By KOLUMN Magazine

On certain afternoons in Harlem—ones with a bright, hard light that makes every brick look newly scrubbed—you can imagine how the work began: not as an institution, not as a “program,” but as a knock at a door.

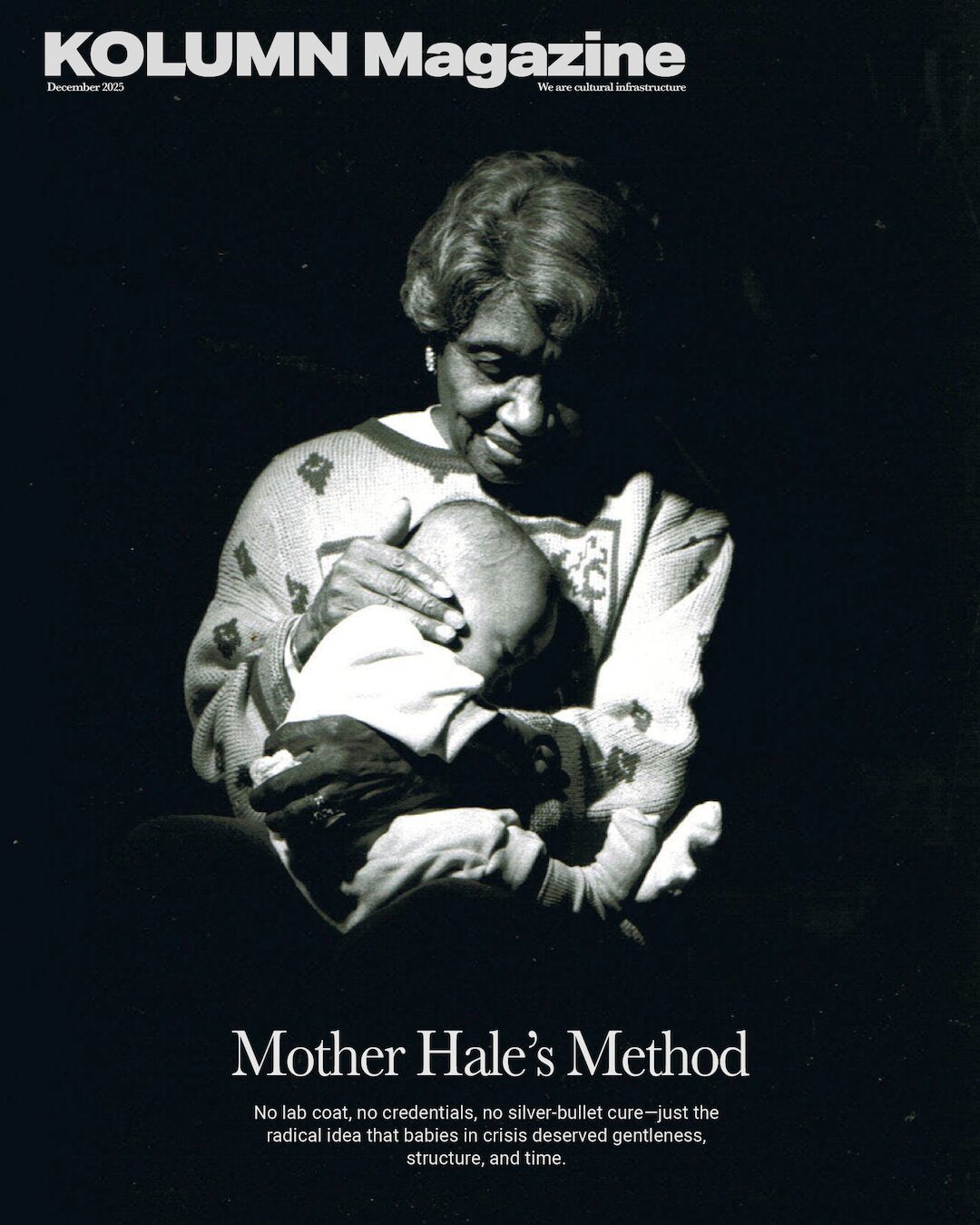

In 1969, Clara McBride Hale was in her mid-60s, at the age when most people are bargaining for rest. She had already lived multiple lives inside one life: an orphaned teenager who finished high school anyway; a young wife who became a widow; a working mother who took in other people’s children to keep her own afloat. By the time that Harlem’s drug crisis took on the grim glamour of national attention, she had long practiced a quieter form of survival—keeping children fed, clean, held, and safe on the kind of budget that forces you to become inventive about everything, including hope. The biographies tend to flatten this into a saint’s timeline. The more accurate version is messier: a woman who learned, through attrition, that the world will keep producing emergencies whether you are ready or not—and that you can either close your door or become the kind of person whose door stays open.

The story told in news reports has the clean inevitability of myth, but it begins with something close to accident. Lorraine Hale, Clara’s daughter, saw a woman in Harlem who appeared to be in a drug trance, a baby in her lap, the baby’s safety hanging by a thread. “In a great act of impetuousness,” Lorraine later recalled, she got out of her car, lectured the woman, and told her to take the baby to her mother.

The next day, Clara called Lorraine with a sentence that sounds almost comic until you feel the weight of it: “There’s a junkie at my door and she says you sent her.”

Clara did not want a “junkie baby,” she said. She didn’t know anything about them. She tried to send the woman away. And then—depending on which retelling you read—the mother left the infant anyway, or returned with more children, or word spread fast enough that soon Clara had a small ward of newborns whose bodies were teaching them, minute by minute, what withdrawal looks like.

The city tried to shut her down. She asked for help. With a federal grant, a vacant city-owned five-story brownstone was renovated into what became Hale House.

It’s worth pausing on the pivot here, because it contains the essence of Clara Hale’s success: she did not merely provide charity; she converted private compassion into public infrastructure. Where government saw a compliance problem—a home operating outside licensing rules—she saw an unmet obligation. And because she did not speak in the bureaucratic dialect of systems, she spoke instead in the grammar of family: babies belonged somewhere safe, and if the system didn’t have that place ready, she would build it with her own hands and then dare the system to catch up.

“Love them.” The philosophy that sounded too simple—until it wasn’t.

Many of the most enduring quotes in the Hale House story come from Clara herself, because she was unusually consistent about refusing the era’s appetite for technical jargon and miracle cures. Her “method,” in public, was disarmingly direct. “It wasn’t their fault they were born addicted. Love them. Help one another, love one another,” she said, explaining the philosophy behind the program.

There are two ways to read that line. The first is as sentiment—something you might say at a podium and then promptly forget when the cameras leave. The second is as a discipline: a daily choice to treat infants not as symptoms, not as social contamination, not as cautionary tales, but as people worthy of routine tenderness. Hale House, as described in contemporary reporting, tried to operationalize that discipline.

By 1990, Hale House was described as a five-story Harlem brownstone where Clara Hale and a small staff cared for hundreds of babies born addicted to drugs and some infected with HIV in utero. That detail—HIV-infected infants—can blur in the mind now, but in the late 1980s and early 1990s it carried additional stigma and fear. Hale’s response was characteristically plain: she treated those babies “much the same” as the others, and in at least one case kept a young child infected in utero as her roommate, emphasizing she had not contracted AIDS.

To modern ears, this sounds like a public service announcement. In context, it was a rebuke to panic. Hale was insisting, with the authority of practice, that care could be both intimate and safe—and that the dehumanization of sick children was not inevitable.

Her public image grew accordingly. President Ronald Reagan cited her in a 1985 State of the Union address as “an American hero.” Later reporting described her seated near the First Lady in the visitors’ gallery when that salute arrived, and Hale—who was ill at the time—went anyway. “When the President called, I was sick, but I went anyway,” she said later. “I wanted the kids to see it and know it.”

If you want to understand how Hale navigated politics without becoming political, start there. For her, the spectacle wasn’t the point. The children were. Recognition mattered not as ego, but as proof—evidence she could hand to the kids—that the world had noticed them, that their beginnings did not disqualify them from attention.

The testimonies that make the place real

Institutions are often defined by their budgets, their square footage, their annual reports. Hale House—at least in the coverage that cemented its myth—was defined by scenes.

One of the clearest is not in Harlem at all, but in Los Angeles, where Hale traveled in 1990 at the urging of a local organizer who had visited Hale House and, as Hale put it, had been “kind of adopted” by her. The writer Beverly Beyette describes “Mother Hale” eating chitterlings in Compton, dousing them with red pepper sauce, and joking—half-joking—that her daughter only allowed this once a year.

That scene matters because it reintroduces Hale as a person rather than a halo. She could be mischievous. She could tease. She could enjoy food. And then, after lunch, she could go sit in a circle with twenty women—many of them staff—rocking in a chair, and narrate the origin story again: the day a young woman appeared at her door with a drug baby, and Hale said, “You must have the wrong house.”

From that same report comes a smaller testimony, offered almost in passing but heavy with meaning: more than one young woman told Hale, upon meeting her, “You remind me of my grandmother.” The line reads like a compliment. It also reads like an unmet need. In the era’s public imagination, addicted mothers were frequently framed as moral failures rather than as people caught in interlocking crises—poverty, trauma, racism, inadequate healthcare, predatory markets, punitive policy. Hale’s presence offered something the system rarely did: an older Black woman’s steady gaze that did not begin with disgust.

Another testimony comes through Lorraine Hale, whose “impetuousness” effectively expanded her mother’s household overnight. It would be easy to narrate Lorraine as a mere catalyst. But in the Associated Press account republished by the Los Angeles Times and The Washington Post, Lorraine appears as a witness to how quickly a private home can become a community resource. She describes seeing the endangered baby in the mother’s lap and choosing intervention over distance. In doing so, she also documents the logic of the block: you notice, you act, you bring the problem to someone you trust, because the alternative is to let the street absorb another child.

Then there are the workers—people whose labor is often erased in the founder narrative, but whose testimonies reveal what the daily reality demanded.

In a 1992 Associated Press story about crack-exposed children, Hale House nurse Anne Marie Nedd describes the way pity can become its own kind of prejudice. “When people find out what I do, they say, ‘Oh, those poor crack babies,’” she said, chasing an energetic toddler around Morningside Park. “I get so mad. I tell them, ‘There’s nothing really wrong with these kids!’”

This is testimony in its purest sense: a person who has seen the children up close rejecting the story the country is telling about them. It also points to one of Hale House’s most important contributions—its quiet insistence on normalcy. The children in that story are doing ordinary kid things: running toward swings, climbing jungle gyms, mastering slides. The ordinariness is the miracle, precisely because the era was busy branding them as monsters.

The AP report explicitly frames the contradiction: “crack babies” had become a national buzzword, a “soundbite” conjuring “mutant, monster children.” Hale House—through daily care and through the testimony of people like Nurse Nedd—offered a corrective. Not denial. Correction: many children exposed to crack in utero might develop more slowly, but could rise above dire predictions; in other words, fate was not fixed at birth.

This aligns with later retrospectives on the “crack baby” moral panic, which document how media narratives frequently exaggerated or distorted long-term outcomes, often ignoring the roles of environment, poverty, and policy.

Hale House did not write academic rebuttals. It did something more persuasive: it took the children to the park.

Harlem in the late 20th century: The context that made Hale House necessary

To describe Hale House as a “home for drug-addicted infants” is accurate and insufficient. Hale House existed because Harlem—and Black urban America more broadly—was forced to absorb overlapping policy failures: inadequate housing, underfunded schools, scarce treatment infrastructure, aggressive policing, and the kind of economic abandonment that turns every personal crisis into a community emergency.

In the AP accounts of Hale’s life, there is a pattern: institutions appear not as stable supports but as forces that arrive late, often with rules. City officials tried to close her initial operation. But those same systems eventually facilitated the expansion through a federal grant and a renovated brownstone.

That sequence—punishment, then belated partnership—is a familiar American rhythm, especially in Black neighborhoods. It is also central to understanding why Clara Hale became “Mother Hale” rather than merely “Clara.” She provided continuity in a landscape where official help was episodic and conditional.

Hale herself framed her work as part of a Black communal tradition: “Years ago, when we first got out of slavery, we would take our sisters’ children,” she told a group of women in Compton, recalling that children “never went into institutions.” You can read this as nostalgia. You can also read it as social theory: a description of kinship networks that functioned as informal community care systems when formal ones were hostile or absent.

The crack era tested those networks. When addiction spreads faster than treatment capacity, when incarceration becomes a default response, when social services are both stigmatized and under-resourced, families fracture under the weight. Hale House entered that fracture zone with a proposition: if the mothers couldn’t hold the babies safely, someone else would hold them—without surrendering them to a cold system.

This is one of the most difficult moral terrains in social policy: caring for children while not simply criminalizing or shaming parents. Hale House’s own stated principle, as reported by the Associated Press, was to return children to families after recovery and parental treatment when possible. That detail matters because it complicates the simplistic rescuer narrative. Hale was not building an orphan factory. She was trying—within the limits of an overstressed system—to act as a bridge.

What made Clara Hale effective: A practical inventory

Clara Hale’s success is often rendered as personality. But if you read the coverage closely, her effectiveness was structural as well—an accumulation of tactics.

1) She built trust with minimal friction.

Word spread quickly, Hale said, that “there’s a crazy lady up in Harlem… and she won’t charge you nothing” to care for babies. In communities where “help” often comes with surveillance, fees, or judgment, the absence of friction is itself a service.

2) She treated infant care as both emotional labor and technical labor.

She had “no formal training,” an AP story notes; her approach was “hands-on caring and love.” It’s tempting to romanticize that. But “hands-on” in this context includes staying close enough to respond to withdrawal cries, rocking babies in the night, tracking feeding, managing the physical symptoms of detox. The reporting describes newborns placed in cribs in Hale’s bedroom so she could rock them when they cried “in the agony of withdrawal.” That is not metaphor. That is a work shift.

3) She insisted on a counter-narrative when the dominant one was fatalism.

The crack baby panic—“mutant, monster children”—was not simply insulting; it shaped policy priorities and public willingness to fund humane interventions. Hale House’s visible toddlers and frank staff testimony—“There’s nothing really wrong with these kids!”—was a corrective in real time.

4) She leveraged symbolism without becoming captive to it.

Reagan’s “American hero” line put Hale House on a national stage. Hale used that attention, at least as she described it, to elevate the children’s sense of possibility. In the ecology of nonprofit survival—especially Black-led work—visibility can translate into donations, partnerships, and protective scrutiny.

5) She built something that felt like family, even when it was large-scale.

Hale House was repeatedly described as “not an institution” but a home, with siblings, hugs, bedtime stories—an environment designed to soften the clinical hardness of the children’s beginnings. Whether every child experienced it that way is impossible to prove from the outside. But the aspiration itself—home rather than warehouse—was central to its identity.

The measure of success: Numbers, yes, but also scenes

Success in social care is notoriously hard to define. Is it survival? Is it reunification? Is it educational attainment decades later? Hale House coverage tends to oscillate between numbers and scenes.

The Associated Press obituary account says more than 800 babies benefited from Hale’s work. Other reporting in 1987 and 1990-era retrospectives uses “over 500” and similar tallies depending on the time frame being described. (These shifting numbers are not necessarily contradictions; they reflect growth across different reporting years.)

But the more powerful measure may be what the 1992 AP story depicts in the park: children “indistinguishable” from others, moving through the city with the uncomplicated entitlement of childhood—slides, swings, cheering.

That kind of normalcy is not a small thing for children who began life as public fears. It is, arguably, a political outcome.

The uncomfortable coda: Legacy after the founder

Any responsible account of Hale House must acknowledge that the institution’s post–Mother Hale era became entangled in controversy—precisely because the organization had accumulated money, fame, and public trust.

After Clara Hale’s death in December 1992, leadership passed to her daughter, Lorraine Hale. In 2001, major outlets reported investigations into alleged financial irregularities and governance problems, including Lorraine Hale’s resignation amid scrutiny. The existence of later mismanagement does not negate what Clara Hale built; but it does remind us of a persistent vulnerability in founder-driven nonprofits: once a charismatic moral authority is gone, the institution can become exposed—especially if governance structures were built around reverence rather than controls.

This is also where the country’s relationship to Black-led care work becomes complicated. When a Black woman builds an institution through grit and trust, the public is eager to mythologize. When the institution later stumbles, the public can be eager to dismiss the entire enterprise as naïve or corrupt. The more honest stance is to separate the founder’s model—its ethics, its daily practice—from the later administrative failures, while still naming them.

If Hale House demonstrates anything beyond Clara Hale’s personal courage, it is that love—when scaled—requires scaffolding: accountable boards, transparent finances, durable partnerships. Clara Hale built the house. The question of how America maintains such houses after the builders are gone remains unsolved.

Why Clara Hale still matters

Clara Hale is not merely a heartwarming figure in the archive. She is a case study in what becomes possible when care is treated as a civic technology.

She operated in the gap between what the state would do and what the neighborhood needed done. She built legitimacy from the ground up, through the oldest credential there is: showing up again tomorrow.

Her language remains bracingly relevant because it refuses the moral contortions that often surround addiction. “It wasn’t their fault,” she said, returning the blame to where it belongs: not on infants, not on suffering mothers alone, but on the conditions that make suffering predictable.

And her staff’s testimony—angry at pity, protective of children’s dignity—still reads as a critique of how America narrates vulnerable people. “There’s nothing really wrong with these kids,” Nurse Nedd insisted, not claiming they had no needs, but refusing a story that turned needs into doom.

Hale House was not magic. It was labor: rocking chairs, night watches, paperwork battles, funders, public scrutiny, the ongoing work of turning one woman’s impulse to hold a baby into an institution that could hold hundreds.

In an era when society often treats care as an afterthought and punishment as policy, Clara Hale’s record suggests a different hierarchy: start with the child, refuse shame as a strategy, and build the system around the act of keeping someone alive—then loved—then possible.

That is the success story. Not perfection. Not myth. A practice that, for thousands of nights in Harlem, sounded like a crying baby getting picked up.