By KOLUMN Magazine

On paper, it reads like a headline built for a broadly engaging social media package: a young Black cowgirl makes history on national television. The first. The youngest. The future.

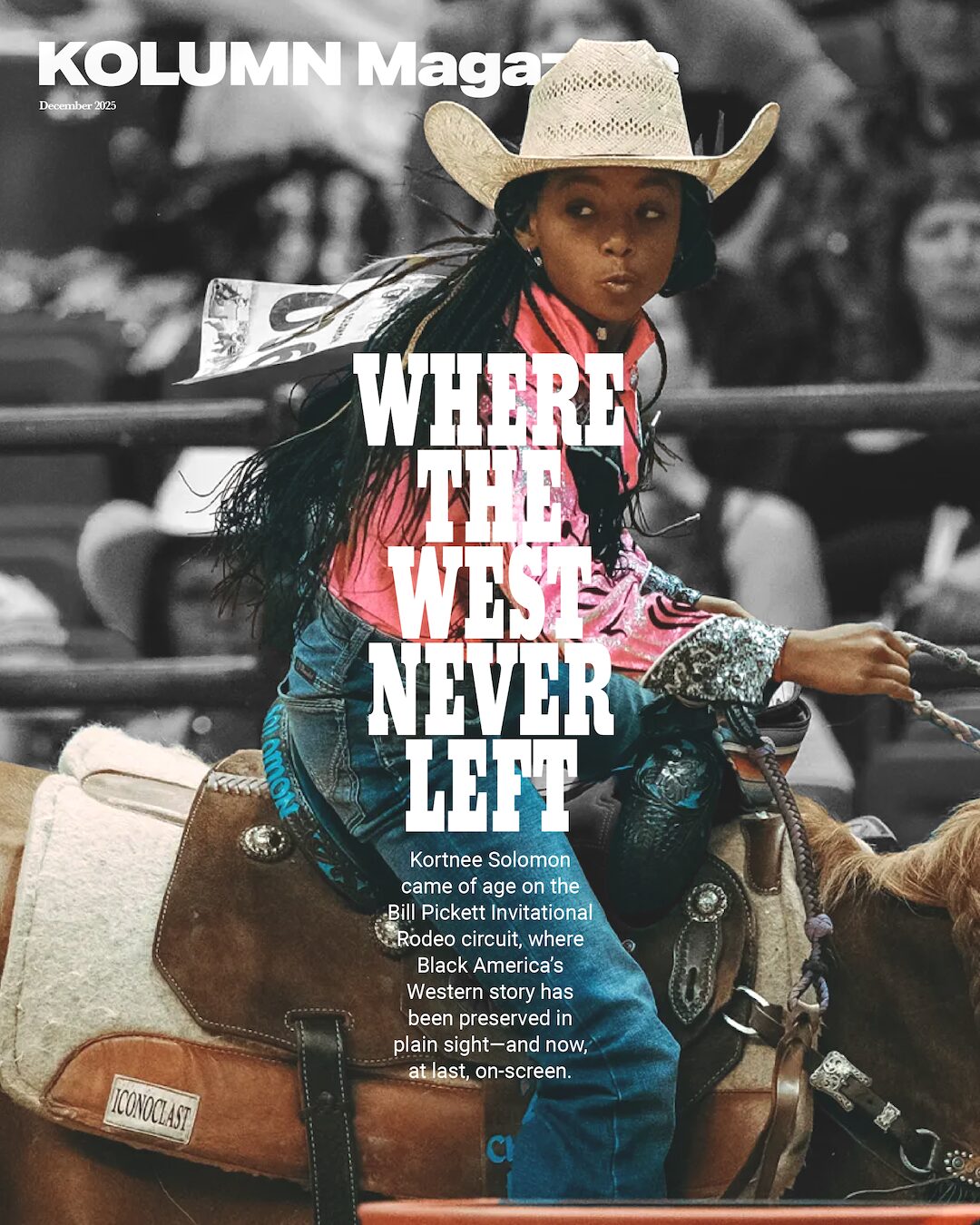

But rodeo does not behave like a headline, and neither does the career of Kortnee Solomon—whose reputation, even as a teenager, is rooted less in symbolism than in the unglamorous mechanics of the sport: the early hours, the hauling, the split-second decisions that happen before the crowd understands what it just saw.

The public story most Americans encountered began in June 2021, when the Bill Pickett Invitational Rodeo’s (BPIR) “Showdown in Vegas” aired on CBS—described as the first Black rodeo to air on national broadcast television—after a partnership with Professional Bull Riders helped bring the event to a larger platform. In that broadcast orbit, Solomon became an emblem of a larger, long-suppressed truth: Black cowboys and cowgirls have always been part of the American West, even when the mainstream West—film, advertising, certain corners of country music—preferred them invisible.

Yet Solomon’s actual career has always been less about arrival than about continuity. She is, as many profiles have captured, a fourth-generation Texas cowgirl who debuted at the Bill Pickett Invitational Rodeo at age five, and who competes in ladies’ barrel racing and junior breakaway roping—events that reward precision, speed, and composure more than bravado. What distinguishes her is not merely the milestone but the infrastructure that undergirds it: a family that treats rodeo as an inheritance and a daily practice; a circuit that functions as both sport and cultural archive; and a contemporary moment that is finally, slowly widening the frame.

The lineage that makes a “first” possible

Solomon’s biography is dense with names because the sport itself is dense with kinship. Her mother, Kanesha Jackson, is frequently described as an 11-time invitational champion; her father, Cory Solomon, as a Professional Rodeo Cowboys Association (PRCA) tie-down roper; her grandmother, Stephanie Haynes, as an 18-time champion and a board member of the Bill Pickett Invitational Rodeo; her late grandfather, Sedgwick Haynes, as the rodeo’s former general manager.

This isn’t ornamental family background. In rodeo—especially the Black rodeo tradition that the Bill Pickett circuit has toured and protected since the 1980s—lineage is often a training program. The family doesn’t just “support” the athlete; it manufactures the conditions under which an athlete can exist. Horses require land, feed, veterinary care, tack, time, hauling. A young competitor requires coaching, travel, and the kind of calm adult presence that turns nerves into routine.

Profiles of the family emphasize that Solomon and her mother care for their horses at home—feeding, grooming, training, riding—tasks that define the rhythm of rodeo life more than any buckle does. In other words: before a child becomes a symbol, she becomes a stable hand.

And that matters because Solomon’s “first” can be misunderstood if it’s treated as sudden. It wasn’t. It was cultivated—through a family ecosystem that treated rodeo as normal, not novelty, and through a Black rodeo circuit that long served as a parallel institution when other doors were narrower.

The circuit: Why Bill Pickett matters to her career

The Bill Pickett Invitational Rodeo is often described as the oldest or longest-running touring Black rodeo circuit in the United States—founded in 1984 by Lu Vason and later led by Valeria Howard-Cunningham after his death. Its origin story is inseparable from a critique: Vason observed a lack of Black competitors and a lack of public knowledge about Black Western history, and he built an institution meant to educate and entertain while centering Black rodeo athletes.

That framing—sport as competition, and sport as preservation—helps explain why Solomon’s career is routinely narrated through BPIR rather than through the mainstream circuits that dominate cable packages. BPIR is the place she debuted; it is the stage where her family’s dominance carries weight; it is also the environment where a young Black girl can be “just another competitor,” rather than a constant exception.

When the Professional Bull Riders (PBR) partnership led to the 2021 broadcast moment, BPIR leaders described it as the culmination of a long effort to achieve visibility and opportunity. The point was not only spectacle; it was infrastructure—media exposure that can translate into sponsorship, resources, and a wider funnel of future competitors.

For Solomon’s career, that matters in a very practical way. Barrel racing and breakaway roping—particularly for youth—require an investment that is hard to maintain without support. Visibility can become funding. Funding can become horses, hauling, entry fees, time. Time becomes reps. Reps become speed. Speed becomes wins. Rodeo, at its best, is a loop.

The work inside the events: barrels and breakaway

Solomon’s two primary reported events—barrel racing and junior breakaway—are, in different ways, tests of synchronization.

Barrel racing is a high-speed pattern: horse and rider sprint into the arena, wrap three barrels in a cloverleaf, and run out. It looks like pure speed, but it is actually an argument between acceleration and control—a negotiation with a half-ton animal whose balance you must protect while shaving fractions of a second.

Breakaway roping, meanwhile, is an event where time is everything and violence is minimized: the rider ropes a calf, and when the rope pulls tight, the string attached to the saddle horn breaks—signaling the end of the run. It’s a sport of timing, tracking, and technique; the smallest mistake is loud on a stopwatch.

In reported coverage of the 2021 Vegas event, Solomon is described preparing mentally before her run—seeking quiet and focusing on what she intends to execute. That detail reads small until you recognize what rodeo demands of a child: the ability to create stillness in a loud arena; the ability to perform a plan in seconds; the ability to lose publicly, reset quickly, and do it again in a different town.

The “first” that isn’t just hers

When Solomon is introduced as “the first Black cowgirl to compete in a nationally televised rodeo,” the temptation is to locate the meaning solely in her body: her age, her race, her singularity.

But “firsts” in sport are usually group achievements that happen to be embodied by one person. In Solomon’s case, the “first” is also the result of BPIR’s institutional persistence, the PBR partnership’s broadcast leverage, and a broader cultural moment in which Black Western stories are receiving a more serious hearing.

It is also, crucially, the result of women—especially Black women—holding the infrastructure together. Recent coverage of BPIR has emphasized leadership by Valeria Howard-Cunningham and coalitions of women elders who preserve the circuit’s continuity and public presence. In other words: Solomon’s career is not merely a story of youth excellence. It’s a story of what happens when an ecosystem refuses to disappear.

The long arc: Black rodeo as lived history

One of the more honest ways to understand Solomon’s career is to treat it as a chapter in a much older narrative: Black rodeo culture as both sport and cultural survival.

The BPIR is named for Bill Pickett, the legendary Black cowboy and rodeo figure credited with pioneering “bulldogging” (steer wrestling) and whose legacy is routinely cited as evidence that Black innovation shaped the sport from its early days. The circuit’s very existence is an argument against the myth that Western heritage is exclusively white.

This is why major fashion and culture outlets have been drawn to BPIR—not only because it is visually rich, but because it exposes how incomplete the mainstream story has been. Vogue, for example, has described BPIR as the longest-running traveling Black rodeo in the U.S., emphasizing both competition and cultural expression, including women’s events and youth support.

Solomon emerges from that environment: a place where Blackness in the arena is not a novelty but an assumption—where the Western story is not something you audition for, but something you inherit.

Visibility, and what it costs

Television changes a sport, but it also changes the athlete.

When BPIR reached CBS in 2021, the broadcast was scheduled on Juneteenth, explicitly tying the milestone to a national commemoration of emancipation and to a broader educational effort. That timing gave the moment historical resonance. It also set the table for a familiar pressure: the athlete as representative.

A teenager can carry that expectation lightly—until she can’t. The “first” becomes a brand; the brand becomes a demand; the demand can swallow the sport.

Yet, in the reporting that exists, Solomon is repeatedly framed not as someone burdened by the symbolism, but as someone oriented toward competition itself—toward the simple challenge of running her race against older riders and male athletes. That framing matters because it insists on her athletic identity first.

There is also another kind of cost: the economic reality of rodeo. Horses are expensive; injuries are common; travel is constant. Photographers and chroniclers of Black rodeo culture have noted the fragility of participation in the face of rising costs and barriers. Solomon’s visibility—like BPIR’s—can be understood as a bid for sustainability as much as celebration.

The culture around her: Style, confidence, and belonging

Rodeo is performance in more ways than one. The fashion—hats, boots, rhinestones, pressed jeans, custom shirts—is not mere decoration; it is a language of pride and place. In Black rodeo spaces, that language often carries additional meaning: it signals belonging in a world that historically denied it.

One reason Solomon’s story has traveled widely is that it punctures a lingering stereotype: that “cowgirl” is a white category. In 2024, Simone Biles publicly amplified Solomon’s accomplishment, writing that she once wanted to be a cowgirl but was told Black cowgirls didn’t exist—an anecdote that captured, in miniature, the cultural erasure Solomon’s visibility confronts.

That endorsement didn’t make Solomon a rodeo athlete. It made a broader public briefly aware that she already was one—and that the country’s assumptions were the thing that needed catching up.

Photography and the making of a modern myth

Solomon’s career has also been shaped by a specific kind of attention: documentary photography that treats Black rodeo as contemporary life rather than retro curiosity.

Andscape’s 2021 feature is framed through the work of photographer Ivan McClellan, who has documented Black cowboys and cowgirls for years and followed Solomon’s path to the Vegas event. This matters because photography does more than illustrate; it archives. It asserts that the subject is real, present, and worthy of serious artistic record.

That impulse has only grown. McClellan’s broader project on Black rodeo culture has been profiled internationally, including in The Guardian, which described his attraction to the fusion of street style, music, and Western tradition in Black rodeo environments—and his commitment to documenting a community too often erased.

For Solomon, this kind of chronicling creates an unusual form of stability: a record. In sports where athletes can disappear from the public eye between seasons, documentation becomes a kind of continuity—proof that the story didn’t begin at the moment television noticed.

What her career signals—without reducing her to a symbol

If you step back and treat Solomon’s career as a case study rather than a fairy tale, several implications become clear:

First: Talent in rodeo is often a family project. Solomon’s reported lineage—champion mother, professional father, champion grandmother—illustrates how excellence is transmitted through coaching, access, and repetition.

Second: Institutions matter. BPIR’s history—founded in 1984, sustained through decades, and finally reaching network television—shows how parallel institutions can preserve talent until the mainstream is ready (or forced) to widen its lens.

Third: Representation is not a vibe; it’s a resource. Television exposure, media attention, and cultural endorsements can translate into sponsorship and opportunity, which are essential in a sport where the cost of participation is a gatekeeper.

Fourth: The West is not a museum. Solomon’s story lands now—amid renewed debate about who belongs in “country” and “Western”—because it demonstrates the West as contemporary, diverse, and still contested terrain.

And finally: Solomon’s career is not a single moment. It is a trajectory. The more honest question is not “What did she represent on television?” but “What does she do next—and what resources does the sport provide so that she can keep doing it?”

The future that depends on the present

Rodeo careers are notoriously hard to project. Horses get injured. Families move. Money tightens. Interests shift. For youth athletes, adolescence can be a cliff: the moment when talent is either funded into maturity or forced into a different life.

Yet Solomon’s advantage—beyond skill—is that she is not alone. Her career sits inside a multi-generational architecture built to keep riders riding. It is the kind of architecture BPIR itself has tried to provide at scale: a touring home for Black rodeo athletes, a cultural platform, and now, intermittently, a media product with national reach.

If the sport—and the broader culture—treat Solomon as merely a story they once consumed, then the moment becomes a souvenir. If they treat her as an athlete in an ecosystem worth sustaining, then the moment becomes what it should have been all along: a beginning.