KOLUMN Magazine

By KOLUMN Magazine

On January 5, 2026, the Corporation for Public Broadcasting—the modestly sized nonprofit that served as the federal government’s principal conduit for funding public radio and television—voted to dissolve. The decision came after Congress eliminated CPB’s federal funding, pushing the organization into a wind-down that culminated in a formal end.

In the shorthand of contemporary politics, CPB’s dissolution will be framed as a victory or a catastrophe, an overdue correction or an ideological purge. But that framing misses the organization’s most consequential role: CPB functioned as public broadcasting’s stabilizer—an institutional backstop that made it possible for local stations to exist outside the logic of maximum profit, and for national programming to reach families regardless of income, zip code, or the purchasing power that typically governs American media. CPB’s own materials describe it as steward of the government’s investment in public media and the largest single source of funding for public radio, television, and related services.

The closure is not merely administrative. It is an inflection point in the cultural infrastructure that shaped Black childhoods, Black civic life, and Black memory on television and radio—often in ways that were easy to overlook precisely because public media worked best when it felt like a utility: always there, always on, and, for millions of Americans, free.

To understand what is being lost, it helps to be precise about what CPB actually did. CPB was created by the Public Broadcasting Act of 1967. It distributed congressionally appropriated funds to stations and producers, largely through a statutory formula, including Community Service Grants that kept local radio and television operations solvent. A Congressional Research Service report described CPB grants as the “largest single source of funding” for public television and radio stations and for programming development and distribution—and noted that in FY2024, about 10.6% of public television revenue and 6.0% of public radio revenue came from CPB’s Community Service Grants, with far higher dependence for some smaller stations.

Those percentages sound small until you consider what they represent: the difference between maintaining a transmitter and turning it off; between retaining a local reporter and becoming a pure repeater station; between continuing children’s programming and cutting the daytime schedule down to the least expensive hours. CPB was not a single channel. It was the enabling mechanism that supported a system—one that included PBS and NPR but, crucially, also included more than a thousand locally managed stations across the country.

And in Black America, “local” has never been a neutral adjective. Local is where representation meets access: a neighborhood’s ability to see itself on screen, to hear itself on air, to archive its own music and history, to build trust in journalism, and to deliver educational content when commercial media either cannot or will not.

How the closure happened—and why it is different from “another budget fight”

CPB’s dissolution is tied to the elimination of its advance appropriations—funding typically approved on a bipartisan basis for decades—through a rescissions package. CPB has described the rescission as removing more than $1 billion in public media funding and forcing a wind-down that placed hundreds of local stations into crisis. Reporting around the dissolution also points to a broader political campaign against public media, including executive-branch pressure and congressional action that culminated in CPB’s defunding and eventual vote to dissolve.

The legal and procedural context matters because it shapes what “closure” means. The rescission mechanism—rooted in the Impoundment Control Act framework for canceling previously approved spending—was defended by some as a legitimate exercise of fiscal authority, and criticized by others as part of an aggressive approach to withholding or clawing back funds. However one reads the motives, the downstream reality is straightforward: CPB’s structure assumed annual federal appropriations. Without them, CPB could not continue its core function. Its board chose dissolution rather than remaining as a hollowed-out entity.

The consequence is that public broadcasting does not simply “lose money.” It loses a predictable, formula-driven stabilizer that served as the financial base layer for a national network of local stations. Those stations are the last remaining mass-media institutions in many communities that still treat education and civic information as public goods rather than market segments.

What CPB built that Black America engaged—Often without needing to name it

Black audiences have long had a complicated relationship with “mainstream” American media: a steady pattern of extraction, caricature, erasure, and, at times, breakthrough representation that arrives late and leaves early. Public media was never immune to the nation’s racial dynamics, and public broadcasting has had its own documented struggles with diversity and inclusion.

Yet even as the system wrestled with its shortcomings, it also created durable pathways for Black storytelling—particularly in documentary film, public affairs, and children’s programming—because public media’s incentive structure differed. Commercial networks regularly treated Black audiences as either marginal or “niche”; public media, at its best, treated Black life as foundational to the American story it claimed to serve.

One of the most consequential mechanisms was CPB’s support for what became known as the national minority consortia—organizations focused on expanding production and distribution of programming by and about communities historically underserved by public broadcasting. CPB’s own history timeline notes support for national minority consortia beginning in the late 1980s.

Black Public Media—rooted in the National Black Programming Consortium—documents a long record of public television collaborations that helped bring Black documentary work to PBS audiences, along with periods of instability when federal cuts disrupted funding. Those institutions were not abstractions. They were training grounds, commissioning bodies, and distribution channels that helped build careers and preserved narratives: not just celebrity biography, but stories about labor, housing, policing, organizing, migration, music, and the granular truth of everyday Black life.

When CPB disappears, that scaffolding does not vanish in a single day—but it becomes harder to maintain, easier to politicize, and more dependent on the shifting priorities of donors and foundations. Emergency philanthropic efforts have already been mobilized in response to the federal cuts, including commitments aimed at protecting stations serving vulnerable communities. Philanthropy can be life support. It is rarely an operating model for a national system meant to be universal.

Which brings us to the programming that formed the emotional and educational core of Black childhoods for generations: shows that did not simply entertain, but taught literacy, civics, and belonging.

Four titles—Sesame Street, ZOOM, The Electric Company and Reading Rainbow—help explain why CPB’s closure is not only about the future of journalism. It is also about the memory of what public media made possible when it treated children, including Black children, as worthy of care.

Sesame Street: The radical act of making an integrated neighborhood feel ordinary (and making learning feel like play)

Sesame Street premiered in 1969 with a simple-seeming premise: a show that would prepare preschoolers for school. But embedded in its design was a more ambitious wager—one shaped by the civil-rights era’s unresolved questions about access, opportunity, and the nation’s willingness to invest in children who were not affluent and not white.

The “street” was not a fantasy kingdom. It was an urban block populated by adults who looked like the America children actually lived in. In its early years, the show’s human core included an African American couple—Gordon and Susan—portrayed by Matt Robinson and Loretta Long. Their presence was more than representational. It was narrative architecture: a Black family at the center of a mainstream educational program, not presented as a problem to be solved, but as neighbors, mentors, and anchors of stability.

That matters for Black viewers because children’s television is often a first mirror. The earliest messages about who belongs, who teaches, who is trusted, and who is allowed to be gentle are often delivered before a child can name them as messages. Sesame Street’s neighborhood normalized interracial community and Black adult authority in a way that commercial media of the era rarely attempted at scale.

Over time, the show’s cast and cultural references evolved, but its educational ambition remained. The empirical research record—rare for television—suggests Sesame Street had measurable positive effects. A widely cited study associated stronger access to Sesame Street in its early broadcast years with improved school readiness and later educational outcomes, especially for children in disadvantaged contexts. Meta-analyses of Sesame Street research also document learning gains across multiple contexts and international co-productions.

These findings are not simply academic trophies. For Black families, especially those navigating underfunded schools, housing instability, and the long afterlife of segregated opportunity, Sesame Street represented an intervention that did not require tuition, internet service, or a parent’s schedule to align with a private program. It arrived in the living room—through free broadcast signals—because public media was designed to treat access as a mandate.

The show’s cultural significance in Black America is also inseparable from the ecosystem that carried it. Sesame Street may be produced by Sesame Workshop, but it became a national commons through public television distribution—meaning local stations that relied on CPB-backed infrastructure could air it consistently and widely. When policymakers debate CPB in abstract terms, they often miss what Black parents understood intuitively: a show is only as useful as its availability.

And availability is never evenly distributed in America. When the public system weakens, the first losses often occur in places with the least redundancy: smaller markets, rural regions, and working-class communities where commercial stations have little incentive to provide educational programming that does not monetize easily. The broadcast-era genius of Sesame Street was that it did not ask whether the audience could pay. It assumed the audience mattered.

There is another layer to Sesame Street’s resonance in Black life: the show’s insistence on dignity. In a media environment that routinely portrayed Black communities through crime statistics or political panic, Sesame Street offered a different grammar—one in which Black adulthood could be nurturing, humorous, patient, and intellectually serious; one in which Black children were presumed capable of learning, not merely surviving. That presumption can be quietly revolutionary.

It also helped create a generation of shared references across class lines: songs, characters, and segments that became cultural shorthand. Black comedians, musicians, educators, and parents have often spoken of Sesame Street as a baseline—a “we all watched it” program that crossed regional and economic boundaries. The scale of that shared experience depended on the public media system’s reach.

Now consider the closure of CPB not as a cancellation of Sesame Street itself, but as a destabilization of the distribution ecosystem that makes educational content feel universal. If stations close, reduce schedules, or shift programming to cut costs, the practical result is a narrowing of shared civic childhood. In a fragmented media economy, that narrowing is not merely nostalgic. It is structural.

Sesame Street’s legacy in Black America, then, is twofold: it modeled a neighborhood where Black belonging was assumed; and it proved that high-quality early education could be delivered through public infrastructure. The question after CPB is whether the United States still has the will to maintain that kind of infrastructure—especially when the children who benefit most are the ones political rhetoric has historically treated as expendable.

ZOOM: A multiracial, child-led America that treated Black kids as makers, not mascots

If Sesame Street taught preschoolers letters and numbers, ZOOM—which debuted on PBS in 1972—taught something equally important: that children could be producers of culture, not just consumers of it.

Produced by WGBH in Boston, ZOOM ran in its original form through the 1970s and was built around a deceptively radical production choice: kids ran the show. They performed skits, shared jokes, taught simple science experiments, played games, cooked, made short films, and talked with each other about everyday life. Adults were largely absent on-screen, a structural choice that positioned children as authorities within their own world.

For Black American kids, that authority mattered. Children’s television has often relegated Black children to sidekick roles—present for diversity optics, absent when it comes to narrative control. ZOOM’s format and casting choices pushed against that. The show’s multiracial cast and collaborative tone modeled “power-sharing” among children of different races—an explicit cultural counterpoint to the segregationist residue still embedded in American schooling and housing in the 1970s.

The American Archive of Public Broadcasting’s exhibit on ZOOM describes how the show presented inclusiveness as a lived practice—handshakes, shared screen time, and a casualness of interracial friendship that was itself a kind of instruction. Importantly, this was not “after-school special” moralizing. ZOOM made equality feel ordinary by embedding it in the rhythms of play and creativity.

The show’s mail-in culture—kids writing in with ideas, recipes, jokes—created an early participatory media loop. In today’s language, ZOOM looks like a prototype of user-generated content: not optimized for virality, but for community. It taught children that their contributions mattered enough to be broadcast nationally.

That has particular resonance in Black America because Black childhood has often been over-policed and under-protected—treated as older, less innocent, more threatening. A show that granted Black children space to be silly, curious, inventive, and emotionally expressive did cultural work beyond its educational segments. It offered a counter-image to the national gaze.

ZOOM also served as a bridge between two public media commitments: education and representation. Educational content can be technically “universal” while still culturally narrow. ZOOM attempted something harder—making universality feel multiracial without flattening difference into tokenism. Its “ZOOMraps,” informal conversations among kids, addressed topics like family, school, and prejudice in a register that was neither scripted propaganda nor chaotic reality TV.

Critically, ZOOM’s impact cannot be separated from the distribution system that carried it. PBS stations that aired ZOOM were often the same stations that served as community cultural centers—hosting local programs, broadcasting city council hearings, airing documentaries, and offering a public-facing educational schedule that commercial TV abandoned as children’s advertising and cartoons shifted the economics of the medium.

That is why CPB’s dissolution matters even when the shows themselves live on in archives or nostalgia. A healthy public media ecosystem does not merely preserve past programming; it sustains the conditions for future programming that takes similar risks.

There is a reason ZOOM is remembered so vividly by people who were children in the 1970s and early 1980s: it did not talk down to its audience. It treated children as competent peers, and it treated interracial community as something you did, not something you declared. For Black viewers, that was not incidental—it was aspirational and, at times, reparative.

In the present moment, as algorithms sort children into content silos and as the economics of streaming reward either prestige or sheer volume, ZOOM’s model feels almost quaint. But quaintness is not the point. The point is institutional: public media once built a pipeline for child-led, diverse programming that commercial systems had little incentive to produce. CPB helped keep the stations alive that made that pipeline viable.

If CPB’s closure leads to station closures, reductions in children’s programming, or the weakening of local production capacity, the loss is not only financial. It is developmental. It narrows the range of childhood narratives available to Black kids—especially those whose families rely on free broadcast access rather than subscription ecosystems.

ZOOM’s legacy in Black America is therefore both cultural and structural: it modeled a multiracial creative commons, and it depended on a public infrastructure that treated children’s civic imagination as worthy of national investment.

The Electric Company: Decoding power, language, and Black cool on public television

When The Electric Company debuted on PBS in 1971, it did not resemble any children’s educational program that had come before it. Fast-paced, urban, multilingual, visually experimental, and unapologetically “cool,” The Electric Company was designed for a specific audience that American television had largely failed: children who had already reached school age but were struggling to read—disproportionately Black, brown, and working-class students in urban public schools.

If Sesame Street focused on preschool readiness and Reading Rainbow centered reading as pleasure, The Electric Company confronted literacy as power. It treated decoding language not as a neutral academic skill, but as a necessary tool for navigating—and resisting—a world structured by inequality.

The show emerged from research conducted by the Children’s Television Workshop (now Sesame Workshop), which found that many elementary-aged children, particularly in urban districts, were falling behind in reading and disengaging from traditional classroom instruction. The Electric Company responded by meeting those children where they were—linguistically, culturally, and aesthetically.

Its aesthetic was unmistakably Black and urban. The program incorporated funk rhythms, street slang, graffiti-inspired graphics, rapid-fire sketch comedy, and musical interludes that drew directly from the visual and sonic landscape of Black American life in the early 1970s. This was not accidental styling; it was pedagogy. The show’s creators understood that attention is not value-neutral, and that children are more likely to engage with material that reflects their world rather than asking them to abandon it.

For Black children in particular, The Electric Company delivered something rare: intellectual instruction wrapped in cultural affirmation. The cast included a young Morgan Freeman, whose calm authority and expressive voice would later become iconic, and whose presence as a Black adult educator reinforced the show’s legitimacy. Rita Moreno, Luis Avalos, and other performers contributed to a multiracial ensemble that treated diversity not as a theme but as a baseline reality.

Importantly, The Electric Company did not infantilize its audience. It assumed viewers were capable of grasping word structure, phonics, and context through humor, repetition, and narrative play. Segments like “Spider-Man” shorts—where superheroes battled villains using vocabulary clues—recast literacy as an active, even heroic pursuit. For Black boys especially, who were often alienated by reading instruction coded as passive or punitive, this reframing mattered.

The show’s impact on Black America must also be understood structurally. The Electric Company aired nationally on PBS stations sustained by the same CPB-supported funding ecosystem that enabled universal access. That meant a child in a public housing development with no books at home could still encounter daily reinforcement of reading skills. Literacy instruction arrived through broadcast signals—free, consistent, and embedded within entertainment rather than shame.

Educational research has consistently shown that early and middle-childhood literacy gaps are among the most durable predictors of long-term inequality. The Electric Company represented a direct intervention at that fault line. It acknowledged what policy discussions often avoided: that inequitable schooling required compensatory cultural infrastructure, not just reform rhetoric.

Culturally, the show also advanced a critical message about Black intelligence. At a time when mainstream media often portrayed Black communities through crime or pathology, The Electric Company placed Black performers at the center of cognitive labor. They were not comic relief. They were guides, narrators, and problem-solvers. That representation carried symbolic weight for children absorbing messages about who knowledge belongs to.

Like other public television programs, The Electric Company existed because commercial networks had little incentive to produce content for struggling readers. There was no advertising upside in phonics. CPB’s role in sustaining the public broadcasting system ensured that educational value—not profitability—could drive programming decisions. The show’s very existence was a policy outcome.

As CPB dissolves, The Electric Company becomes another example of what is endangered—not necessarily reruns or archival clips, but the conditions that allowed a show to be designed explicitly for marginalized learners at national scale. In today’s fragmented media landscape, literacy programming is either outsourced to underfunded schools or monetized through apps and subscriptions. The broadcast-era assumption that the nation shared responsibility for children’s reading development has eroded.

For Black America, the loss of that assumption carries generational consequences. The Electric Company taught that language unlocks agency—that words are tools, not traps. It treated reading as something to be mastered collectively, not privately struggled through.

In the context of CPB’s closure, The Electric Company stands as a reminder that public media once took seriously the idea that democracy requires readers—and that helping children read was not charity, but civic infrastructure.

Reading Rainbow: Literacy as freedom, imagination as infrastructure

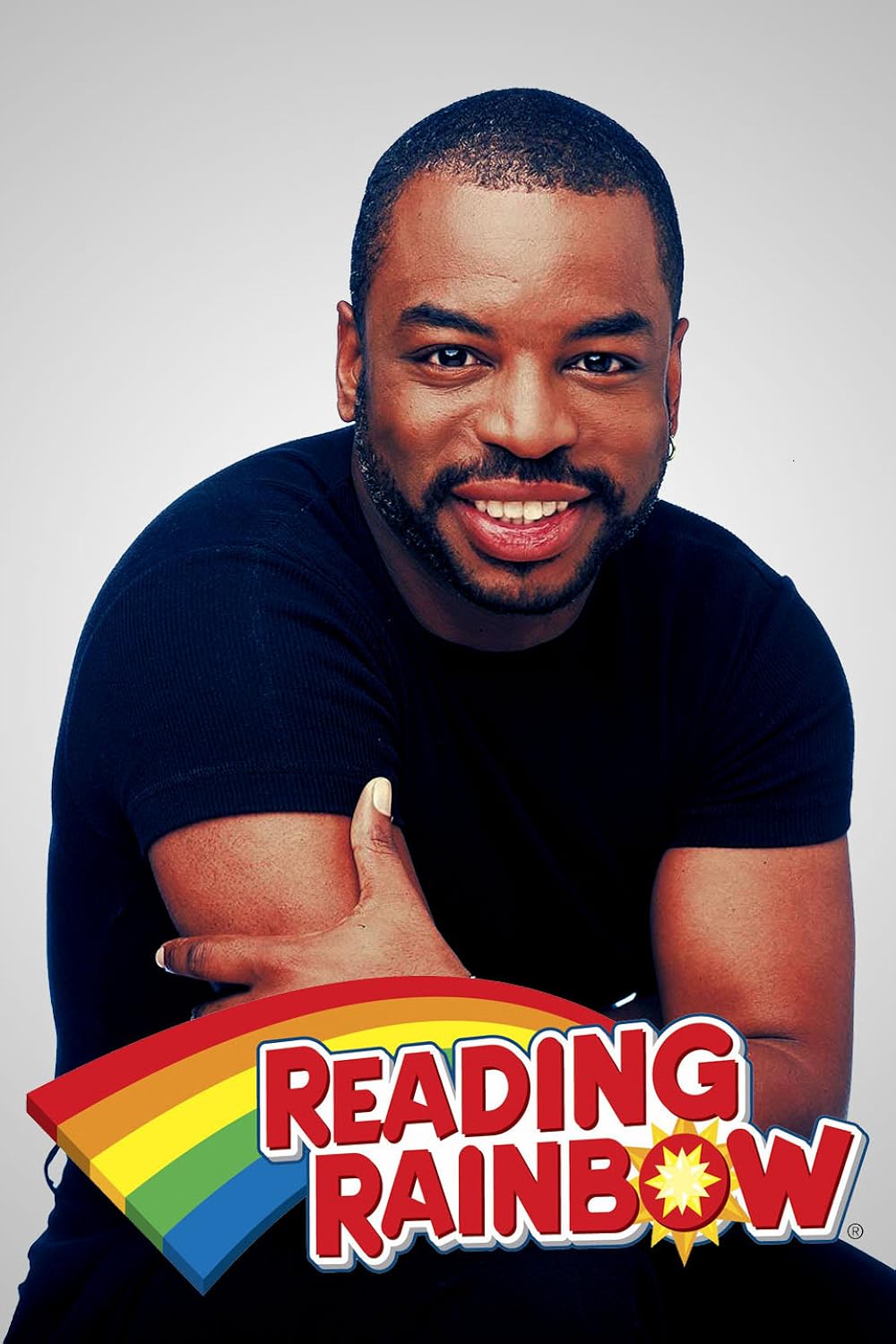

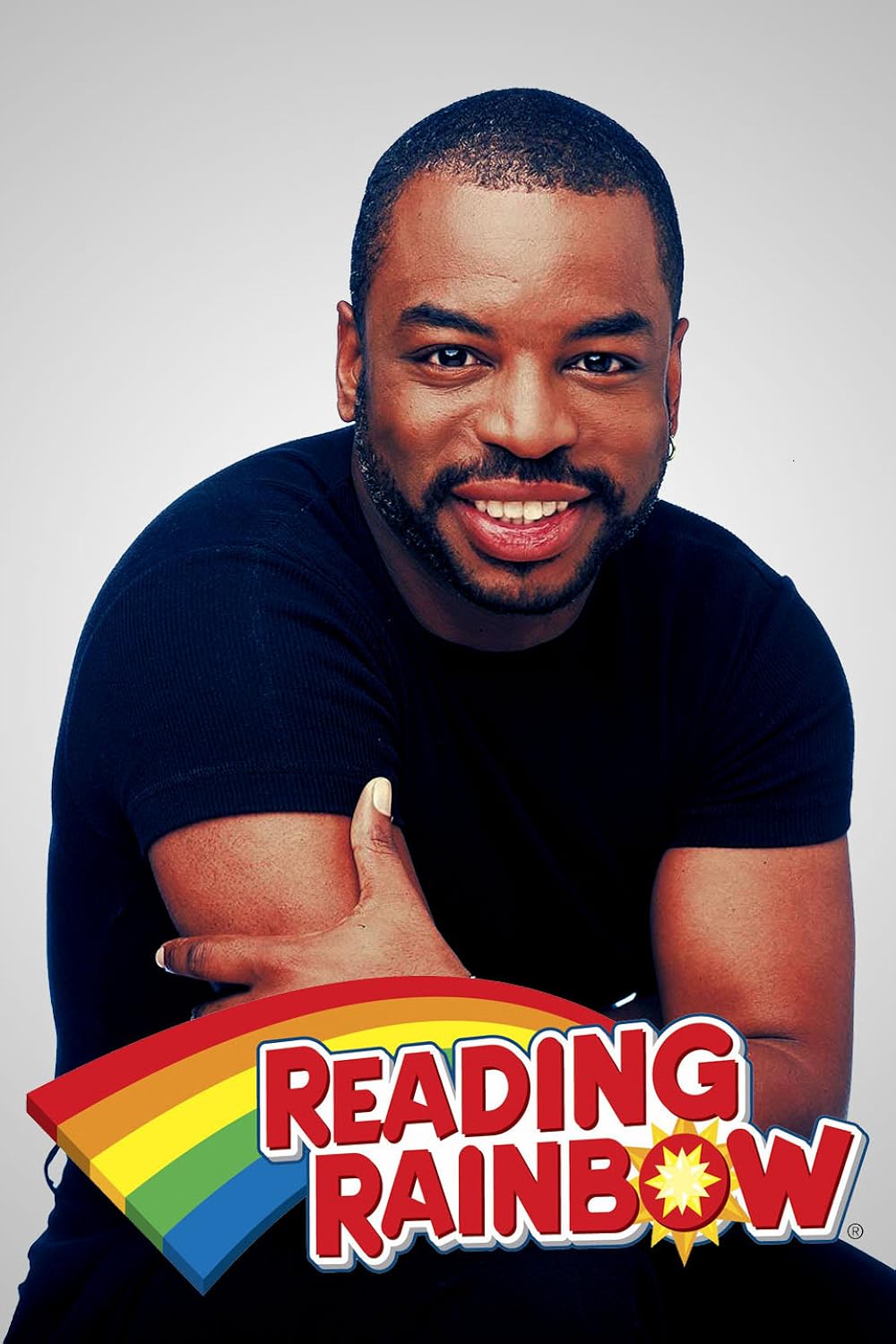

When Reading Rainbow premiered on PBS in 1983, it entered American living rooms with a deceptively modest mission: to encourage children to read. But for Black American families—long positioned at the intersection of educational inequity, cultural erasure, and systemic underinvestment—Reading Rainbow offered something far more consequential. It reframed literacy not as remediation, discipline, or escape, but as joy, agency, and imaginative power.

Hosted by LeVar Burton, already a cultural touchstone from Roots, Reading Rainbow fused storytelling, field trips, and book recommendations into a format that treated children as intellectually curious and emotionally sophisticated. Burton did not lecture. He invited. He did not correct. He accompanied. And critically, he did so as a Black man whose presence alone quietly contradicted centuries of racialized assumptions about authority, intellect, and narration.

The significance of that presence cannot be overstated. In a media environment where Black adults were often absent from children’s educational programming—or present only in narrowly defined roles—Burton functioned as a guide through libraries, museums, science labs, theaters, and neighborhoods. He modeled literacy as lived practice rather than institutional demand. For Black children, especially those navigating under-resourced schools or culturally hostile curricula, Reading Rainbow delivered a counter-message: reading is not something done to you; it is something you do for yourself.

Structurally, Reading Rainbow depended on the same public broadcasting infrastructure that CPB helped sustain. The series was produced by WNED in Buffalo and distributed nationally via PBS—meaning its reach relied on the viability of local public television stations, many of which were financially stabilized through CPB Community Service Grants. In other words, Reading Rainbow was not simply a beloved show; it was an outcome of public policy that treated educational media as a public good rather than a market product.

This distinction matters because literacy programming has rarely been profitable in commercial television. Advertisers prefer spectacle, not stillness; impulse, not reflection. Reading Rainbow thrived precisely because it did not need to chase ratings in the conventional sense. It needed only to exist consistently, accessibly, and free of charge. That consistency—day after day, year after year—created trust. And trust is foundational to learning.

For Black American households, Reading Rainbow often functioned as a supplemental curriculum—especially during summers, after school hours, or in districts where libraries were underfunded or geographically inaccessible. Its book selections frequently centered diverse protagonists and authors, introducing young viewers to stories that reflected their own lives while also expanding their sense of possibility. Crucially, the show never framed Blackness as exceptional or burdensome. It simply included it.

The program’s cultural impact extended beyond childhood. Educators have long cited Reading Rainbow as a gateway for reluctant readers, and numerous Black writers, teachers, and artists have publicly credited the show with shaping their relationship to books. Burton himself became a generational symbol of intellectual warmth—a rare combination of authority and approachability that resonated across class lines.

Research on children’s literacy consistently underscores the importance of early, positive associations with reading—associations grounded in pleasure rather than evaluation. Reading Rainbow operationalized that principle. It did not test comprehension. It celebrated curiosity. For Black children, whose academic performance has too often been surveilled rather than nurtured, that orientation was quietly radical.

The show’s longevity—running for 23 seasons and earning multiple Emmy Awards—masked its fragility. Like much of public media, Reading Rainbow existed within a funding ecosystem that required constant defense. As CPB now dissolves, that ecosystem is materially altered. While Reading Rainbow lives on through reruns, digital platforms, and cultural memory, the conditions that allowed it to flourish are far less secure.

The loss is not only retrospective. Without a robust public broadcasting backstop, the likelihood of future programming that combines literacy, cultural inclusion, and national reach diminishes sharply. Subscription platforms may replicate fragments of Reading Rainbow’s mission, but they cannot replicate its universality. Access mediated by paywalls is not access in the public-media sense.

In Black America, where educational disparities are not abstract but inherited, the erosion of public literacy infrastructure has cumulative consequences. Reading Rainbow taught generations of children that books were portals—to history, to science, to selfhood. CPB helped ensure those portals were open regardless of income.

As policymakers debate budgets and broadcasters scramble for replacement funding, Reading Rainbow stands as evidence of what public media made possible when it treated literacy as liberation and imagination as infrastructure. Its enduring legacy raises an unavoidable question in the wake of CPB’s closure: if reading is fundamental to democracy, who now bears responsibility for making it universally reachable?

The Black public media ecosystem CPB helped underwrite

While Sesame Street, ZOOM, The Electric Company and Reading Rainbow sit at the center of many childhood memories, CPB’s impact on Black America extended far beyond children’s programming. It helped support the station system that carried public affairs shows, cultural reporting, local journalism, and documentary film—the genres that have historically been essential for countering distorted mainstream narratives.

A key part of that ecosystem has been the work of Black Public Media and related consortia, which have documented the ways CPB funding shifts have affected Black production capacity over decades. Even when public broadcasting fell short of its diversity promises, these institutions pushed it—arguing that “public” could not simply mean “available to everyone” while remaining culturally narrow or structurally exclusionary.

It is also worth noting that public broadcasting’s internal diversity debates were not merely moral arguments; they were governance arguments about what public money should produce. CPB commissioned examinations of minority service and diversity in earlier eras, and public media industry reporting has traced how those efforts shaped later initiatives and accountability pressures.

In the immediate wake of federal defunding, Black Public Media leaders warned about impacts and framed the moment as part of a broader political rollback affecting equity and inclusion efforts. Word In Black, reflecting a Black press perspective, argued for restoring and protecting press institutions—including public media—as cornerstones of democracy, particularly amid disinformation pressures that disproportionately harm Black communities.

The throughline is consistent: when public media weakens, the communities that lose the most are those for whom commercial media has never reliably served as a fair narrator.

What comes next: Station survival, archives, and the fight over “public” itself

The risk profile after CPB is uneven. Large, brand-strong stations in major markets may survive through donor bases, underwriting, and philanthropy. Smaller stations—often serving rural regions, smaller cities, and poorer communities—face far steeper odds, because CPB Community Service Grants were designed precisely to keep those outlets alive.

Philanthropy is attempting to fill the gap, including emergency commitments aimed at stations serving vulnerable communities. But philanthropic support often arrives with different constraints than federal support: shorter time horizons, donor preferences, and competitive grantmaking that can unintentionally privilege institutions that already have capacity.

There is also a preservation question. CPB’s dissolution reporting notes efforts to support the American Archive of Public Broadcasting and to preserve CPB’s records through a partnership with the University of Maryland. This matters for Black America because archives are not passive storage; they are battlegrounds over cultural memory. When public institutions preserve footage, audio, and local programming, they preserve evidence of Black life that might otherwise be lost to private rights holders or neglected tapes in station basements.

Finally, there is the civic question: what is a “public” media system supposed to be in an era of abundance and distrust? Some voices argue CPB’s mission is obsolete. But abundance does not equal access, and volume does not equal credibility. For Black communities navigating disinformation, voter suppression narratives, health misinformation, and local news collapse, the value of a trusted, noncommercial outlet is not theoretical. It is practical.

Public media’s promise was never that it would be perfect. The promise was that it would be there—accountable to the public interest rather than the quarterly report; wide enough to reach a child on a couch in a one-bedroom apartment; local enough to cover a school board meeting that no national network will touch; patient enough to let a documentary unfold without commercial breaks or forced outrage.

That promise is what CPB’s dissolution puts at risk.

The immediate story is that CPB has closed. The longer story is that the United States is deciding—again—whether shared civic institutions are worth funding when they are politically inconvenient, and whether Black audiences deserve the same baseline assumption of service that other communities take for granted.

If Sesame Street, ZOOM, The Electric Company and Reading Rainbow taught anything enduring, it is that children can learn a society into being—through repetition, through representation, through the steady reinforcement of belonging. CPB helped build the delivery system for that lesson. Now the lesson is being tested in reverse: what does a society unlearn when it dismantles the institutions that taught it to care?