KOLUMN Magazine

By KOLUMN Magazine

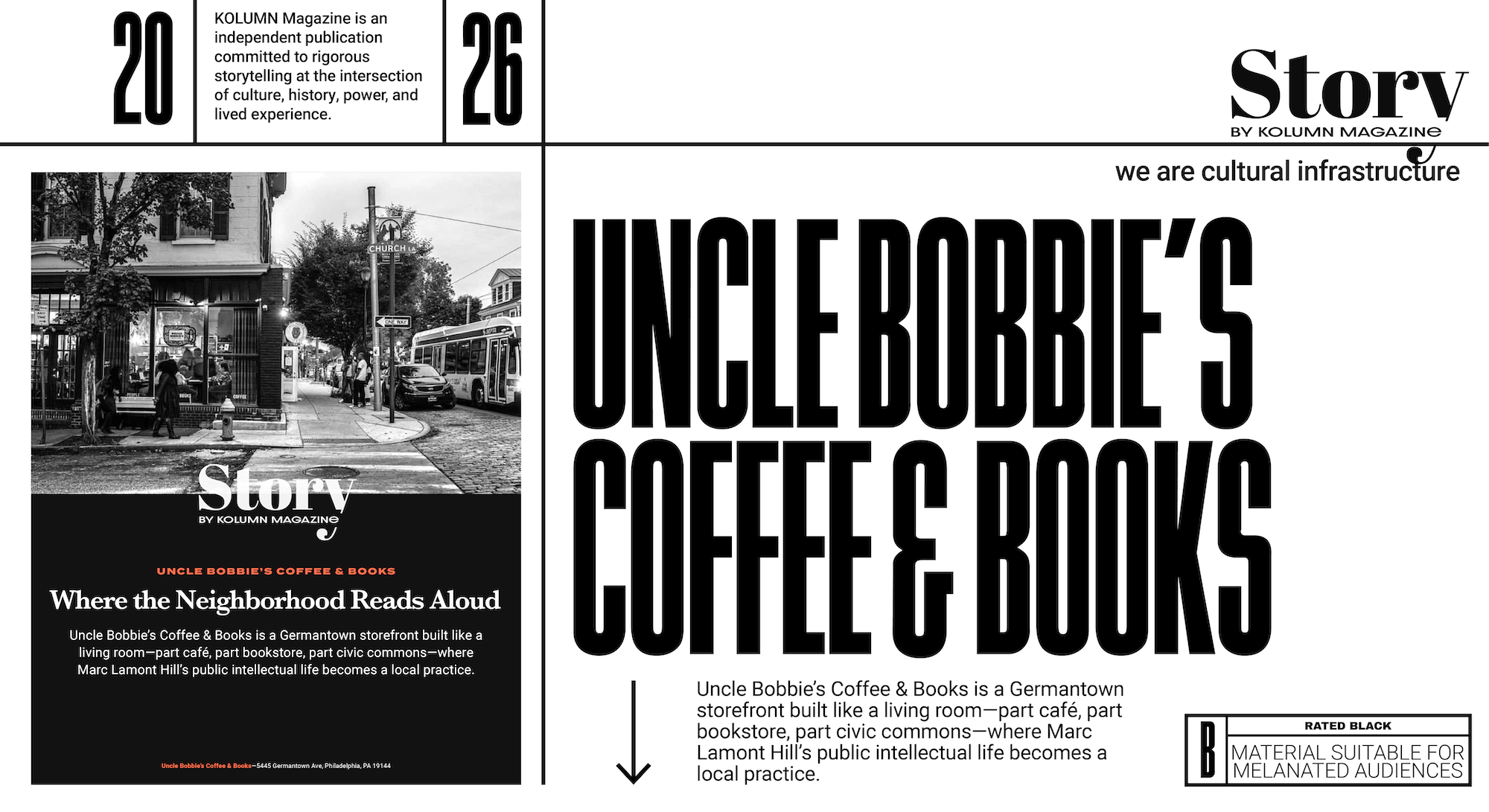

On a typical day in Germantown, the first thing you notice isn’t the coffee—though you can smell it early, the reassuring bitterness of something roasted with intention. It’s the feeling of being allowed to linger. Uncle Bobbie’s Coffee & Books sits along Germantown Avenue with the confidence of a place that knows what it is: a storefront that behaves like a living room, a neighborhood commons, and a literary staging ground. Its own motto—“Cool People. Dope Books. Great Coffee.”—reads like a wink, but it doubles as a thesis statement. This is a business, yes, but also a site of belonging, designed to make undervalued people feel valued.

Uncle Bobbie’s describes itself plainly: a coffee shop and bookstore founded in 2017 by Marc Lamont Hill, created to provide underserved communities with access to books and a space where everyone feels valued. The language is purposefully unflashy—access, underserved, valued—and it’s easy to skim past until you consider how rare it is for a Black-owned independent bookstore-café to speak directly to the emotional and civic dimensions of what it sells. Plenty of places sell books. Fewer promise a space where your presence is not a negotiation.

The shop’s origin story is intimate, even familial. “Uncle Bobbie” is not a branding invention; it is a dedication to the uncle who nurtured Hill’s love of reading, an intergenerational handoff of language and imagination. Philadelphia visitor guides and local coverage describe the shop as taking its name from Hill’s “favorite uncle,” the man who helped form his reading life. In a city where place names often memorialize financiers, generals, or industrialists, Uncle Bobbie’s begins as something else: a private gratitude made public, a family story repurposed as infrastructure.

From the outside, the storefront can look like a simple proposition—coffee and books—one more amenity in a corridor of small businesses. But the inside of Uncle Bobbie’s has been curated with a different kind of ambition: to make it easier for Black people to walk in and feel safe, comfortable, and addressed. Publishers Weekly’s profile of the store framed its mission as building a space where “community, respect, and ideas are in constant conversation,” crediting Hill’s vision and the store’s rapid rise in visibility. Eater Philadelphia went further, describing Uncle Bobbie’s as a business built around restorative justice and community investment—language more common to organizers than retailers. Those are big claims for a bookstore café. The question is whether the shop lives up to them, and what it reveals about Marc Lamont Hill’s long-running preoccupations: literacy, public argument, Black social life, and the spaces that allow all three to breathe.

Marc Lamont Hill’s road to Germantown

To understand why Uncle Bobbie’s exists, it helps to understand the kind of career Marc Lamont Hill built before he ever poured a latte or stocked a shelf.

Hill is often introduced in the shorthand of modern punditry—professor, commentator, author, activist—because he has spent years moving between the academy and mass media, between scholarship and the fast-turning churn of cable news. That mobility is not incidental; it is part of his project. His work, across books and broadcast hits, has generally insisted that ideas do not belong only to universities, and that public discourse—especially about Black life—cannot be left to institutions that do not live with its consequences.

His biography is Philadelphia, from ground-to-sky,: raised in the city, educated at Temple University, later earning graduate degrees at the University of Pennsylvania, then holding faculty positions at institutions including Temple and others over time. The details matter less than what the arc suggests: Hill’s adulthood has been shaped by educational institutions, but also by a skepticism about what those institutions can do alone.

In media, Hill has been a familiar face across outlets and eras—appearing in roles that demanded speed, clarity, and a tolerance for conflict. He has been the subject of public controversy, too, most prominently when CNN ended its relationship with him after his 2018 speech at the United Nations on Israel and Palestine, a moment widely covered and contested in the press. Whether one views that episode as accountability, capitulation, or something more complicated, it underscored a central fact of Hill’s public life: he has long refused to keep his politics tidy for the comfort of mainstream gatekeepers.

That refusal has costs, and Hill’s career offers plenty of examples of how media institutions reward, punish, and reframe Black intellectuals—sometimes within the same news cycle. The Atlantic, for instance, has archived moments that capture the frictions of Hill’s on-air life: confrontations that reveal how quickly Black expertise is asked to perform under hostile conditions. Hill’s public presence has been both an opportunity and a target, a recurring reality for Black commentators who enter arenas that were not designed to treat them gently.

So why open a bookstore-café?

The standard entrepreneurial narrative would say: because it was a good idea, because it filled a niche, because the numbers made sense. Uncle Bobbie’s has never marketed itself like that. Its own self-description foregrounds mission: access, community, a space where everyone feels valued. Philadelphia Magazine’s 2017 reporting on the shop’s opening framed it as a “labor of love” and a tribute to Hill’s uncle—the person who taught him to love the written word—positioning the store as an extension of Hill’s identity rather than a side hustle.

In other words: Uncle Bobbie’s wasn’t merely opened; it was authored.

Local reporting and profiles fill in the practical and emotional logic. Hill is from Germantown, and people close to the store have described the location as a return rather than a relocation—opening a bookstore where he grew up, building in the neighborhood that made him. The store’s general manager, Justin Moore, has emphasized the origin story’s intimacy: Uncle Bobbie as the person who introduced Hill not only to reading, but to Black culture and identity. That distinction matters. For many Black readers, the first books that feel like home are not assigned in school; they are handed down by family, found in church libraries, borrowed from friends, discovered in barbershops and aunties’ living rooms. A shop named for an uncle is a signal that the store understands literacy as relationship.

Hill’s decision also fits within a longer tradition of Black intellectuals building institutions when mainstream ones prove insufficient. Historically, Black newspapers, mutual-aid societies, churches, and bookstores have served as parallel civic structures—places where information circulates, arguments sharpen, and dignity is protected. Uncle Bobbie’s lands squarely in that lineage, even if its aesthetics—bright shelves, café counter, event flyers—feel contemporary.

By 2020, the logic of building a physical community space faced a brutal stress test. The pandemic pushed much of public life online, and bookstores—especially small, independent ones—had to rethink survival. The Washington Post captured what made the disruption so existential for a place like Uncle Bobbie’s: everything about it was designed to be experienced in person—flipping through curated shelves, talking with neighbors over espresso, crowding into free events—until stay-at-home orders forced reinvention.

A physical “third place” is only as strong as the bodies that can safely gather inside it. Uncle Bobbie’s had to translate community into logistics: online sales, shipping, digital programming, and a broader reliance on platforms built to help independents compete. The Washington Post also reported on Bookshop.org as a critical tool for indie stores during that period, noting Uncle Bobbie’s among the shops using it to sell online and keep revenue moving.

And yet: Uncle Bobbie’s endured. Its own social posts and event pages suggest ongoing programming, continuing into recent years. If the store began as an act of local devotion, the pandemic era forced it to become something else as well: a test case in whether a mission-driven Black bookstore-café could survive a period that punished precisely what it offered—proximity.

Uncle Bobbie’s as local and national Black infrastructure

Uncle Bobbie’s is frequently described as “more than” a bookstore. That phrase can be cliché, a marketing tic. In this case, it reflects an observable truth: the store has functioned as an institution of Black public life, both locally in Philadelphia and, increasingly, as a recognizable node in a national ecosystem of Black bookstores and cultural spaces.

Start locally. Germantown is not Center City; it does not rely on convention traffic or tourism as its lifeblood. A shop like Uncle Bobbie’s is, by design, accountable to neighborhood rhythms—school drop-offs, church calendars, block concerns, the daily mathematics of rent and wages. The store’s website makes community programming central to its identity, listing free author talks, workshops, weekly story time for kids, and back-to-school drives as core offerings rather than occasional extras. That matters because free programming is not simply generosity; it is an economic decision. It is the store choosing to invest in the neighborhood as a civic partner, not merely monetize it as a customer base.

The events themselves do cultural work. Author talks are not only promotions; in Black communities they often operate as intergenerational seminars—places where elders, students, activists, and casual readers sit in the same room and debate what a book is asking of them. Workshops and symposiums (which the store and its partners have referenced in public descriptions) expand that function, turning the space into a small-scale continuing education platform. Weekly story time for children, meanwhile, is a quiet intervention: it makes reading communal, embodied, and early. It trains kids to associate books with warmth and attention, not only with tests.

It is also a signal to parents: you do not have to beg an institution to treat your child gently here. You can bring them into a space explicitly designed to value them.

That feeling—of being safe, unprofiled, and unburdened—shows up repeatedly in how Black bookstore advocates describe what “Black bookstore” truly means. A Washington Post opinion column in 2024 quoted the manager of Uncle Bobbie’s describing a “true Black bookstore” as being “about the community that you serve,” about mission, about the books on the shelf, and “about the way… Black people feel safe.” Publishers Weekly’s “Black Bookstore Is More Than a Label” essay similarly used Uncle Bobbie’s as an example of what Black bookstores provide: a place where Black people can walk in and feel comfortable, shedding fears of being profiled, and where the cultural questions asked of them are human rather than suspicious.

In practical terms, Uncle Bobbie’s plays at least four local roles at once:

A literacy institution. Not only by selling books, but by shaping reading habits through children’s programming, curated shelves, and event-based engagement.

A convening space. Free events and workshops make it a de facto community center, with the particular advantage of being organized around ideas rather than bureaucracy.

A social “third place.” The café component is not incidental; it is the mechanism that invites people to stay. The Washington Post noted how central the in-person experience was—talking to neighbors over espresso, browsing slowly—until the pandemic interrupted it.

A neighborhood pride object. Local coverage has emphasized what it means for Germantown to host a widely known Black-owned bookstore-café, and how the community has rallied behind it during pivotal moments.

Those roles are why Uncle Bobbie’s has been repeatedly included in city guides to Black-owned Philadelphia businesses: it is not merely “a place to buy things,” but a place that represents a set of values—community pride, cultural seriousness, and welcome.

Now widen the lens to the national Black community.

Uncle Bobbie’s has become recognizable beyond Philadelphia partly because of Marc Lamont Hill’s profile, but also because it participates in broader national circuits: author tours, publishing ecosystems, online bookselling platforms, and cultural conversations that travel across city lines. Bookshop.org, for example, turned many local bookstores into national vendors during the pandemic, enabling readers anywhere to support independents; Uncle Bobbie’s maintains a presence there consistent with that shift. Its event listings show authors with national reputations—Coretta Scott King Honor–winning writers among them—using the space as a stop on broader literary routes.

In the modern publishing economy, where independent bookstores often serve as the most trusted intermediaries between readers and books, a store like Uncle Bobbie’s does more than retail. It shapes what gets read, who gets platformed, and which communities are treated as core audiences rather than niche markets. Publishers Weekly’s profile pointed to the store’s “meteoric rise” and the visibility that comes with a mission-driven Black indie bookstore gaining momentum.

National attention also arrives in unexpected ways. In late 2024, local reporting noted Uncle Bobbie’s logo appearing in a Netflix series, creating a burst of visibility: an accidental advertisement for Germantown’s cultural infrastructure. The store’s general manager spoke about the impact of being seen on a platform “not a small” one—how it introduced some viewers to the store for the first time and reminded others of a familiar neighborhood anchor. In an era when Black cultural spaces often struggle for sustained capital, even incidental exposure can convert to real revenue—and, just as importantly, to symbolic validation that the space “counts.”

Uncle Bobbie’s national role is also ideological. It is part of a wider re-emergence of Black bookstores as movement-adjacent institutions—places that do not simply sell “racial justice books” during political flashpoints, but maintain year-round commitments to Black thought, Black joy, and Black debate. The post-2020 surge in demand for books about systemic racism created both opportunity and tension: it boosted sales but risked turning Black pain into a seasonal market. Independent Black bookstores have often responded by insisting on deeper, more expansive shelves: not only trauma narratives, but romance, sci-fi, children’s picture books, cookbooks, poetry, history, theology—life in full.

Uncle Bobbie’s, by design, belongs to that insistence. Its existence argues against two tired claims: that bookstores are dying, and that Black people don’t read. The store’s own social language has pushed back on those notions directly. And its popularity—the fact that it has at times discussed the need to grow beyond its existing space—suggests demand that exceeds the stereotypes.

In February 2025, Resolve Philly reported on a GoFundMe campaign framed around helping Uncle Bobbie’s “grow,” referencing the store’s popularity, the constraints of its current footprint, and ambitions to upscale. Whether or not one agrees with crowdfunding as a model for sustaining civic institutions, the moment clarifies what Uncle Bobbie’s has become: not only a shop, but something the public is asked to invest in as shared infrastructure.

That is the real measure of the store’s role in Black communities: people treat it like it belongs to them.

Building the store: Mission, aesthetics, and the politics of curation

If Uncle Bobbie’s were only a café with books on the wall, it would not matter this much. What distinguishes it is curation—what it chooses to place at eye level, what it chooses to platform, what it considers “essential.”

Curation is sometimes misunderstood as taste-making for elites. In Black communities, curation can be a survival skill. It is the process of assembling a counter-canon when mainstream syllabi erase you, when big-box stores understock your writers, when school libraries treat Black history as a February cameo. A Black bookstore’s shelves are an argument about what knowledge should be easy to reach.

Uncle Bobbie’s mission statements emphasize the underserved and the valued. In practice, this has meant building a collection that signals welcome to readers who have learned to expect condescension or suspicion elsewhere. Publishers Weekly’s commentary on Black bookstores used Uncle Bobbie’s as a reference point for that affective labor—comfort, safety, the absence of profiling. That labor is not abstract. It happens in the daily micro-decisions of retail: how staff greet people, how children are treated, whether browsing is protected from surveillance, whether “quiet” is offered as calm rather than enforcement.

The shop’s physical form—bookstore fused with café—also matters. The coffee is not an accessory; it is an engine of presence. A bookstore alone often invites quick transactions. A café invites sitting. Sitting invites conversation. Conversation invites community. That chain is why, as the Washington Post observed, the pandemic disruption was so sharp for Uncle Bobbie’s: the entire design assumed bodies in space, neighbors milling, speakers drawing crowds.

Eater Philadelphia’s framing of the store as organized around restorative justice and community investment captures the deeper logic: Uncle Bobbie’s is trying to be a business that behaves like a neighbor. It does not treat the neighborhood as an extractive market; it treats it as a constituency.

The Marc Lamont Hill brand—and the risk of reducing the store to its founder

A high-profile founder can be both asset and distortion. Marc Lamont Hill’s celebrity makes Uncle Bobbie’s legible to national audiences—he is a known figure in political commentary and Black public discourse—but it can also tempt outsiders to treat the store as a merch extension of a personality rather than a living institution.

The reporting suggests the store has resisted that reduction by building identifiable leadership and identity beyond Hill alone. Profiles regularly reference staff and management—particularly general manager Justin Moore—offering a governance face to the public and reinforcing that the store is not simply Hill at the counter, but an operation with community relationships, curation strategy, and institutional memory.

Uncle Bobbie’s durability—through pandemic disruption and shifting cultural economies—has depended on becoming bigger than any one person, even as Hill’s story remains central to its origin.

Pressure points: The economics of being a “third place” in Black neighborhoods

The romantic story—books, coffee, community—runs into the hard physics of rent, wages, supply chains, and time. “Third places” (spaces that are neither home nor work) are widely recognized as essential to civic life, but they are notoriously hard to sustain in the modern economy, particularly in neighborhoods experiencing disinvestment on one side and gentrification pressure on the other.

Independent bookstores already operate on tight margins; adding café operations introduces additional complexity: equipment costs, health regulations, perishable inventory, and labor models that must remain humane while still being solvent. Uncle Bobbie’s has also leaned into free programming—author talks, workshops, kids’ events, drives—which deepens community impact but does not automatically deepen revenue.

The pandemic illustrated this precarity vividly. As the Washington Post reported, Uncle Bobbie’s had to rethink survival when the in-person experience—browsing, talking, crowding into free events—was suddenly unsafe and, in many places, illegal. The same period accelerated online support structures for indie bookstores, including Bookshop.org, which the Washington Post profiled as a platform handling fulfillment and enabling bookstores to earn a portion of sales without carrying inventory.

This is where Uncle Bobbie’s becomes a case study in a broader question: should community institutions be expected to survive on market logic alone? If a bookstore is functioning as a literacy nonprofit, a neighborhood convening space, and a civic commons, the market may not reward it proportionally. Resolve Philly’s reporting on a growth-related fundraising campaign suggests that even success—popularity, cultural centrality—can create new pressures: a small space becomes a constraint, and scaling up requires capital that small businesses often cannot access easily.

In other words: being beloved is not the same as being funded.

What Uncle Bobbie’s reveals about Black reading, Black debate, and Black joy

At a distance, Black bookstores are sometimes framed as reactive institutions—places that exist because mainstream spaces exclude. That is true, but incomplete. A store like Uncle Bobbie’s also exists because Black communities generate intellectual life that deserves its own venues, not merely a seat at someone else’s table.

The emphasis on author events and story time signals that Uncle Bobbie’s treats reading as social, not solitary. That approach aligns with older Black traditions of communal learning—church study groups, barbershop debate, front-porch storytelling—updated for a bookstore-café era. It also disrupts the lazy stereotype that Black communities don’t read, a claim Uncle Bobbie’s has explicitly rejected in its public messaging.

The store’s national visibility, whether through media profiles or pop-culture appearances, hints at another truth: Black cultural institutions are increasingly forced to prove themselves “viral” to be legible. The Netflix-logo moment, as described in local coverage, brought new eyes precisely because it traveled through a massive platform. Yet the store’s actual value is quieter: children sitting for story time, neighbors talking after work, readers finding a book that doesn’t require translation into whiteness.

Those quiet acts are political. Not in the partisan sense, but in the civic sense: they are about who gets ease, who gets beauty, who gets protected time.

A storefront that behaves like an argument

Uncle Bobbie’s Coffee & Books is not simply a business founded by a famous professor. It is a Philadelphia institution built from a family story and sustained as a public one. Its stated mission—access, value, underserved communities—has been expressed in concrete practices: free events, kids’ programming, community drives, and a curated environment designed to feel safe and human.

Marc Lamont Hill’s journey to opening Uncle Bobbie’s makes sense precisely because it is not a departure from his public life but an extension of it: the same insistence that Black communities deserve rigorous conversation, the same belief that literacy is infrastructure, the same refusal to wait for permission. The store’s endurance through pandemic disruption and its ongoing ambitions for growth suggest that the bet was not naïve—it was accurate.

The deeper lesson may be this: when Black communities build places that honor our own reading lives, those places do not remain small for long. They become stages, sanctuaries, classrooms, and commons—one espresso, one book, one conversation at a time.