KOLUMN Magazine

By KOLUMN Magazine

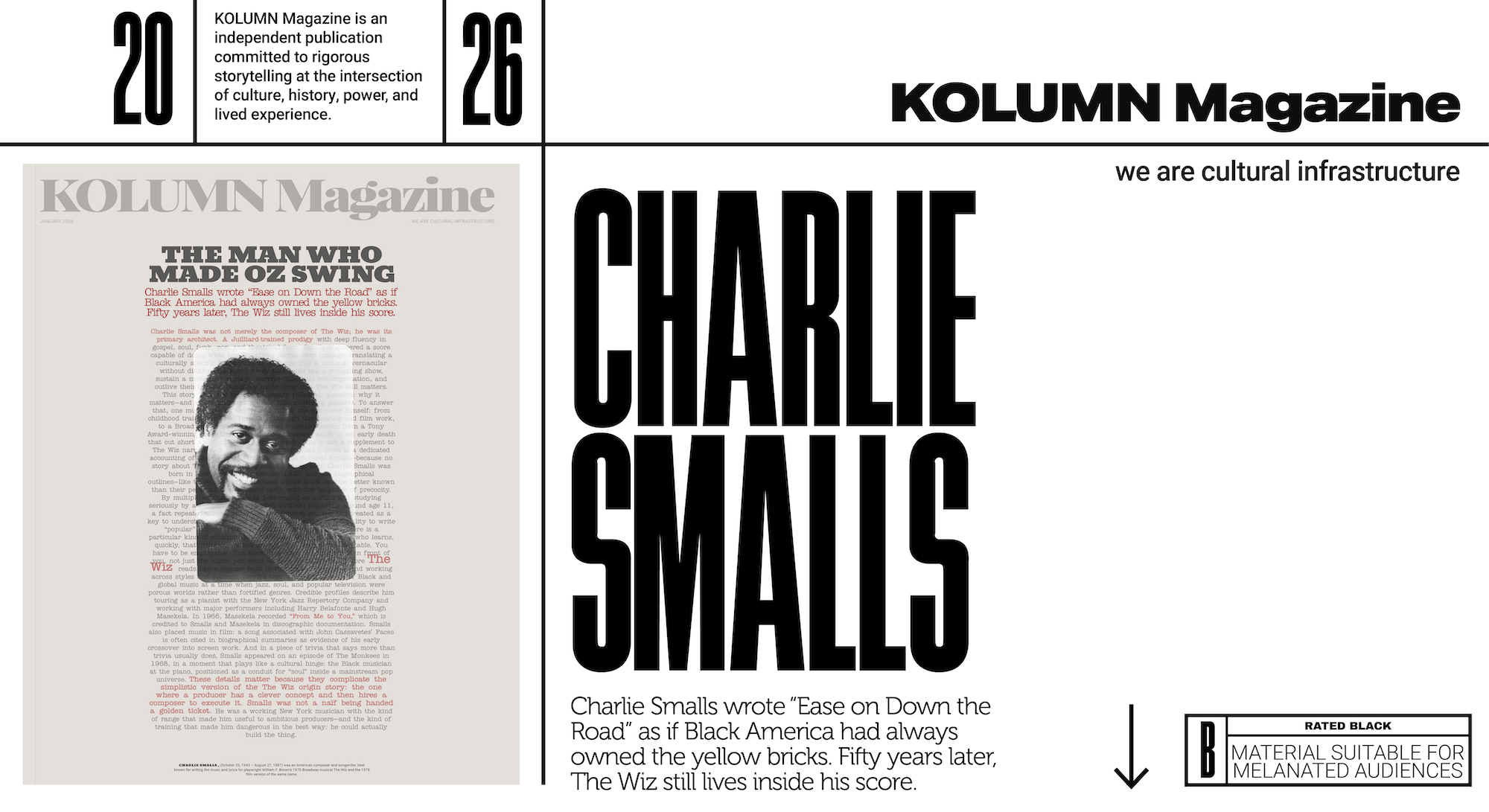

In January (2026), KOLUMN Magazine returned to The Wiz with a clear-eyed proposition: that the musical’s endurance—its stubborn, joyful refusal to fade—was not merely a matter of nostalgia, casting, or revival economics, but of authorship. The essay, “Ease on Down the Road—Again,” argued that The Wiz continues to resonate because it speaks fluently in Black emotional grammar: collective movement, sanctified optimism, humor as survival, and joy as a discipline rather than an accident. It traced how the show, decades after its Broadway premiere and long after its uneven film reception, still functions as a communal text—passed between generations not as a relic, but as living instruction.

Yet even that assessment stopped short of its most unavoidable conclusion.

Because The Wiz cannot be adequately understood—historically, musically, or culturally—without naming the person who made that grammar audible. Without centering the composer whose work did not simply accompany the show’s vision, but authored it.

This is the point at which The Wiz story fractures if left unattended: the music that made Oz move, rejoice, testify, and remember is often praised in abstraction while its composer, Charlie Smalls, remains curiously peripheral in the public narrative. His songs are invoked as atmosphere, his melodies treated as inevitabilities, his score praised as a collective triumph—without sustained attention to the individual intelligence that shaped it.

Broadway history has long favored spectacle over composition, and Black musical authorship has too often been flattened into collaboration without hierarchy. In the case of The Wiz, this has produced a familiar imbalance: producers are remembered, directors are mythologized, performers are canonized, arrangers are debated—but the composer whose music made the show legible, marketable, and durable is rarely granted full narrative authority.

This article exists to correct that imbalance.

Charlie Smalls was not merely the composer of The Wiz; he was its primary architect. A Juilliard-trained prodigy with deep fluency in gospel, soul, funk, pop, and theatrical form, Smalls engineered a score capable of doing what few Broadway scores ever manage: translating a culturally specific Black musical language into a national vernacular without dilution. He wrote songs that could sell a struggling show, sustain a movement onstage, survive cinematic reinterpretation, and outlive their creator.

Our story made clear that The Wiz still matters. This story asks the harder, necessary follow-up question: why it matters—and whose authorship made that mattering possible.

To answer that, one must leave Oz briefly and follow the composer himself: from childhood training in New York City, through jazz touring and film work, to a Broadway gamble that reshaped musical theater; from a Tony Award–winning score that entered the American canon, to an early death that cut short a still-unfolding body of work.

This is not a supplement to The Wiz narrative. It is its missing center.

What follows is a dedicated accounting of Charlie Smalls’ life, craft, and cultural impact—because no story about The Wiz can finally stand without him.

A prodigy in a city that makes prodigies pay rent

Charlie Smalls was born in New York City in October 1943, and the biographical outlines—like those of many musicians whose work became better known than their personal stories—begin early, with the language of precocity. By multiple accounts, he was performing as a child and studying seriously by adolescence. He attended Juilliard beginning around age 11, a fact repeated across archival and reference sources and treated as a key to understanding both his technical command and his ability to write “popular” music that never collapses into cheapness.

There is a particular kind of musician New York can produce: someone who learns, quickly, that virtuosity is not enough. You have to be adaptable. You have to be employable. You have to be able to play the gig in front of you, not just the music you want to play. Smalls’ career before The Wiz reads like a résumé built in that tradition—touring and working across styles and settings, moving through the ecosystem of Black and global music at a time when jazz, soul, and popular television were porous worlds rather than fortified genres.

Credible profiles describe him touring as a pianist with the New York Jazz Repertory Company and working with major performers including Harry Belafonte and Hugh Masekela. In 1966, Masekela recorded “From Me to You,” which is credited to Smalls and Masekela in discographic documentation. Smalls also placed music in film: a song associated with John Cassavetes’ Faces is often cited in biographical summaries as evidence of his early crossover into screen work. And in a piece of trivia that says more than trivia usually does, Smalls appeared on an episode of The Monkees in 1968, in a moment that plays like a cultural hinge: the Black musician at the piano, positioned as a conduit for “soul” inside a mainstream pop universe.

These details matter because they complicate the simplistic version of the The Wiz origin story: the one where a producer has a clever concept and then hires a composer to execute it. Smalls was not a naïf being handed a golden ticket. He was a working New York musician with the kind of range that made him useful to ambitious producers—and the kind of training that made him dangerous in the best way: he could actually build the thing.

The Wiz before it was The Wiz

The most durable The Wiz legend is that it almost didn’t happen. The show opened to mixed response; it needed cash; it needed clarity; it needed marketing; it needed a reason for the public to believe. In the theater version of American capitalism, belief is financing.

Ken Harper, a radio professional turned producer, has been chronicled as relentless—someone who talked up the show with missionary persistence, looking for money, allies, and legitimacy. Playbill’s archival reporting on the show’s early precariousness emphasizes Harper’s hustle and the moment he finally found a connection that mattered—leading to investment that helped keep the production alive. Scholarship and trade histories also highlight that Harper selected Oz partly because the underlying Baum material was in the public domain, lowering rights barriers for an ambitious reinvention.

What is often understated in the popular retelling is that, when Harper went looking for backers, he did not go empty-handed. He had a book (William F. Brown) and a set of songs—Smalls’ songs—substantial enough to be presented as proof of concept. In other words: the show’s survival depended, early on, on Smalls’ ability to write music that could persuade people who had not yet seen the staging, who did not yet know the cast, who were evaluating a Black reinterpretation of a canonical American story through the cold lens of risk.

This is the first major argument for treating Smalls as more than “the composer.” His work functioned as collateral.

How Smalls gave Oz soul

The most reductive description of The Wiz is that it puts soul music into The Wizard of Oz. It is true, as licensing descriptions still note, that the show’s sound draws on gospel, soul, rock, and related Black popular forms. But the achievement is not simply stylistic substitution. Smalls built character through idiom.

Consider what “Ease on Down the Road” does dramaturgically. As a Broadway number, it behaves like a classic “travel” song—movement made musical, characters bonding through rhythm. But its language and groove also reposition the story’s emotional posture. In many Oz adaptations, the road is something like a test: the long moral pathway toward knowledge. Smalls makes it something else: a communal practice. You do not trudge alone; you ease together. The verb is the point. It implies technique—an embodied way of moving through difficulty. The message is motivational, but not abstract: the song is literally about how to proceed.

Or consider “Home.” The song is often treated as the show’s emotional apex, and it is—yet it’s also an argument about what kind of longing Black performance is permitted to express on the American stage. “Home” is not nostalgia for an uncomplicated past. It is a negotiation between desire and reality: an insistence that belonging is not merely geographic but spiritual and social. That thematic weight is one reason the song keeps appearing in auditions and televised tributes. It is an “I want” song that refuses childishness.

Smalls’ gift was that he could load these ideas into forms that feel inevitable—songs audiences think they’ve always known, even when they are hearing them for the first time.

The show’s very subtitle—“The Super Soul Musical ‘Wonderful Wizard of Oz’”—announces a branding strategy, but the score delivers something more precise than branding. It offers a Black aesthetic logic in which sanctified harmony, street humor, and pop hooks are not competing impulses but compatible tools.

That compatibility is not accidental. It’s compositional intelligence: Smalls’ training meeting his cultural ear.

Collaboration without erasure: The Vandross question and the Broadway reality

One reason authorship gets messy in musical theater is that Broadway is collaborative by design. The Wiz is no exception. While Smalls is credited with music and lyrics, other contributors and arrangers are part of the show’s documented history, and later versions and recordings reflect additional musical hands. Reference summaries of the musical list collaborators like Luther Vandross and others in connection with specific songs and musical contributions.

But collaboration is not the same as dilution. Smalls’ voice remains coherent across the score, and that coherence is what made the show’s musical identity so resilient.

A 1979 Washington Post review—written in the context of a production at the National—contains an especially revealing line: it characterizes the Smalls/Vandross score as “underrated,” and suggests one reason may be the way Quincy Jones “padded and discofied” it for the film. Even if you disagree with the reviewer’s tone, the observation points to a real phenomenon: the film adaptation’s sound, shaped by Jones’ sensibilities and the late-1970s commercial environment, can blur the public’s perception of Smalls’ original compositional intent.

This is why it matters to separate Smalls’ authorship from later orchestration choices without turning the story into a feud. Smalls wrote the songs; Broadway and Hollywood rearranged the clothing.

The Wiz as a commercial lesson: When a song becomes a marketing plan

Most Broadway shows would love to believe they became hits solely because they were good. The Wiz became a hit because its goodness was made audible to people who didn’t yet know it.

Multiple retrospective accounts emphasize a now-famous marketing moment: a commercial featuring the cast performing “Ease on Down the Road,” which helped the show find its audience. The implication is not that the ad “saved” a weak show. It’s that the ad amplified what was already the show’s strongest asset: a song that could sell the experience in under a minute.

This, too, is part of Smalls’ legacy. He wrote music that could function as a Broadway hook without sacrificing integrity. Not every composer can do that. Many can write one kind of number brilliantly—either a theater song or a radio song—but not both at once. Smalls could.

And when the show finally caught, it caught hard. The original Broadway production went on to win major awards, including Best Musical, and Smalls himself won the Tony Award for Original Musical Score.

Awards do not equal greatness, but they do document the industry’s recognition: Broadway, at least for that moment, had to say out loud what audiences were already singing.

Broadway as a racial proving ground—and why Smalls’ score mattered to that politics

The story of The Wiz is often told as a breakthrough narrative: an all-Black cast and Black creative vision achieving mainstream Broadway success in the 1970s, alongside a small cluster of other works that expanded the commercial idea of what could be a Broadway “event.”

But breakthroughs are never purely artistic. They are political. They are economic. They are about who gets to be lavish, who gets to be funny without being dismissed, who gets to be universal without being whitened.

Smalls’ score is central to that politics because it offered a Black sonic vocabulary as the default—not as seasoning. It asked audiences to meet the show where it lived: in gospel cadences, funk propulsion, blues feeling, and pop clarity. Licensing and historical summaries repeatedly describe the score in those terms, and the durability of the music has proven the bet correct.

The point was not simply representation. It was authority.

The film: When Smalls’ Oz met Quincy Jones’ Hollywood

In 1978, The Wiz became a big-budget film adaptation directed by Sidney Lumet, with Quincy Jones overseeing the film’s musical treatment and orchestration approach, and a cast that made the project feel like cultural coronation. The film’s existence has sometimes complicated the stage show’s reputation, because the movie’s critical reception has been historically mixed even as its music and iconography remain beloved.

Here is the key distinction: Smalls’ songs remain the spine, but the film’s sound world is filtered through late-1970s Hollywood and the commercial logic of a Quincy Jones production—bigger, glossier, sometimes more disco-forward than the stage score’s original theatrical balance. That tension shows up in contemporary and retrospective commentary, including the Washington Post’s pointed observation about the score being “discofied” for the film.

A fair reading is not that Jones “ruined” Smalls. It’s that Jones translated Smalls for cinema, and translation always changes the original.

What is most impressive is how often Smalls’ writing survives those changes. The melody remains. The emotional architecture remains. The songs still land, even when dressed differently.

The archives: Where Smalls’ authorship becomes physical

One of the most concrete indicators of a composer’s importance is not streaming counts or revival announcements—it is archival preservation: the decision that a body of work is not simply entertainment but historical material.

The New York Public Library’s archives include a dedicated collection related to Smalls’ Wiz materials, documenting the score and its context, and noting the circumstances of his death. The same biographical chain of sources also notes that Wiz materials were donated to the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in the years after his death, reinforcing the idea that Smalls’ work belongs not just to Broadway history but to Black cultural history.

This is an important corrective to the tendency to treat theater music as ephemeral. Smalls’ papers—his notes, his orchestrations, his working documents—tell a different story: a craftsperson at work, making choices that shaped what audiences felt.

Death in Belgium, and the musical that never got finished

Smalls died in 1987, in Belgium, during emergency surgery related to a burst or ruptured appendix, according to multiple accounts including archival notes and period reporting. He was 43.

There is always something brutal about the early death of a composer whose best-known work is associated with joy. It forces a reconsideration of the relationship between the life and the art. The art sounds immortal; the life ends in the middle.

Accounts of his death often include a detail that feels like an unfinished sentence: he was working on a new musical at the time. The specifics of that project vary in summaries, but the common point remains: Smalls was still composing, still building, still moving.

This matters because it disrupts the idea of Smalls as a “one-hit” Broadway figure. The Wiz may be the monument, but it was not the end of his musical ambition.

The long afterlife: Revivals, rediscovery, and the next generation learning his songs

A show’s revival history is one way culture confesses what it cannot let go of. The Wiz has returned repeatedly in different forms and contexts—regional, touring, international, televised—and each return is also a return to Smalls’ score.

In the 21st century, commentary around The Wiz increasingly frames the show as an “ode to Black joy,” a piece whose brightness is not escapism but cultural assertion. In 2006, The Guardian described the original as notable for its all-Black cast and its period influence, placing it in conversation with other Oz narratives arriving on international stages. In 2015, televised attention (The Wiz Live!) helped reintroduce the material to audiences who had not grown up with the original production, reinforcing how readily the songs convert to new performers and new media ecosystems.

More recently, the Broadway-bound revival cycle of the mid-2020s brought The Wiz back into mainstream theater news, with coverage emphasizing that new audiences would be “discovering” these songs again—language that implicitly recognizes Smalls’ music as the enduring lure.

What’s striking about these revivals is how often they center on sound even when the production discourse is about visuals. Reviews can complain about sets, projections, or budget impressions—but the songs keep escaping the critique. Even skeptical notices frequently concede the power of the musical numbers and the cast’s ability to ride them.

This is what it means to write repertory-level music: the score can outlast the staging.

Why Smalls still feels contemporary

To talk about Charlie Smalls as a “composer of his era” is accurate but insufficient. The deeper truth is that he solved a problem that remains current: how to make Black musical language legible as American mainstream without sanding off its specificity.

He did it through compositional strategy:

Melodic memorability without simplification. Smalls writes melodies that lodge quickly, but they are not dull. They carry turns—unexpected emotional pivots—that reward repeat listening.

Rhythmic authority. The songs know where the beat lives, and they respect dance as narrative, not decoration.

Lyric directness with vernacular intelligence. Smalls’ writing can be plainspoken without being thin; it uses accessible language to deliver layered emotional messaging.

Genre fluency as dramaturgy. Gospel, soul, funk, pop—these are not just “styles” applied to scenes. They become the scenes’ meaning.

This is the place where Smalls’ training—Juilliard discipline, professional touring experience, fluency across Black popular forms—turns into a singular authorial signature.

The argument you can make, now, about authorship

Broadway histories often treat composers as part of a team. Film histories often treat composers as subordinate to directors. Black cultural histories often have to do both at once while also contending with the long tradition of Black authorship being minimized or attributed elsewhere.

Charlie Smalls’ case invites a cleaner claim: The Wiz endures because its score is built to endure.

This does not diminish the show’s other geniuses. Geoffrey Holder’s visual imagination mattered. George Faison’s choreography mattered. The performers mattered. Ken Harper’s production persistence mattered. The film’s Quincy Jones treatment mattered—sometimes contentiously, often glamorously, always loudly.

But if you want the simplest test of authorship, you can use the one Broadway itself relies on: what survives when everything else changes?

A cast changes. A director changes. A set changes. A production concept changes. A projection budget changes. A cultural moment changes.

“Ease on Down the Road” stays. “Home” stays. “Everybody Rejoice” stays.

That is composition doing what composition is supposed to do: carrying meaning across time.

Coda: The score as a kind of citizenship

When the Library of Congress places a recording on the National Recording Registry, it’s not merely praising it. It is declaring the work part of the nation’s official sonic heritage. The selection of The Wiz’s original cast album functions, in that sense, like a ceremonial acknowledgment that Smalls and his collaborators authored something America has decided it cannot afford to lose.

For Black musical theater, that is not small.

It means that an Oz imagined through Black cultural logic—through gospel-inflected resilience, through funk and joy as survival strategies, through a road you “ease” down together—has been admitted into the archive where the country stores the stories it tells about itself.

Charlie Smalls did that with notes, with lyrics, with harmonic choices that treated Black sound not as accessory but as foundation.

He made Oz swing. He made Oz testify. He made Oz rejoice.

And then, long before he could fully cash in on what he’d built, he died far from Broadway, in a hospital in Belgium, the kind of ending that feels cruelly out of character for music that insists on brightness.

The songs didn’t follow him there. They stayed behind—on stages, in speakers, in voices that keep rediscovering what he already knew: joy is not a detour from the story. It is the story.