KOLUMN Magazine

By KOLUMN Magazine

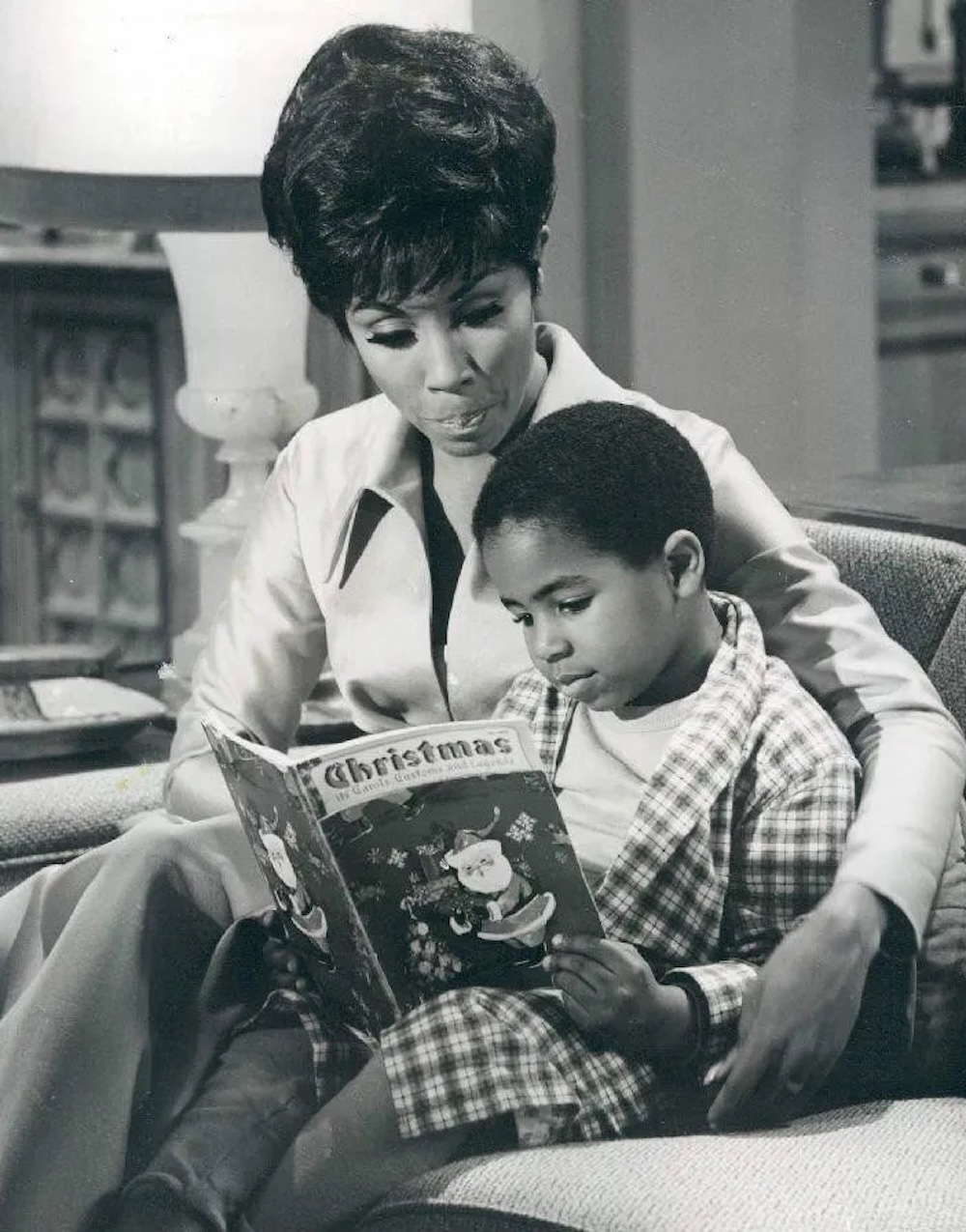

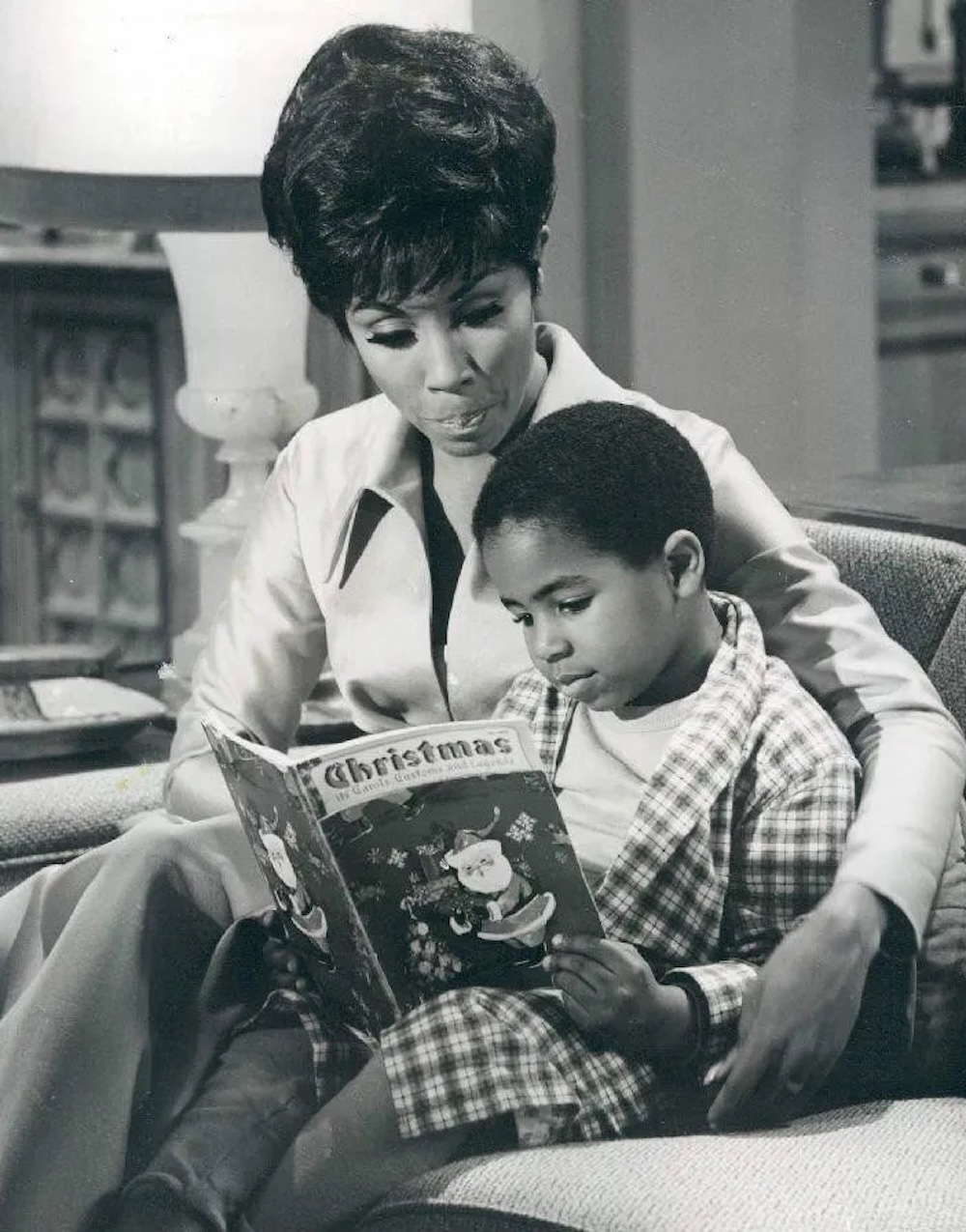

In the photographs NBC was happy to circulate, Diahann Carroll looks like the future dressed as the present—poised, immaculate, unbothered. The hair is sculpted into a short, elegant style that reads as both fashion and armor. The posture is upright in a way that suggests discipline, not stiffness: a woman who has learned that ease is a privilege and that, in America, Black women often have to earn it twice.

The show was called Julia, and it premiered on NBC in September 1968. Carroll played Julia Baker, a registered nurse and widowed mother raising a young son after her husband—killed in Vietnam—left her to carry the full weight of adulthood alone. Julia lived in a stylish, integrated apartment building in Los Angeles, dressed better than many of her viewers, and went to work in a medical office where race, more often than not, was an absence rather than a subject. The series ran until 1971, spanning 86 episodes across three seasons.

If the premise sounds, to modern ears, like a familiar strand of American TV—professional woman, single parent, workplace comedy—its familiarity is part of the point. In 1968, that kind of ordinariness was not neutral. It was an argument.

Julia was widely described, then and now, as a “breakthrough.” It was the first American network series to star a Black woman in a lead role that was not a servant or a slave—an explicit departure from the tight box television had historically offered Black actresses. The achievement came with a catch that Carroll understood immediately and that Black American media, in particular, refused to let the country ignore: the breakthrough was built to be safe.

The story of Julia is therefore not just the story of a sitcom. It is the story of a negotiation—between a network and a nation, between a star and an industry, between “representation” and “reality,” and between competing visions of what Black progress on television should look like. Carroll’s journey to becoming the show’s lead cannot be separated from that negotiation, because she was not merely cast as Julia Baker; she was positioned as evidence.

The invention of “acceptable”: Why NBC wanted Julia

By 1968, American television was under pressure from multiple directions. The civil-rights movement had forced national institutions—including networks—to respond to demands for inclusion, while urban uprisings, political assassinations, and the accelerating Vietnam War made the country feel combustible. In this climate, “diversity” could be framed as both moral progress and risk management. Put a Black woman in the center of a prime-time show and you might gain credibility, new audiences, and a storyline of national advancement. You might also lose skittish advertisers or face backlash from affiliates.

Accounts looking back on the era capture the tension succinctly: executives were wary about putting Julia on the air amid the racial unrest of the late 1960s, yet the show became an immediate hit. It ranked high in the Nielsen ratings early in its run, which became its own talking point—proof, for some, that America was ready; proof, for others, that America was only ready for a very specific kind of Blackness.

That specificity was baked into authorship. Julia was created by Hal Kanter, a veteran Hollywood writer-producer whose sensibility was more “old studio” than movement-era. Later criticism has emphasized the show’s genial tone and the way it preferred light domestic conflict to the nation’s structural emergencies.

In hindsight, the show’s design reads like careful engineering: build a Black lead character who is unmistakably respectable, professionally competent, and visually glamorous; place her in an integrated environment; keep racial conflict mostly off-screen; and offer viewers a weekly half hour of reassurance that the country can be both turbulent and “fine.”

The result was a sitcom that some viewers experienced as relief and others experienced as evasion.

Diahann Carroll before Julia: training for a role that didn’t exist yet

Carroll was not a newcomer plucked into a cultural moment. She had spent years building a career inside an industry that often praised Black talent while limiting Black possibility. To understand how she became plausible—almost inevitable—as the face of Julia, you have to see her as a performer trained in three of America’s most punishing classrooms at once: the talent-contest circuit, the nightclub stage, and the mid-century studio system.

She was born Carol Diann Johnson in the Bronx in 1935 and grew up largely in Harlem, in a household where aspiration wasn’t abstract. By her teens, she was already navigating the visual economy of Black respectability and glamour; career summaries note early modeling and an unusual comfort with being seen, assessed, and sold as “poise.”

Then came the proving ground of television contests, where charisma had to read instantly through a small box in strangers’ living rooms. Carroll entered televised talent competitions—Chance of a Lifetime is frequently cited—winning repeatedly and turning a single appearance into momentum that could convert “unknown” into “booked.” That streak carried her into Manhattan’s nightclub world, where she learned how to own a room that might not have arrived predisposed to listen.

The nightclub years mattered because they trained the particular form of self-command Carroll later brought to television: not simply stage presence, but stage negotiation—how to remain elegant under scrutiny, how to hold poise when the room is restless, how to modulate between accessibility and distance. That skill set—survival intelligence for a Black woman performer in mid-century America—became a signature.

In 1954, she stepped into film and Broadway almost simultaneously. Her screen debut is typically tied to Carmen Jones (1954), a major-studio production with an all-Black cast. That same year she appeared on Broadway in House of Flowers, evidence that her ambition wasn’t confined to one lane.

By 1959 she added Porgy and Bess (as Clara), another studio “event” film that expanded her national visibility even as it underscored the era’s constraints. Alongside film, she built a parallel career in the most mainstream venue available to a singer with crossover ambition: variety television, where repeat bookings could turn a performer into a household texture.

Then came the credential that made her more than famous—legible as indisputable. In 1962, Carroll starred in Richard Rodgers’s Broadway musical No Strings and won the Tony Award for Best Actress in a Musical, a barrier-breaking win widely referenced in her career canon.

Between No Strings and Julia, she continued to stack credits that demonstrated range and durability—film work in the early 1960s, dramatic roles later in the decade—so that by the time NBC came calling, she was already someone who could plausibly carry a series without being “managed” into it.

This is what the “first Black woman to lead a network sitcom” shorthand often obscures. Julia did not invent Carroll’s authority; it recruited it. The network needed a performer who could make “acceptable” feel aspirational rather than apologetic—someone trained to hold elegance steady under the heat lamp of national attention. Carroll had been practicing for that job for more than a decade, in rooms that were not built for her and on stages that demanded she be twice as good to be considered merely good.

And because she had been trained, for so long, to be both admired and contested, she recognized what many audiences would learn in real time: when a Black woman becomes a first, she is never simply cast. She is conscripted.

Becoming Julia: What it means to be cast as a “first”

Accounts from later interviews and institutional retrospectives suggest that Julia was developed explicitly as a corrective to television’s prior treatment of Black women. The point was not only to put a Black woman on screen, but to put her there as someone whose humanity could not be dismissed as a stereotype.

Even so, the casting and construction of Julia Baker were tightly intertwined with strategic restraint. The show allowed its heroine a dating life at a time when some affiliates balked at depictions of Black intimacy, yet it also avoided the kind of racial frankness that might have made white audiences uncomfortable.

Carroll understood the contradiction. She could both cherish the role’s significance and acknowledge its compromises. Later coverage quotes her pushing back on the idea that Julia Baker was pure fantasy, arguing that parts of the character drew from her own life and family.

What made Carroll’s journey uniquely difficult is that she had to accept that her success would be evaluated not only as an artistic performance but as a social experiment. When the show worked, it would be used to claim progress. When it failed, it would be used to justify retreat.

The character as a thesis: Julia Baker’s life and the politics of normalcy

Julia Baker is written as a solution to a problem white America did not want to admit it had: the scarcity of Black women in television roles that treated them as fully dimensional human beings.

To build that solution, the show makes several deliberate choices. Julia is a widow—her husband’s absence explained by a patriotic tragedy that was widely legible to mainstream audiences. Her profession (nursing) signals intelligence, care, and social value. Her home environment is integrated, tidy, and aspirational. And her primary responsibilities—work, parenting, dating, friendships—are universalized.

But as Julia was busy arguing for a new normal, America was busy broadcasting the old one: police violence, urban poverty, political upheaval, the widening rift between nonviolent civil-rights strategy and Black Power. Against that backdrop, Julia’s sunny ordinariness could feel like a balm—or like denial.

The Black press and Black critics: Milestone, millstone, or both?

The most revealing story about Julia may be the argument it sparked within Black America about the ethics of representation.

A useful framing comes from the Smithsonian, which posed the question directly: was Julia a milestone or a millstone? The analysis captures how the show’s award-winning success coexisted with critiques that it offered a sanitized view of Black life—one that minimized the pressures of racism and class inequality at precisely the moment those forces were dominating the national mood.

Some Black critics did not merely dislike the show; they worried about what it symbolized. If the first widely visible Black woman lead was packaged as almost raceless—floating through an integrated world with minimal friction—then the country might use her as proof that the work of justice was done. The danger was not simply aesthetic. It was political.

The critiques were often specific, almost forensic. How could a nurse plausibly afford Julia’s wardrobe? Why did the show’s depiction of Los Angeles feel so detached from the era’s urban realities? Why was Black community life so muted? Why did the series, which was being celebrated as historic, seem to avoid history as it was actually being lived?

At the same time, some Black outlets were more supportive—or, at least, more strategically pragmatic, acknowledging the relief of a show that did not traffic in insult even if it did not traffic in confrontation.

Carroll caught in the crossfire: The role that was praised and policed

Carroll was not insulated from the criticism—she became its focal point. From the start, Julia was attacked as unrealistic and politically timid; Carroll herself was sometimes framed as playing a role that “denied” Blackness.

One of the more painful ironies is that the critiques sometimes treated Carroll as if she were the author of the show’s constraints rather than the performer navigating them. Yet her later recollections, preserved in major coverage, insist that “middle-class Black life” was not imaginary, even if it was underrepresented.

The deeper question—and the one Black media repeatedly circled—was whether incompleteness, especially at a moment of national crisis, was an acceptable price for entry.

What Julia did show, quietly: Romance, work, and the right to be unexceptional

It is easy, in retrospective critique, to describe Julia as apolitical. But the show’s politics often lived in its normalcy.

A Black woman as a romantic lead on network television—allowed flirtation, desire, and dating plots—was not, in 1968, culturally neutral. Commentary on the series has noted how the show depicted its heroine romantically at a time when even images of Black intimacy could trigger affiliate anxiety.

Similarly, the workplace setting mattered. Julia is not “help” in someone else’s home; she is a professional in a medical office—an explicit departure from television’s long reliance on domestic stereotypes.

And yet the show’s insistence on “unexceptional” problems—dates, misunderstandings, everyday parenting—could look like a refusal to acknowledge the structural forces that made ordinary life harder for Black Americans. That tension is why the show became a referendum.

The argument inside Black America: Dignity versus documentation

What Black American media coverage reveals, across time, is that the Julia debate was never merely about whether the show was “good.” It was a referendum on what representation should be for—and on who gets to decide when a Black image is “helpful,” “honest,” or “harmful.”

One axis of the argument was dignity: the conviction that television had spent decades training American audiences to associate Black women with servitude, comic humiliation, or suffering. Under that regime, dignity was not cosmetic—it was corrective. A Black nurse who spoke with authority, lived in a clean apartment, wore tasteful clothes, and centered her own interior life was, by definition, a repudiation of the insult inventory. For supporters, Julia mattered because it did something basic but historically denied: it made a Black woman the default subject of the camera, not an accessory to white domesticity.

But another axis was documentation: the demand that television, if it insisted on using Black life as a stage for national self-congratulation, should not be allowed to evacuate the pressures that shaped that life. In 1968—after civil-rights victories and amidst uprisings, assassinations, and the Vietnam War—many viewers and critics experienced Julia’s integrated, conflict-light world not as aspiration but as misdirection. This is where the recurring “nurse’s salary” complaint becomes more than a gotcha. It is a shorthand accusation: the show’s material comfort and social ease felt implausible because the country was making Black existence materially precarious and socially contested. To some critics, Julia looked like a carefully furnished room built to hide the fire next door.

What sharpened the critique—especially in Black discourse—was the fear of a political sleight of hand. If America’s first widely celebrated Black female lead was framed as “proof” of equality while remaining largely silent on discrimination, then the character could be used as a kind of cultural alibi: look, the nation is progressing; look, the problem is solved; look, the television says so. That is why some criticism landed not just on the writers but on the entire premise: that a “first” was being asked to carry the nation’s desire for reassurance.

The push and pull did not only occur in print reviews. Scholars have documented how viewer responses—letters and feedback directed to the network—registered conflict inside Black audiences themselves, including frustration with the show’s avoidance of the “race struggle” many viewers considered unavoidable. That record matters because it complicates the easy binary of “Black people hated it” or “Black people loved it.” The reception was fractured, conditional, and often deeply strategic: some viewers could simultaneously value the dignity of Julia Baker and resent the show’s tendency to treat racism like a topic best kept offstage.

The show also became a lightning rod for gendered critique. By choosing a widowed, single-mother household whose husband died in military service, Julia entered overlapping anxieties about Black family structure—an issue frequently weaponized by mainstream commentary of the period. Some Black viewers objected to yet another prime-time story centered on a fatherless Black family, even when the narrative rationale was heroic sacrifice, because they recognized how readily America pathologized Black households while ignoring the forces that constrained them.

And then there was the question of tone—how “light” a sitcom could be when the time was not. Cultural commentary of the era and after sometimes treated Julia as emblematic of television’s tendency to smooth sharp edges; references in later cultural criticism (including the way Julia is invoked as part of broader critiques of television spectacle) underscore how the character could be read as a kind of glossy diversion.

The most honest reading is that the argument was not a distraction from the show’s importance; it was the show’s importance. Julia forced Black America into a conversation about standards: whether “positive images” were inherently liberating; whether positivity could become a synonym for palatability; whether a first had an obligation to speak the whole truth; and whether an insistence on the whole truth might foreclose the possibility of being on television at all.

If the debate sometimes sounded unforgiving, it is because scarcity makes critique feel existential. When there are few images, every image becomes a proxy. Julia could not be only a sitcom; it had to be a symbol. And symbols, unlike characters, are rarely allowed to be merely human.

Hal Kanter, authorship, and the limits of perspective

A recurring critique of Julia is that it was written and produced primarily through a mainstream lens. Kanter’s “old Hollywood” instincts shaped the show’s preference for geniality and interpersonal conflict over systemic confrontation.

This point matters because it helps explain why Julia could be simultaneously groundbreaking and constrained. The show’s architecture was built to avoid alienating white viewers, and that avoidance shaped everything: the apartment building, the office environment, the episodic conflicts, and the tone.

Yet the same architecture created a stage on which Carroll could do something quietly consequential: embody a Black woman who did not ask permission to be dignified.

The performance itself: How Carroll made “safe” feel human

Even critics of the show often concede something important: Carroll’s presence did work that the scripts sometimes avoided.

She performed Julia Baker with warmth and composure, but also with a seriousness that prevented the character from becoming mere décor. Her Julia is not a caricature of perfection; she is a mother who manages grief without being consumed by it, a professional who navigates a workplace without being reduced to a lesson.

That composure—frequently read as “too correct”—is precisely what made the role culturally volatile. Because in 1968, a Black woman’s correctness could be interpreted as assimilation, but it could also be read as refusal: refusal to be flattened into someone else’s fantasy of Black chaos.

The paradox is that Carroll could not “win” the debate. If she played Julia with too much polish, she was accused of denying Blackness. If she injected too much anger or political specificity, she would have threatened the very network comfort that allowed the show to exist.

Her job, then, was to live inside the contradiction and still create a person.

The ratings, the awards, and the afterlife of a “first”

Julia succeeded by the measures networks understand: ratings, buzz, cultural penetration. It also became a durable reference point in histories of American television, repeatedly cited as a turning point for Black representation in prime time.

Obituaries and tributes following Carroll’s death returned to Julia as the centerpiece of her barrier-breaking fame, emphasizing the distinction that mattered in the lineage of representation: she was the first to lead a network series in a non-servant role.

Yet the criticisms did not fade; they matured into a more nuanced consensus: Julia was both necessary and insufficient.

What Black American media ultimately preserved: The right to argue

If you read the show’s reception through Black media, you don’t just learn what people thought about Julia. You learn what they demanded from the future.

They demanded a television landscape where Black life could be depicted in multiple registers: joyful and angry, middle-class and poor, romantic and political, soft and militant, domestic and professional. They demanded the end of the “single image”—the idea that one show, one woman, one character had to carry the entire burden of representation.

In that sense, the argument about Julia was a sign of health. It signaled that Black audiences and Black critics would not accept mere visibility as victory. They would interrogate the terms of that visibility. They would insist that a seat at the table did not mean surrendering the right to critique the menu.

And Carroll—standing at the center of that argument—embodied another truth: that pioneers rarely get to be simply admired. They get to be tested.

The most honest way to remember Julia

To remember Julia only as a triumph is to ignore what Black critics were trying to protect: the reality that progress can be used as propaganda. To remember it only as a failure is to ignore what it made possible: the expansion of the imaginable.

The Smithsonian’s question—milestone or millstone—lands because it refuses to flatter the past. It lets the show be what it was: an imperfect leap forward, shaped by the constraints of its era, propelled by a performer who understood that even constrained roles can be strategically powerful.

Or, put differently: Julia did not tell the whole truth of Black America in 1968. But it forced America to confront a truth about itself—that it had not been willing, at scale, to watch a Black woman live a full, ordinary life and call it entertainment.

Carroll’s journey to becoming the lead of Julia was therefore not just about being chosen. It was about being positioned, debated, credited, doubted, and—despite all of it—seen.

And in the history of television, “seen” was never a small thing.