By KOLUMN Magazine

Phillis Wheatley’s public story begins the way too many American stories do: with a child taken. Around 1753, she was born somewhere in West Africa—scholars often point to the Senegambia region, present-day Senegal or Gambia—and by 1761 she was in Boston, carried across the Atlantic on a slave ship and sold into a world that had already decided what she could be.

Her private story begins later, in the quiet audacity of learning.

In the Wheatley household—a prominent Boston home—she was renamed for the vessel that transported her and for the family that purchased her. “Phillis” was the ship; “Wheatley” was the owners’ name. The renaming was not merely administrative. It was an assertion of possession in syllables. Yet it is also the name under which she would perform an act the 18th century found nearly impossible to process: she would become a published poet, famous in the colonies and in Britain, while still enslaved.

Wheatley’s achievement is sometimes summarized as a milestone—first Black woman to publish a book of poetry—and the summary is true. But the historical pressure of her life sits in the details: the speed with which she acquired English; the classical and Biblical references she wielded with precision; the way her work moved between sincere faith and strategic address; the blunt fact that she had to prove she had written her poems at all, because many white readers could not imagine Black authorship.

To read Wheatley carefully is to watch a mind navigating an impossible set of constraints: enslaved, female, African-born, and brilliant in a literary culture that used education as both gate and weapon. She wrote in a style that polite society recognized as “legitimate”—neoclassical verse, formal elegies, public odes—because legitimacy was one of the few passports available to her. And she also wrote in that style because she had mastered it. The two facts can coexist without diminishing either.

The making of a prodigy

The Wheatleys—John and Susanna—recognized early that the child they purchased was, by their standards, unusually quick. Accounts from museum and historical sources describe her as small and sickly when she arrived, a condition often noted in the slave trade’s grim arithmetic of pricing and “fitness.” She was bought as a domestic servant for Susanna Wheatley, then educated in the household.

That education remains one of the most debated features of her biography, partly because it is so easy to force it into a fable: benevolent owners “discover” a genius. But the primary fact is simpler and harder: Wheatley learned because she could, because she wanted to, because she made the leap. A household can provide books; it cannot manufacture the interior velocity required to turn those books into art. What she did with what she was given—what she could take—was her own.

She read the Bible. She read the poets of the Anglo-European canon that colonial elites prized. She absorbed the era’s rhetorical habits: invocations to muses, the architecture of couplets, the moralizing cadence of Christian verse, the political language of “liberty” and “virtue.”

This is one of Wheatley’s great ironies and one of her great tools: the same intellectual tradition that many colonists treated as evidence of their superiority became, in her hands, a means of undermining the boundaries they drew around humanity.

By the late 1760s, she was publishing poems. She developed a reputation that moved through Boston and outward across the Atlantic. In an age that treated print as a form of permanence—ink as social proof—her poems did something that legal status refused to do: they made her visible as a mind.

“Did you write this?”: The 1772 authorship test

To understand Wheatley’s era is to understand that her brilliance was not simply admired; it was policed.

In 1772, amid growing attention to her poems, she faced an ordeal that reads now like a tribunal against the very concept of Black intellect: prominent Bostonians examined her to verify that she was, in fact, the author of her work. The result—later published as an attestation—functioned as a kind of credential for white readers: a panel of notable men vouching that an enslaved African girl had written poems they found sophisticated.

The details of that examination have been debated by scholars, but the underlying reality is undisputed: the culture demanded an external stamp of authenticity, because it could not—or would not—grant Wheatley the presumption of authorship. And yet, paradoxically, that demand also shows the threat her work posed. If her poems were self-evidently impossible, there would have been no need to verify anything. The hearing was an attempt to contain the implications of her existence.

The implication was devastatingly straightforward: enslaved Africans were not naturally inferior; they were forcibly denied opportunities. Wheatley was what happened when the denial did not fully hold.

London, 1773: Publication and the transatlantic stage

In 1773, Wheatley traveled to London, accompanied by Nathaniel Wheatley. Sources note that her trip was connected to both her health and the practical reality of publishing: London offered better odds than the colonies for issuing a volume under her name.

That journey is often treated as a kind of climax: an enslaved poet arrives in the imperial capital, meets patrons, and sees her book in print. But it is also an index of how the transatlantic world operated. British abolitionist sentiment—limited and uneven as it was—created a market for Wheatley as proof: proof that Africans could master “civilized” letters, proof that slavery was morally incoherent. At the same time, British elites could praise her while remaining comfortably distant from the plantation system’s brutality, which was more visible in the Caribbean and the American South than in London drawing rooms.

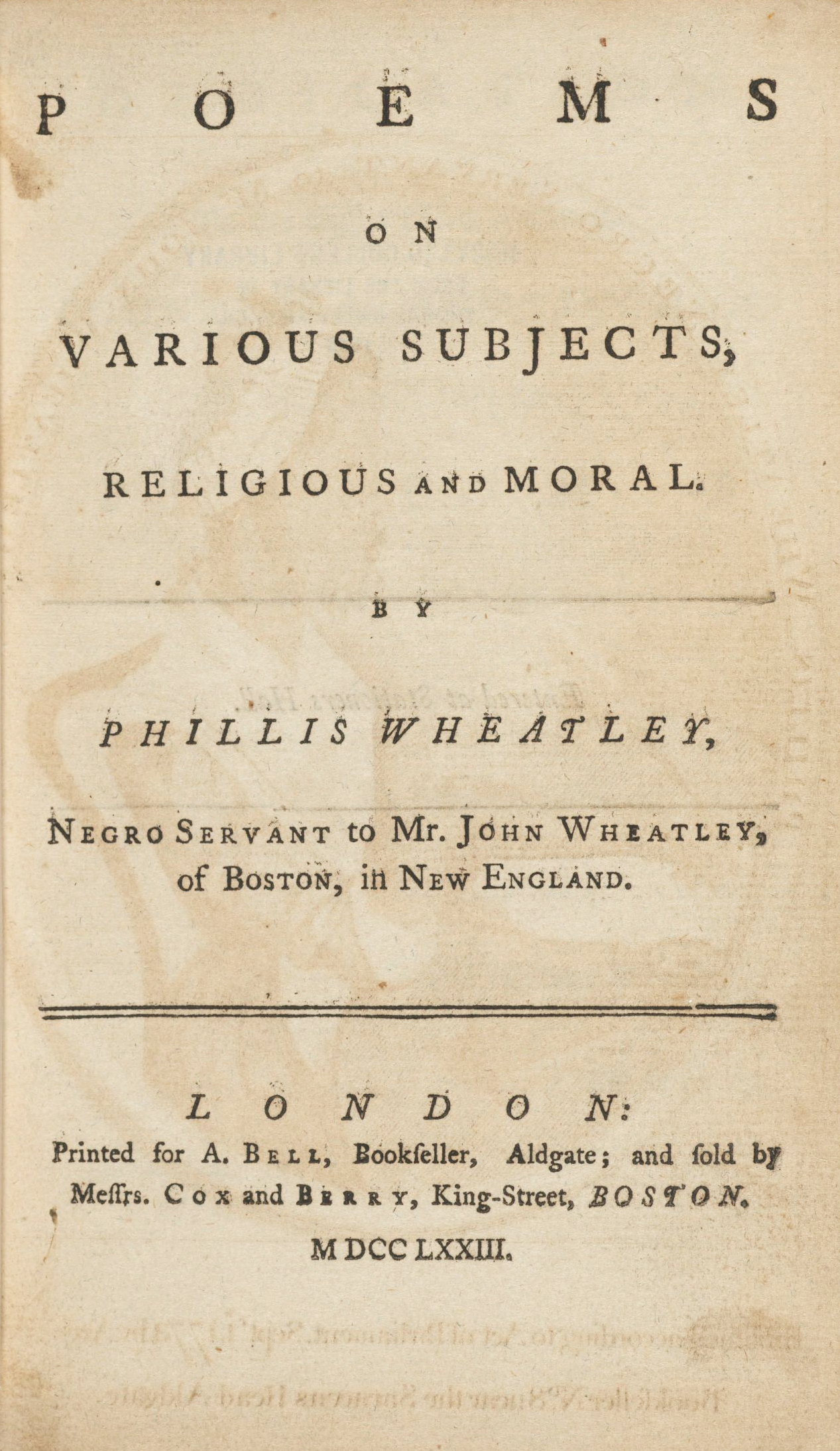

Her book, Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral, appeared in 1773, making her the first person of African descent in the colonies to publish a book of poetry, and among the earliest American women to publish at all.

The volume’s very packaging tells you what the era thought needed to accompany her words: a frontispiece portrait (the famous engraving), a preface, a short biography, and testimonial material affirming authorship. In other words: the poems arrived with paperwork.

In 2023, The Atlantic framed a central truth of this moment with a bluntness Wheatley’s own era rarely allowed: she was “named after a slave ship,” and the naming itself becomes part of the story of how America formed a literary canon while denying the full humanity of the people who could expand it.

What the poems do: Classical form, Christian cosmology, political heat

Wheatley’s poetry is often described as “neoclassical,” but that label can obscure what she actually accomplished. She did not merely imitate the high style of the age; she used it. Her verse is filled with references to Greco-Roman mythology and to Christian theology, the two major symbolic systems that structured much of 18th-century Anglo-American writing.

Her poem “On Being Brought from Africa to America” remains among the most frequently taught. Modern readers often wrestle with its opening lines, which appear to accept the logic of Christian “mercy” in enslavement. Yet the poem also contains a direct rebuke to racist theology: “Remember, Christians, Negros, black as Cain, / May be refin’d, and join th’ angelic train.” It is a compact moral confrontation, delivered in a form polite society recognized.

That tension—between apparent assimilation and pointed correction—runs through the Wheatley archive. She wrote elegies and occasional poems because those were publishable, respectable forms. She also wrote about tyranny and freedom in ways that placed enslaved people inside the moral language of the Revolution, even when the Revolution’s leaders did not place them there.

Take her poem to the Earl of Dartmouth, often read as a meditation on liberty that draws a line—carefully, unmistakably—between colonial resistance to Britain and the violence of slavery. The point is not that Wheatley becomes an 18th-century abolitionist pamphleteer; it is that she learns how to speak in registers her audience cannot easily dismiss, and she uses those registers to widen the frame of what “freedom” is supposed to mean.

Even in poems that appear celebratory, Wheatley’s diction can carry an edge. Her classical allusions—muses, gods, “Columbia”—place America’s emerging identity inside an epic tradition while also highlighting the dissonance between lofty rhetoric and lived reality. She is writing “the nation” into existence and, at the same time, revealing the nation’s contradictions.

The founding fathers as audience—and as evidence

Wheatley’s relationship to the founding era is sometimes flattened into a trivia point: she wrote a poem praising George Washington; Washington wrote back. But the correspondence matters because it demonstrates how her authorship traveled within elite networks and how quickly her talent became political material.

Washington’s letter to Wheatley, dated February 28, 1776, is polite, formal, and—by the standards of the day—recognizant of her literary skill. He thanks her for her poem and engages her as a writer, not merely as a curiosity.

That recognition, however, does not resolve the larger moral contradiction: many of the same leaders who could admire Wheatley lived in a society structured by slavery, and some participated in slaveholding directly. Wheatley becomes, in this sense, a mirror the era both wanted and feared: proof of Black intellect, which could be used to argue for “rights,” and which could also be contained as an exception—an extraordinary individual who did not require systemic change.

Modern institutions continue to treat her as a key interpretive figure for early America. The Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture, for example, has highlighted her life story and her 1773 volume as foundational artifacts in the history of Black letters.

Emancipation, marriage, and the brutal economics of freedom

Wheatley’s emancipation did not arrive as a clean moral awakening but as a tangled sequence of events around publication, patronage, and shifting household realities. Sources commonly note that she was manumitted in the early-to-mid 1770s, after the success surrounding her book.

Freedom, for Wheatley, was not the end of hardship. In the American imagination, emancipation is often treated as a door opening onto possibility. In practice, for many formerly enslaved people, it opened onto precarity: limited employment, racial discrimination, unstable housing, and the constant threat of re-enslavement or legal harassment depending on region and circumstance.

Wheatley married John Peters, a free Black man, in 1778. Accounts suggest he was ambitious and often financially unstable, and Wheatley’s adult life is marked by hardship. She attempted to publish a second volume, but subscribers fell away amid the turmoil of war and the difficulty of sustaining patronage for a Black woman writer in the early republic.

She had children, none of whom survived infancy, and she died in 1784, young—around 31—amid poverty. The arc is stark: international literary fame in youth; economic insecurity in freedom; an early death that left the American republic with a canonical “first” whose life it did not build structures to protect.

This is where modern biography has been especially useful: not to romanticize her suffering, but to place it in the real infrastructure of 18th-century life. Wheatley’s voice did not fade because her talent did; it faded because the conditions for sustaining that talent—money, stability, institutional support—were systematically withheld.

In 2024, the Associated Press reported that historian David Waldstreicher’s biography The Odyssey of Phillis Wheatley won the George Washington Prize, signaling continued scholarly investment in understanding Wheatley not as an isolated prodigy, but as a writer whose life illuminates slavery, independence, and the early republic’s moral economy.

The afterlife: Canon wars, critique, and reclamation

If Wheatley’s life story is a study in constraint, her legacy is a study in argument.

For generations, readers have debated what her work “means.” Some have criticized her for writing within a Christian and classical framework associated with the colonizers and enslavers of her time. Others argue that such critiques impose modern expectations on an 18th-century enslaved writer who had to survive—socially, materially, physically—inside the available idioms of print. A growing body of scholarship emphasizes the subtlety of Wheatley’s critique: the way she could invoke Christian universality to challenge racial hierarchy, or align revolutionary liberty with the condition of the enslaved without announcing herself as a political radical in terms her era would punish.

The Guardian, in a “Poem of the Week” feature on Wheatley’s “An Hymn to Humanity,” notes her blending of Christian and classical myth and treats her work as alive to imaginative self-discovery—language that speaks to the interior dimension of her writing, not only its sociopolitical function.

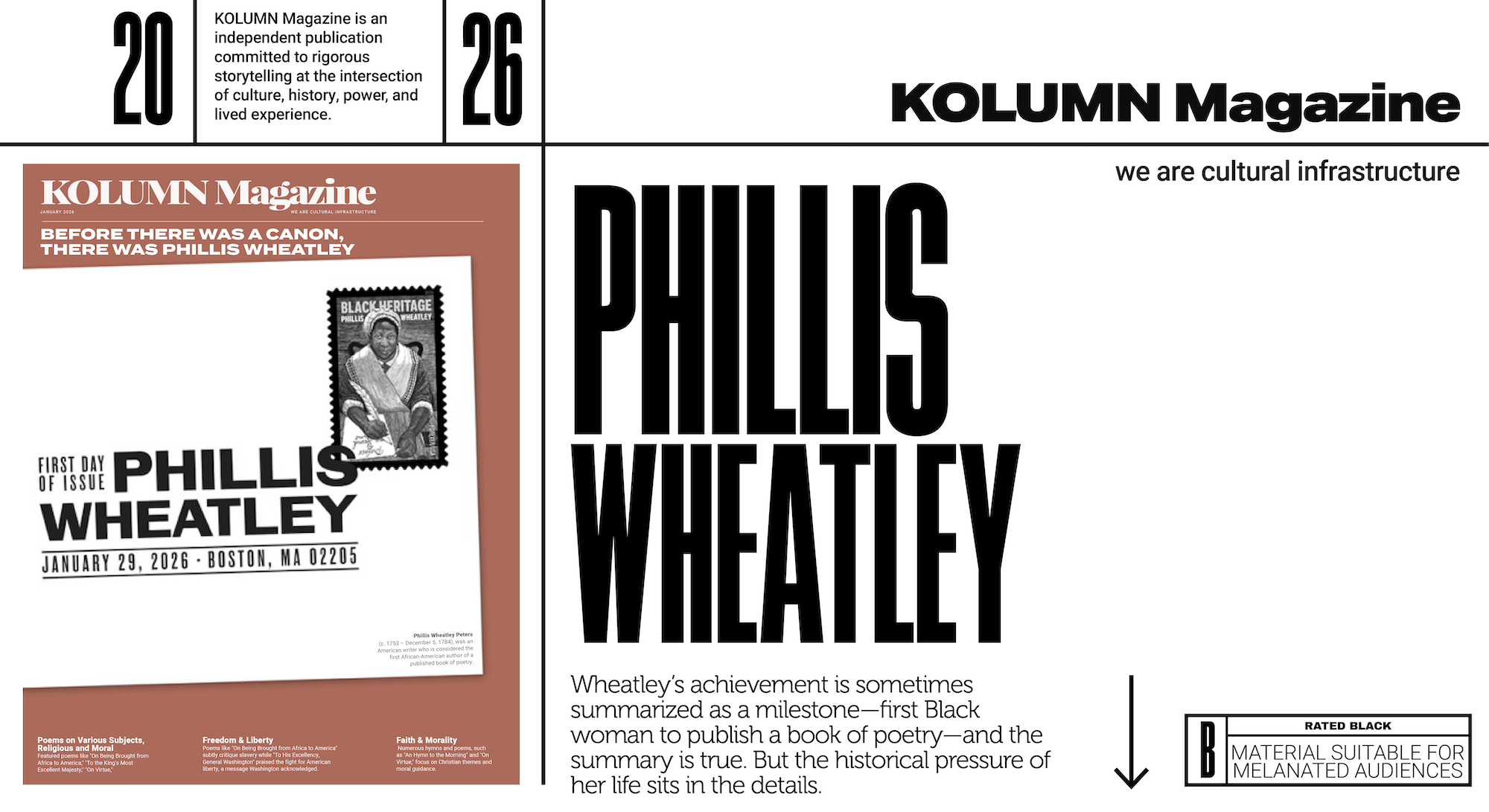

Meanwhile, contemporary cultural outlets continue to circulate Wheatley as a symbol of Black literary “firsts” and of the deep timeline of African American intellectual history. Ebony, for instance, recently linked Wheatley’s legacy to public commemoration through a U.S. Postal Service stamp, framing her story as both historical and urgently present—an emblem of authorship and resistance in a moment when cultural memory is actively contested.

Institutions keep building exhibits and collections around her because Wheatley’s story functions as a kind of early diagnostic for the American project. If the country could celebrate liberty while buying and selling children, what did liberty mean? If the culture could admire a Black poet while doubting she wrote her own lines, what did “reason” mean? If a Black woman could become famous in print while still legally property, what did “personhood” mean?

Wheatley did not merely participate in American literature. She exposed its founding contradictions—and expanded its possibilities.

The journalist’s problem: How to write her without using her

There is a recurring temptation, when telling Wheatley’s story, to treat her primarily as evidence: evidence of Black genius, evidence of slavery’s brutality, evidence of the Revolution’s hypocrisy. She is all of those things. But she is also a person who made craft choices.

She chose, as far as her conditions allowed, to pursue mastery. She chose the discipline of meter and the public stance of the occasional poem. She chose, repeatedly, to address audiences that could harm her and to do it in a voice that demanded respect. Even her most debated lines—those that appear to accept Christian conversion as “mercy”—can be read as part of a complex negotiation: how to speak to Christian readers who held power, while leaving room inside the poem for an indictment of racist scorn.

To write about Wheatley with integrity requires holding multiple truths at once:

She was an enslaved African child in a brutal transatlantic system.

She became, through extraordinary intellect and relentless application, a published poet whose work circulated internationally.

She was subjected to a culture that demanded she be authenticated by white authority.

Her freedom did not protect her from poverty, grief, and social abandonment.

Her poems contain both accommodation to the era’s expectations and—often—strategic moral challenge.

Wheatley’s life is not a neat parable about uplift. It is an early American story told from inside the fissure: between the nation’s stated ideals and its practiced violence; between Christian universality and racial caste; between the “republic of letters” and the marketplace that decided who could enter it.

Coda: What the Nation Finally Put in the Mail

In 2023, more than two centuries after her death, the United States government performed a small but symbolically dense act of recognition. The United States Postal Service announced the release of a commemorative stamp honoring Phillis Wheatley, formally placing her image and name into the daily circulation of American life.

The USPS announcement framed Wheatley as “the first African American woman to publish a book of poetry,” emphasizing her transatlantic literary achievement, her mastery of classical verse, and the historical barriers she overcame as an enslaved Black woman in colonial America. The stamp—designed in warm tones and based on the iconic 1773 frontispiece engraving—depicts Wheatley seated, pen in hand, head slightly inclined, mid-thought. It is a posture of intellect rather than spectacle, deliberation rather than performance.

That choice matters.

For most of her life, Wheatley’s mind had to be verified, defended, and authenticated by others. Her authorship was subjected to examination; her humanity debated; her freedom conditional. To appear on a U.S. postage stamp—an object that assumes legitimacy, authorship, and national belonging without explanation—is to receive, however belatedly, what her era withheld: presumption.

Yet the stamp also carries the weight of historical irony. Wheatley did not live to see the United States stabilize, let alone expand its definition of citizenship to include people like her. She died poor, her second book unpublished, her fame exhausted long before her genius was. The nation that now honors her once required sworn statements to believe she could write.

This is the unresolved tension the stamp cannot smooth over. Commemoration is not repair; recognition is not restitution. But it is a public admission—printed by the state—that Phillis Wheatley belongs not at the margins of American literature, but at its beginning.

The stamp’s release also signals something quieter and more consequential: Wheatley is no longer invoked only as a “first,” a curiosity, or a moral test case. She is increasingly read as a writer—strategic, constrained, devout, ambitious—who understood the dangers of saying too much too plainly and the costs of saying too little. Her work survives not because it is uncomplicated, but because it is precise.

To place her on an envelope is to let her travel again—this time without chains, without affidavits, without permission. It is an acknowledgment that the American story she complicated has finally caught up to the fact of her authorship.

What remains radical about Phillis Wheatley is not only that she wrote under impossible conditions. It is that, centuries later, the country still measures itself against the questions her life made unavoidable: Who is believed? Who is preserved? And how long does it take a nation to recognize the genius it once required proof to see?