KOLUMN Magazine

Before Ring, There Was Brown

The forgotten Black couple whose 1969 patent anticipated the entire smart-home revolution.

By KOLUMN Magazine

On a winter evening in Queens in the late 1960s, before anyone could imagine a video doorbell on every stoop, Marie Van Brittan Brown sat at home and listened.

She listened for footsteps in the hallway of her South Jamaica building, for the jangle of keys that meant her husband, Albert, was finally back from another late shift as an electronics technician. More often, she listened for sounds she did not want to hear: raised voices, a fist slamming against a neighbor’s door, the crack of something breaking somewhere just beyond the thin apartment walls.

Queens was changing. Serious crime had surged by more than 30 percent in the first half of the decade and calls to police could mean long minutes of silence before a squad car appeared, if it appeared at all. Marie worked nights as a nurse. Albert worked odd hours, too. Their schedules meant that she was frequently home alone with their young children, rehearsing in her mind what she would do if someone forced their way in.

She did not organize a press conference or lobby City Hall. Instead, in the cramped living room of a modest house just off 135th Avenue, Marie and Albert started sketching a system that would allow her to see danger before it stepped through the door.

They were, without quite knowing it, drawing the blueprint for the modern home security industry.

The Woman Behind the Monitor

The public record is surprisingly thin for a figure whose ideas now sit in millions of doorways.

Marie Van Brittan Brown was born in New York City in the early 1920s. Her parents, Theodore Felton and Lillian Robinson, came from families who migrated north from the Carolinas and Pennsylvania, part of a wave of Black Americans reshaping the urban Northeast. She grew up in a city that promised opportunity but offered little protection, especially in Black neighborhoods often isolated by discriminatory housing policies and uneven policing.

By the time she married Albert L. Brown, an electronics technician, in 1949, she had trained as a nurse—a job that demanded long, irregular hours. The couple settled in Jamaica, Queens, where they raised their children across from what would become John F. Kennedy International Airport.

Crime was rising. Police response times were inconsistent. Night shifts meant Marie was often alone. Her fear became the foundation for invention.

Turning a Front Door Into a Control Center

The Design Problem No One Else Was Solving

Home security, as a concept, barely existed in the 1960s. Banks had CCTV. Government facilities had guarded entry points. Some corporations used rudimentary surveillance technologies. But the idea that a private home—especially a modest, working-class home—should be outfitted with a real-time visual monitoring system was almost unthinkable.

Residential safety had been gendered and racialized into a set of assumptions:

• that men protected their households

• that women were protected

• and that Black families, particularly in urban neighborhoods, were simply left out of the conversation entirely.

Marie, by contrast, understood that the home was not automatically safe—and that those who felt fear most acutely were often those least served by the existing system.

Her lived experience became her technical brief.

The Engineering: A System Decades Ahead of Its Time

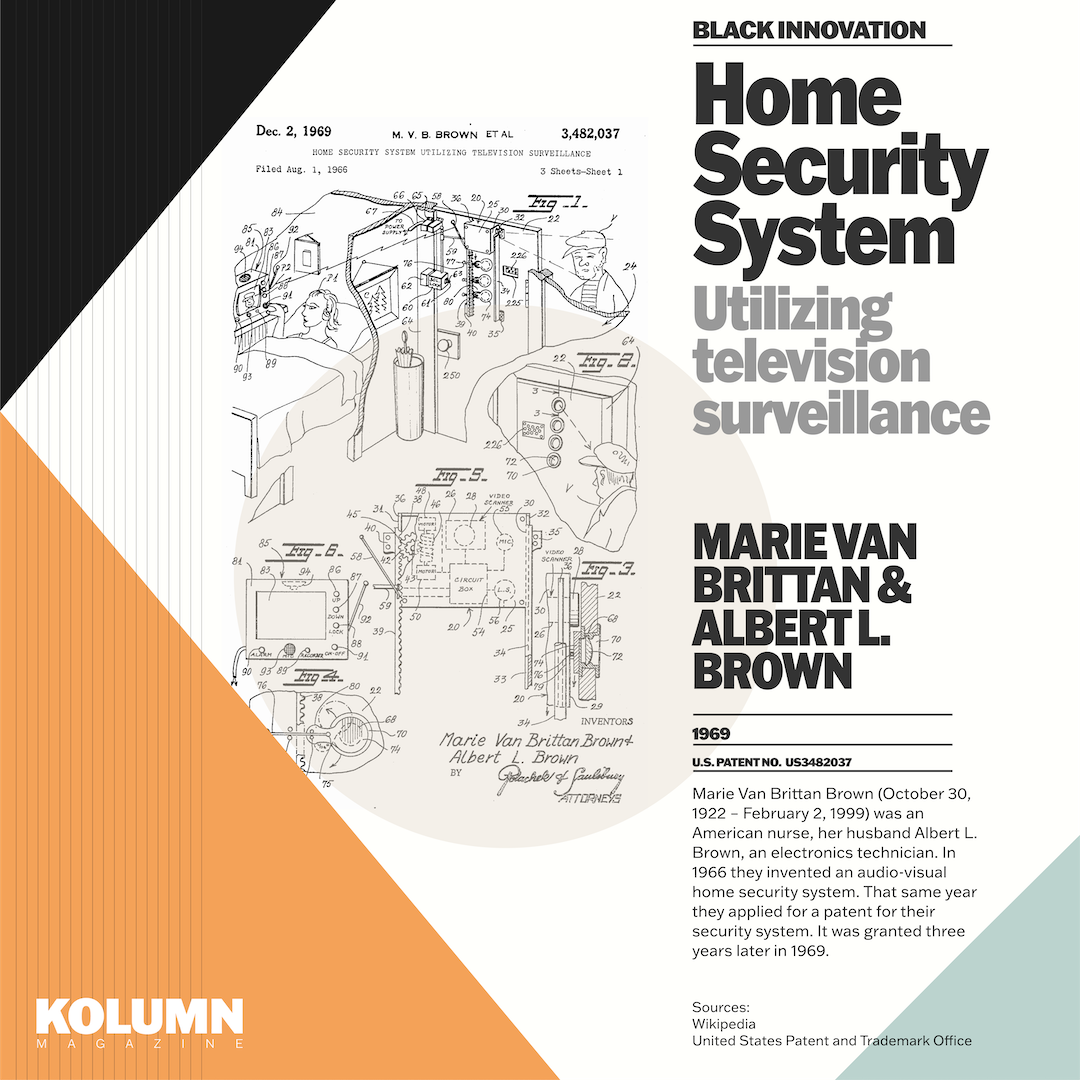

Their early sketches—which would become Patent No. 3,482,037—show a transformation of the front door from passive threshold to operational hub.

The Browns’ system began with a row of four vertically aligned peepholes. Rather than assuming a single eye level, Marie insisted on varying heights: one for a child, one for an average adult, one for someone tall, and one low enough to capture a crouched or concealed visitor. A camera affixed to a vertical track on the interior side of the door moved mechanically to align with each peephole. That camera transmitted its image to a monitor located elsewhere in the home, allowing the resident to evaluate the visitor from a secure, hidden vantage point.

The system incorporated:

A two-way audio system

A microphone outside and a speaker inside allowed the resident to communicate without approaching the door. This was decades before commercial intercom systems became commonplace.

A remote-controlled door latch

Using electrical wiring and a simple actuator, the Browns enabled the resident to unlock the door from a separate room—an early version of “remote access,” now a pillar of smart-home design.

A built-in alarm system

A single switch activated a radio signal to summon help, presaging the panic buttons now standard in-home security packages.

It was a convergence of optics, audio engineering, remote actuation, and emergency broadcasting—an integrated system so far ahead of its time that no existing company had a market category for it.

The Domestic Laboratory

Neighbors recalled seeing wires strewn across the Browns’ living room floor, tools laid out beside children’s toys, and Albert adjusting circuits while Marie timed her walk from the door to the bedroom monitor. Their home became a hybrid space—a site of caregiving, child-rearing, and innovation.

Marie ensured the system functioned under stress:

• She practiced pressing the alarm as if jolted awake.

• She simulated approaching footsteps and unexpected knocks.

• She insisted the controls be intuitive enough for a frightened child or a panicked adult.

Her design sensibility was rooted in lived reality, not theory. Albert later said that his role was to “make the technology do what Marie already knew it needed to do.”

A Radical Reimagining of Domestic Power

In its essence, the Browns’ invention transferred the moment of confrontation—from the threshold to a place of safety deeper within the home. It was a redistribution of power along lines unacknowledged in 1960s America: empowering Black women, empowering night-shift workers, empowering anyone who had learned to fear the knock at the door.

The system challenged assumptions embedded in mid-century domestic life:

• that women were passive recipients of security

• that innovation flowed only from institutions

• that working-class homes were sites of consumption, not invention

Marie’s system was a rebuttal to each assumption—and a precursor to the surveillance culture that would come to define the twenty-first century.

The Commercial Market Wasn’t Ready—but the Future Was

Had manufacturers adopted the Browns’ invention in 1969, it may have arrived before society was prepared to understand it. Instead, the system remained a brilliant prototype. But over the next several decades, its conceptual DNA resurfaced everywhere: in doorbell cameras, intercoms, keyless entry systems, and smart-home platforms.

Their front door became a control center. Modern American domestic life has been catching up ever since.

A Brief Flicker of Recognition

The Browns received their patent on December 2, 1969, and a small article in the New York Times soon followed. Reporters described the device as an “audio-video alarm,” an innovation that might protect not just homeowners but doctors, office workers, and anyone operating in unpredictable environments. Manufacturers were intrigued but saw no clear market. Residential security was not yet a consumer category, and the hardware costs were prohibitive.

Marie was honored by at least one national scientific organization. But the press moved on, and without corporate backing, the invention fell into a quiet obscurity.

Ahead of the Industry They Helped Create

Decades passed before the Browns’ influence resurfaced. Patent examiners, engineers, and academic researchers began to cite their design when discussing home surveillance systems. The features Marie and Albert pioneered—remote viewing, two-way audio, controlled entry, and emergency signaling—became foundational elements of smart-home architecture.

Today’s doorbell cameras echo the Browns’ vision more directly than most consumers realize.

Race, Gender, and a Vanishing Inventor

Marie’s historical invisibility reflects broader patterns in American innovation. Black inventors—particularly Black women—have routinely seen their contributions minimized or lost. She did not work in an R&D lab. She had no corporate patron. Her expertise emerged from necessity, not formal training.

Institutions rewarded ideas born in laboratories, not living rooms.

But as historical scholarship expanded, her work began to reappear in cultural and academic narratives. Smithsonian Magazine, the Lemelson-MIT Program, and multiple STEM-focused organizations now highlight Marie as a foundational figure in residential security technology.

Crucially, her story has been amplified by KOLUMN Magazine’s “Black Innovators & Inventors” series, which profiles overlooked Black creators whose work shaped American life. In this digital archive, Marie is not an obscure figure but part of a lineage of intellectual and technical creativity that spans generations.

From Queens to the Cloud

Modern home-security systems—Ring, Nest, SimpliSafe, Vivint—are not direct descendants in a patent sense, but their architecture is unmistakably aligned with the principles the Browns laid down. A homeowner now checks a live feed from across the world, speaks through a doorbell speaker, unlocks a door remotely, or triggers an alarm—all concepts Marie mapped meticulously on paper in 1966.

But ubiquity brings tension. These devices raise new questions about privacy, policing, surveillance norms, and the unintended consequences of constant monitoring.

Marie wanted empowerment, not omnipresence. She sought protection, not digital vigilance over entire neighborhoods.

Yet her invention seeded a revolution whose reach extends far beyond what she could have imagined.

The Browns’ Quiet Legacy

Marie died in Queens in 1999. Albert had passed earlier. Their daughter Norma, who became a nurse and held a patent of her own, carried forward the family’s inventive spirit.

The Browns did not live to see their system’s conceptual triumph. But their innovation reshaped expectations about what it means to feel safe at home.

She began with fear and frustration. She ended by altering the architecture of domestic life.

Her front door became a control center. The world followed.