KOLUMN Magazine

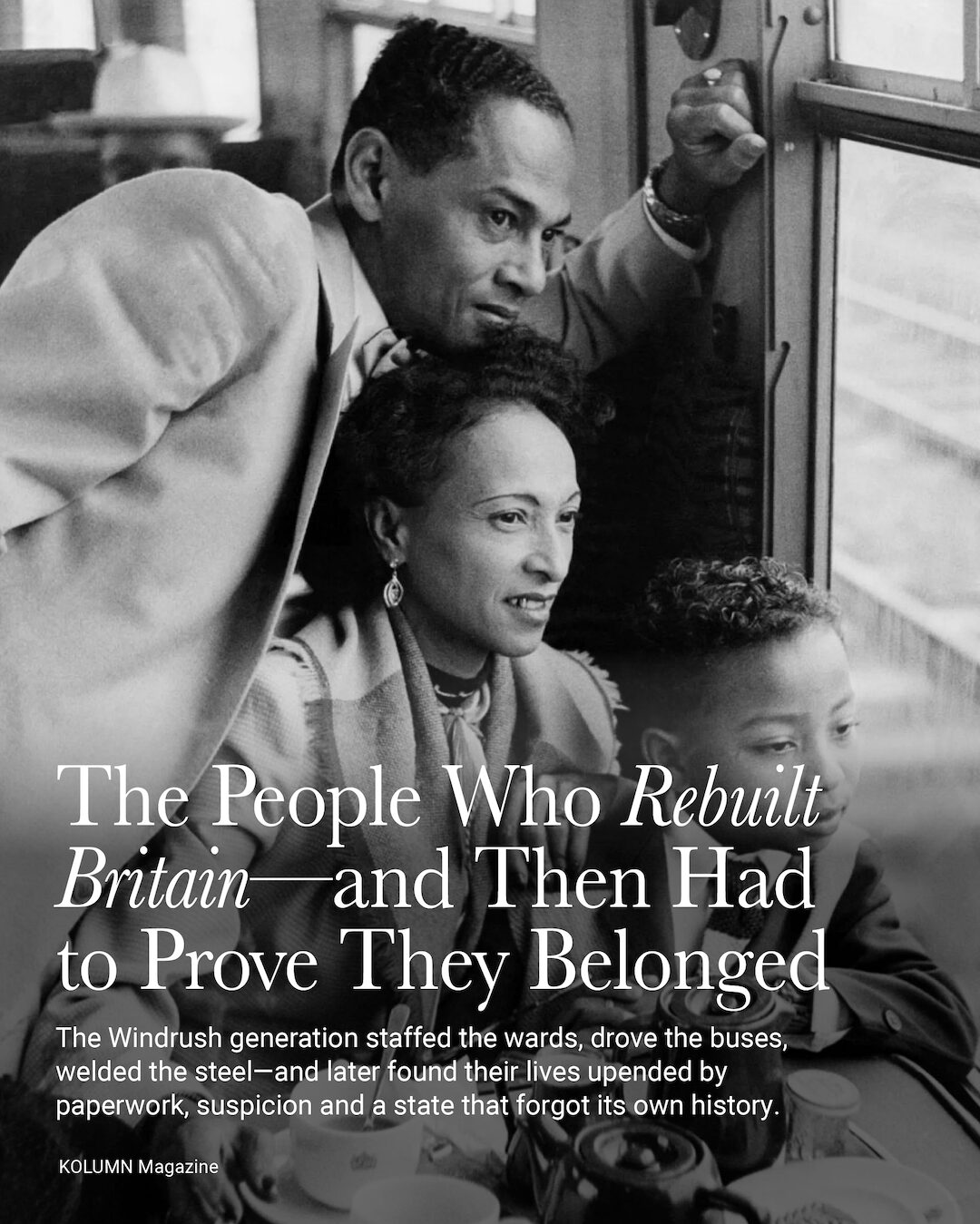

The People

Who Rebuilt Britain—and Then Had to Prove They Belonged

The Windrush Generation staffed the wards, drove the buses, welded the steel—and later found their lives upended by paperwork, suspicion and a state that forgot its own history.

By KOLUMN Magazine

The Empire Windrush carried a few hundred Caribbean passengers—some ex-servicemen, some clerks, some apprentices, some simply young enough to believe that the “Mother Country” was more than an idea printed on schoolbooks and stamped onto passports. They came legally, as British subjects, into a nation that both needed them and did not quite know what to do with them. The postwar state was expanding; the labor market was thin. Britain required hands for the work of rebuilding—hands for the wards, the rail depots, the bus garages, the factories, the foundries. The migrants would become, in a shorthand that arrived later, “the Windrush generation,” generally understood as those who emigrated from the Caribbean to the U.K. between 1948 and 1973.

Yet the story—told properly—does not begin and end at the dock. It begins again in cramped rooms above shops and in boarding houses with rules posted like scripture: No Blacks. No Irish. No Dogs. It begins at hiring windows where “labour shortage” meant “you can apply,” and “colour bar” meant “not here, not that job, not the front.” The U.K. National Archives’ educational materials describe how migrants often faced a “colour bar” that blocked access to work and accommodation, pushing many into jobs beneath their qualifications.

It also begins—quietly, intimately—at the bank counter.

Because rebuilding a life is not only a matter of wages. It is a matter of what you can do with those wages: where you can deposit them, how you can send money home, whether you can borrow, whether you can insure, whether you can buy a house, whether a clerk treats you like a customer or a suspect. Work and money, in postwar Britain, were inseparable from belonging. For the Windrush generation, the country’s need for labor was real; so was its resistance to Black presence. And for many, the most consequential fights were not only in the streets or Parliament, but in the ordinary institutions that decide who gets to build wealth—employers, landlords, and yes, banks.

The overlap: Britain’s postwar labor map as a Caribbean network

If you want to understand Windrush as economics rather than sentiment, start with the overlaps.

In the years after 1948, Britain’s expanding public services and industry created large, centralized workplaces—places where Caribbean migrants were recruited, trained, slotted into shifts, promoted slowly (if at all), and concentrated in specific roles. That concentration produced two things at once: exploitation and community.

The U.K. government’s own Windrush guidance summarizes the sectors where Caribbean migrants commonly found work: construction, public transport, factories and manufacturing—and, for many women, the NHS as nurses and nursing aides. The National Archives similarly notes the postwar need to fill jobs in the health service, transport and the postal system.

These weren’t abstract categories. They were buildings and timetables, uniforms and pay packets.

A young man from Jamaica might start at a London bus garage, learning routes the way one learns a new city: by repetition, by getting lost, by listening. A Trinidadian woman might train as a nurse in a hospital where half the night staff seemed to share an accent and a story about leaving home. A Barbadian machinist might find himself at a Birmingham plant where the Caribbean presence became a parallel institution: an informal placement agency, a union caucus, a rumor mill, a lifeline. Birmingham museums’ historical materials note that many settled there and worked in manufacturing and the NHS—another sign of how concentrated, and thus overlapping, these pathways became.

Overlaps mattered for the simplest reason: they shaped who met whom.

A hospital ward was not just a workplace; it was a social engine. Nurses recruited friends. Porters introduced cousins to supervisors. A bus driver’s flatmate worked nights at the post office. Someone’s aunt took in lodgers—often new arrivals—who needed an address to apply for jobs, and then needed a job to keep the address. In these loops, the Windrush generation built an internal labor market within the national one.

But the overlaps also made racism legible. When dozens of Caribbean workers occupy the same ranks—nursing aide, cleaner, driver, foundry hand—and remain there for years, patterns appear. Migrants learned quickly which jobs “took Black workers” and which did not; they learned which landlords rented and which smiled and lied; they learned what “no vacancies” sounded like in different boroughs.

It’s worth pausing on the timeframe. The Windrush era spanned decades, but the first Race Relations Act did not arrive until 1965; before then, discrimination could be direct and unapologetic. That lag matters, because it means the foundational period—when people chose careers, accumulated experience, tried to buy homes—was also the period when bias was largely legal, customary, and often explicit.

The result was a particular kind of British integration: Caribbean migrants were essential, visible, and still treated as provisional.

The work that made the state run: NHS corridors and the economy of care

In the official story Britain tells itself about the postwar decades, the National Health Service appears almost as a moral weather system: it arrives, it changes the climate, it becomes the background against which modern British life plays out. In the Windrush story, the NHS is less weather than architecture—an institution built fast, understaffed from the start, and kept upright by people who learned to live inside it.

By 1948—its founding year—the NHS already faced a staggering shortage of nursing staff. One public-history analysis of NHS records notes roughly 54,000 nursing vacancies in 1948, and describes how by 1949 the Ministries of Health and Labour, working with the Colonial Office and professional nursing bodies, were actively recruiting Caribbean women to fill gaps across nursing, auxiliary, and domestic roles. The language of the time was often careful, managerial, bureaucratic. The reality was blunt: there were too many beds and not enough hands. The empire, in practice, became a labor pipeline.

Recruitment was not a rumor; it was organized. Windrush Day’s own historical feature on Caribbean women and the NHS describes energetic campaigns—senior British nurses traveling to the colonies, selection committees operating in multiple British territories, and the Caribbean supplying a major share of recruits during that period. This is where the overlapping careers begin to look less like coincidence and more like design. When hiring is centralized and channeled through official networks, people arrive into the same corridors, the same training schools, the same staff hostels, the same night shifts—concentrated, visible, and essential.

A hospital in the 1950s and ’60s was an ecosystem with rules so strict they could feel religious: who spoke to the consultant, who called the matron, who was “promising,” who was “reliable,” who should be kept in the job that required endurance rather than authority. Caribbean women entered an institution that needed them, and then learned—often quickly—that need did not automatically translate into esteem.

They worked the wards and the back corridors, the oxygen-heavy rooms and the laundry-heavy basements. In some hospitals, Caribbean nurses and aides became the dependable engine of night duty: the shift when the building changes character, when the pace slows and the loneliness grows, when the staff are fewer and the work—turning patients, changing dressings, watching monitors, catching early signs of deterioration—requires alertness that is almost a second language.

Their contribution is sometimes described as “care,” which can sound sentimental, soft-edged, insufficiently economic. But care is labor. It is payroll. It is workforce capacity. It is the difference between a health system that functions and one that fails. In postwar Britain, the NHS’s promise of universal care depended on staffing, and staffing depended in part on Caribbean migration on a scale large enough to be described—without exaggeration—as structural.

The overlap is visible in the way a single hospital could become a Caribbean map. People from Jamaica, Barbados, Trinidad, St. Lucia—sometimes clustered by recruitment cohorts, sometimes by informal networks—found one another in dining halls and stairwells, in the shared geography of breaks taken too quickly. A new recruit learned not only how to take blood pressure, but also where to find hair products, which church held a Caribbean congregation, which bus route took you toward the rooms that would rent to you. The NHS did not merely employ Windrush migrants; it gathered them.

And because it gathered them, it made racism hard to hide.

Racism in the NHS was often delivered in the small ways institutions specialize in: assumptions about competence, “helpful” advice to keep ambitions modest, the steady narrowing of promotion. Patients could refuse a Black nurse; colleagues could make a joke and insist it was only a joke. Caribbean staff were frequently described as “hardworking” in a way that sounded like praise but operated as sorting—valued for stamina, not presumed to be leadership material. “Reliability” became a compliment that could also be a ceiling.

Outside the hospital, the racism followed them into housing and consumer life, shaping the economics of stability. In the early decades, discrimination in accommodation and employment was commonly described as a “colour bar”—a phrase that the National Archives uses to characterize barriers faced by migrants seeking jobs and housing in Britain in that era. A nurse might finish a shift at dawn and still spend her afternoon walking to viewings where the landlord’s face changed when he saw her, where a room was suddenly “taken,” where the posted rule—spoken aloud or implied—was that she did not belong in certain neighborhoods.

This is why the “economy of care” cannot be separated from the economy of finance. Regular NHS wages were a ladder, but the rungs depended on other institutions: a bank willing to open accounts without humiliating suspicion; a building society willing to consider a mortgage; an insurer willing to sell coverage without silently inflating risk. For many, “being a bank customer” was less about convenience than about status—proof that the country recognized you as economically real.

The overlapping careers in the NHS created overlapping financial behaviors. People saved together. They sent remittances together. They shared tips about which branches treated Caribbean customers with basic decency and which ones made you feel like you were requesting a favor rather than purchasing a service. When mainstream systems felt unreliable, some communities leaned on informal savings mechanisms and community finance to buffer the indignities and exclusions of the formal market.

There is also an irony, almost cruel in hindsight: hospitals generated documents—pay records, staff IDs, references—that should have anchored people’s paper identity. But the state’s recordkeeping, and the assumptions about who needed “proof,” were inconsistent. Many Windrush migrants—especially those who arrived as children on a parent’s passport—did not receive documentation that later policy would treat as essential. In other words: they labored for the state, inside the state’s most cherished institution, and later found the state demanding receipts for the privilege.

In the NHS corridors, the Windrush generation learned Britain’s paradox intimately: you can be indispensable without being secure.

Transport and industry: the mechanical heart of postwar Britain

If the NHS was the moral center of postwar Britain, transport and manufacturing were its mechanical heart.

Public transport—especially in large cities—was a classic entry sector: large employers, standardized recruitment, clear training, and perpetual need. Once again, overlap mattered. People arrived into friend networks already tethered to depots and garages; they joined shifts where Caribbean accents were common enough to feel like an alternative national radio.

Manufacturing and factory work followed similar logic. Britain’s mid-century economy still depended on industrial production at scale: metals, automobiles, food processing, textiles, consumer goods. Caribbean men and women filled night shifts, repetitive lines, dangerous tasks. They did so in a country that often treated them as labor first, neighbors never.

This was not merely “working-class history.” It was skilled labor too—welding, machining, electrical work, engineering support—frequently performed by people who had trained in the Caribbean or served in wartime units, only to be told they were “unqualified” when they arrived, forced into lower positions by the colour bar the National Archives describes.

To highlight “where and when careers overlapped,” you can picture it by decade:

Late 1940s–1950s: Entry into transport, hospitals, postal work; concentrated hiring in understaffed sectors.

1960s: Stabilization into long-term employment, union participation, attempts at home ownership; discrimination still pervasive even as race relations laws begin.

Early 1970s: The legal boundary approaches (1973 as a commonly cited cutoff for “Windrush generation” status); many families now established, children in British schools; immigration politics hardens.

These overlaps produced a shared Windrush professional culture: a way of talking about supervisors, a way of warning newcomers about landlords, a way of saving money collectively, a way of navigating institutions that demanded “proof” of respectability.

And this is where the bank counter enters the story not as a metaphor, but as a plot point.

“A customer is a status”: banking, remittances, and the early architecture of wealth

In many Windrush families, money moved in three directions at once: rent in Britain, remittances to the Caribbean, and savings for an eventual stake—often a home, sometimes a small business, sometimes education for children.

This required financial infrastructure. It required accounts. It required credit. It required insurance. It required, crucially, being regarded as financially legible.

Some migrants used informal savings clubs and community-based schemes when mainstream services felt inaccessible or unwelcoming—because discrimination was not only a matter of insult, but of product design and gatekeeping. A 2023 piece from Credit Union industry media (reflecting on community finance and Windrush) describes barriers such as financial exclusion and services designed around middle-class consumers, arguing that these dynamics shaped how Caribbean communities built alternative support structures.

Yet most people still had to deal with mainstream banks. Payday did not become wealth unless it could be stored safely, transferred reliably, and leveraged.

Banking, for Windrush, also intersected with identity in ways that would become devastating decades later. The point of being a “bank customer” is that your identity is supposed to be stable enough to attach money to. You are known. You have an account number. You have a record. For migrants who arrived as British subjects—often as children on a parent’s passport—official documentation was not always issued, and government recordkeeping could be weak.

In the early years, that weakness was hidden by daily life: you worked, you paid taxes, you raised children, you built credit in the informal way of regular employment. But the paper trail mattered more than many realized.

Windrush families often learned the logic of British respectability through finance: keep payslips, keep letters, keep receipts. Save. Don’t be late. Don’t attract attention. The irony is that later policy would demand precisely the kinds of documents ordinary people do not archive across decades—one official document for every year lived, according to advocacy accounts summarizing Home Office expectations.

Racism as policy: from the colour bar to the “hostile environment”

Britain’s Windrush story is often narrated as a moral error with a bureaucratic cause—something that happened because paperwork failed. But the deeper record shows something more deliberate: policy as a mechanism for deciding who is welcome, and on what terms.

Start with the uncomfortable clarity of the state’s own research. In 2024, the U.K. government published an independent report on the historical roots of the Windrush scandal. It states plainly that major immigration legislation in 1962, 1968 and 1971 was designed to reduce the proportion of people in the United Kingdom “who did not have white skin.” Reuters’ coverage of the report emphasized the same finding: that successive immigration and citizenship laws over decades aimed to restrict Black settlement and that the Windrush scandal flowed from this legacy.

This matters because it changes the question. The question is not “How did the system accidentally hurt citizens?” The question is “How did policy manufacture precarity for a population that was becoming politically inconvenient?”

The early “colour bar” was a social regime—informal but widespread—governing who could rent where, work where, be served where. The National Archives’ materials use the phrase to describe how migrants encountered discrimination in accommodation and employment, shaping where they could settle and what jobs they could access. It was the kind of racism that announces itself through everyday refusals.

But racism does not remain informal when a state decides it wants control. It becomes legislative.

Through the 1960s and early 1970s, immigration law tightened in ways that effectively reclassified Commonwealth migration—moving from a postwar assumption of shared imperial citizenship toward an increasingly policed boundary. The 2024 government report highlights these legislative milestones as part of a race-coded project of restriction.

At the same time, Britain began—slowly, imperfectly—to legislate against racial discrimination in public life. The first Race Relations Act arrived in 1965. The timing is revealing: restriction sharpened, while protections were late and partial. Britain was learning, in law, how to say two things at once: we can limit you, and we can condemn discrimination, without fully resolving the contradiction.

You can see that contradiction in a single emblematic episode: the Bristol Bus Boycott, where activists challenged the Bristol Omnibus Company’s discriminatory employment practices. In the Guardian’s obituary of Paul Stephenson—a pivotal figure in that movement—the paper describes how the company would hire Black and Asian workers only as cleaners, blocking them from better-paid roles like drivers and conductors, despite labor needs. This is the colour bar rendered as payroll architecture: you may work here, but only at the bottom; you may keep the system clean, but you may not steer it.

If the colour bar was the first gate, the later “hostile environment” was the conversion of gates into a nationwide operating system.

The phrase is associated with a 2012 moment, when then–Home Secretary Theresa May stated an aim to create a “really hostile environment for illegal migration”—a line frequently referenced in timelines of the policy’s development. But the genius—if you want to call it that—of the hostile environment was not rhetorical. It was administrative: the state outsourced border enforcement to everyday institutions.

Advocacy analyses describe how the hostile environment relied on measures that required employers, landlords, and service providers to check immigration status—transforming routine life into an ongoing verification exercise. A House of Lords Library briefing from 2018, prepared for a debate on the policy’s impact, likewise frames the hostile environment as an approach with serious consequences for people with lawful residency and employment rights.

The crucial mechanism was not a single deportation order. It was friction—introduced everywhere.

One widely discussed example is the Right to Rent scheme, which requires landlords to check immigration paperwork and penalizes renting to those without the “right” documents. Advocacy reporting points out the perverse incentive: landlords can minimize perceived risk by favoring those who look and sound like unquestioned citizens. In practice, a policy aimed at “illegal migration” becomes a policy that intensifies racial profiling in housing.

Now add the assignment’s central institutional actor: banks.

In the hostile environment era, financial life becomes a checkpoint. If you cannot open or keep a bank account, you struggle to be paid, to rent, to run a business, to build credit, to demonstrate stability. Banking becomes not merely a market service but an eligibility test. The border moves from the airport to the branch.

This is how the Windrush scandal becomes economically devastating, not only morally offensive. The people harmed were often long-settled residents who had worked for decades—frequently in public services like the NHS and transport—yet were asked to prove a status that the state itself had historically documented inconsistently, particularly for those who arrived as children. When proof becomes the currency, missing paperwork becomes a kind of poverty.

And this is what “policy racism” looks like in the modern state: not only exclusion from entry, but exclusion from infrastructure. You are made vulnerable not by a single act of force, but by the slow revocation of ordinary permissions—work, rent, healthcare, banking—permissions that together constitute a life.

Windrush, then, is not simply the story of Caribbean migration and British prejudice. It is the story of how a country can depend on a population’s labor while engineering that population’s insecurity—first through an informal colour bar, then through law, and finally through an administrative doctrine that turned daily life into a permanent border crossing.

The scandal as lived economics: job loss, housing loss, and the cruelty of “prove it”

When the Windrush scandal surfaced publicly in the late 2010s, many of the most wrenching stories were not abstract constitutional disputes. They were economic collapses triggered by bureaucratic denial: people losing jobs, being denied healthcare, being blocked from benefits, being threatened with removal.

The Windrush Lessons Learned Review (2020) described the human cost—jobs lost, lives uprooted—and criticized the failure to protect people who had every right to be in the U.K. Washington Post coverage in April 2018 captured how people who had lived in Britain for decades found themselves suddenly required to produce proof that the state itself often failed to provide.

In Britain, employment is not just income; it is documentation. If you lose the job, you lose the payslips, the reference letters, the employer attestation that becomes evidence. If you lose the home, you lose the address history. If your bank account is flagged, you lose the stability that makes everything else function. The “hostile environment” was hostile precisely because it targeted the scaffolding of ordinary life.

This is where the assignment’s demand—feature personal narratives of those who were bank customers—becomes more than a detail. In the scandal era, being a “bank customer” could become conditional on having the right documents; lacking them could make you unbanked, and being unbanked could make you unemployable, and being unemployable could make you deportable. The system formed a loop.

Overlapping careers, shared consequences: a composite of the Windrush workplace

Consider a composite portrait—built from the documented structure of Windrush labor pathways rather than a single named individual.

He arrives from Jamaica in the mid-1950s and takes a job in transport, because transport is hiring and because someone from his church knows a supervisor. She arrives from Barbados around the same time and trains for hospital work, because the NHS is hiring and because the training offers a stable path.

They do not meet at Tilbury. They meet years later, at a cousin’s wedding, because their working lives overlap socially even when not professionally. Their friends include a machinist in Birmingham manufacturing and a postal worker in London—sectors repeatedly identified as common landing zones.

They rent rooms, then a small flat. They open accounts. They send money home. They save—carefully—for a deposit. They learn which branches treat them coldly, which clerks call them “love” and still deny them. They join the great mid-century British project: work, tax, belong.

They also live through the tightening of immigration politics, the long delay before meaningful anti-discrimination enforcement, and the persistence of housing exclusion the National Archives calls a colour bar.

Decades later, when policies demand proof of status, their careers—so stable for so long—become vulnerabilities. The transport worker’s old employer has reorganized; records are scattered. The hospital worker has retired; her early documents are missing. The bank becomes not merely a place to store savings, but a place that may demand papers she never knew she needed to keep.

That is how overlapping careers become overlapping exposure. The very sectors that absorbed Caribbean workers—public services and large employers—also became conduits for policy enforcement once institutions were deputized to check status.

The long argument: Britain’s dependence and Britain’s denial

Windrush Day, held annually on 22 June, was introduced in 2018—an act of recognition arriving in the same era as the scandal’s most public harms. A country capable of ceremony was also capable of bureaucratic erasure. Both things can be true.

And the argument is not only historical; it remains administrative. In late 2025, the Guardian reported reforms to the Windrush Compensation Scheme aimed at accelerating payments and addressing long delays—changes prompted, in part, by the reality that many claimants had died while waiting. Other reporting described the government’s handling of the historical-roots report itself, including efforts to block its release and the political fallout.

These developments underscore a core truth: Windrush is not only memory. It is governance.

Britain’s postwar recovery depended on Caribbean labor in the NHS, transport, construction, manufacturing. Britain’s racial order constrained that labor’s rewards. And Britain’s later immigration regime—shaped by decades of racially discriminatory policy, as described in official research and summarized by Reuters—converted ordinary life into a paperwork test that many long-settled Black residents could fail through no fault of their own.

What the Windrush generation built

It can be tempting, in telling Windrush, to lean on the easy grammar of contribution: they gave so much. That is true, but imprecise. The more exact claim is this:

They built—materially and institutionally—parts of Britain that Britain now considers quintessentially British.

The NHS as an operational reality, staffed across roles.

Public transport as a functioning urban circulatory system.

Manufacturing and construction as postwar economic engines, run on shift work and skilled hands.

Community financial ecosystems that emerged in response to exclusion, helping families save, lend, and endure when mainstream systems failed to serve them well.

They also built political consequences: the very visibility of Caribbean Britain forced the nation to confront itself—sometimes through reform, sometimes through backlash, often through delay.

In the end, the Windrush generation’s story is not an “immigrant story” in the sentimental sense. It is a labor story, an institutional story, and a story about how citizenship is experienced in practice: at the job center, in the landlord’s hallway, at the police stop, and at the bank counter.

The ship arrived at Tilbury. The real arrival happened every day afterward—on the early bus to the depot, in the hospital corridor at 3 a.m., in the factory canteen, in the line at the branch where someone decided whether you were a customer or a problem.

That is what they contributed: work, yes—but also the forcing of a question Britain still struggles to answer. Who, exactly, gets to be “from here”?