KOLUMN Magazine

By KOLUMN Magazine

If you want to read Tremé, don’t start with a map. Start with a façade.

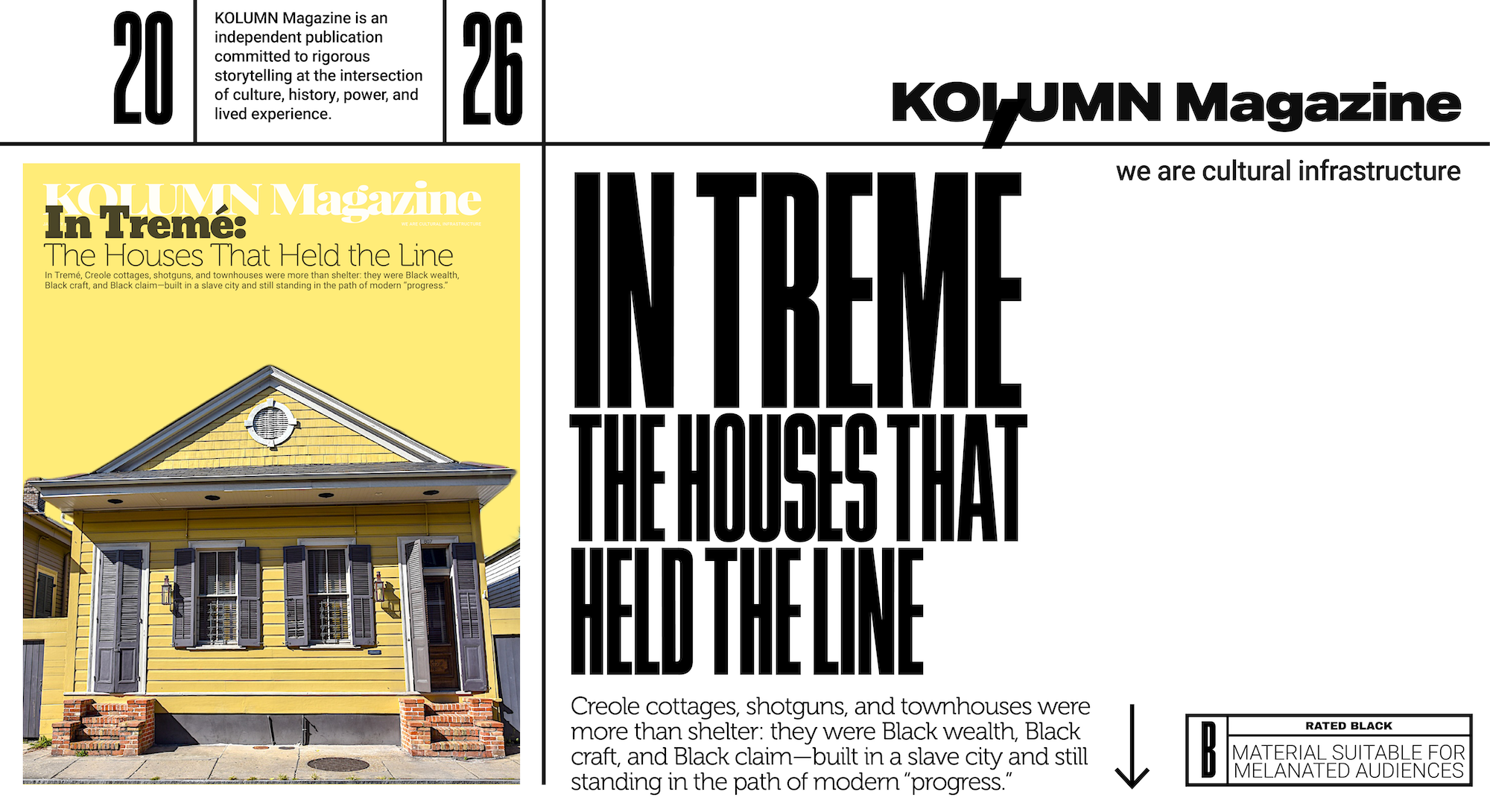

In the early morning, when the light is angled and the neighborhood is quiet enough to hear your own footsteps, Tremé’s buildings show their arguments. A low Creole cottage sits close to the sidewalk, roofline running parallel to the street, its proportions compact but deliberate. Down the block, a shotgun house holds its ground like a narrow sentence—one room wide, stretched long, doors aligned in a straight line that seems to invite breeze as much as passage. Around a corner, a townhouse rises with the confidence of brick and height, the kind of structure that signals capital, not improvisation.

In most American cities, domestic architecture is treated as background: pretty, utilitarian, sometimes quaint. In Tremé—one of the nation’s oldest Black neighborhoods—architecture is not background. It is evidence. Evidence of Black property ownership in a slave society; evidence of skilled Black labor—free and enslaved—shaping the built environment; evidence of cultural continuity from Africa and the Caribbean expressed in plan, porch, ventilation, and craft; evidence, too, of what happens when infrastructure and policy decide a neighborhood’s value can be measured by how quickly other people can pass through it.

The Tremé Historic District summary produced by New Orleans’ Historic District Landmarks Commission (HDLC) reads like a catalog of the neighborhood’s architectural range: Creole cottages, shotguns, and townhouses dominate, with notable early Creole cottages dating to the 1830s and larger-scale townhouses from the 1840s; later decades saw many double shotguns built in the 1880s and 1890s. In one compact paragraph, it sketches a chronology of form—how a community built and rebuilt itself across generations, adapting to climate, codes, economics, and shifting social realities.

But the deeper question—the question Tremé’s buildings insist you ask—is: who made these forms, and what did those forms make possible for Black New Orleans?

Architecture as citizenship in a city built on bondage

New Orleans is often described as exceptional—French and Spanish colonial influence, a significant population of free people of color, a cultural mélange that doesn’t fit neatly into the Anglo-American template. The risk in that telling is that “exceptional” becomes a euphemism for “less brutal.” It wasn’t. New Orleans was a slave city. That is the baseline reality against which Tremé’s early built environment should be understood.

And yet: in the early 19th century, free people of color in New Orleans managed to build wealth and community through real estate and construction. That wasn’t accidental. It was strategy—one of the few strategies available. Owning property was a way of claiming permanence in a society that preferred Black life to be temporary, moveable, dependent.

The story of Jean-Louis Dolliole makes that point with unusual clarity. Dolliole—a free man of color—was a builder and architect associated with Creole cottages and Creole townhouses, and he is described in historical scholarship as a leader in the early development of the Faubourg Tremé area. That detail matters because it reframes Tremé’s architecture as not merely “influenced by” Black Americans, but in part authored by them—designed, financed, and executed through Black agency under constraint.

Architectural Digest’s reporting on free Black architects in New Orleans places Dolliole and the Soulié family in a lineage of gens de couleur libres whose work helped shape iconic local forms—Creole cottages and townhouses among them—while emphasizing how these builders blended French, Spanish, African, and Caribbean influences into a Gulf Coast vernacular. The built environment, in other words, is not simply a record of stylistic trends. It is a record of cultural transmission and survival.

When you walk Tremé with that understanding, the neighborhood’s domestic architecture begins to look less like “housing stock” and more like civic infrastructure. These were structures that anchored kin networks, supported small enterprise, housed mutual-aid organizing, and provided the spatial conditions for the social life—porch talk, music practice, intergenerational caregiving—that made Black community durable.

The Creole cottage: Compact form, expansive lineage

The Creole cottage is often explained as a climate solution: low profile, thick walls or raised floors depending on variant, roof pitches that shed heavy rain, and openings positioned to encourage air flow. All of that is true. But in Tremé, the Creole cottage is also an argument about urban belonging.

As a building type, the Creole cottage is closely associated with early 19th-century New Orleans and is characterized by a roofline running parallel to the street, an orientation that makes the façade feel wide even when the structure is shallow. New Orleans Architecture (the organization and educational platform) describes the Creole cottage as shaped by the city’s humid subtropical climate and as a fusion of French, Spanish, and Caribbean influences.

The “fusion” language is doing real work. It signals that Creole cottage form isn’t just European transplantation; it’s adaptation mediated by the Caribbean, by Louisiana’s climate, and by the labor and knowledge of people who built with local materials and lived with local conditions. In a city where free people of color could, in certain periods, own and develop property, the Creole cottage became one of the built expressions of that fragile freedom.

The HDLC’s Tremé Historic District overview notes “outstanding early Creole cottages dating from the 1830s.” This places the form within the neighborhood’s foundational decades—precisely when Tremé was consolidating as a community of free people of color, artisans, laborers, and later an expanding Black population navigating the tightening racial regime of the antebellum South.

A Creole cottage in Tremé often sits near the sidewalk, sometimes with minimal front setback, suggesting a logic of density and neighborhood intimacy. The porch or gallery, when present, becomes a social threshold—neither fully private nor fully public. That liminal space has long been central to Black urban life: a place to watch and be watched, to greet neighbors, to cool off, to negotiate safety and belonging through presence.

The cottage also carries the imprint of building technique. Brick-between-post (bousillage and related methods in the regional vocabulary) and other hybrid construction approaches appear in historical descriptions of early New Orleans building, reflecting material realities and craft traditions that cannot be separated from the labor systems—free and enslaved—that produced them. Even when the details vary from house to house, the larger point holds: these structures were built by people who understood the environment and the economics of building under pressure.

The shotgun house: A Black Atlantic plan made American

If the Creole cottage is Tremé’s early thesis, the shotgun house is its most widely distributed argument.

The shotgun is a building type so associated with New Orleans that it has become a kind of shorthand for the city. Yet serious architectural research has long insisted that the shotgun is not merely “a New Orleans invention.” The Preservation Resource Center of New Orleans (PRC) notes that scholarly debate about shotgun origins includes hypotheses tied to West African and Caribbean antecedents, with a “Haitian connection” often emphasized in discussions of how the form traveled and transformed.

Tulane’s School of Architecture, in a faculty interview highlighting the “roots” of shotgun houses, similarly points to West African and Caribbean architectural traditions brought by African and Haitian immigrants. That framing is essential for any article that claims to take Black influence seriously. It positions the shotgun not as a quaint local curiosity but as an architectural descendant of the Black Atlantic—migration, displacement, and cultural memory expressed in wood, proportions, and airflow.

The shotgun’s basic plan—rooms aligned front-to-back, typically without a hallway—can be read as efficient and economical, which it is. But it can also be read as social: a plan that organizes life in sequence, with thresholds that are visible and negotiated. Doors aligned from front to back are not simply a trope for tourists; they are a ventilation strategy in humid heat and a spatial discipline shaped by narrow lots and working-class economics.

The HDLC’s Tremé Historic District description observes that the majority of residences are one-story shotguns, with additional larger townhouses and grand homes along Esplanade Avenue. This spatial distribution—shotguns as the common fabric, larger houses as the edge or axis—mirrors a familiar urban pattern: the vernacular supports the neighborhood; prestige architecture frames it.

But Tremé’s shotguns weren’t merely “working-class housing” in a generic sense. They were often built, owned, rented, subdivided, inherited—used as the basic unit of Black neighborhood stability. When Black New Orleanians could access property, the shotgun offered a form that was buildable and expandable. When they could not, it offered a form that could accommodate extended families and informal economies. The plan is modest, but its social capacity is enormous.

This is also where architecture meets policy. In the post-Katrina era, national media accounts of New Orleans have repeatedly used the shotgun house as a symbol of what was at stake—both culturally and materially—when storms and redevelopment pressures threatened historic housing. The Washington Post, for example, describes the shotgun as among the city’s defining vernacular forms and notes its popularity among working classes, including freed slaves and their descendants. That observation is less about nostalgia than about lineage: the shotgun’s prevalence is inseparable from Black life and labor history.

The townhouse: Verticality, capital, and the Creole city

If the shotgun is Tremé’s democratic form, the townhouse is its vertical counterpoint.

Townhouses in Tremé—especially the larger-scale examples noted in HDLC documentation—signal the presence of capital and aspiration. They also speak to the city’s cosmopolitan character: urban forms influenced by European precedents but adapted to New Orleans conditions, including courtyards, galleries, and materials suited to heat and humidity.

The HDLC’s Tremé summary points to larger-scale townhouses from the 1840s and notes that such structures can be found on key corridors like Gov. Nicholls Street. Townhouses are part of how Tremé reads as both neighborhood and city: not merely a residential enclave, but a district connected to commerce, travel, and institutional life.

Crucially, the townhouse also carries Black authorship in New Orleans. Architectural Digest’s reporting on free Black architects highlights how gens de couleur libres families contributed to the development of Creole townhouses and related forms, leaving a legacy visible across historic neighborhoods. And recent scholarship in the Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians—focused explicitly on free people of color and architecture in antebellum New Orleans—examines figures like Norbert Soulié and the professional networks and training that shaped their work.

This matters in Tremé because it prevents the townhouse from being read solely as “elite” architecture imported from elsewhere. In Black New Orleans, townhouses were also sites where Black builders and entrepreneurs could demonstrate expertise, cultivate clients, and translate craft into wealth—within a racial order that constantly threatened both.

Black builders, Black craft, and the invisible workforce

Any account of Tremé’s architecture that focuses only on “styles” misses the point. Styles are the visible layer; labor is the foundational one.

New Orleans’ historic building stock is the product of a workforce that included enslaved people, free people of color, and later Black wage laborers—carpenters, masons, plasterers, ironworkers, painters. Architectural Digest explicitly notes that enslaved people and free craftsmen contributed greatly to the foundation of New Orleans’ architecture and that Black residents had “immeasurable impact” on the city’s built environment.

The challenge for a journalist is to write about that workforce without flattening it into abstraction. The work was skilled, and it was also coerced. Free people of color navigated a narrow corridor of legal possibility; enslaved people labored under violence. Yet the craftsmanship is still present, embedded in joinery, in roof pitch, in the delicate carpentry of brackets and porch trim, in the way buildings sit slightly raised above ground to cope with water.

This is where Tremé becomes a kind of architectural archive of Black survival strategies: build for ventilation because heat is relentless; build raised because water is inevitable; build close because community is safety; build adaptable because economics change and laws tighten.

Architecture and the street: Porches as civic rooms

Tremé’s architecture is designed for the street.

That isn’t a metaphor; it’s literal. Galleries, stoops, porches, and shallow setbacks create a built environment where domestic life leaks into public life. This is not accidental in a neighborhood known for second lines, parading culture, and street-based ceremony. Buildings are the audience and the backdrop—and, in a sense, the co-performers.

The porch becomes a civic room: a place to greet a procession, to play music, to watch children, to negotiate neighborliness. In Black neighborhoods across the South, the porch has historically served as a site of informal governance—where elders watch the block, where news travels, where disputes are mediated before they become emergencies.

Tremé’s building types support this social architecture. The Creole cottage’s relationship to the sidewalk; the shotgun’s front porch as threshold; the townhouse’s balconies and galleries as elevated observation points—each of these is a different way of participating in the street.

If you want to understand how Black influence shaped Tremé’s architecture, you have to understand that it’s not only in the origin theories of a plan type. It’s in how space is used. Tremé’s buildings were made for a community that treated the street as an extension of home.

The rupture: What the expressway did to a neighborhood’s fabric

There is no way to write about Tremé architecture without writing about what threatened it.

In the 1960s, the Claiborne Expressway—an elevated section of Interstate 10—was built through a corridor long associated with Black commerce and community life. The physical impacts—demolition, displacement, visual and noise intrusion—are now widely documented, and the project has become emblematic of how urban highways were routed through Black neighborhoods in the mid-20th century.

Word In Black’s reporting (republishing KFF Health News) describes Tremé residents organizing against the air and noise pollution produced by the Claiborne Expressway, explicitly framing the structure as rooted in racist planning decisions and noting the public health burdens of the highway. This is a crucial lens because it connects architecture to environmental justice: the built environment is not only houses; it is what is built above and around them.

On the local reporting side, WWNO’s account of Claiborne Avenue before and after the interstate recalls the corridor’s earlier identity—its wide neutral ground shaded by live oaks—before bulldozers arrived. Smithsonian Magazine, in a piece about the street’s history and future, frames Claiborne Avenue as once a center of commerce and culture, later cut off and diminished by the interstate.

What does this have to do with Creole cottages and shotguns?

Everything.

Because neighborhood architecture is not merely a collection of structures; it is a system. The value of a shotgun house is not only its cypress framing or its proportion. It is also the block it sits on—its walkability, its commercial corridor, its social institutions, its air quality, its soundscape, its sense of safety. When a highway arrives, it changes the system. Houses may remain standing, but their context—economic, environmental, cultural—can be stripped away.

In Tremé, the expressway didn’t only remove buildings. It altered the neighborhood’s logic, turning a corridor that once stitched the community together into a dividing line. The architecture endured; the ecosystem was damaged.

Preservation, gentrification, and the politics of “historic”

In American cities, “historic” is often treated as an unambiguous compliment. In Tremé, it is complicated.

The very qualities that make Tremé’s architecture desirable—walkable streets, distinctive vernacular forms, proximity to cultural landmarks—also make it vulnerable to speculative redevelopment. The post-Katrina era accelerated these pressures across New Orleans, and Tremé became a focal point in national reporting about gentrification and housing dynamics.

The Washington Post’s long-form reporting on New Orleans ten years after Katrina includes a scene set explicitly in Tremé, describing a side-hall shotgun house and situating it within the emotional and demographic complexity of neighborhood change. The architecture becomes a stage for a larger story: who buys in, who gets priced out, and how cultural neighborhoods can be transformed by capital that arrives claiming admiration.

This is the dilemma of preservation in historically Black neighborhoods: saving buildings is not the same as saving community. A restored shotgun that becomes a short-term rental is still a restored shotgun, but it no longer performs the same social function. A Creole cottage renovated for a new market may remain visually intact while its lineage—its neighbors, its porch life, its intergenerational continuity—is severed.

Tremé’s built environment therefore forces a more demanding preservation question: preservation for whom?

Reading the details: Where Black influence lives in plain sight

The most persuasive evidence of Black influence on Tremé architecture is not always found in dramatic stylistic markers. It is found in the persistence of certain choices—choices that reflect cultural memory, climatic knowledge, and community needs.

1) Ventilation as design ethic

Shotguns and cottages alike are structured to move air. That is climate adaptation, yes, but also cultural knowledge from places where heat is not a season but a constant.

2) Threshold spaces as social infrastructure

Porches, galleries, stoops—spaces that allow surveillance and sociability. In a neighborhood built under racial constraint, visibility can be both protection and vulnerability, and architecture mediates that tension.

3) Adaptability as wealth strategy

Double shotguns, camelbacks, rear additions—these are not only stylistic variations. They are responses to changing family structure and economics. The HDLC notes the prevalence of double shotguns in late 19th-century Tremé. That form is architecture as income model: two units, shared wall, more rent potential, more flexibility.

4) Craft as identity

Ornamental millwork and porch trim are often dismissed as decoration. In Tremé, decoration is a public declaration: of pride, of skill, of belonging. Craft is one of the ways Black builders left signatures in a world that often refused to credit them.

5) Urban form as cultural form

Tremé’s architecture is inseparable from its street culture. The buildings are arranged in a way that supports gathering—parades, funerals, second lines—where the street is not a corridor but a communal room.

The free people of color as developers, not just residents

One of the most significant corrections contemporary scholarship and journalism have made is to reposition free people of color not only as occupants of historic neighborhoods, but as developers and shapers of the city itself.

PRC’s discussion of new research on free people of color emphasizes how builders like Norbert Soulié operated in real estate and construction networks, shaping Creole townhouses and related urban forms. The Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians article similarly examines how free people of color navigated training, patronage, and professional relationships within antebellum architectural history.

In Tremé, this shifts the narrative from “Black influence” as a vague cultural aura to Black influence as concrete authorship: decisions about materials, plans, façades, siting, and neighborhood development.

It also reframes Tremé’s architecture as a repository of Black economic history. Buildings are assets; neighborhoods are portfolios. The fact that free people of color built and owned property in Tremé is not incidental—it is foundational to why Tremé became, and remained, a Black neighborhood with institutional depth.

What counts as influence?

Influence can be a soft word. It can imply that Black Americans merely “inspired” a style while others executed it. Tremé’s architecture requires a harder definition.

Black influence in Tremé includes:

Authorship: free Black architects and builders designing and constructing key forms, including Creole cottages and townhouses.

Transmission: African and Caribbean building traditions shaping the shotgun house’s lineage and persistence.

Occupation and use: Black families turning vernacular types into social systems—porch life, mutual aid, block culture—that made the architecture function.

Stewardship: community-based preservation, advocacy against harmful infrastructure, and efforts to maintain neighborhood life under market pressure.

This is architecture not as static artifact, but as ongoing practice.

The present tense: Why Tremé’s buildings are still contested

Today, Tremé’s architecture sits at the intersection of multiple pressures:

Environmental vulnerability in a city shaped by water, heat, and storm risk

Infrastructure debates about what to do with the Claiborne Expressway and how to repair historic harms without triggering displacement

Tourism economies that convert neighborhood character into commodity

Housing affordability challenges that threaten the continuity of culture-bearers

In this context, a Creole cottage is not only a picturesque building type. It is a question: will the people whose histories are embedded in these forms be able to live behind those façades in ten years?

A shotgun house is not only a plan. It is a claim about what matters in a city: the right of working-class and Black residents to occupy historic neighborhoods near the center, rather than being pushed outward as the core becomes an amenity zone.

A townhouse is not only verticality. It is a reminder that Black New Orleans has long contained sophistication, capital strategy, and professional expertise—despite narratives that treat Black neighborhoods as culturally rich but economically marginal.

A closing walk: The architecture as moral inventory

Imagine ending a walk through Tremé not at a landmark, but at a typical block—because the typical is the point. The cottages, shotguns, and townhouses together form a streetscape that reads as a collective decision, repeated over time: to build close, to build resilient, to build with an eye toward neighbors and weather and music, to make domestic space legible as public belonging.

Tremé’s architecture tells a Black American story in a register many cities prefer to avoid: not only suffering, not only artistry, but expertise—spatial intelligence, development strategy, construction craft, and a hard-earned understanding of how to make community durable under pressure.

The houses remain. They have been repaired, painted, raised, trimmed, sometimes gutted, sometimes saved at the last moment. They are still doing their work: holding memory, hosting life, framing the street.

What Tremé asks—quietly, through rooflines and porches and narrow plans—is whether the city will finally treat that work as valuable enough to protect not just the buildings, but the people who made them matter.

And if the answer is yes, it won’t be because someone admired a façade. It will be because New Orleans, and the country watching it, decided that preservation means more than keeping the shape of a neighborhood. It means keeping its authors.

You’re absolutely right, Charlie Smalls was a force