By KOLUMN Magazine

It was a seasonally cold Sunday afternoon when I took the elevator up to the second floor of Parlor OKC, the kind of cold that makes you want something hearty but not heavy, something familiar but not dull. Oklahoma City has a way of sharpening appetite in winter—wind cutting through Automobile Alley, sunlight slanting low between brick buildings that once sold cars and now sell experiences. The visit was not accidental. I was there on recommendation, the best kind: the sort that arrives without qualifiers, offered by someone whose taste has already been proven reliable.

Parlor OKC, at 11 NE 6th Street, bills itself as a marketplace eatery, a food hall designed to host a broad scope of regional and ethnic favorites under one roof. It does. But food halls, for all their variety, can blur together after a while—carefully branded stalls, clever menus, crowds orbiting novelty. What distinguishes a place inside a food hall is not just what it serves, but how it makes you feel the moment you arrive.

At Monte’s Gourmet Dogs, what you feel first is welcome.

This is not metaphorical. It is literal. Monte Williamson, Oklahoma native, founder, and namesake, does not stand behind his counter as a distant operator. He greets. He listens. He remembers. The interaction is quick, unforced, and unmistakably sincere. Within minutes, it becomes clear that the visit is memorable for two equally important reasons: Monte himself, and Monte’s culinary imagination.

The food is the draw. The man is the glue.

Monte learned the art of casual cuisine—and the equally important art of making people feel immediately at ease—working at his father’s side from the age of thirteen. That detail is not decorative. It explains everything. In family-run restaurants, especially in Black-owned casual dining spaces, children often absorb lessons that go far beyond recipes: how to read a room, how to pace service, how to talk to strangers until they no longer feel like strangers. Monte did that work early, six days a week, and it shows.

Even the logo tells the story. Monte’s Gourmet Dogs features an illustration of Monte at thirteen years old—a likeness he still keeps on his phone, not as nostalgia, but as proof. Proof of where this began. Proof of continuity. Proof that the work has always been personal.

The conversation before the food

Our discussion moved quickly, a rapid accounting of a life’s journey compressed into a few minutes: childhood, years in automotive sales, the pivot toward Monte’s Gourmet Dogs. There was no rehearsed pitch, no branding monologue. It felt more like the way barbers talk while cutting hair—facts delivered in passing, confidence built on repetition rather than performance.

This is important, because it frames the food correctly. Monte’s Gourmet Dogs is not an idea first and a kitchen second. It is the opposite. It is lived experience rendered edible.

If readers take only two things from this story, they should be these: first, meet Monte. Second, remember two words—Gator Étouffée. Not to be confused with Special Ed’s “Alligator Soufflé,” and not to be treated lightly.

No one—and we repeat, no one—in the history of Hotdogdom is doing this better.

Upstairs, but grounded

Monte’s Gourmet Dogs occupies its space on the second floor of Parlor without apology. Food halls can sometimes flatten identity, turning distinct businesses into interchangeable stalls. Monte’s resists that flattening by leaning into clarity. You know what is being sold. You know who is selling it. You know why it exists.

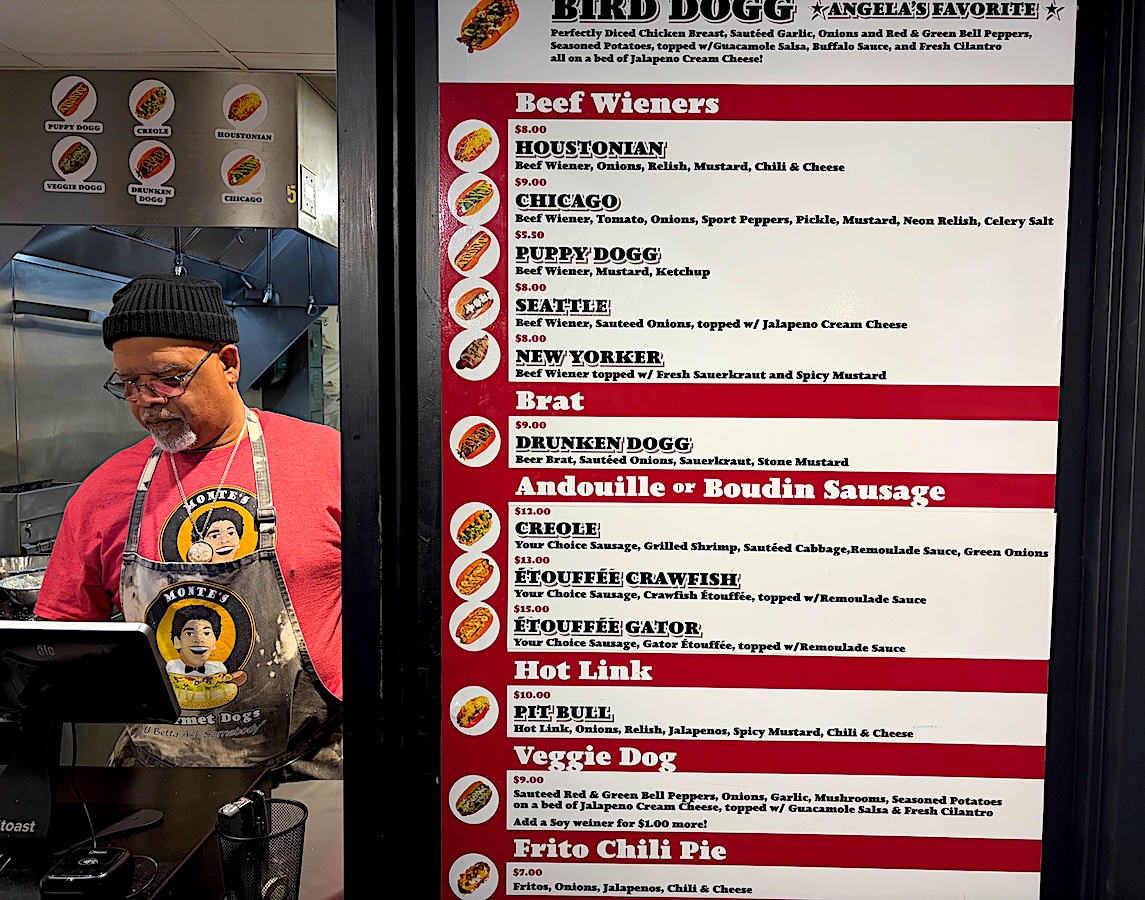

The menu is legible without being boring. It respects tradition while leaving room for invention. It understands that a hot dog is not a joke—it is a cultural object with enough elasticity to carry both nostalgia and risk.

There are familiar anchors:

The New Yorker: All-beef wiener, fresh sauerkraut, spicy mustard. Clean, sharp, unapologetic.

The Houstonian Dogg: Beef wiener, onions, relish, mustard, chili, cheese—a Southern sprawl contained in a bun.

The Chicago Dogg: Beef wiener, tomato, onions, sport peppers, pickle, mustard, neon relish, celery salt—a respectful nod to dog orthodoxy.

Big Thunder Dogg: A name that signals abundance before you even see it.

Then there are the items that reveal Monte’s imagination at full stretch:

Bird Dogg: Perfectly seasoned diced chicken; sautéed red and green bell peppers, onions, and garlic; seasoned potatoes; guacamole salsa; buffalo sauce; cilantro; all resting on a bed of jalapeño cream cheese.

Creole Dogg: Andouille sausage, grilled shrimp, sautéed cabbage, remoulade sauce, green onions.

And finally, the dish that bends the entire visit toward itself:

Gator ÉTOUFFÉE — available on a roll or in a bowl.

Before the spoon, the aroma

The Gator Étouffée announces itself before it is seen, before it is tasted, before the mechanics of eating even begin. There is a moment—brief but unmistakable—when the bowl is set down and the scent reaches you first, carrying with it a kind of authority. This is not the aggressive hit of spice meant to impress from across the room. It is deeper than that. Rounder. It moves slowly, unfolding in layers, the way dishes built on patience always do.

You register the base immediately: a savory warmth that suggests time spent at the stove, the gradual coaxing of flavor rather than the shortcut of heat alone. There is richness, but not heaviness. You sense roux without seeing it—its nutty undertone woven into the aroma rather than sitting on top of it. This is the smell of something that has been stirred deliberately, watched carefully, adjusted by instinct rather than measurement.

What follows is spice—not sharp, not confrontational, but confident. The blend is balanced in a way that feels practiced, almost private, as if the seasoning mix were never meant to be explained out loud. You can tell that nothing here is accidental. Each element knows its role. There is warmth, yes, but it arrives gradually, blooming rather than striking. It invites rather than challenges. The kind of spice that does not ask whether you can handle it, because it assumes you can.

Only after that do you notice the sweetness underneath, subtle and grounding. It comes from the aromatics—onion softened into translucence, perhaps bell pepper reduced to essence rather than texture. These notes do not compete with the spice; they steady it. They provide the counterweight that keeps the dish from tipping into excess. This is the difference between food that is seasoned and food that is understood.

Before your hand touches the spoon, your body has already begun to prepare. Saliva gathers. Attention narrows. Conversation pauses. This is a physiological response, one you cannot fake or force. It is the body recognizing nourishment that goes beyond calories. The étouffée smells like it will satisfy something specific.

Watching Monte prepare it, you begin to understand why. There is no hesitation in his movement, no checking of notes, no second-guessing. The process looks automatic, but it is not careless. It is what happens when repetition has burned knowledge into muscle memory. This is not a recipe he follows; it is one he inhabits. His hands move as if the steps have been rehearsed for decades, because in many ways they have—first beside his father, later on his own.

This matters. Étouffée is not a dish that tolerates uncertainty. It exposes shortcuts immediately. Too much heat and the spices turn bitter. Too little and the base collapses into blandness. Overcook the protein and it toughens, undercook it and it feels unfinished. Monte’s preparation avoids all of these traps because it is guided by feel rather than fear.

The gator itself contributes to the aroma in a quiet way. It does not dominate. Instead, it absorbs, carrying the surrounding flavors without pushing back. There is a faint, clean scent to it—almost neutral—that allows the étouffée to remain the star. This restraint is intentional. In lesser hands, gator becomes spectacle. Here, it becomes structure.

By the time you finally lift the spoon, the experience is already half complete. The aroma has done its work. Expectations have been set—not artificially inflated, but grounded. You are not bracing for surprise. You are anticipating confirmation.

And when the first bite comes, it delivers exactly what the aroma promised.

Bowl or roll: two philosophies, one truth

Served in a bowl, the Gator Étouffée settles into jasmine rice, onions and green onions offering sweetness and bite, remoulade cutting through richness at exactly the right moments. The bowl is contemplative food. You sit. You slow down. You notice texture. You listen to the room around you.

On a roll, the same étouffée becomes something else entirely. Portable. Immediate. Almost mischievous. The bun reframes the dish as street food, the kind of thing you might eat standing up, leaning against a rail, wondering how something this indulgent ended up in your hands.

Both versions work. That is the test. One does not diminish the other. Instead, they reveal two sides of the same idea: that comfort food does not have to choose between seriousness and pleasure.

Why the hot dog still matters here

In American food culture, the hot dog has always been underestimated. Associated with ballparks and backyard grills, it is often treated as a lowest-common-denominator meal. Monte’s Gourmet Dogs rejects that framing without rejecting the hot dog’s soul.

A hot dog is, at heart, democratic food. It is meant to be eaten among people. It invites conversation. It tolerates customization. It belongs to everyone. Monte understands this intuitively. His menu does not mock tradition; it extends it.

The Creole Dogg works because shrimp, cabbage, and remoulade have a shared logic. The Bird Dogg works because it respects contrast—heat against cream, crunch against softness. The classics work because Monte does not overthink them.

And the étouffée works because it is not there to impress you. It is there to feed you well.

Hospitality as the hidden ingredient

What elevates Monte’s Gourmet Dogs beyond strong execution is hospitality. This is not an abstract concept. It is visible in posture, tone, timing. Monte moves with ease between greeting customers, answering questions, and cooking. There is no rush in his demeanor, even when the line grows.

This matters in a city like Oklahoma City, where dining culture has increasingly leaned toward polish and spectacle. Monte’s reminds you that warmth does not require theater. Sometimes it just requires showing up as yourself.

The cold outside fades. The room feels smaller, friendlier. You begin to notice that other customers are smiling, gesturing toward their food, telling companions what to order next time. Monte’s creates advocates not by asking, but by delivering.

The legacy beneath the counter

To understand Monte’s Gourmet Dogs as merely a clever food concept is to miss what is most durable about it. The real structure holding the business together does not sit on the menu board or in the brand mark. It rests beneath the counter, in a lineage of labor that began long before Parlor OKC existed—long before food halls became shorthand for urban renewal, long before “gourmet” attached itself to everyday foods as a marketing strategy.

Monte Williamson’s earliest training did not come from culinary school or staged kitchens. It came from proximity. From standing close enough to his father at Elmer’s Burger Barn, opened in 1977, to absorb not just technique but temperament. Working six days a week from the age of thirteen is not simply a detail to admire; it is a formative environment. At that age, repetition becomes worldview. You learn what consistency looks like not as a theory, but as survival. Doors must open on time. Food must taste the same on a slow Tuesday as it does on a packed Saturday. Customers return not because you dazzled them once, but because you respected them every time.

Family restaurants teach a particular kind of accountability. There is no buffer between effort and outcome. If something goes wrong, it is personal. If something goes right, it is communal. Monte learned early that food is not separate from relationship—that the person on the other side of the counter is not an abstract “customer,” but someone who has chosen to trust you with their appetite, their money, and often their limited time.

That lesson echoes throughout Monte’s Gourmet Dogs. You feel it in the way Monte speaks to people—not performative friendliness, but recognition. You feel it in the pacing of service, the refusal to rush even when the line grows. You feel it in the confidence to stand behind food that does not need explanation because it has already been tested by real people, over real time.

There is also the matter of continuity. Elmer’s Burger Barn belonged to a different era of Black entrepreneurship, one shaped by necessity as much as ambition. These were businesses built to serve their communities when options were limited, when representation in mainstream dining spaces was rare, when ownership itself was an act of resistance. Monte’s work inherits that history without replicating it wholesale. Instead, it adapts.

His years in automotive sales—often mentioned briefly, almost as a detour—are actually part of the same arc. Selling cars teaches you how to read people quickly. It teaches patience, persuasion, and restraint. It teaches when to talk and when to listen. Those skills translate seamlessly into food service, where the exchange is faster but no less human. Monte does not upsell. He guides. He suggests. He lets curiosity do the work.

The logo—Monte depicted at thirteen—anchors the entire enterprise in that truth. It is not branding nostalgia. It is accountability made visual. Every day, the business answers to that younger version of himself, the one who learned that showing up mattered more than being seen. That image reminds customers, even subconsciously, that this place was not engineered backward from a trend. It grew forward from lived experience.

In a city where redevelopment often threatens to erase the past even as it celebrates progress, Monte’s Gourmet Dogs operates as a quiet counterargument. It proves that legacy does not have to be preserved behind glass. It can be cooked. It can be served. It can evolve without forgetting its origin.

What sits beneath the counter, then, is not just memory. It is method. It is the accumulated knowledge of how to feed people well and treat them better. It is the understanding that casual food still deserves care, that joy can be deliberate, that excellence does not require distance.

This is why Monte’s works. Not because it reinvents the hot dog, but because it respects the work that made reinvention possible.

Leaving changed, if only slightly

When you leave Parlor, stepping back into the cold afternoon, you carry more than a satisfied appetite. You carry a recommendation forming in your mouth. You think about who you’ll bring next time. You rehearse how you’ll describe the étouffée without overselling it.

This is how local institutions are built—not through hype cycles, but through repetition. Through Sundays like this one. Through bowls and buns that deliver exactly what they promise.

Monte’s Gourmet Dogs does not ask to be taken seriously. It earns seriousness by caring deeply about something simple.

Meet Monte. Remember the gator étouffée. Everything else will take care of itself.