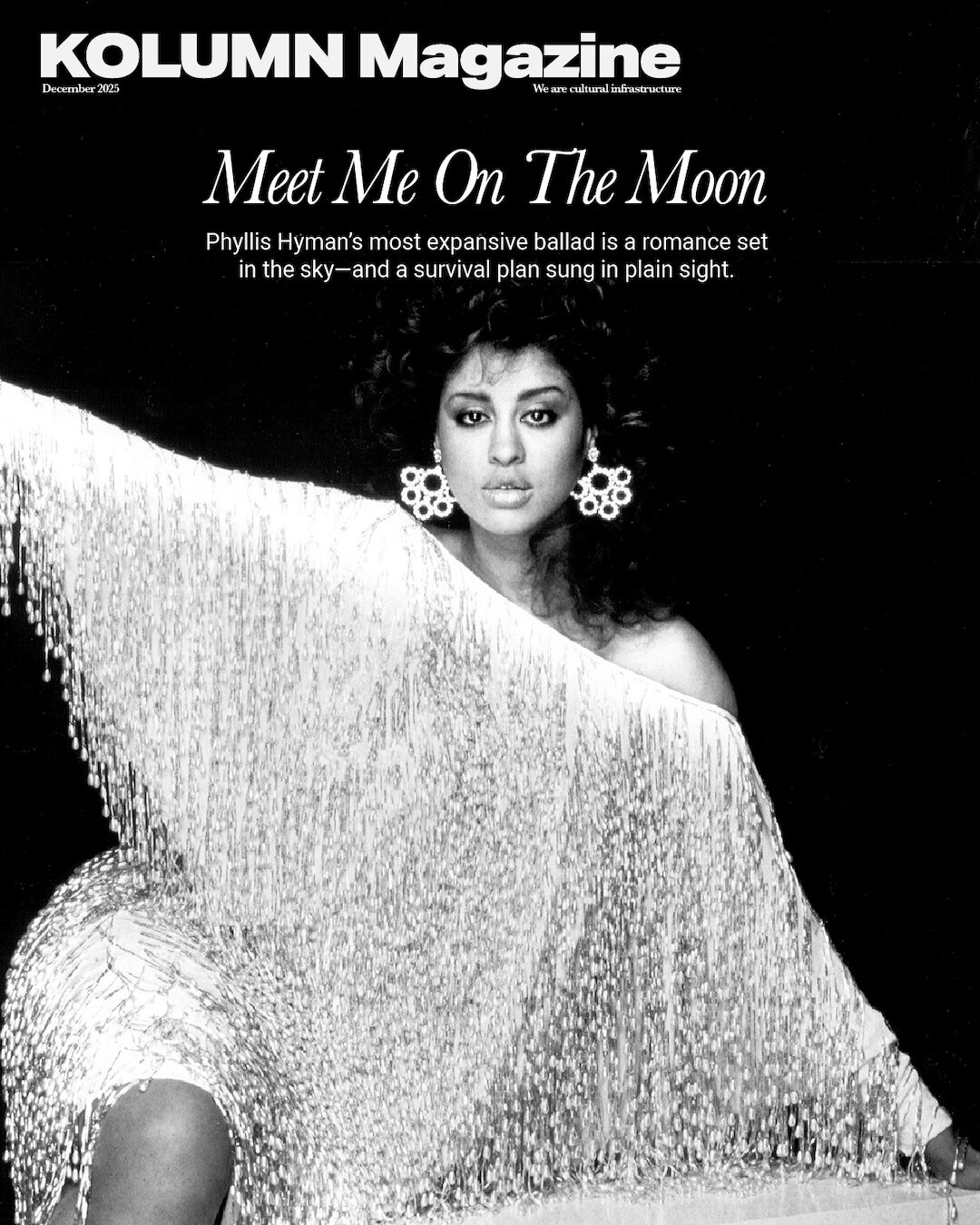

KOLUMN Magazine

By KOLUMN Magazine

The invitation: “Soon as you can,” before the world catches you

The first thing “Meet Me on the Moon” tells you is that it has no interest in smallness. It begins as an invitation—simple language, almost childlike in its promise of a place “in the middle of the sky”—and then refuses to hurry. At 6:42, it’s long by early-1990s R&B standards, especially for a track tucked near the end of an album meant to sell a contemporary, radio-facing version of Phyllis Hyman.

That album, Prime of My Life (1991), is often described as her commercial peak: it yielded her only No. 1 R&B single (“Don’t Wanna Change the World”), and it arrived under the Philadelphia International banner—an institution built on sophistication, aspiration, and a certain kind of grown Black glamour. The cruel irony is that Hyman’s life did not consistently match the poise of the brand. Accounts of her biography describe years of bipolar disorder and depression, cycles of substance use, and a steady sense that the industry loved her voice while withholding the kind of validation and stability she wanted—especially the elusive “pop” breakthrough.

“Meet Me on the Moon,” written by Gene McDaniels and Carrie Thompson, sits in that tension. On the surface, it is a romantic fantasy—clouds, breezes, an “everlasting moment.” Underneath, it plays like a private negotiating document: if you cannot give me peace here, then meet me somewhere else. That “somewhere else” matters. Hyman doesn’t ask to be met at a club, a corner, a home, or a hotel room. She asks to be met off the map.

This is where the song’s reputation inside Black listening culture begins: not merely as a ballad, but as a location—an emotional room people return to when they want tenderness without humiliation. It is also where the song’s industry reputation begins: as a showcase for a vocalist whose intelligence is inseparable from her instrument. When Billboard later listed it among the great Philadelphia International songs, it framed the track’s power as a kind of surgical focus—“all about one note,” delivered late in the performance like a revelation rather than a stunt.

And yet, to talk about the “note” without talking about the life is to misunderstand why “Meet Me on the Moon” endures. Hyman’s struggles are not a footnote to the record; they are the gravity that makes its moonlight feel earned.

The architecture of a slow-burn: structure, pacing, and the “one-note” thesis

“Meet Me on the Moon” is built less like a conventional radio ballad and more like a short film with a long closing shot. Its most important structural choice is time: the song gives itself the room to stage emotion rather than simply declare it. That matters because Hyman is a singer whose gift is not only the sound of her contralto, but the way she parcels information—how she makes a lyric feel newly dangerous by delaying it half a second, or newly tender by softening a consonant.

The track’s credits underscore that intention. It is not presented as a novelty add-on; it has a full production identity on Prime of My Life, with detailed album documentation listing its writers and engineering, the same way a label treats a serious composition. The runtime—again, 6:42—signals that we are entering a performance designed for narrative development: opening scene, gradual escalation, climax, denouement.

Structurally, you can hear three broad movements:

1) The proposition (opening minutes): The lyric introduces the moon as refuge—clouds as furniture, sky as privacy. Hyman’s approach here is deliberately controlled. She does not spend her emotional capital early. She sings with the measured clarity of someone making terms, not making a fuss.

2) The widening (middle stretch): The arrangement opens out; the phrasing lengthens; her tone grows warmer and more insistent. This is where the song’s musicality does its real work. Rather than piling on melisma, Hyman relies on dynamic shading—tiny increases in volume and density that make the fantasy feel less like decoration and more like need.

3) The arrival (late climax and coda): This is where the “one note” idea becomes legible. Billboard’s description—“It’s all about one note, mostly,” arriving deep into the runtime—captures a truth about how the track engineers catharsis: not by constant escalation, but by withholding the most dramatic sustained moment until the listener is already fully inside the story. In other words, the song uses restraint as suspense.

What makes this musical architecture feel uniquely Hyman is the way it mirrors her public persona: elegance first, intensity underneath, and then—only when you’ve earned it—the full force of the instrument. Later critical retrospectives pick up on that emotional design, describing the album’s balladry as both beautiful and difficult, with “Meet Me on the Moon” carrying a sense of farewell that’s heightened by what we now know of Hyman’s life.

To listen closely is to hear that this is not just a love song about escape. It is a composition that treats escape as a craft problem: How do you build a door in the air? Answer: with pacing, with breath, with a melody that refuses to rush its own truth.

The industry’s mirror: Philadelphia International, critical framing, and “underappreciated” as a business category

There is a particular kind of praise the music industry gives singers like Phyllis Hyman—prestigious, reverent, and often quietly limiting. It sounds like: peers respect her, connoisseurs adore her, a vocalist’s vocalist. The compliment carries a trap: it implies a small audience, a niche carved out of sophistication rather than mass demand. Hyman lived inside that tension for years, and by the time Prime of My Life arrived, the tension had hardened into a storyline.

The Guardian’s account of the women of Philadelphia International is explicit about this dynamic. It frames Hyman as the label’s final artist—highly respected by peers and by Black audiences—while noting that the lack of a major pop hit “gnawed” at her and fed a sense of being undervalued. Jean Carn, in that piece, recalls seeing Hyman’s mood swings and describes the waste of her death in language that reads like both grief and indictment.

The Washington Post, reporting later in 1995, gives the most granular portrait of the machinery around her final years—how slow periods between work aggravated depression, how friends believed steady employment might have saved her, and how Hyman’s frustration with “not meritorious attention” and not being “honored” as an artist became part of her daily emotional weather. This is the industry context in which “Meet Me on the Moon” should be understood: not as a random deep cut, but as a record made by a woman who knew exactly how quickly the business could go quiet.

And yet, the same industry did recognize the album’s craft in real time. Trade-facing commentary on Prime of My Life routinely singled out its longer, moodier performances as the project’s core—tracks that function as emotional epics rather than singles. “Meet Me on the Moon” appears repeatedly in retrospectives and curated lists of Philadelphia International’s catalog, positioned as a pinnacle cut—an example of the label’s late-era elegance and Hyman’s singular interpretive power.

What’s striking is how the industry’s praise tends to focus on technique—notes, control, length, the seriousness of the performance—while Hyman’s own story, and the public record of her mental health struggles, suggests she wanted something more elemental: to be seen as central, not supplemental. The song’s fantasy—“meet me” somewhere unreachable by ordinary demands—reads, in that light, like an artist imagining a world where her value is not up for debate.

Industry praise can be a mirror. Sometimes it reflects brilliance. Sometimes it reflects the limits placed on where brilliance is allowed to live.

“Black audiences kept her”: community praise, afterlives, and why this song functions like a gathering place

If the industry talked about Phyllis Hyman in the language of prestige, Black listeners often talked about her in the language of use. Not “Is she great?” but “What does this do to you?” That difference is why “Meet Me on the Moon” has become more than a track title in Black American music culture; it is a shorthand for a specific emotional register—grown tenderness, unshowy intimacy, a softness that doesn’t apologize for needing space.

You can see that living, communal relationship to the song in the ecosystem that keeps it circulating long after 1991. Contemporary R&B and soul platforms continue to frame “Meet Me on the Moon” as a classic—not merely as nostalgia, but as evidence of how Hyman’s artistry holds up against shifting production eras. SoulTracks, introducing a modern cover of the song, explicitly treats Hyman’s original as a benchmark performance. Retrospectives around the Prime of My Life anniversary describe the record as autobiographical in its emotional temperature and single out “Meet Me on the Moon” for its solace and its ache—beautiful, but not easy.

Then there’s the informal archive: fan communities, social posts, and comment threads where people trade favorite Hyman songs like heirlooms. These aren’t academic citations; they are evidence of a public that refuses to let her be reduced to “underappreciated.” In Facebook groups and other social spaces dedicated to classic soul, “Meet Me on the Moon” appears again and again in lists of favorites and “best of” debates—less as a deep cut and more as a personal anthem people assume others will recognize. That kind of repetition is how canon is made in the community: not by awards, but by return visits.

What does the community hear in this song? Many listeners describe the track as a sanctuary—an imagined place where longing doesn’t have to perform toughness. In a culture that often demands Black women be invulnerable, Hyman’s voice offers vulnerability without spectacle. She does not “confess” in the tabloid sense; she composes feeling, giving it structure and dignity. That is part of why the song’s length matters to fans. It grants time—time to sit inside the feeling, time to be changed by it, time to let the performance do what shorter songs won’t: carry you all the way through.

And the throughline of struggle sharpens that bond. The widely reported details of Hyman’s death—her note, her scheduled Apollo performance, the exhaustion implied by the words “I’m tired”—have become part of how audiences interpret her catalog, even when they try not to impose tragedy onto every lyric. Community praise often holds both truths at once: the joy of the voice and the grief that the voice did not protect its owner.

In that sense, “Meet Me on the Moon” is not only a love song. It is a meeting place—where Black listeners go to honor beauty, and to mourn what beauty cost.

The throughline of struggle: what the moonlight can’t erase, and why the song still feels like testimony

There is a temptation, when writing about an artist who died by suicide, to treat every masterpiece as foreshadowing. That’s not journalism; it’s retroactive mythmaking. “Meet Me on the Moon” does not “predict” Phyllis Hyman’s end. It does something more complicated, and more honest: it reveals the method by which she lived—how she translated distress into design, loneliness into phrasing, self-doubt into a kind of severe elegance.

The public record makes clear that Hyman’s struggles were long-running and multifaceted. Accounts in major coverage describe depression and mood swings witnessed by peers, and a deep frustration with how she was valued by the industry—respected, yes, but not celebrated in the mainstream way she craved. The Washington Post’s reporting on her final period is especially stark about the relationship between work scarcity and despair, quoting those close to her who believed that being “not working” intensified her depression and hopelessness.

Against that context, “Meet Me on the Moon” reads as a record about control—because control is what you reach for when your mind and your circumstances refuse to cooperate. The song’s structure, with its measured opening and its delayed peak, can be heard as a composer’s and vocalist’s insistence: I will decide when the emotion arrives. The late, sustained climactic moment singled out by Billboard—this idea that the track’s power concentrates into one defining note deep into the runtime—functions like a metaphor for endurance. She holds back, she holds steady, she holds on—until holding becomes the point.

But the song’s fantasy also reveals what control cannot solve. The moon is not just romance; it’s distance. It’s a place far enough away that the ordinary rules—industry expectations, bodily scrutiny, the relentlessness of being “on,” the private swings of mood—might not reach. The lyric imagines a softness so total it becomes weather: clouds like bedding, breezes like permission. The arrangement supports that imagery by refusing sharp edges; it favors glide, warmth, and gradual intensification. And then Hyman complicates the softness with her tone: she never sounds naïve. She sounds like someone who has learned exactly how fragile peace can be.

This is why the song’s afterlife is inseparable from her biography, even when listeners resist making tragedy the center. When Hyman died on June 30, 1995—hours before she was scheduled to perform at the Apollo—news accounts noted the note she left behind, repeating the phrase “I’m tired.” It is difficult, knowing that, not to hear exhaustion in the way she asks to be met “soon as you can.” Yet the ethical move is not to turn the lyric into evidence; it is to recognize the artistry as the thing she controlled best.

“Meet Me on the Moon” endures because it is both engineered and intimate: a rigorously paced composition that still feels like a private phone call. It holds the paradox of Phyllis Hyman: a woman praised for sophistication, embraced by Black audiences, and still, too often, left to fight alone. The moon in the song is not a prophecy. It is a wish—and, for six minutes and forty-two seconds, a place she makes real.