KOLUMN Magazine

The

Midnight

That Never Ended

From stolen gatherings in cane breaks to Freedom’s Eve services that count down to liberation, the Black church’s oldest ritual may be its most contemporary one.

By KOLUMN Magazine

The hush harbor: A sanctuary built out of risk

On certain nights in the antebellum South, the world narrowed to the practical dimensions of danger. A path through trees. A hollow. A stand of cane thick enough to swallow sound. The air carrying what it carried—crickets, damp soil, the afterwork fatigue of bodies that had already given the day away. And then, if the night held, the smallest decisions became existential: where to step, how loudly to breathe, whether a child could be trusted not to cry, whether a song could be trusted not to travel.

This was not church as architecture. It was church as a set of evasive maneuvers.

Historians and folklorists have called these gatherings “hush harbors” (or “hush arbors”), secret worship sites where enslaved African Americans met outside white supervision. The phrase itself feels like a contradiction—harbor suggests safety, hush admits the cost of seeking it. The hush harbor was both refuge and evidence: proof that enslaved people, denied control over their labor, their mobility, their families, and their literacy, still insisted on controlling something else—their interior lives, their moral imagination, their relationship to a high authority, and their relationship to one another.

The popular image is pastoral: a ring of worshippers in the woods, heads bowed, hands lifted, song rising softly. That image is not wrong, but it can become too calm if you don’t keep the stakes in frame. These meetings were criminalized by the logic of slavery even when they weren’t explicitly outlawed: enslavers understood that unsupervised assembly made room for comparison (“Is your master as cruel as mine?”), for planning, for coded communication, for the emergence of leaders, for a shared story in which bondage was not a natural order but a moral scandal. It is difficult to overstate what a threat collective interpretation posed to a system built on unilateral interpretation.

The hush harbor belonged to what scholar Albert J. Raboteau famously framed as the “invisible institution”—the hidden religious life of enslaved people that existed alongside, beneath, and in direct opposition to plantation Christianity. In white-controlled services, the Bible could be deployed as management, emphasizing obedience and submission; in the hush harbor, the Bible could be reread as a map out of captivity—Exodus as a promise, not a metaphor. The same text, in other words, could be made to serve two masters, and enslaved people knew the difference.

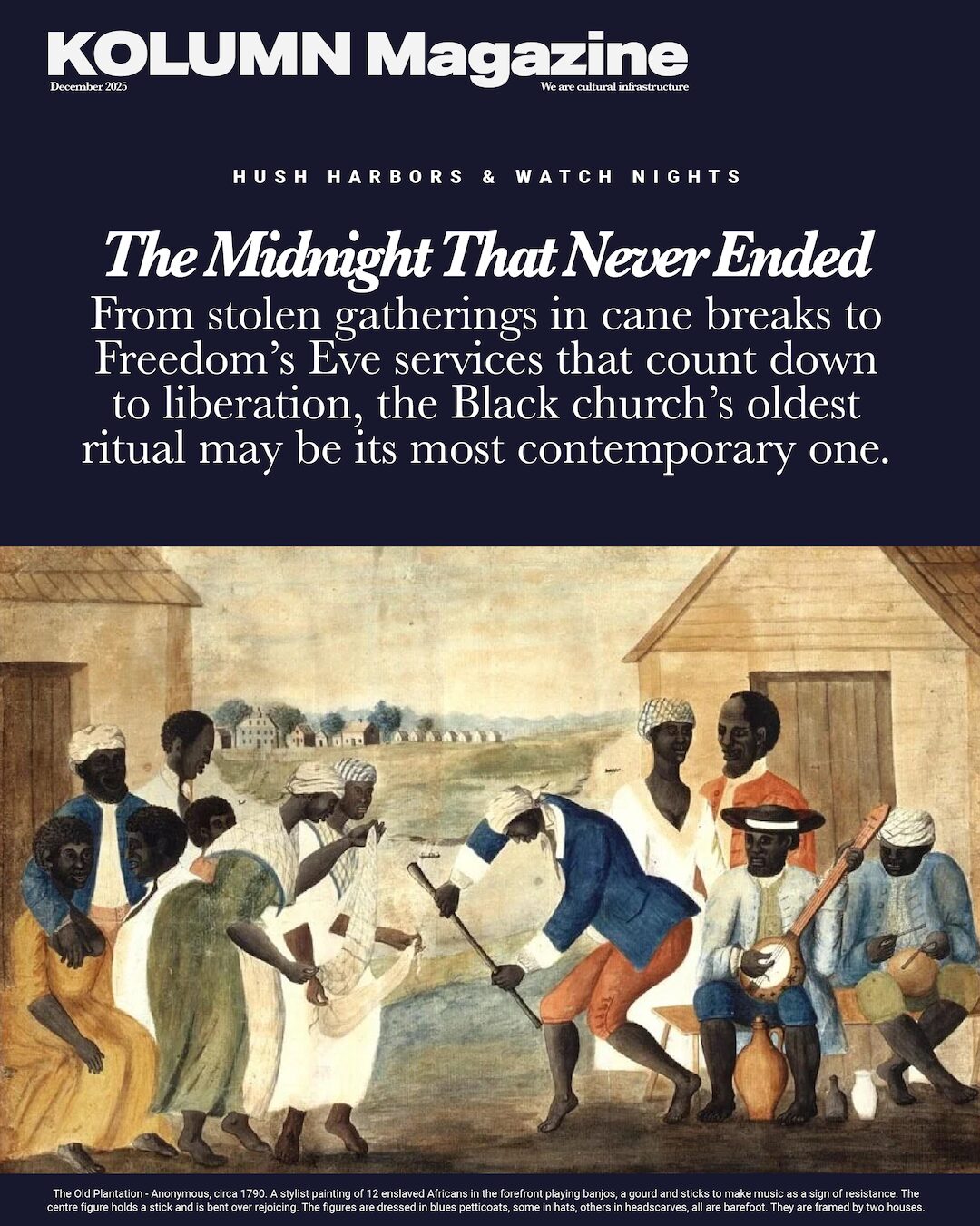

The practices inside the hush harbor were neither purely African nor purely European American; they were, more accurately, adaptive—shaped by memory and necessity. Enslaved people blended African-derived rhythms, movement, call-and-response, and ecstatic expression with Christian theology and hymnody, producing an idiom that would become foundational to Black religious culture in the United States. Scholars and public historians consistently point to the hush harbor as an incubator for the spirituals: songs that could carry a double payload—devotion on the surface, strategy underneath; heaven in one register, freedom in another.

Even the logistics of worship were an education in collective care. Someone watched the perimeter. Someone carried news—who was restless, who was drinking, who was known to curry favor with the overseer. Someone decided whether the group would meet in the same place twice (often it wouldn’t). Someone moderated volume, not for reverence but for survival. In some accounts and retellings, worshippers used wet cloth hung on branches to dampen sound—an improvised acoustic technology born out of the simplest political requirement: do not be heard.

The hush harbor also functioned as a school without paper and pencil. It trained people in leadership and ritual. It trained them in persuasion. It trained them in the emotional grammar of testimony—how to name suffering without collapsing under it, how to speak hope without sounding naïve, how to locate oneself inside a larger story. That kind of training mattered later, after emancipation, when Black communities built formal congregations and denominational infrastructure. The hidden church became, in time, a visible one—sometimes literally “children of the hush harbor,” as preservationists and historians describe the line from clandestine woodland worship to independent Black churches fighting to survive and be remembered.

It is tempting to treat the hush harbor as prelude—moving, important, but ultimately replaced by sanctuaries with pews and steeples. But the hush harbor was not merely a workaround until freedom arrived. It was a theory of freedom practiced in miniature: autonomy carved from surveillance; community assembled under threat; a future believed into being on nights when the present offered little evidence for belief.

And it is here—inside that theory, inside that habit of gathering at risk, inside that discipline of waiting—that the lineage to Watch Night engendered a greater significance. (updated to acknowledge the full historic arc of Watch Night)

From hush to watch: How a secret church invented a public ritual

Watch Night, in many Black churches, is often described today as a New Year’s Eve service—prayer, music, testimony, and the turning of the calendar marked with religious seriousness. Its roots, however, were grounded prior to the anticipated emancipation of enslaved Africans in the mid 18th century. The Moravian Church (1727) embraced a faith-oriented alternative to celebrations marked by revelry, with a focus on penitence, faithfulness, and commitment to God. Churchgoers met the transition of the year as a moment of renewal, framed by hymn, scripture, prayer and a lovefeast. (updated to acknowledge the full historic arc of Watch Night)

In the Black American tradition, Watch Night is not simply about a new year. It is about a particular night: December 31, 1862—“Freedom’s Eve”—when enslaved and free Black people gathered to watch and wait for the Emancipation Proclamation to take effect at midnight on January 1, 1863. The habit of staying awake became a form of collective vigilance: a people listening for a legal thunderclap that might—or might not—change their lives.

If the hush harbor taught a people how to worship without being heard, Watch Night asked them to worship while being fully conscious of time.

This is the bridge: hush is the technology of survival under slavery; watch is the technology of survival at slavery’s edge. One is about concealment, the other about anticipation. Both are about thresholds—between captivity and imagined deliverance, between fear and courage, between the night as danger and the night as possibility.

The Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture describes Watch Night as an annual tradition braided with “memory of slavery and freedom,” faith, reflection, and community—an observance that holds the story of emancipation inside the ticking seconds of December 31. Britannica similarly notes the service’s New Year’s Eve placement and its association, in many African American churches, with remembrance of the Emancipation Proclamation.

But to grasp why this annual service endured, you have to hold two truths at once.

First: the Emancipation Proclamation did not instantly free all enslaved people everywhere. It declared freedom for enslaved people in Confederate states in rebellion, and its enforcement depended on Union military victory and presence—meaning freedom arrived unevenly, contested, and often violently resisted. Even so, the proclamation functioned as a moral and political pivot: a declaration that slavery was no longer simply a “state issue” but a target of federal war policy, and that Black freedom had moved closer to the center of American history.

Second: enslaved people understood law as something that could be delayed, distorted, or denied. They had lived under a legal regime that defined them as property, that recognized contracts about their bodies but not their marriages, that policed their movement and punished literacy. So when a law promising freedom approached, the watching was never passive. It was tense, embodied, vigilant. It carried the memory of promises broken.

That posture—the suspicion of easy deliverance—has always been part of the Black church’s spiritual intelligence.

Consider how Watch Night emerges almost as a formalization of hush-harbor instincts. In a hush harbor, someone always kept watch, because the meeting itself was illicit. On Freedom’s Eve, the act of watching expanded from the perimeter to the horizon: not merely “Is the overseer coming?” but “Is the world changing?” The surveillance of slavery had trained Black people to be alert. Watch Night repurposed that alertness into liturgy.

And once you see that, you can see why Watch Night remains so resilient as a tradition: it does not require naïveté about America. It does not insist that freedom arrives cleanly, on schedule, without backlash. Instead it builds a service around the hardest spiritual task in a country that keeps postponing its own ideals: waiting without surrendering.

Journalists and historians have repeatedly returned to the specificity of the original Watch Night. The Associated Press has described the tradition as rooted in gatherings on December 31, 1862, when Black Americans assembled in anticipation of emancipation’s legal turn at midnight, and notes how the observance continues in churches today in both in-person and virtual forms. The Root, writing in the present tense of cultural memory, frames Watch Night as a practice that reaches back to slavery and the Civil War, emphasizing the communal act of waiting for the Emancipation Proclamation’s enactment. Public institutions have also staged commemorations—Smithsonian programming has explicitly called Watch Night “Freedom’s Eve,” anchoring the ritual in historical memory rather than generic New Year optimism.

What gets lost in many modern summaries, though, is how the ritual also metabolizes the emotional history of New Year’s itself for enslaved people. Long before Freedom’s Eve, New Year’s Day could be associated with the sale and hiring out of enslaved labor—an annual cycle that threatened family separation and intensified dread. Over time, Freedom’s Eve complicated New Year’s with a counter-memory: the same calendar turn that had once signaled terror could also signal possibility. (This reversal, that genius for taking a wound and turning it into a ritual of endurance, is one of the Black church’s defining cultural technologies.)

So the relationship between hush harbors and Watch Night is not merely chronological (“first there were hush harbors, then there were churches”). It is conceptual:

Hush harbors taught a people how to gather under threat, how to code their hopes, how to create sacred space without permission.

Watch Night taught a people how to gather on a date—how to turn history into an annual appointment, how to rehearse emancipation even when the nation refuses to finish the job.

That is why Watch Night services often feel like more than services. They can feel like time machines—rooms full of people carrying two calendars at once: the civic calendar (December 31, January 1) and the Black historical calendar (bondage, emancipation, unfinished freedom). The midnight moment becomes a ritualized hinge between them.

And in that hinge, the hush harbor’s DNA is still detectable: testimony that sounds like survival; music that carries double meaning; the insistence that God is not the property of the powerful; and, above all, the idea that a community’s truest work may happen at night, when the world’s noise dies down enough for people to hear one another tell the truth.

The arc into the present: What Watch Night now carries, and what it still rehearses

If you walk into many Black churches on December 31 today, you may find a service that looks familiar in American Protestant terms—sermon, hymns, prayer, perhaps communion—but the emotional weather is different. It is part celebration, part inventory. It often includes what the Smithsonian describes as reflection on faith and community, and what other public histories frame as remembrance of slavery and freedom.

There is frequently a moment near midnight when the congregation becomes acutely aware of time: the counting down, the collective inhale, the pause. In some churches, the Emancipation Proclamation is read aloud as a ritual text—an annual re-enactment of the historical turning point, echoing the tradition noted in reporting on Watch Night commemorations connected to the National Archives and Black church practice. In others, the proclamation functions more as backdrop than script: the service gestures toward freedom with songs and prayers that refuse to reduce liberation to a single document.

This variety is itself part of the tradition’s modern maturity. Watch Night is not a museum piece. It is a living service that adapts to a congregation’s needs.

Yet the throughline from hush harbor to Watch Night persists in at least four ways.

1) Vigilance as spiritual practice

The hush harbor required vigilance for immediate survival. Watch Night requires vigilance for moral survival. In a country where civil rights gains can be followed by backlash, where economic vulnerability can be generational, where violence can feel cyclical, the idea of “watching” becomes a theological posture: staying awake to reality. The AP notes contemporary Watch Night services as a symbol not only of historical emancipation but of perseverance and community amid present-day challenges.

2) Memory as protection

In slavery, memory could be dangerous—remembering Africa, remembering kin, remembering dignity. But it could also be protective, a way to keep a self from being fully colonized by captivity. Watch Night turns memory outward and communal. It insists that the story of emancipation is not optional knowledge; it is a shared inheritance. Institutions like NMAAHC explicitly frame Watch Night as memory work—an annual return to the history of slavery and freedom.

3) Music as coded language

Spirituals and later gospel traditions carry forward the hush harbor’s musical architecture: call-and-response, improvisation, testimony embedded in melody. Even when there is no explicit “code” in modern worship, the tradition still speaks in layered meanings—songs about Jordan and Canaan that can be heard as heaven and as justice, as personal salvation and collective liberation. Scholarship on enslaved worship consistently connects hidden gatherings to the formation of these expressive traditions.

4) The creation of “safe space” as a radical act

A hush harbor was a safe space carved from a hostile world. Watch Night remains, for many, a safe space carved from a hostile year. It is where grief can be named, where endurance can be honored, where hope can be spoken without being mocked for its audacity.

That last point is important because it explains why Watch Night is still relevant even for people who do not experience it primarily as a Civil War commemoration. For some congregations, the service has expanded to include prayers for violence victims, for the sick, for the unemployed, for political sanity, for children. During the COVID era, for example, mainstream reporting noted cancellations and adaptations of Watch Night gatherings while still identifying the observance’s meaning in the Black church as tied to emancipation memory. A tradition that began with waiting for freedom has had to practice waiting for other forms of deliverance, too.

And yet, the most honest Watch Night services do not offer cheap catharsis. They tell the truth about emancipation’s limits even as they honor its importance. They acknowledge what history has proved: that freedom can be declared and still contested; that law can change and still be undermined; that deliverance can arrive and still require defense.

This realism is not cynicism. It is inheritance.

Because the hush harbor was never sentimental. It was faith under conditions designed to annihilate faith. Its people did not gather in the woods because they enjoyed secrecy; they gathered because secrecy was the price of spiritual self-possession. They learned to sing softly not because quiet was holy but because quiet was protective. They learned to trust one another in increments, to build community as a practiced skill, to treat the night as both threat and shelter.

Watch Night preserves these lessons in a new form. It takes the hush harbor’s clandestine urgency and turns it into an annual public rite. It says: we will gather anyway; we will tell the story anyway; we will keep watch anyway; we will mark time ourselves.

What makes this arc so distinctly Black American is that it turns oppression’s constraints into cultural form. The enslavers feared the unsupervised gathering; the gathering became the seed of independent Black religious institutions. The enslavers feared the sound of prayer; the prayer became music that remade American culture. The enslavers feared the night; the night became a calendar ritual that now belongs to the Black church as surely as Sunday morning.

In that sense, Watch Night is not simply the descendant of hush harbors. It is their translation. The woods became sanctuaries; the wet cloth became walls; the lookout became the deacon at the door; the coded spiritual became the gospel song that still carries history in its bones. The old discipline—listen, watch, endure—did not disappear when the church got keys and a mortgage. It simply found a new time slot.

Midnight, after all, is still the hour when a community can hear itself think.

And if you want the deepest continuity—deeper than any specific hymn or tradition—it may be this: both hush harbors and Watch Night insist that freedom is not merely a political status but a practice. You practice it by gathering. By remembering. By testifying. By telling the truth about the world as it is, and then staying up anyway, as if the world might still change.

Because once you have lived through a history where dawn was never guaranteed, you learn to honor the people who watched for it—together.

Editor’s Note

This article draws on a wide body of historical scholarship, archival material, and contemporary journalism to trace the lineage between hush harbors—clandestine worship gatherings among enslaved African people in the United States—and the enduring Watch Night tradition in Black churches.

Foundational historical framing is informed by the work of scholars such as Albert J. Raboteau and Sterling Stuckey, whose research on enslaved religious life and the “invisible institution” remains central to understanding faith as both survival strategy and cultural resistance. Primary perspectives are further supported by enslaved people’s narratives preserved through the Library of Congress and Works Progress Administration archives.

Public history resources from the National Museum of African American History and Culture and the Smithsonian Institution provide contemporary interpretation of hush harbors, Freedom’s Eve, and Watch Night as living traditions rooted in slavery and emancipation. Documentation related to the Emancipation Proclamation and its historical impact is drawn from the National Archives.

Contextual reporting and cultural analysis from The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Guardian, Associated Press, Ebony Magazine, The Root, and Word In Black situates these traditions within both historical memory and present-day Black religious life.

Together, these sources affirm Watch Night not as a symbolic New Year’s observance, but as a ritual inheritance—one shaped in secrecy, sustained through emancipation, and carried forward as a collective act of remembrance, vigilance, and faith.