KOLUMN Magazine

By KOLUMN Magazine

On a shelf crowded with children’s books that promise belonging, The Hair You Were Created With is built around a deceptively radical premise: a Black child’s hair is not a problem to be solved. It is a given—beautiful, intentional, and worthy of love as-is.

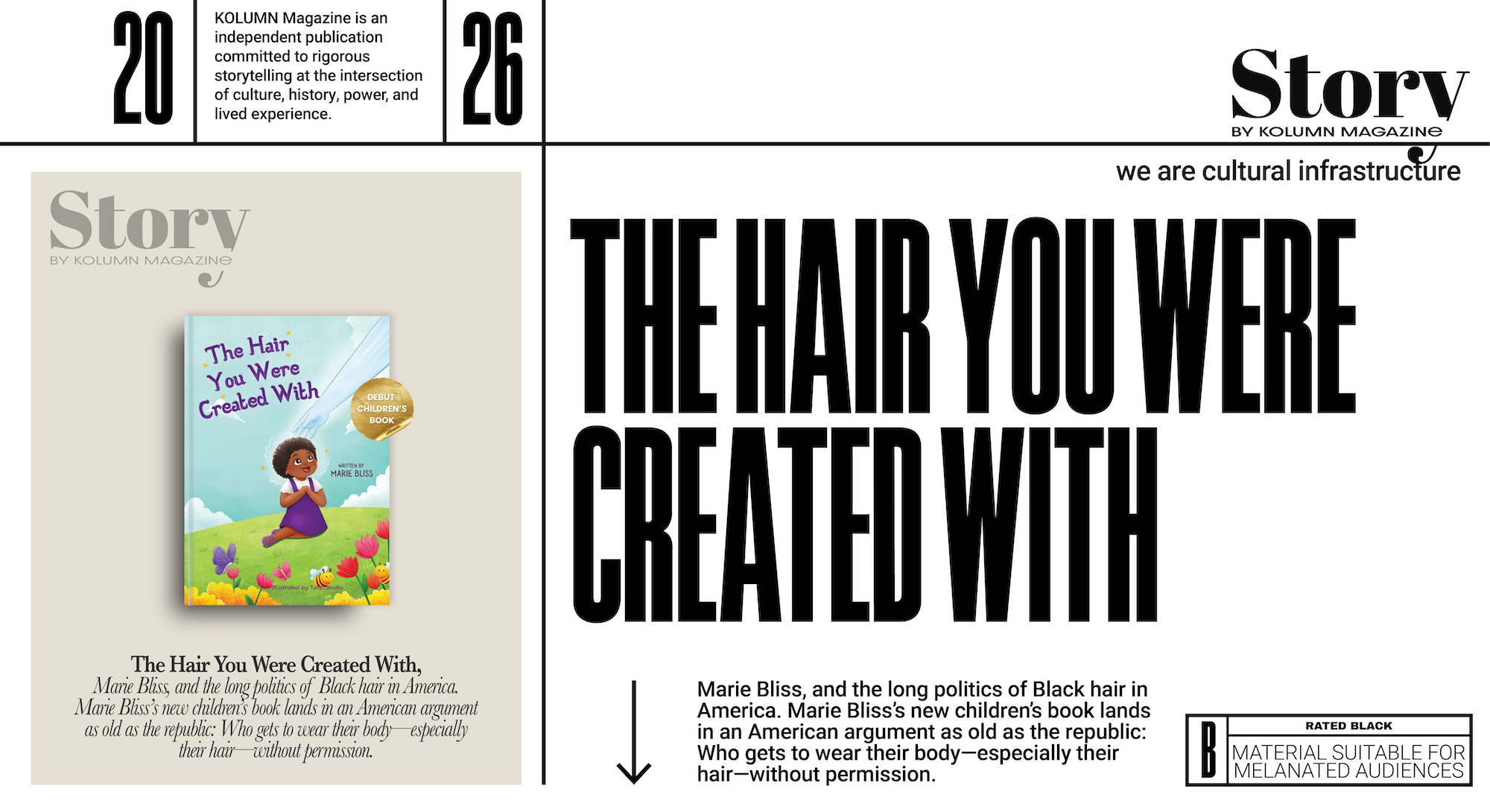

The book’s description reads like a small family liturgy. A girl named Yaa is taught by her parents to embrace “every curl and kink,” and to recognize natural hair as “an extension of God’s creativity.” It is a short, heartwarming narrative aimed at early elementary readers—36 pages, written by debut author Marie Bliss, with publication listed for February 1, 2026.

And yet, for Black Americans, hair is rarely allowed to remain merely tender or merely aesthetic. Hair—its texture, its volume, its cultural styling—has been treated as evidence, as provocation, as workplace “risk,” as schoolyard “distraction,” as military “discipline.” In the United States, Black hair has been surveilled, stigmatized, regulated, and—when it refuses to comply—punished.

That is the context into which Bliss’s children’s book arrives, whether it intends to or not: a nation where the right to wear one’s hair naturally is still debated in policy manuals, litigated in courtrooms, and rewritten in legislatures.

This article is about the book and its author. But it is also about how a story that celebrates curls inevitably brushes against a broader American question: why has Black self-expression—especially through hair—so often been treated as something that must be corrected, contained, or controlled?

A debut book with a clear mission: Affirmation

Marie Bliss’s public biography emphasizes speaking, faith, and law: she is described as a public speaker “who loves the Lord and the beauty of her natural hair,” who pursued legal studies, received the Harmsworth Scholarship, and was called to the Bar of England and Wales in 2023. Her author bio also notes her marriage to international gospel singer Moses Bliss, her work founding “Empyreal Bliss,” and hosting the “Marie Bliss Podcast.”

Those details matter for what The Hair You Were Created With is trying to do. The book’s framing is explicitly devotional—natural hair as “God’s handiwork,” curls as design rather than deviation. It is also plainly pedagogical: a corrective to the early lessons many Black children absorb, often before they have language for it, that their hair is “too much,” “messy,” “unruly,” or in need of transformation.

In the United States, those lessons are not delivered only through peers or media. They are frequently delivered through institutions—schools, employers, athletics, even the armed forces—via “grooming” codes that present themselves as neutral but are often built around white, straight-hair norms.

This is where a children’s book about hair becomes something more than a children’s book. It becomes a counter-script.

Why hair is identity—especially in Black America

To say “hair is political” can sound like sloganizing. But for Black Americans, hair has long functioned as a visible interface between the private self and the public gaze: a place where family tradition, artistry, faith, gender, respectability, and rebellion meet. It is also a place where racism has been practiced with a bureaucrat’s calm: through rules, standards, and penalties.

Historians and cultural critics have traced how Black hair has been treated as a site of social control for centuries—stigmatized, fetishized, regulated. One Atlantic essay, reflecting on the cultural afterlives of hair policing, notes that Black hair has been “surveilled, stigmatized, and even banned from public view” and points to colonial-era rules like Louisiana’s tignon laws as part of that lineage.

The tignon law: When covering Black women’s hair was the point

In 1786, Spanish authorities in colonial Louisiana required Black women to wear a headscarf—tignon—as a marker of social status and control. The policy was meant to constrain how free women of color presented themselves and to reinforce racial hierarchy.

But the cultural lesson endured: Black hair was not treated as neutral. It was treated as power—something to be subdued or concealed.

From “respectability” to resistance, and back again

In the centuries that followed, Black hair became entangled with the politics of “respectability”—the pressure, particularly on Black women, to adhere to white-coded standards of grooming in order to access education, safety, employment, and social legitimacy.

That pressure has had a material history: hot combs, relaxers, wigs, weaves, salon economies, and the industries built around the promise of manageability. But it also has had a psychological history: the internalization of “good hair” as proximity to whiteness; the anxiety of appearing “unprofessional”; the fear that natural texture could trigger punishment.

And then there has been the counter-history: the Afro as both aesthetic and political statement; the natural hair movement as cultural reclamation; locs as spiritual practice, family lineage, and artistic choice.

An Ebony overview of Afro history underscores how natural hair styles have carried political meaning—especially in the 1960s—before also cycling through fashion, commerce, and mainstreaming. The point is not that every hairstyle is always a manifesto. It is that Black hair has routinely been treated as if it were one—by those who wrote the rules.

The institutional instinct: Regulate, restrict, punish

If you want to understand why the CROWN Act movement emerged, you start with an everyday American document: the grooming policy. Its language often looks banal—“neat,” “clean,” “professional,” “appropriate.” But embedded inside those terms is the question of who gets to define normal.

The workplace: “Mutable” identity, the courts said

Modern hair discrimination law in the U.S. has been shaped by a series of cases that narrowed how Title VII (the Civil Rights Act of 1964’s employment discrimination provision) treats race.

In 1981, in Rogers v. American Airlines, a federal court rejected a Black woman’s challenge to a grooming policy that prohibited cornrows. The opinion is widely remembered as an early example of courts treating certain cultural hair practices as outside the core of racial protection.

Decades later, in EEOC v. Catastrophe Management Solutions, the Eleventh Circuit concluded that an employer’s refusal to hire a Black applicant because she wore dreadlocks did not constitute race discrimination under Title VII, reasoning in part through the distinction between “immutable” traits and “mutable” cultural practices. Advocacy organizations including the NAACP Legal Defense Fund criticized the decision as revealing how “facially neutral” grooming rules can enforce white preference.

Those cases helped create the legal reality the CROWN Act movement set out to change: that Black people could be penalized for hairstyles deeply associated with Black identity, and the law might treat that penalty as permissible.

The schools: where identity becomes “dress code”

If the workplace is one front, the public school is another—and sometimes a sharper one, because children are involved, and because school discipline can shape a life.

In Texas, the case of Darryl George—punished by Barbers Hill ISD for wearing locs—became a national symbol of the limits of hair-protection laws when a judge ruled the district did not violate the state’s CROWN Act as written. Reporting emphasized the dispute over whether hair length was covered, even when length is intrinsic to many protective styles.

The story did not end there. It moved through federal court and public appeals, and by 2025, major outlets reported that a federal judge dismissed George’s case against the district, bringing a high-profile chapter of the dispute to a close while broader debates continued. Civil rights organizations responded with letters warning school leaders against race-based hair discrimination and calling out misconceptions about what the law protects.

Texas is not an outlier. It is an illustration: when institutions want to keep policing hair, they often do it through technicalities—length, uniformity, “safety,” “career readiness”—even when the underlying target is cultural expression.

The CROWN Act: A legislative response to a lived reality

The CROWN Act—short for “Creating a Respectful and Open World for Natural Hair”—emerged in 2019 as an explicit attempt to close the gap left by court rulings and uneven local protections. The CROWN Coalition frames it as a ban on race-based hair discrimination—specifically targeting penalties tied to hair texture and protective styles such as braids, locs, twists, and knots.

At the federal level, the bill has been reintroduced repeatedly. In the current Congress, versions titled the “CROWN Act of 2025” have been introduced in both the Senate and the House.

The key policy idea is straightforward: if race discrimination is illegal, then discrimination rooted in racialized hair norms should not be legal either.

How many states protect against hair discrimination?

Counts vary by tracker and by how broadly “CROWN” is defined (some states use different statutory language or executive action). A 2025 legal compliance tracker reported 27 states plus Washington, D.C. as having enacted CROWN laws. The Economic Policy Institute has also tracked state-level adoption and policy effects, framing the laws as strengthening protections for workers and students.

Even where laws exist, cases like Darryl George’s demonstrate a central tension: legislation can name the discrimination, but institutions may still seek interpretive escape hatches. That is why advocates—NAACP LDF among them—continue pushing for clearer, broader protections and consistent enforcement.

The military, the body, and “discipline” as aesthetic policy

Few American institutions demonstrate the “neutrality” argument more starkly than the military, where appearance codes are justified as readiness and uniformity.

Over the last several years, the U.S. Army and Air Force have revised grooming policies to better accommodate women’s hair needs, including styles such as ponytails and authorized braids—changes driven in part by service members’ reports of hair breakage and health issues under earlier rules.

But policy can move in more than one direction. In 2025, Army policy updates emphasized detailed constraints on styles including braids, twists, and locs, with guidance framed around “uniformity,” “discipline,” and “professionalism.” The same year, Army directives reiterated restrictions for male soldiers, explicitly stating that male soldiers are not authorized to wear locs, braids, or twists.

What these rulebooks reveal is not simply the military’s preference for conformity. It is the way institutions routinely convert cultural norms into “standards,” then treat those standards as self-evident.

The cultural contradiction: Celebrated in art, punished in life

The American marketplace is saturated with Black hair aesthetics—locs on runways, braids in music videos, edges in commercials—often celebrated when detached from Black bodies. Meanwhile, Black people themselves continue to face discipline for the same aesthetics in schools, workplaces, and public life.

This contradiction is part of why hair discrimination can feel uniquely destabilizing: it is not just about what you look like. It is about the implied accusation embedded in the rule—your natural self is incompatible with the space you are trying to occupy.

Legal scholars have written about how “neutral” grooming policies can encode racial hierarchy by setting whiteness as the implicit baseline, then treating deviation as disorder. The result is a system where Black people are asked to negotiate access through alteration: change your hair, or accept diminished opportunity.

So where does a children’s book fit in?

This is where The Hair You Were Created With does its quiet work.

The book’s pitch is simple: a Black girl learns to love her curls because they are hers—because they are beautiful and intentional. That message is not new—there is a rich lineage of Black children’s literature affirming hair—but it remains urgent precisely because institutional culture still teaches the opposite lesson in so many places.

A child hears one story at home—your hair is a crown—and another story in public—your hair is a problem. The psychological friction between those narratives can shape identity for years.

In that sense, Bliss’s book is not merely a cultural artifact. It is a protective intervention.

The stakes: What hair discrimination actually does

Hair discrimination is often minimized as superficial—“just hair.” But its consequences are measurable.

Education: Students removed from class, disciplined, or forced into alternative programs lose instruction time and are signaled—publicly—that their identity is deviant. The Darryl George case became national news precisely because it illustrated how quickly hair can become a pipeline into punishment.

Employment: Workers denied jobs or advancement based on hair are denied income, stability, and professional development. The dreadlocks cases show that, historically, employers could frame these decisions as “grooming” rather than “race,” leaving workers without remedy.

Health: Black hair care has also been shaped by social pressure toward chemical alteration, with renewed reporting on risks associated with relaxers and other products tied to beauty norms.

Civic belonging: The deeper harm is the message: some bodies must be modified to qualify as respectable citizens.

This is why advocates describe hair discrimination as a form of systemic racism, not a niche concern.

The future of the fight: Laws, loopholes, and culture shift

The legislative strategy behind the CROWN Act is, in part, an acknowledgment that courts have not consistently protected Black hair under existing civil rights doctrine. It is also an argument that “professionalism” must stop functioning as a coded synonym for whiteness.

But passing laws is not the same as changing institutional reflexes. The next phase of the fight is likely to hinge on three things:

Clarity in statutory language so that institutions cannot hide behind technicalities (the hair-length debate in Texas is a preview).

Enforcement and guidance—school districts, employers, and agencies need explicit compliance expectations, not just abstract prohibitions.

Cultural normalization that makes Black hair unremarkable in spaces that historically treated it as disruptive.

That last point is where literature, media, and family storytelling matter. Policy can prohibit discrimination; culture determines whether discrimination feels socially acceptable.

The quiet power of a public-facing affirmation

Marie Bliss did not write a legal brief. She wrote a children’s story. But the theme—love what grows from you—is a rebuttal to centuries of social messaging.

The book’s title, The Hair You Were Created With, carries an implicit indictment: if hair is created, it is not a defect; if it is given, it is not a threat. In the Black American context, those claims collide with a long record of institutions acting as if Black hair must be explained, contained, or corrected.

It is fitting, then, that a book framed around family love and divine creativity is arriving at a moment when the U.S. Congress is again debating whether hair discrimination should be explicitly unlawful nationwide.

In other words: a picture book is entering the bloodstream of a policy argument.

And maybe that is the point. The most enduring social changes are rarely delivered solely by statutes. They are also delivered by the stories children grow up believing about themselves—before anyone hands them a handbook and calls it “standards.”