No products in the cart.

KOLUMN Magazine

Inside a

Phila. House

Where

Black Girlhood

Is the Main

Exhibit

In Germantown, The Colored Girls Museum turns an ordinary Victorian home—and the everyday objects of Black women’s lives—into a living archive of care, grief and joy.

By KOLUMN Magazine

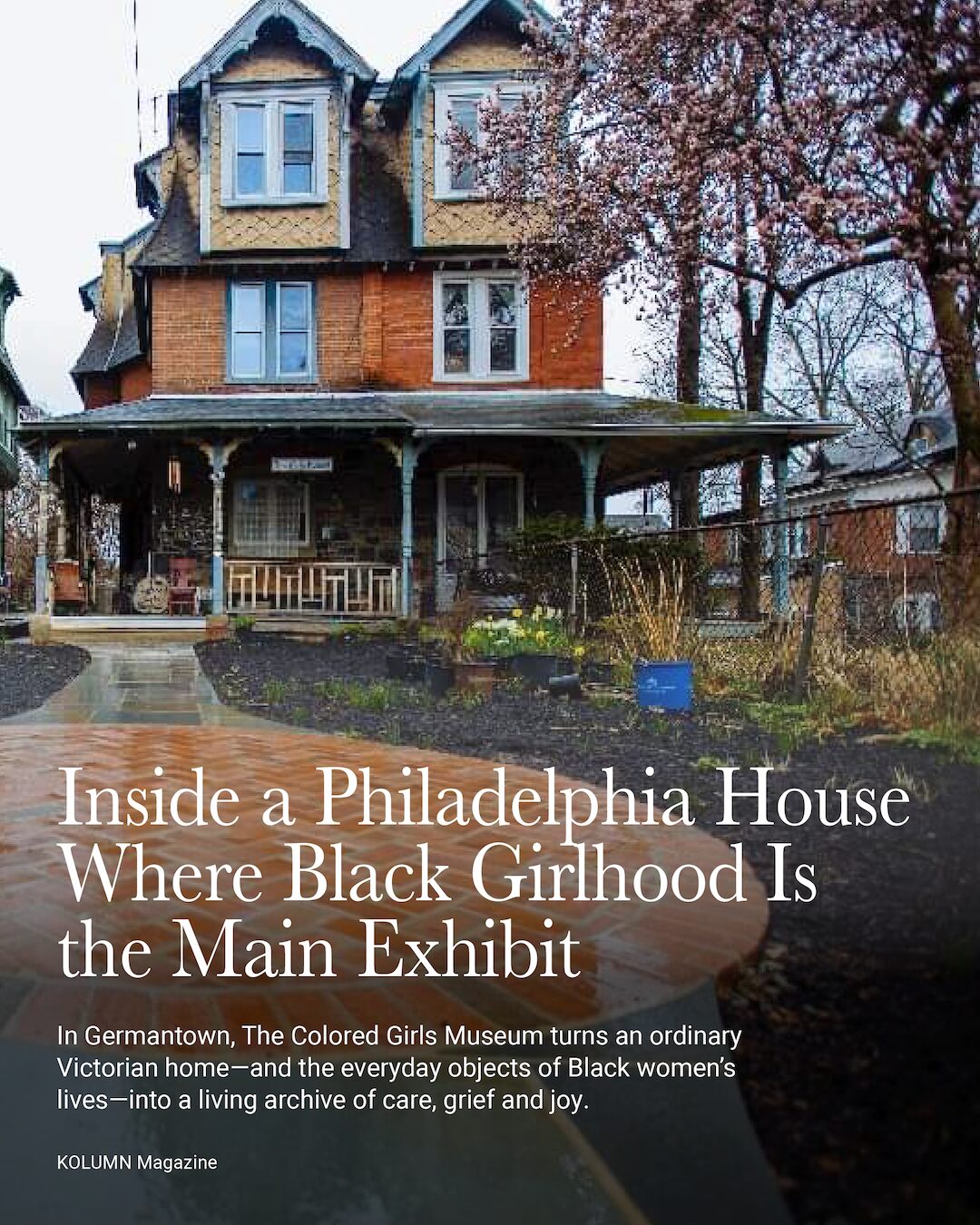

On a narrow Germantown block in Northwest Philadelphia, the museum doesn’t look like a museum at all. It’s a three-story Victorian twin—stone façade, modest porch, the kind of house you’d expect to hold a big family, not an institution. The hand-painted sign above the door reads “The Colored Girls Museum,” but the more important message comes from the threshold itself: a black art-deco iron gate, a short walkway lined with sculptures and potted plants, a front door often held open as if the house has been waiting all day just for you.

Inside, the air is thick with the layered smells of old wood, shea butter, incense, maybe someone’s hair oil. Walls bloom with portraits of Black girls and women—some smiling directly at you, others rendered in celestial blues or hot pinks, all of them insisting on a kind of looking that is not casual but deliberate. The sofas are not roped off. The lamps are lit. A corner table might be an altar, or it might be somebody’s grandmother’s dresser, now holding a constellation of family photos.

“Sometimes you just have to do the thing with what you have,” founder and executive director Vashti DuBois has said of this house-turned-museum. What she had, in 2015, was a 135-year-old home in Germantown, the fresh grief of her husband’s death, and three decades of work in organizations that promised to center women and girls of color but rarely did in the way she imagined. Out of those materials she built something new: a museum that calls itself a “memoir museum” and asks one audacious question—what if the ordinary Black girl were treated as history’s central figure rather than its footnote?

A house that became a thesis

DuBois is not a curator by traditional training; she’s a social practice artist and nonprofit veteran who studied theater at Wesleyan University and spent years working in organizations focused on the educational and economic needs of Black women and girls.

By 2014, she had returned to Philadelphia and to the Germantown house she shared with her husband and children. When her husband died suddenly that year, the house became a vessel for grief—and, eventually, a thesis. In interviews, DuBois has described wanting “someplace that I could put my grief that wasn’t painful and that could be lovely,” a space where mourning could coexist with reverence for the lives of Black women and girls.

She began to experiment: inviting artists to install work in her living room, letting friends leave objects that meant something to them—hair combs, church hats, school trophies, an auntie’s perfume bottle. Slowly, the house started to articulate a new kind of institution: not a mausoleum for famous names, but a living museum where the exhibits might be a thrift-store dress or a handwritten recipe, as long as a “Colored Girl” said, This is a piece of my story.

By September 2015, those experiments had hardened into an institution with a name: The Colored Girls Museum. Envisioned and founded by DuBois, the museum was conceived as “a multidisciplinary memoir museum focused on the ordinary colored girl,” sustained not by a major endowment but by a collective of artists, neighbors, friends, educators and students.

There was one guiding principle: the house itself would not be neutral. “She loves to perform and play dress-up. She’s really an entertainer at heart,” DuBois has joked about the building, treating it as a protagonist rather than a container. Every room, every staircase, every alcove could be staged to evoke some facet of Black girlhood, from bedrooms that look like sanctuaries to kitchens that double as shrines to survival.

A museum of objects, not relics

On paper, The Colored Girls Museum’s mission is straightforward: to honor the stories, experiences and history of ordinary “Colored Girls”—a term DuBois uses deliberately, in homage to Ntozake Shange and to the generations of Black women and girls who lived under that descriptor.

In practice, the museum operates by a quiet but radical logic. Rather than beginning with a theme and then acquiring objects, it starts with the objects themselves. A “Colored Girl” submits something from her life—a prom dress, a bus pass, a battered copy of Beloved—along with the story of why that object matters. The museum then “initiates the object” into the collection as a representative of her personal history.

These are not relics rescued from some grand historical archive; they’re the kinds of things that usually languish in attics or are quietly thrown away when someone dies. In DuBois’s hands, they become evidence: proof that a life was lived, that a girl existed in the world with desires and disappointments and small, incandescent moments of joy.

A plastic hair barrette becomes an artifact of mornings at the kitchen table, a mother’s fingers moving quickly through a child’s hair before school. A chipped coffee mug stands in for the long, unglamorous labor of caretaking that rarely makes it into official histories. None of these objects would impress a traditional acquisitions committee. That’s the point.

“The first of its kind,” the museum’s own description notes, “the museum initiates the object—submitted by the Colored Girl herself—as a representative of an aspect of her story and personal history which she finds meaningful.”

The founders’ circle

Although DuBois is the public face and conceptual architect, The Colored Girls Museum was never a solo project. As the idea solidified, she was joined by a small circle of collaborators who helped translate vision into practice.

Michael Clemmons, a visual artist and director of Temple University’s Center for Community Partnerships, became the museum’s curator. Since its opening in 2015, he has helped steer the design and implementation of at least eleven exhibitions, many of them sprawling, whole-house experiences that ask visitors not just to look at art but to move through it.

Another early collaborator, curator and DJ Ian Friday, worked with DuBois as she formally converted the house into a museum in 2015, shaping its soundscape and conceptual frames. Together, they imagined a place where the museum could be as much about ritual as about display—where music, scent, and touch mattered as much as captions on the wall.

From the beginning, the founding team understood that this would not be a white-cube institution. There would be no vast lobby, no café run by a celebrity chef. There would be a porch, where neighbors might stop by with a question or a casserole; there would be a kitchen table where planning meetings bled into potlucks; there would be a constant negotiation between the needs of a home and the demands of a museum.

The institution that emerged is “established and supported by a diverse collective of community members,” as one profile put it, with artists, neighbors, educators, and students sharing ownership over the museum’s direction and day-to-day life.

Exhibitions that ask you to sit, listen, stay

If large museums often pride themselves on encyclopedic collections, The Colored Girls Museum tends to think more in seasons—a series of exhibitions that unfold like chapters in an ongoing memoir. Visitors who return every year find that the house is never quite the same.

One exhibition, “Sit a Spell,” invited guests to literally take a seat—on sofas, at kitchen tables, in corners that felt like living rooms recreated from memory—and linger with portraits of Black girls and women. College students who toured the show with their diversity office described the museum as unlike any place they had ever been; the work seemed to rearrange their sense of what counts as art and whose stories deserve a spotlight.

Another series, “The One Room Schoolhouse,” transformed parts of the museum into a reimagined classroom—a space to consider how Black girls have historically been disciplined, misread, or underestimated in educational settings, but also how they have built their own intellectual communities.

Most recently, a workshop production called The Intermission has turned the house fully into theater. The exhibition casts the 140-year-old home as a protagonist, along with a widow and an ordinary Colored Girl, all navigating intersecting realities in a quest to find their way back home—or back to one another. Audiences are not simply spectators; they are, in effect, extras in a living play about grief, love, and return.

Even when the shows change, the through-line remains: Black girlhood as sacred, ordinary Black women’s lives as museum-worthy. “The Colored Girls Museum serves as a cherished community space that celebrates the extraordinary lives of often-overlooked ‘colored girls’ through evocative art and significant artifacts,” one recent exhibition partner wrote.

A neighborhood institution, not a destination alone

Germantown is not a neighborhood typically mapped onto Philadelphia’s mainstream museum circuit. Tourists who come for art are often directed toward the Benjamin Franklin Parkway, where the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Barnes Foundation and the Rodin Museum cluster like a cultural archipelago.

The Colored Girls Museum exists in a different ecosystem—one defined by corner stores, rowhouses, and a network of small but storied institutions like Historic Germantown, of which the museum is now a member site. The partnership means that visitors following a heritage trail can find their way to DuBois’s front steps as easily as to old colonial houses.

On neighborhood Facebook pages and in local guides, the museum is sometimes described as “the flyyest art space” on the Philadelphia Open Studio Tours route, a place visitors are urged not to miss. That language matters; it marks the museum not as an anomaly but as a local treasure, woven into Germantown’s identity as a historically Black, fiercely independent neighborhood.

Community engagement here doesn’t just mean children’s workshops or an annual fundraising gala—though there are both. It means being the house that’s always open for a talk, the space where Black girls see themselves on the walls, the institution that accepts an object from a neighbor and says, Yes, this matters enough to be in a museum.

Teaching the world to “sight” Black girlhood

Over time, the museum’s reach has stretched well beyond Germantown. One of its most ambitious collaborations is Sighting Black Girlhood, a University of Pennsylvania course built in partnership with The Colored Girls Museum and its Mobile Museum Project, “The First Time Ever I Saw Your Face.”

The course uses the museum’s philosophy as curriculum: students engage with scholarship and storytelling that treat Black girlhood not as a problem to be solved but as a sacred space. They study the museum’s 2020 portrait campaign, which invited Black girls and women to be photographed and presented as monuments to their own lives, each image a ritual of care.

In classrooms and on the road, the Mobile Museum carries that ethos into schools, community centers, and festivals, setting up temporary exhibits where Black girls are invited to see themselves differently. It is one thing to bring a group of students to Germantown; it is another to bring the museum to them, to stake a claim that their own everyday spaces are worthy of art and reverence.

This kind of work has made the museum something of a quiet export. Philadelphia arts organizations describe it as a “cherished community space” whose exhibitions illuminate themes that reach far beyond one city. In 2020, DuBois was named a “Philadelphia Culture Treasure” for “providing agency and visibility for the practices and histories of artists often excluded from the canon.”

Ordinary extraordinary: who gets a museum?

The existence of The Colored Girls Museum raises a simple but disruptive question: Who, exactly, is museum-worthy?

Traditional museums tend to answer with a familiar list—presidents, generals, avant-garde artists whose works sell for eight figures at auction. Even as institutions race to diversify their collections and boards, the architecture of prestige often remains the same: big names, big donors, big buildings.

DuBois’s house insists on a different equation. Here, the protagonists are women and girls who might otherwise never see their faces on a museum wall. The museum’s own language is explicit about this: it honors the “ordinary extraordinary colored girl,” treating her story as both singular and representative of something larger.

That framing is not just sentiment; it is a critique. When a chipped teacup or a well-worn church hat is initiated into the museum’s collection, it enters the same conceptual category as the silver spoons and ceremonial robes preserved in grander museums. The gesture suggests that the daily labor and quiet style of Black women and girls are as historically significant as any general’s uniform.

The Colored Girls Museum is hardly alone in this work—house museums and grassroots cultural spaces across the country have long preserved Black women’s histories—but its focus on contemporary, living “ordinary girls” is unusual. It does not only memorialize the past; it insists on seeing current Black girlhood as something to protect, praise, and study in real time.

A public ritual of protection, praise and grace

On social media, the museum describes itself as “…A Public Ritual for Protection, Praise and Grace. Protection from all harm. Praise for who she is. Grace for our stories.” The language reads less like a mission statement and more like a liturgy, which is fitting: if you spend enough time in the house, the visit begins to feel like a kind of service.

There is protection in the way the docents—often Black women themselves—shepherd visitors through the rooms, inviting questions and laughter but also reminding people to be gentle with the objects, to remember that many of them were once in someone’s private bedroom or bathroom.

There is praise in the way the portraits are hung, eye-level and unapologetic, daring visitors to meet the gaze of Black girls whose faces have too often been stereotyped or discarded.

And there is grace in the way the museum holds complexity: the grief of DuBois’s own loss, the pain of histories of violence and disappearance (one piece, for instance, once invoked the tens of thousands of missing women and girls in the U.S.), alongside scenes of joy—girls in tulle skirts, women laughing on couches, a kitchen table set as if for a cousin’s birthday party.

The work is not without strain. Like many small, community-rooted institutions, The Colored Girls Museum operates without the cushion of a massive endowment or a large full-time staff. Maintaining a 19th-century house, curating new exhibitions, running mobile programs, and engaging schools and universities requires constant fundraising and careful triage of energy. Yet, for nearly a decade, DuBois and her collaborators have kept the doors open, one exhibition and one object at a time.

The future in the front room

On a recent afternoon, a small group of Black girls arrive with their teacher, shuffling a little nervously into the front room with its saturated pink wall and rows of portraits. No one shushes them. A docent invites them to claim the space—sit down, look around, ask whatever they want.

They move from painting to painting, pausing at one that looks eerily like one of them. “She got my hair,” a girl says quietly. A few minutes later, in another room, someone recognizes the same kind of plastic comb her aunt uses on Sunday mornings. The museum’s power is not in a single, dramatic revelation but in these tiny collisions between a life and its evidence.

This is the bet The Colored Girls Museum is making: that if you give Black girls a space that treats their lives as inherently worthy of documentation and display, they will start to see themselves as history-makers, not just history’s subjects.

For now, the museum remains in its Germantown twin, a house constantly in the act of becoming. The exhibitions will change; the objects will shift; new girls will walk up the front path unsure of what, exactly, awaits them on the other side of the door.

But the promise will remain the same—the one embedded in the sign over the porch and in the ritual of crossing that threshold: inside this house, every Colored Girl is already museum-worthy.