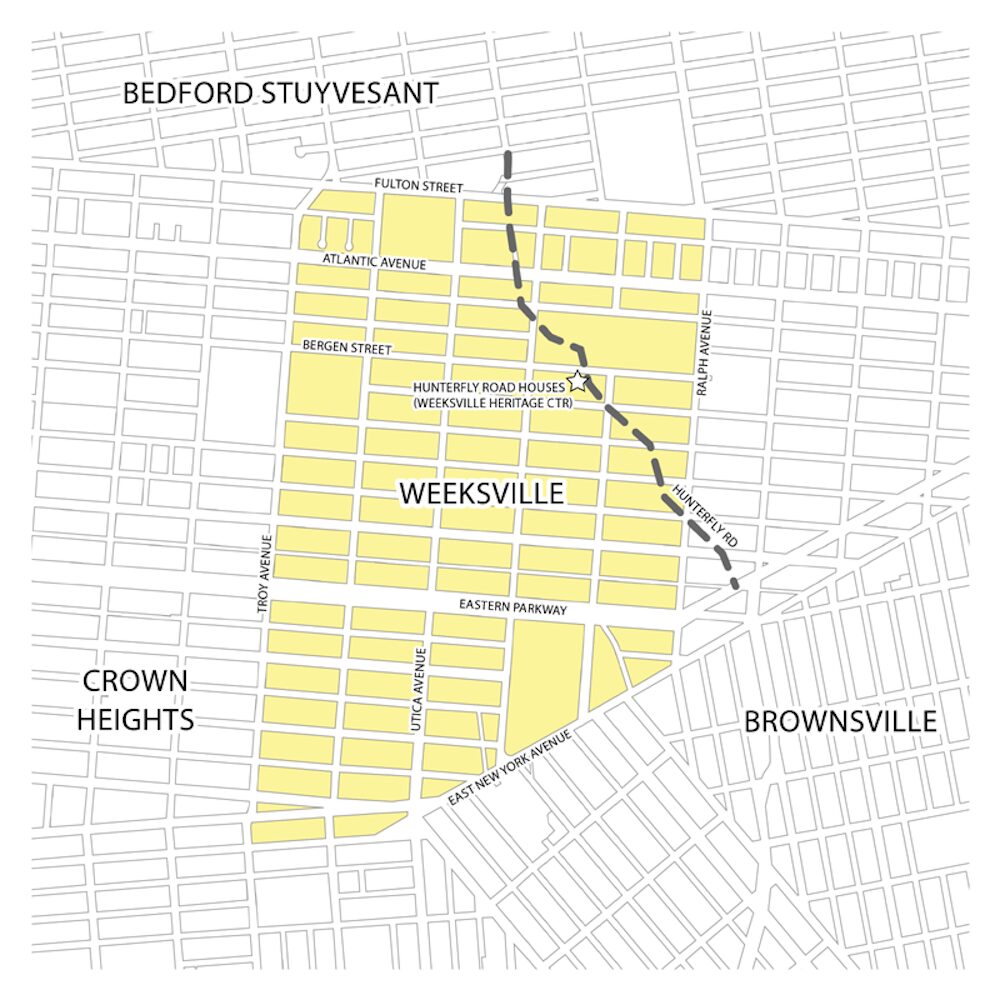

Weeksville, a 19th-century free Black community in what is now central Brooklyn (today associated with Crown Heights and surrounding neighborhoods), is a case study in that quieter form of endurance. Founded in the 1830s by free Black New Yorkers seeking both safety and autonomy, Weeksville developed the institutional density of a small town: churches and schools, civic associations and care institutions, Black-owned print culture, and a political base anchored in something that mattered intensely in antebellum New York—property.

Its story is not merely that of a neighborhood that “once existed.” It is the story of a deliberate Black project: building a community capable of educating its children, worshiping without surveillance, circulating information, and accumulating wealth—while the surrounding city, and much of the nation, remained invested in slavery, its profits, and its afterlives. Even after New York State ended slavery in 1827, the danger to Black life did not end; it changed form, becoming entangled with kidnapping threats, discriminatory law, and the ever-present risk that freedom could be stolen back by violence or by statute. Weeksville’s builders responded with institutions—durable, community-controlled, and strategically placed.

Today, much of Weeksville’s physical footprint is gone, but the community’s significance has only grown clearer as historians, preservationists, and residents recover the evidence: surviving Hunterfly Road houses, records of schools and newspapers, and the civic infrastructure that positioned Weeksville as both a refuge and a platform.

What follows is a closer look at Weeksville’s accomplishments—economic, religious, educational, and civic—and the contested but compelling evidence of its relationship to the Underground Railroad and broader abolitionist networks. The goal is not reverence without rigor, but clarity: to treat Weeksville not as a sentimental “lost village,” but as a sophisticated Black-built system for survival and advancement in 19th-century New York.

Economic accomplishment: Property as protection, enterprise as strategy and the discipline of self-sufficiency

Weeksville’s economic achievement begins with land—not as metaphor, but as mechanism. In antebellum New York, property ownership was not only a path to stability; it was, for Black men, often a gatekeeping requirement for political participation. Scholarship and public history accounts of Weeksville have emphasized that a significant share of adult Black men there held land, a fact with direct implications for voting rights and civic power. In practice, this meant Weeksville’s economy was never merely about subsistence. It was about leverage—accumulating enough assets to qualify for rights the state otherwise rationed.

The community’s founder, James Weeks, a Black stevedore, and residents built what can be described as an economic ecosystem: households, trades, and services that allowed the village to function with a degree of autonomy unusual for Black life in the period. Accounts of Weeksville describe a settlement that grew to several hundred residents by the mid-19th century and included a range of occupations—farmers and skilled workers, professionals, and community leaders—drawing people from across the Northern states, the South, and the Caribbean. The composition itself mattered: it meant Weeksville was not a single-class enclave, but a layered community where economic mobility could be imagined and, for some, achieved.

Weeksville’s relative geographic position within Brooklyn also shaped its economic possibilities. It existed close enough to the city to access markets and employment, yet far enough—at least initially—to provide insulation from some of the daily harassment and density of Manhattan’s racialized labor economy. That semi-detached location made it possible for residents to cultivate land, build homes, and establish institutions with less immediate interference than Black New Yorkers routinely faced in more central districts. This was not isolation; it was intentional placement.

Economic life in Weeksville also connected to the community’s broader institutional development. The existence of a Black-owned newspaper, The Freedman’s Torchlight, points to both literacy and a consumer base—people with enough stability, interest, and political consciousness to support a publication (even if intermittently) as part of civic life. The newspaper is widely cited as among the early Black newspapers and is associated with Weeksville in archival and educational resources. Print culture is not separate from economics: publishing requires capital, distribution, and an audience that understands itself as a public.

Moreover, Weeksville’s post–Civil War institutions underline the community’s ability to marshal resources toward collective care. Sources describing the community note the presence of an “old age home” (often referenced as the Brooklyn Home for Aged Colored People or related initiatives) and the Howard Colored Orphan Asylum’s ties to Weeksville networks. These are not peripheral details; they reveal the community’s financial and organizational capacity. Care institutions require land, staffing, fundraising, governance, and sustained community buy-in—especially in a period when Black people could not assume reliable access to municipal welfare systems.

Even in the community’s decline as the city expanded, the economic arc remains instructive. Weeksville’s story is, in part, about what happens when a Black-built economy collides with infrastructure, demographic shifts, and development pressures that do not prioritize the continuity of Black place. The erosion of Weeksville’s distinct identity over time did not disprove its earlier success; it demonstrated how vulnerable Black geographies have been to urban transformation.

When Weeksville is reduced to a “hidden gem,” its economic discipline can be missed: the hard calculus of acquiring property to secure rights, building an internal market for services and institutions, and treating self-sufficiency as a collective strategy rather than a private virtue. Weeksville’s economy was not romantic. It was designed.

Religious accomplishment: Churches as sanctuaries, civic engines, and abolitionist infrastructure

In Black community formation, churches are often described as spiritual homes first and civic institutions second. In Weeksville, the two roles were inseparable. Churches helped structure moral life, but they also served as meeting places, mutual-aid hubs, educational partners, and, according to multiple historical accounts and institutional histories, potential conduits for abolitionist activity—including Underground Railroad support.

Weeksville is associated with several historic Black congregations, including Bethel Tabernacle African Methodist Episcopal Church and Berean Missionary Baptist Church, among others cited in historical summaries of the community. The listing of these churches as part of Weeksville’s institutional landscape is significant because Black churches in the 19th century were among the few spaces where Black people could exercise leadership at scale—setting agendas, controlling budgets, and building networks beyond the surveillance of white civic authority.

Berean’s origins, as described in church and local historical resources, emphasize abolitionist-era interracial organizing and social change commitments. These accounts portray early meetings of mixed racial groups, the purchase of land “on the hill” in the area then associated with Weeksville/Carrsville, and the subsequent development of the congregation. Even when one reads such sources with appropriate caution—recognizing that institutional histories can be celebratory—they still reveal how churches frame their own identity: as vehicles for both faith and freedom work.

Religious life also functioned as a stabilizer and a signal. In a period when Black communities were frequently stereotyped as transient or disordered by hostile observers, churches helped establish a visible, disciplined public face. They hosted life-cycle rituals and social services; they cultivated leadership; they built choirs, auxiliaries, and women’s circles that turned belief into work. That infrastructure becomes especially visible in the historical record through affiliated institutions and community partnerships—for example, the support networks described in connection with the Howard Colored Orphan Asylum and the community volunteer labor that sustained it.

Religious institutions were also intimately tied to literacy and political education. Black churches routinely served as sites where community news circulated, where speeches were delivered, where fundraising occurred, and where collective decisions were made. In Weeksville, the broader existence of Black print culture and civic organizations suggests a population used to public argument—an environment in which churches did not merely preach salvation but also participated in shaping a political worldview.

Finally, churches often served as “protective architecture.” In a time when free Black communities were vulnerable to both formal discrimination and informal terror, a church could operate as a community alarm system, a shelter, or a place to coordinate response. The significance of this role becomes sharper when considering the 1863 Draft Riots in Manhattan and the ways Black New Yorkers sought refuge from racial violence; public history resources describe Weeksville as a refuge during that period. A community with churches and community houses has places to receive people, feed them, and integrate them—temporarily or permanently—into a network of care.

To understand Weeksville’s religious accomplishment, then, is to understand institution-building. The churches were not merely remnants of piety. They were early Black civic machines—fundraising bodies, leadership incubators, and, potentially, nodes in a freedom network whose details were often intentionally undocumented.

Educational accomplishment: Schools, literacy, and the production of a Black public

Weeksville’s educational accomplishment is one of its most documented and enduring legacies, in part because education leaves traces: school names, board records, curricula, and buildings that can be identified long after a neighborhood’s street grid changes.

The community is closely associated with “Colored School No. 2,” a segregated school in Brooklyn that is repeatedly referenced in public history and archival education materials. Accounts indicate that the school became connected to the Brooklyn Board of Education in the mid-19th century and that it served generations of Black children. Importantly, historical resources also highlight leadership by notable educators and abolitionists, including Junius C. Morel, who is cited as a principal for decades. These details matter because they show Weeksville’s education system as both local and political: staffed and shaped by Black leaders committed to more than basic instruction.

Education in Weeksville also cannot be separated from civic status. If Weeksville was partly engineered as a community of property owners with political rights, then schools were a way to reproduce that capacity across generations. Literacy and numeracy were essential for economic advancement, but they were also prerequisites for full participation in abolitionist and equal rights movements: reading newspapers, writing petitions, understanding legal changes, and navigating a society that attempted to deny Black competence at every turn.

The presence of The Freedman’s Torchlight reinforces this point. Whether one classifies it as a newspaper in the conventional sense or as a community publication with a particular mission, its existence implies a literate public and a commitment to information. Educational lesson materials from Brooklyn-focused initiatives treat Weeksville’s newspaper as a teaching tool and highlight its role in activism and community learning. The relationship between schooling and print culture is mutually reinforcing: schools produce readers; publications produce the habit of being a public that expects argument, evidence, and debate.

Weeksville’s educational accomplishment also includes the broader idea of “education as activism”—not simply in classrooms, but through community-led historical recovery. The rediscovery of Weeksville in the late 1960s—credited in multiple sources to researchers including James Hurley and Joseph Haynes—became, in its own right, an educational project: teaching Brooklyn to recognize that Black history was not an accessory to the city’s past but a foundational chapter. Institutions that later formed to preserve the Hunterfly Road Houses and interpret the site extended Weeksville’s educational mission into the present, creating tours, curricula, and exhibitions.

The educational story is also visible in how Weeksville is now used as a framework for broader Black studies and public education. Contemporary curricula and community programming position Weeksville as a case study in Black enclave formation, civic life, and resistance—an indication that the community’s educational model is not treated as parochial, but as nationally instructive.

In sum, Weeksville’s education system was not merely about access to schooling in a hostile environment. It was about producing Black citizens—people equipped to own property, organize institutions, defend rights, and narrate their own lives in print and in public.

Civic accomplishment: Voting rights, institutions of care, and Black governance in practice

Weeksville’s civic accomplishment is best understood as governance without a charter. Many communities have churches and businesses; fewer assemble a full civic ecosystem that includes political participation, social services, print culture, and structured responses to crisis. Weeksville did.

One of the most consequential civic facts about Weeksville is the relationship between property and voting. In antebellum New York, Black men faced property requirements for suffrage that did not apply in the same way to white men. That reality transformed landownership into a political strategy. Historical summaries of Weeksville emphasize that many residents owned land—an indicator not only of relative economic success but of intentional civic design. A community of landholding Black men could vote, and a bloc of voters could influence local politics, school governance, and civic negotiations.

Civic life also emerges through Weeksville’s institutions of care. The Howard Colored Orphan Asylum, described by the New York Public Library as having strong ties to the Weeksville community and support from Black churches, illustrates how Weeksville operated as a platform for Black-led social welfare. In a period when Black children—especially those of formerly enslaved families—faced extraordinary vulnerability, the creation and maintenance of an orphan asylum was a civic act: a declaration that Black communities would build their own safety nets when the state would not.

Print culture was another civic instrument. The Freedman’s Torchlight is linked, in multiple accounts, to early Black public discourse in Brooklyn and to organizations associated with Black uplift and post-emancipation debates. Whether the paper’s circulation was wide or narrow, its very production signals political imagination: Weeksville residents understood themselves as part of a broader Black world, connected to emancipation’s aftermath, Reconstruction-era debates, and diaspora questions of migration and institution-building.

Weeksville’s civic function as a refuge during the 1863 Draft Riots adds a crucial dimension: crisis governance. When Manhattan erupted in violent anti-Black riots, public history resources identify Weeksville as a place where Black New Yorkers sought safety. Refuge is not accidental. It requires space, networks, and the capacity to absorb newcomers without collapsing. A community that can shelter families fleeing racial violence demonstrates organizational resilience and an implicit civic confidence: Weeksville was not merely a place to live; it was a place to go when the city turned lethal.

Civic accomplishment is also present in Weeksville’s modern afterlife—the way residents and preservationists fought for recognition, landmark status, and institutional support. The rediscovery and subsequent preservation of the Hunterfly Road Houses became an example of grassroots civic action: research, advocacy, landmarking, fundraising, and educational programming. Contemporary reporting notes that the Weeksville Heritage Center has worked to preserve artifacts and interpret the community’s history, and that it has navigated the realities of funding and municipal support—becoming part of New York City’s Cultural Institutions Group in the 2020s, a structural shift with real implications for resources.

Weeksville, in other words, practiced civic life across two centuries: first as a 19th-century Black community building governance from the ground up, and later as a 20th- and 21st-century fight to ensure that Black-built places are not erased by the city’s selective memory.

Weeksville and the Underground Railroad: Evidence, inference, and the larger abolitionist network

Any honest discussion of the Underground Railroad must begin with a methodological constraint: secrecy was the system. The Underground Railroad relied on discretion, coded communication, and the deliberate absence of records that could incriminate participants. As a result, historians often work with fragments—oral histories, church archives, family stories, and indirect documentation—rather than tidy lists of “official” safe houses.

Weeksville’s relationship to the Underground Railroad is therefore best described through careful language: plausible, supported by multiple strands of evidence and community memory, but unevenly documented in the way modern readers might expect. Several historical accounts and public history summaries argue that Weeksville likely served as a hiding place and may have functioned as a stop—especially after the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 increased the danger to free Black people and self-emancipated fugitives even in Northern states. The logic is not abstract: Weeksville was a free Black settlement with churches and community institutions, positioned within Brooklyn—a borough with strong abolitionist activity and proximity to maritime routes and movement corridors.

One of the clearest institutional claims comes through church histories and related documentation tied to Berean Missionary Baptist Church. Multiple sources describing Berean’s early history state that the church served as a “way station” or “station” on the Underground Railroad. While institutional narratives must be evaluated with critical care, it is notable that this claim appears across different kinds of sources: church “about” pages, organ/history documentation, and local historical commentary. These concordant references suggest that, at minimum, community memory and church identity have long understood Berean’s abolitionist function as central—not incidental—to its mission.

Other accounts speak more broadly: historians “believe” some Weeksville churches functioned as stops. That phrasing matters. It indicates scholarly caution—an acknowledgment that definitive proof is difficult—while still conveying that Weeksville’s institutional landscape fits a recognizable abolitionist pattern. Churches, in particular, were suited to Underground Railroad support because they were already spaces of gathering, they could house visitors under the cover of legitimate meetings, and they operated within networks of trust.

Weeksville’s likely involvement is also strengthened by contextual evidence about the threats free Black communities faced after 1850. Public history accounts emphasize that slavecatchers patrolled Northern states and that Black people—free-born or formerly enslaved—risked kidnapping. In such an environment, a place like Weeksville could serve two overlapping functions: a destination for those who had already fled and needed to disappear into a Black-run community, and a staging ground for further movement. Even if a fugitive did not “stop” in the cinematic sense of hiding under floorboards, the community could still provide vital services: temporary shelter, food, information, introductions to conductors, and the social camouflage of belonging.

Importantly, some contemporary interpreters of Weeksville’s history urge audiences not to reduce anti-slavery work to the Underground Railroad alone. Reporting that includes commentary from Weeksville-connected educators and interpreters emphasizes that abolitionism was a broader ecosystem—petitions, fundraising, lectures, organizing, and political action—of which clandestine transport was only one component. That framing is essential because it keeps the analysis honest: even if every detail of Weeksville’s Underground Railroad role cannot be proven to modern evidentiary standards, Weeksville’s position in abolitionist networks is still legible through its institutions and leadership.

Weeksville’s function as a refuge during the Draft Riots further underscores its role as a safety geography. While the Draft Riots were not the Underground Railroad, the logic of flight and refuge overlaps: when Black people faced existential violence in Manhattan, they sought safety elsewhere, and Weeksville’s networks made that possible. A community that can absorb fleeing families in 1863 is a community that likely possessed the social infrastructure to assist fugitives in earlier decades, when threats of capture and violence were persistent. This is an inference, but it is grounded in how communities operate under recurring threat: people build pathways of protection, and those pathways adapt to different crises.

Thus, Weeksville’s Underground Railroad story should be told in two registers at once. First, in the careful register of evidence: credible accounts describe Weeksville as a hiding place and a likely stop; church histories assert direct participation; historians cite churches as plausible stations. Second, in the broader register of abolitionist capacity: Weeksville’s property ownership, churches, schools, and print culture created a community competent in secrecy, mutual aid, and political coordination—precisely the conditions under which Underground Railroad support could occur.

Weeksville’s most profound contribution may not be any single “stop,” but the creation of a durable Black refuge in a region where freedom was constantly contested.

A brief coda on rediscovery and preservation: why Weeksville had to be found again

Weeksville’s disappearance from popular memory was not inevitable, but it was predictable in a city that repeatedly treats Black-built spaces as expendable. By the mid-20th century, the community’s name had faded for many New Yorkers—until researchers and local advocates pursued the evidence.

Multiple accounts identify the late 1960s as the turning point: research tied to Pratt Institute and collaborators—often naming James Hurley and Joseph Haynes—helped locate surviving structures associated with Weeksville, including what became known as the Hunterfly Road Houses. From there, landmarking and preservation efforts followed, culminating in a modern institutional apparatus that interprets and sustains the site.

Contemporary reporting has emphasized both the promise and the challenge of this work: artifacts that require cataloging, buildings that require maintenance, and a public history mission operating in a city where cultural memory is often determined by budgets. The struggle to preserve Weeksville sits within a national pattern of Black historic sites fighting for recognition and support, a pattern that makes Weeksville’s survival not merely a matter of local pride but of national consequence.