KOLUMN Magazine

The Check

Is Coming.

The Damage Already Cashed

Inside Michigan’s Flint water settlement—why it took years to reach families, how fees and liens reshape “justice,” and what a majority-Black city is being asked to accept as closure.

By KOLUMN Magazine

The line at the check-cashing window is a kind of census. You see who is paid hourly. You see who doesn’t keep a bank account because a bank account, for them, has been less a tool than a trap—an overdraft fee as predictable as rent, a minimum balance requirement as fictional as retirement. In Flint, this line has lengthened and shortened over the last decade in ways that map directly onto the water crisis: the months when bottled water was another bill; the years when the state’s promises arrived as press conferences; the seasons when residents were told the water was “fine,” then told to flush their pipes, then told to wait for “the process.”

Now the process has a date attached to it.

In early December 2025, the court entered an order adopting the Special Master’s plan for how the Flint Water Crisis settlement money will be distributed. A few days later, public radio stations across Michigan began repeating the sentence that Flint residents have learned to treat like weather: Starting Friday, people with approved claims will be able to access an online payment portal to claim their money.

Online portal. Unique code. Award notice. Rolling basis. Thirty categories.

If you live in Flint, you have heard enough official vocabulary to last a lifetime. But the settlement is different—because it is supposed to be what a legal system calls “relief,” and what residents have often described as something closer to recognition. It is the closest thing to an admission that the harm was real. It is also, increasingly, another reason to ask what kind of recognition America offers a majority-Black city when the harm is undeniable and the accountability is negotiable.

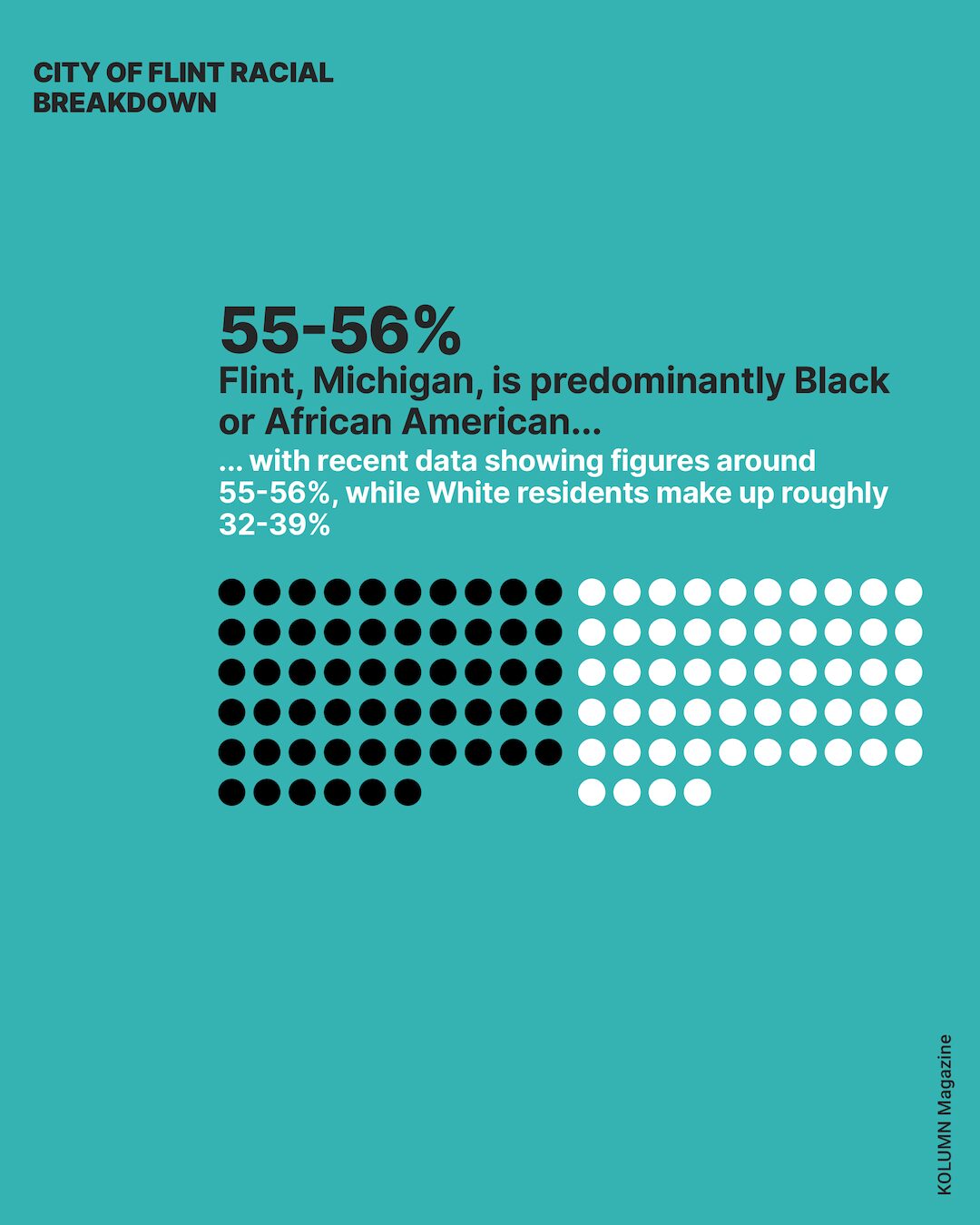

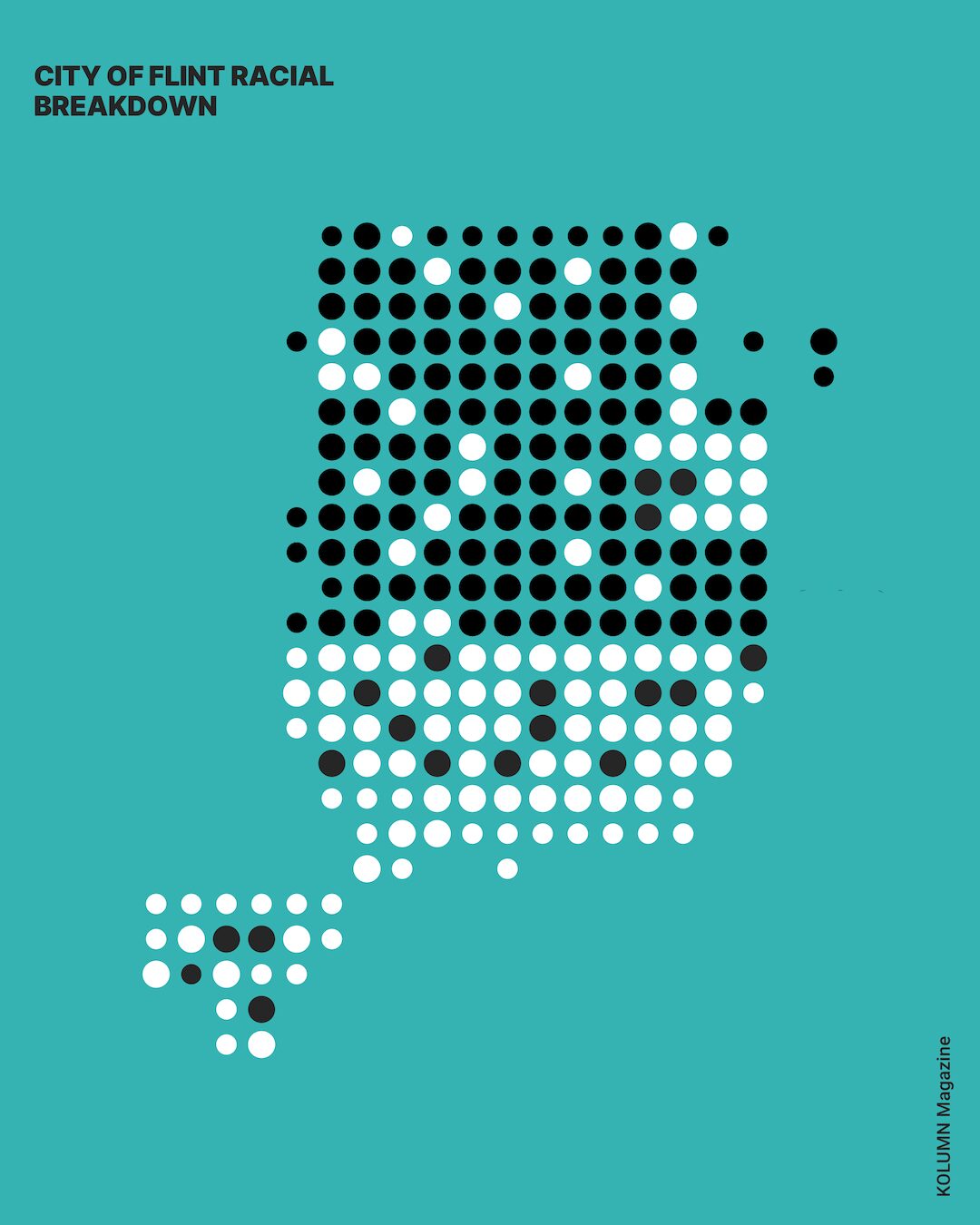

Flint is 56.7% Black, according to the U.S. Census Bureau’s QuickFacts for the city. The crisis—sparked by a decision to switch the city’s water source in 2014 and compounded by failures in corrosion control and oversight—became one of the most cited case studies of environmental injustice in modern American history. A decade on, it has also become something else: an extended lesson in how litigation can both validate trauma and repackage it into bureaucracy.

This story is about the Michigan water settlement—more precisely, the Flint Water Cases settlement fund and its current status—and why its mechanics matter as much as its headline number. It is about who gets paid, and who waits. It is about attorney fees, Medicare liens, and the quiet ways a settlement can punish people who never had the luxury of paperwork. And it is about how a Black community experiences “justice” when justice arrives through a portal login.

What the settlement is—and what it is not

The settlement at the center of Flint’s civil litigation is often described in shorthand as a “$626 million” or “over $600 million” fund. That shorthand is not wrong; it is incomplete.

In 2021, a federal judge approved a settlement of more than $600 million, with the bulk paid by the state of Michigan, described at the time as a milestone in the years-long battle over Flint’s contaminated water. Michigan’s Department of Health and Human Services summarizes the settlement’s final approval and the claims deadline (June 30, 2022), underscoring that this is a court-approved, time-limited claims process—not an open-ended reparations program.

The settlement fund itself, Michigan Public reports, has continued to grow from interest earnings since its initial creation, complicating even the basic question of “how big” the pot is.

But the critical point is not only the size. It is the structure.

As Michigan Public laid out in its December 9, 2025, reporting, the settlement is divided into 30 categories of claims. It allocates the bulk of the money to those who were minors during the crisis: 64.5% to children six and under at the time, 10% to children ages 7–11, 5% to ages 12–17, and 15% to adults with eligible injury. Property claims are allocated 3% (up to $1,000 per property), and business loss 0.5% (up to $5,000).

This allocation is both moral logic and actuarial logic: young children are understood as most vulnerable to lead’s effects, and the law—at least here—reflects that. It is also a reminder that the settlement is designed to distribute a finite sum among tens of thousands of people, which makes “justice” feel less like restoration and more like triage.

The Special Master overseeing the settlement, Deborah Greenspan, is a key figure in this phase—an administrator of consequence, tasked with turning injury into categories and categories into dollars. In late November 2025, she asked the court for permission to begin the distribution process, noting that awards would range broadly and that many payments would be lower than the public expects.

That is the settlement in theory. The question that Flint residents have been living inside is the settlement in time.

Why it took so long

If you want to understand the emotional temperature of Flint’s settlement era, start with a simple fact: for years, the people who seemed to be paid first were not residents.

In March 2024, Word In Black reported on the frustration that the settlement fund existed, but victims were still waiting while lawyers had already received money from the structure of the litigation. The Detroit Free Press similarly chronicled the delays and the sense among residents that time itself had become another injury.

This is not unique to Flint—class action settlements often move slowly, particularly when there are multiple defendants, complex categories, and large claimant pools. But Flint’s delay reads differently because the crisis itself was defined by institutional delay: officials dismissing residents’ concerns, data emerging slowly, accountability slipping.

The court process introduced new sources of delay. Among the most combustible has been the fight over attorney fees. Judges and lawyers describe fees as necessary to incentivize complex litigation; residents often experience fees as a second extraction—another entity taking its share from a pot meant to soothe harm.

In 2022, reporting based on an AP story noted that legal fees and expenses would come from the settlement pool, and that Michigan was paying $600 million while other parties covered the rest. Court documents themselves explicitly acknowledge the tension: every dollar awarded to attorneys is, by definition, a dollar less for claimants.

Bridge Michigan reported on estimates that lawyers could take around a quarter of the recovery, sparking objections and appeals that threatened further delays—an example of a familiar American paradox: the legal process that makes accountability possible can also postpone its effects.

In Flint, those postponements were not abstract. They were measured in prescriptions and in school years.

The Black impact: why Flint is not just “a city,” but a warning

To describe Flint as a place where something went wrong is to miss the point. Flint is a pattern.

Long before lead entered the water, Flint had been positioned—politically, economically, and racially—to absorb risk on behalf of others. The water crisis did not introduce inequality to the city; it exploited inequality that was already there, making visible what had long been normalized: that predominantly Black communities are more likely to be governed through austerity, experimentation, and delay, and then asked to endure the consequences quietly.

Flint is majority Black, and that fact is not incidental to the crisis or to its aftermath. It is central.

The decision to switch Flint’s water source in 2014 was made under emergency management, a governance structure imposed by the state that stripped local elected officials—many of them Black—of authority. Emergency management was framed as technocratic necessity, a neutral response to fiscal distress. In practice, it functioned as a suspension of democratic accountability in cities that were disproportionately Black. Flint was not the only city under emergency management, but it became the most infamous example of what happens when cost-saving logic outruns human consequence.

That is why Flint is a warning, not an outlier.

The water crisis followed a familiar script in Black America: residents noticed a problem, raised concerns, were dismissed, then blamed for their own suffering. Officials assured them the water was safe. Data was invoked as a shield. When rashes appeared, when hair fell out, when children’s blood lead levels rose, the burden of proof remained on the residents. They were asked, implicitly and explicitly, to demonstrate harm that the state had an obligation to prevent.

This dynamic—of disbelief first, accountability later—has deep roots. From industrial pollution corridors in Louisiana to contaminated soil in Chicago, environmental harm in Black communities has often been treated as unfortunate but tolerable, the price of economic efficiency or bureaucratic convenience. Flint forced the country to watch that logic play out in real time.

The settlement, then, is not simply about compensating individuals. It is about what the legal system does when confronted with a harm that is both collective and racialized.

The categories of compensation—property damage, bodily injury, childhood exposure—attempt to individualize what was, in reality, a communal trauma. This is a necessary function of litigation, but it carries risk. When harm is individualized, the structural forces that produced it can recede into the background. The question shifts from Why did this happen to a Black city? to How much is this person owed?

For Black Flint residents, that shift can feel like erasure by spreadsheet.

Lead exposure does not land on a blank slate. Its effects are shaped by housing quality, access to healthcare, school resources, and neighborhood stability—conditions that are themselves the result of decades of racialized policy. A child exposed to lead in a well-resourced suburb encounters a different set of buffers than a child exposed in a city already contending with underfunded schools and limited healthcare access. The toxin may be the same; the outcome is not.

This is why researchers and advocates have consistently emphasized that the Flint crisis cannot be understood apart from race. Studies have shown that Black babies in Flint experienced worsened birth outcomes after the water switch. Community reporting has underscored how poverty amplifies the long-term effects of toxic exposure. These findings do not suggest that lead “targets” Black people biologically; they demonstrate how social vulnerability determines whose exposure becomes destiny.

The settlement acknowledges this reality indirectly—by allocating the largest share of funds to children who were youngest during the crisis—but it does not name it. Race does not appear as a category. Environmental racism is not a line item. The law compensates outcomes, not structures.

That omission matters because Flint is being watched.

Communities across the country—many of them Black, many of them poor—are grappling with aging infrastructure, unaffordable water bills, and regulatory neglect. Jackson, Mississippi. Baltimore, Maryland. Newark, New Jersey. Each has faced water-related crises with echoes of Flint’s story: warnings ignored, residents blamed, repairs delayed, trust eroded.

What Flint teaches these communities is not only that harm can be proven, but that proof takes years—and that even when the state is forced to pay, the payment comes with conditions, categories, and ceilings.

There is also a political warning embedded in Flint’s aftermath. The same state that agreed to a historic settlement has, in other contexts, moved to declare the crisis “over,” citing regulatory milestones as justification for withdrawing targeted support. This tension—between legal acknowledgment and political fatigue—is one Black communities recognize. Attention arrives during crisis; resources retreat during recovery.

For Flint residents, the settlement is therefore double-edged. It validates what they have said all along: the harm was real, measurable, compensable. But it also risks becoming a punctuation mark, used by outsiders to conclude a story that residents are still living.

In Black communities, closure is often imposed rather than earned.

The deeper warning Flint offers is about governance. When democratic power is removed, when communities are managed rather than represented, when fiscal efficiency is prioritized over lived experience, harm becomes more likely—and accountability more elusive. Emergency management made Flint vulnerable. The settlement does not undo that vulnerability; it compensates for one of its consequences.

And then there is the matter of memory.

Flint’s children are growing up with a civic education few textbooks offer. They learned that official assurances can be wrong. That expertise can be weaponized against the vulnerable. That justice, when it comes, is slow and partial. They learned that their city became a national symbol—and that symbols can be abandoned once they stop being useful.

This is why Flint is not just a city. It is a case study in how race, governance, and environmental risk intersect in America. It is a warning about what happens when Black communities are treated as testing grounds for austerity and patience. And it is a measure of how much the country is willing to pay—financially and morally—when that treatment finally becomes undeniable.

The settlement answers one question: Did the harm matter?

The harder question remains unresolved: What will be done differently next time—and in which city?

The lawsuit’s current state: what changed in December 2025

For years, “the settlement” in Flint functioned like a rumor with paperwork: residents knew it existed, and many had filed claims, but few had concrete movement.

That changed in early December 2025.

The official court-authorized settlement website—the one that residents are instructed to trust—states that on November 21, 2025, the Special Master issued a detailed Report and Recommendation requesting court approval to distribute settlement money, and that on December 5, 2025, the court entered an order adopting that recommendation. The same site explains that the order authorizes distribution on a rolling basis, beginning with a first set of approved residential property damage claims meeting specific criteria.

Michigan Public’s December 5 reporting adds critical texture: the order provides direction on remaining issues, including approximately 1,100 Medicare-entitled claimants whose awards are subject to Medicare liens, and the unresolved question of attorney fees. It also notes that the Special Master must still complete final calculations to determine exact payouts across the 30 categories.

Then, on December 9, 2025, Michigan Public reported that letters would begin arriving, each containing a unique code to access the online payment portal, with the “starting Friday” language indicating that the portal access for approved claimants would begin on Friday, December 12, 2025.

In other words: the settlement has entered its distribution era. But “distribution” is not synonymous with “resolution.”

The hidden inequality inside “how will you receive your payment?”

On the settlement website, the question appears almost as an afterthought, tucked among FAQs about passwords and timelines:

What if I don’t have a bank account and can’t use an electronic transfer?

It is a practical question, phrased politely, as if it were about preference rather than access. But in Flint—where the water crisis hollowed out trust not only in government but in institutions broadly—it is one of the most revealing questions in the entire settlement process. It exposes a quiet truth about how justice is delivered in America: even when compensation is finally authorized, it still assumes a certain kind of citizen.

To receive settlement funds “efficiently,” claimants are encouraged to use direct deposit or electronic payment systems. The language is standard, borrowed from payroll departments and class-action settlements across the country. It presumes stable internet access, a reliable email address, and—most critically—a bank account that can accept and hold funds without penalty.

But Flint is not a city where those assumptions hold evenly.

According to Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation data, Black households nationwide are more than twice as likely as white households to be unbanked or underbanked. In cities like Flint—where decades of deindustrialization, emergency management, and municipal austerity have eroded household stability—that gap is not theoretical. It shows up in the lived strategies people use to survive: prepaid debit cards with hidden fees, check-cashing storefronts that take a percentage off the top, informal cash economies built not out of preference but necessity.

For many Flint residents, a bank account has not been a neutral tool. It has been a site of extraction.

Overdraft fees triggered by a single miscalculation. Minimum balance requirements that punish poverty. Accounts closed after cascading penalties, leaving behind negative balances that make reopening impossible without upfront cash. For residents already paying extra to avoid contaminated water—buying bottled water, filters, replacement fixtures—the banking system often felt like another place where being poor cost more.

So when the settlement portal asks how claimants would like to receive their money, it is not offering equal choices. It is asking residents to navigate a financial infrastructure that has repeatedly failed them.

Consider the resident who has an account but keeps it intentionally empty, using it only when absolutely necessary, because a single unexpected debit can trigger fees they cannot absorb. A settlement payment deposited electronically may vanish almost immediately—absorbed by past-due utilities, auto-debited bills, or negative balances from years prior. The money arrives and disappears, leaving behind the familiar sensation that relief passed through without stopping.

Or consider the resident without an account, who opts for a paper check. That check must be cashed somewhere, often at a storefront that takes 2 to 10 percent in fees. For a $1,000 property claim, that can mean losing $50 to $100 instantly—money the settlement never intended to give to anyone but the claimant. Justice, in this case, leaks.

There is also the matter of timing. Electronic transfers are faster; checks are slower. Slower processing means longer exposure to uncertainty—whether the check will arrive, whether it will clear, whether it will be lost or stolen. For people whose lives have already been structured around waiting—waiting for clean water, waiting for answers, waiting for accountability—the method of payment becomes another clock ticking unevenly.

The settlement administrators have attempted to anticipate these realities, offering alternatives and customer service lines. But mitigation is not the same as design. The system was not built around the most vulnerable claimants; it was adapted to them after the fact.

This gap between design and reality mirrors the original crisis. Flint’s water switch was engineered on paper, justified through spreadsheets and cost-saving logic that failed to account for how people actually lived. The settlement, too, is engineered for efficiency, not equity. It moves money—but through channels that reward those already integrated into mainstream financial systems.

For Black Flint residents, this is not incidental. The same structural forces that made the water crisis possible—racial segregation, political disempowerment, economic precarity—also shape who can access settlement funds cleanly and who pays a toll. Environmental injustice does not end at exposure; it extends into remediation.

There is a deeper psychological layer as well. To accept electronic payment, residents are asked to trust again: to enter personal information into a portal, to believe that the system will not misfire, to assume that errors can be corrected. For a community that learned, painfully, that official assurances about safety were false, that trust is not automatic. Skepticism is rational.

Some residents have described treating the settlement portal the way they treated the tap during the crisis years: cautiously, with verification, with backups. Screenshots saved. Calls logged. Paper copies printed. The behavior is not paranoia; it is adaptation.

In this sense, the question “how will you receive your payment?” is not administrative. It is diagnostic. It reveals how deeply inequality is embedded even in moments meant to signal repair. It shows how a legal victory can still ask more of those who already gave the most: more paperwork, more patience, more risk.

The settlement money will arrive. That is no longer in serious doubt. What remains uncertain is how much of it will survive the journey intact—and what it means when justice, once finally authorized, still has to pass through systems that quietly skim, delay, and erode.

In Flint, the water taught residents that contamination is not always visible. The settlement is teaching a parallel lesson: neither is inequality.

The property claims: why $1,000 is both money and message

The first distribution phase is expected to involve property claims. Michigan Public reported there are approximately 7,000 approved property claims worth about $1,000 each.

A thousand dollars can matter. It can also feel like an insult, depending on what you believe you lost.

Property claims are, by design, capped and narrow. They attempt to quantify a category of harm that was widespread but not easily documented: damage to plumbing, fixtures, and the value of a home in a city where many homes are already undervalued. The cap can feel like a declaration that property damage is the simplest harm—when, in reality, property damage in Flint also meant time, fear, and the psychological cost of living in a house whose water might poison your child.

In Flint, the settlement’s property-first distribution carries symbolic weight: it tells residents that the first checks will arrive for what can be categorized most easily, not necessarily for what hurt most deeply.

The children’s claims: valuing childhood without pretending money is enough

Some claims—particularly those involving people who were young children during the crisis with documented high lead exposure—may receive compensation around $100,000.

That number has become a kind of headline inside Flint: the figure people repeat when asked whether the settlement is “real.” It is also a number that, in practice, will apply to a subset—those whose documentation aligns with the settlement’s categories and proof requirements.

This is one reason residents and advocates have warned for years that expectations could become a second injury: the public imagines windfalls; the settlement, built to divide finite funds among many, delivers something closer to “modest,” in the Special Master’s own phrasing.

And the deeper question remains: what does it mean to price a childhood?

Lead exposure can have lifelong impacts. Even where outcomes are not catastrophic, they can be diffuse: difficulties focusing, behavioral challenges, learning delays. These are the kinds of harms that do not arrive as a single hospital bill but as years of extra support, extra stress, and sometimes extra shame.

In Black communities, those harms are often compounded by under-resourced schools and health systems—meaning that the same lead exposure can produce different life trajectories depending on the availability of support. That is why studies emphasizing the disproportionate impacts on Black babies—and reporting emphasizing how poverty amplifies toxic exposure—matter in this context.

A settlement check cannot replace the support systems that should have been robust long before 2014. It can, at best, fund a fragment of what was lost. The risk is that outsiders will treat the check as closure.

The unresolved fights: liens, fees, and the politics of “the end”

The court’s December 2025 order did not end every dispute. It authorized a process.

Michigan Public’s reporting noted key outstanding issues: Medicare liens for roughly 1,100 Medicare-entitled claimants and the continuing issue of attorneys’ fees. These issues sound technical. They can be life-altering.

A Medicare lien means that if medical expenses were paid by Medicare, the government may seek reimbursement from settlement proceeds. For residents whose health has been strained, this can feel like yet another entity standing between them and relief—another reminder that “compensation” is never fully theirs.

Attorney fees remain politically explosive for reasons that go beyond dollar amounts. They symbolize whose labor the legal system values most—and whose suffering it values least. Word In Black’s reporting in 2024 captured the anger that lawyers appeared to be the only ones paid while victims waited. Earlier reporting and court documents show that fee awards and disputes were central to delays and to residents’ distrust of the process.

All of this unfolds against a broader political backdrop in Michigan: elected officials and institutions eager to declare chapters closed. In July 2025, The Washington Post reported that Flint had completed replacement of nearly 11,000 lead pipes, framing it as a milestone “bringing one of the nation’s most devastating environmental crises to an end,” while also noting the national scope of lead infrastructure and the federal push to replace lead pipes.

Milestones are real. But Flint residents have learned that milestones can be used as rhetorical exits. The settlement, too, can be used that way: as an argument that the state has “paid” and can therefore move on.

A Black city, a national template

The Flint settlement has become a template other communities watch—Jackson, Baltimore, Cleveland—places where water, race, and governance collide.

Civil rights organizations have framed water as a civil rights issue, arguing that discrimination and municipal divestment have long shaped who gets safe, affordable water. Flint’s story sits squarely inside that lineage: a city made vulnerable by policy, then asked to prove it was harmed.

Ebony’s reporting on Flint’s lead pipe replacement milestone in 2025 underscores that even apparent infrastructure “completion” comes with concerns and community skepticism—another sign that “fixing” is not the same as healing. The Guardian’s ten-year retrospective captured the ongoing trauma, the distrust, and the sense that the crisis remains an open wound.

And that is the key investigative point: Flint’s crisis did not end when the water chemistry stabilized. It did not end when a settlement was approved. It does not end when a portal opens.

The lawsuit’s current state—December 2025 orders, rolling distributions, unresolved fees and liens—tells us what the American system does when it finally admits harm: it builds a machine to process that harm. The machine has rules. The rules have deadlines. The rules assume technology, documentation, and, often, trust.

Flint has never had much reason to trust the machine.

What residents are left to decide

In the months ahead, Flint families will make choices that look small but are not.

Whether to select electronic transfer or a check. Whether to use a bank account that has punished them before. Whether to believe the award notice is accurate. Whether to tell their children that the settlement is “justice,” or simply a check from a system that moved too slowly to deserve the word.

For Black Flint residents, those choices sit inside a national narrative in which Black suffering is often treated as inevitable—until it becomes embarrassing, and then it becomes procedural. The settlement is, in one reading, a victory: proof that residents fought, filed, and forced the state to pay. In another reading, it is an indictment: proof that residents had to litigate for what should have been protected by regulation and conscience.

The line at the check-cashing window will not be empty. The bank lobbies will not suddenly fill. Flint’s trust will not be restored by a Friday portal opening.

But the checks will begin to arrive.

And when they do, Flint will confront a question that is both intimate and political: What do you do with money that arrives as apology, but feels like proof that you were right to doubt the people who told you to drink the water?