KOLUMN Magazine

Three

Kings of

Morehouse

How a grandfather, a father and a son turned one small Black college—along with a church and a bank on Sweet Auburn—into the backbone of a movement.

By KOLUMN Magazine

On a clear Atlanta morning, the bronze Martin Luther King Jr. at Morehouse College is frozen mid-stride, arm lifted toward some invisible horizon above the red-brick chapel that bears his name. Freshmen in navy blazers and slim-cut suits drift past the statue on their way to class; a few glance up, most don’t. It’s the week before midterms, and they move quickly, juggling laptops, headphones and the low-level anxiety that comes with being a “Morehouse man” in the age of student debt, gig work and economic precarity.

A mile or so away, on what was once called “the richest Negro street in the world,” the glass doors of Citizens Trust Bank open onto Auburn Avenue, the historic corridor of Black business, churches and civil rights organizing. Inside, the lobby is hushed, but the posters and marketing copy are loud with memory: photos of marches, churches, corner stores that survived bad decades and worse recessions, and the quiet insistence of a slogan the bank uses these days—Your story is our story.

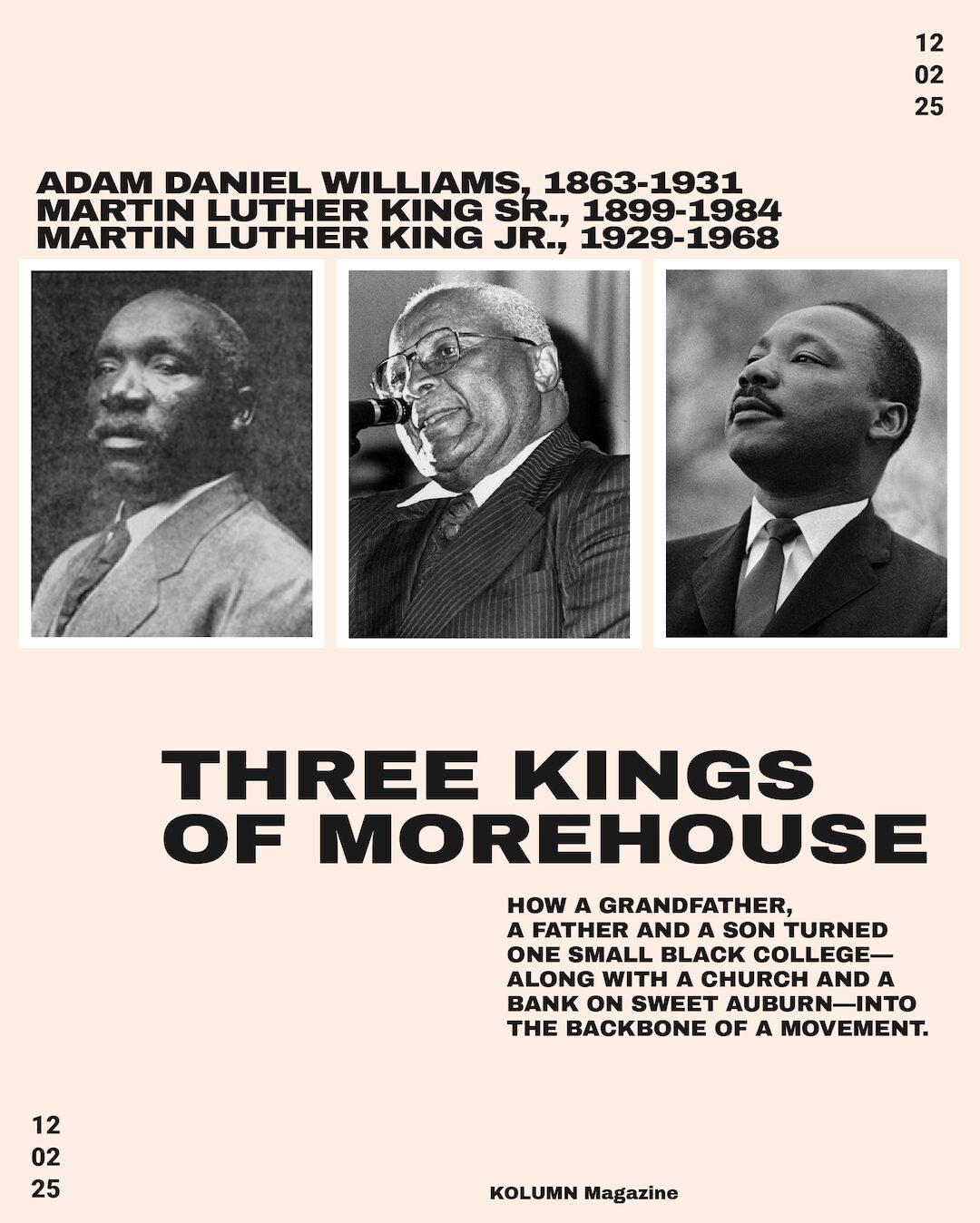

Between the chapel and the branch, between the young men in pressed jackets and the older customers of a century-old Black bank, runs a through-line that is almost singular in American history: three generations of one family—Adam Daniel Williams, Martin Luther King Sr. and Martin Luther King Jr.—all educated at the same small, all-male Black college. Their degrees were more than credentials. For a people boxed out of white universities, voting booths and mainstream capital, a Morehouse diploma was a kind of passport. And like the bankbooks kept at Citizens Trust, it represented a fragile claim on a future that was never guaranteed.

This is the story of how a grandfather, a father and a son carried that Morehouse education back to Sweet Auburn—to a church, a bank and eventually to the nation’s Capitol steps—and how the institutions that nurtured them continue to shape the lives of the people whose paychecks, tithes and savings keep those places alive.

The Late Starter

Adam Daniel Williams did not look like the prototype of a future college man.

Born in 1863 in rural Georgia, the son of formerly enslaved parents, Williams spent his early adulthood doing the work that was available to Black men at the end of the 19th century—manual labor, odd jobs, the small and constant hustles required to stay afloat in a state still haunted by Reconstruction’s collapse.

In his early thirties, already married and a practicing preacher, Williams did something unusual: he went back to school. In 1894, he enrolled at Atlanta Baptist Seminary—what would later become Morehouse College—and immersed himself in theology. was older than most of his classmates, responsible for a young family and a fledgling ministry, yet he spent four years grinding through Greek, scripture and homiletics before graduating from the theological department in 1898.

That decision did more than sharpen his sermons. It tied his family’s destiny to an institution that was only just beginning to imagine itself as a factory for Black male leadership.

A year before Williams enrolled, he had been called to serve as the second pastor of Ebenezer Baptist Church, a small congregation then meeting in a rented space in downtown Atlanta. Under his leadership, the church’s membership grew from 13 to nearly 750 by 1913—a staggering expansion that mirrored the rise of Black Atlanta itself.

Williams moved the church to Auburn Avenue, at the heart of a district that would soon be crowded with Black-owned insurance companies, newspapers, funeral homes and, eventually, a bank. His sermons fused evangelical fervor with a distinctly modern ambition: that Black people should not only be saved souls, but property owners, entrepreneurs and, crucially, educated citizens.

That he took himself—already an established pastor—back to school at 30 was, as one early biographical sketch put it, “the secret of his success.” He was not afraid “to try new things if they ring true and are scriptural.”

Williams’ choice of school mattered. Morehouse, then still called Atlanta Baptist College, sat just west of downtown, part of the cluster of Black institutions that would become the Atlanta University Center. It was a place where the idea of a liberal-arts education for Black men—philosophy, history, classical languages—could coexist with a fierce insistence on social uplift.

When he climbed the graduation platform in 1898, Williams did not yet know that he was inaugurating something larger than his own career. He was, in effect, opening a pipeline: from a red-brick campus on the city’s western flank to a sanctuary on Auburn Avenue, and from there to a network of Black businesses, including a bank that would one day help finance a movement.

King and the Street of Black Capital

By the time a wiry teenager named Michael King stepped off a wagon from Stockbridge, Georgia, into the bustle of Sweet Auburn, the world Williams had helped build was in full swing. Auburn Avenue’s storefronts and second-floor offices formed the commercial spine of Black Atlanta; Fortune magazine would later call it “the richest Negro street in the world.”

Michael—a sharecropper’s son—took a room in the Williams household, boarded with Adam Daniel and his daughter, Alberta. He joined Ebenezer, soaked up the older pastor’s preaching, and, after courting Alberta for years, married into the family in 1926.

The elder Williams pressed his new son-in-law to pursue more schooling. Michael had limited formal education, but he enrolled at Bryant Preparatory School to finish high school and, in 1926, was admitted to Morehouse College’s theology program. He worked days as a mechanic’s helper and a railroad fireman, attending classes whenever he could.

In 1930, he finished a Bachelor of Theology degree at Morehouse—just two years after the school took on its modern name—and soon took over as Ebenezer’s senior pastor following Williams’ death in 1931.

Sometime in the 1930s, he also changed his name. After a trip to Europe and exposure to the legacy of the German reformer Martin Luther, he began calling himself Martin Luther King Sr.; his son, Michael Jr., became Martin Luther King Jr. Around Ebenezer, everyone simply called him “Daddy King.”

His pulpit style was different from his father-in-law’s—louder, more confrontational—but his theology shared the same core conviction: “In this we find we are to do something about the brokenhearted, poor, unemployed, the captive, the blind, and the bruised,” he told fellow clergymen in 1940.

The church stood in the middle of a dense ecosystem of Black institutions, and one of the most important sat just up the street: Citizens Trust Bank. Founded in 1921 with $500,000 in capital, Citizens Trust set out to promote financial stability, small-business development and the ideal of homeownership among Black Atlantans locked out of white banks.

The bank’s presence meant that the men and women who filled Ebenezer’s pews on Sunday could walk their tithes and savings deposits to a Black-owned bank on Monday. Citizens Trust helped churches rebuild after fires, including a devastating blaze at Big Bethel AME in 1923, and it underwrote mortgages, business loans and civic projects that white institutions shunned.

Over time, Martin Luther King Sr. joined the bank’s board, a role later cited by Citizens Trust and by coverage of the contemporary “Bank Black” movement. In the 1950s and ’60s, as civil rights leaders were jailed in Birmingham, Albany and Selma, Citizens Trust helped provide the bail money—“Somebody had to bail them out,” Ray Robinson, the bank’s current chairman, reminded a crowd at a recent historic-marker dedication.

For the bank’s customers—teachers, postal workers, small shopkeepers, and, increasingly, college-educated professionals—the relationship felt like more than an account number. Depositing money there was a statement of faith: in Black institutions, in the possibility of economic citizenship, and in the idea that the same Auburn Avenue that financed their mortgages and car notes could also finance a moral revolution.

Many of those customers had passed through Morehouse. And within the King household on Auburn Avenue, the expectation that the sons would do the same was quietly becoming non-negotiable.

M.L., Fifteen and Restless

In the summer of 1944, a skinny 15-year-old named “M.L.” boarded a northbound train with a group of Morehouse students and headed to the Connecticut tobacco fields. World War II had thinned the college’s enrollment, and Morehouse had begun admitting promising high-school juniors to keep its classrooms full. King passed the entrance exam and enrolled that fall.

The trip north was his first extended encounter with life outside the Jim Crow South. In letters home, he marveled at restaurants where Black and white patrons sat together and trains without “Colored” signs. The money—around $4 a day for picking tobacco—was better than anything available to a teenager in Atlanta, and he sent some home, doing for his parents what they had always done for him.

Back at Morehouse, King was not an academic star. His grades were solid but unspectacular; the King Institute later described his academic record there as “short of what might have been expected.” What mattered more were the worlds that opened beyond the transcript: he sang with the renowned Morehouse Glee Club and in the Atlanta University–Morehouse–Spelman Chorus, and he fell under the influence of Benjamin E. Mays, Morehouse’s sixth president, whose austere demeanor and soaring rhetoric made him a kind of moral north star.

Mays, a former sharecropper’s son himself, used chapel talks to knit together theology and politics. Democracy without justice, he insisted, was a contradiction. It was Mays who helped push King to see the pulpit not as an escape from the world but a platform from which to change it.

King entered Morehouse skeptical of his father’s profession, skeptical of institutional religion itself. By the summer of 1947, at 18, he had decided to enter the ministry. The church, he later wrote, offered “the most assuring way to answer an inner urge to serve humanity.”

In 1948, at 19, he graduated from Morehouse with a B.A. in sociology. That same year, Citizens Trust Bank became the first Black-owned bank admitted to the Federal Reserve System, after having already become the first Black-owned institution insured by the FDIC in 1934.

One institution conferred intellectual and moral capital; the other secured deposits and extended credit. Together, they formed an invisible infrastructure around King’s early adulthood.

He would go on to Crozer Theological Seminary in Pennsylvania and then Boston University, earning a doctorate in systematic theology. But when he returned to Atlanta to co-pastor at Ebenezer in 1960, sharing the pulpit with Daddy King, the route he’d taken was still etched into the city’s physical geography: Westview Drive to Auburn Avenue to Sweet Auburn’s storefronts and bank lobbies, where the civil rights movement was becoming a matter not just of ideals, but of bills, budgets and bail.

Bank Books and Bail Money

The classic photographs of the civil rights era—the dignified faces on buses in Montgomery, the young men at lunch counters in Greensboro, the marchers crossing the Edmund Pettus Bridge—rarely show bank ledgers. But the movement was expensive long before it was iconic.

In Atlanta, Citizens Trust Bank became, as one recent historical marker put it, “sacred ground,” in part because it quietly financed much of the infrastructure that sustained protest. It provided loans to Black churches whose sanctuaries doubled as organizing hubs. It extended credit to small businesses that lost white customers after integrating their counters or hiring Black staff. It was there when leaders needed cash to get people out of jail.

Those interactions were transactional, but they were also personal. In Auburn Avenue’s heyday, church deacons, schoolteachers, college presidents and corner-store owners stood in the same teller lines. The bank’s officers—many of them Morehouse men—sat on the boards of the same institutions that filled the neighborhood: the Atlanta Life Insurance Company, the local NAACP chapter, the colleges of the Atlanta University Center.

When the bank celebrated its centennial in 2021, its own historical materials noted the way customers’ stories and the bank’s story blurred together: the rebuilding of Big Bethel after a fire, the growth of “Sweet Auburn” as a hub of Black enterprise, the postwar boom and the lean years that followed.

In recent years, that intertwined history has been pulled into a new context. After the 2016 police killings of Alton Sterling and Philando Castile, Atlanta rapper Killer Mike used a radio appearance to urge listeners to “bank Black,” singling out Citizens Trust as an institution worthy of their savings. The bank saw thousands of new accounts opened in the weeks that followed.

Cynthia Day, Citizens Trust’s president and CEO, has described the movement not as charity but as a reminder of what the bank had always been: a place where fiscal responsibility and economic empowerment for Black communities were the founding principles.

For some Morehouse students and alumni—many of them juggling federal loans with part-time jobs—the idea of opening an account at a Black-owned bank is both symbolic and practical. It’s a gesture toward the past, when King Sr. sat on the board and deposits helped bail out protesters, and a nod to the present, in which the same institution navigated pandemic-era PPP loans to keep Black-owned restaurants, barbershops and nonprofits from folding.

Those customers’ stories—theirs, not the bank’s—are in many ways the quiet continuation of the King family’s Morehouse legacy: Black Atlantans using whatever tools are available to turn education, faith and financial literacy into some approximation of security.

A Family Transcript

On a single sheet of paper in a teaching packet produced by the National Archives—the genealogy of Martin Luther King Jr.—the Morehouse connection appears almost like a family transcript:

Adam Daniel Williams, class of 1898, Atlanta Baptist College (later Morehouse).

Martin Luther King Sr., class of 1930.

Martin Luther King Jr., class of 1948.

A.D. Williams King (King’s younger brother), class of 1960.

Martin Luther King III, class of 1979.

Dexter Scott King, attended Morehouse from 1979 to 1984.

Taken together, the dates read almost like tree rings: each decade its own layer of struggle and possibility.

By the time Martin Luther King III enrolled in 1975, Morehouse was both an elite HBCU and a symbol. A Washington Post profile noted that he earned a political science degree there in 1979, from “the alma mater of his father, grandfather and great-grandfather, each of whom in turn was pastor of Ebenezer Baptist Church.”

Dexter King followed, studying business administration at Morehouse, though he left before graduating. The campus he walked was already steeped in his father’s memory, full of young men who had never heard King speak live but who wore ties to chapel and recited fragments of Letter From Birmingham Jail in freshman humanities.

Morehouse itself leaned into that inheritance. The college’s promotional materials describe it as a place that produces leaders “well-read, well-spoken, well-traveled, well-dressed and well-balanced”—the famous “five wells”—and point to alumni like King, Spike Lee and Samuel L. Jackson as evidence of that ethos.

Within that messaging, the King lineage functions as both proof and pressure. To be a Morehouse man, students are told, is to inherit a legacy of disciplined minds committed to lives of service and social justice. For some, especially those working two jobs to cover tuition, that can feel more aspirational than real. The college, like many private institutions, has wrestled with questions of affordability, governance and political alignment—as seen in the sharp debates over President Joe Biden’s 2024 commencement address, which some students and faculty opposed on moral grounds, invoking King’s anti-militarism.

Yet the pipeline that began with A.D. Williams’s decision to enroll at a small Baptist seminary in the 1890s remains unusually intact. It connects not just one family but a whole class of Black clergy, educators, doctors, lawyers and entrepreneurs who have passed through Morehouse’s gates and then, often, opened checking accounts at banks like Citizens Trust, tithed at churches like Ebenezer, and leveraged those institutions to carve out space in an economy never designed for them.

Paper, Memory and a College That Owns Its Prophet

In 2006, when King’s children announced plans to sell his personal papers at Sotheby’s, Atlanta nearly lost its most famous native son a second time—this time to the private market. A coalition led by then-mayor Shirley Franklin scrambled to raise $32 million to purchase the documents and keep them in the city, ultimately placing them at King’s alma mater, Morehouse College.

The resulting Martin Luther King Jr. Collection, housed at the Robert W. Woodruff Library and curated in partnership with Boston University and Stanford’s King Institute, spans King’s life from his days as a Morehouse student to the last years of his ministry. It includes sermon drafts, letters from jail, typed speeches annotated in his looping hand—thousands of pages of a mind at work.

For scholars and visitors, the collection offers granular proof of something Morehouse has long claimed: that the intellectual and moral architecture of the modern civil rights movement was, in part, constructed on that campus. The documents show King wrestling with theologians he first encountered in college, invoking Mays’s admonitions, and revising speeches whose cadences echo the chapel talks he once sat through as a teenager.

The papers are also reminders of how materially rooted all that idealism was. There are letters from donors, financial statements from the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, travel itineraries that reveal the cost of moving a small band of organizers around the country. Some of those expenses, directly or indirectly, ran through banks like Citizens Trust; others were covered by Black churches that, in turn, depended on Black banks to hold their funds and finance their buildings.

So when current Morehouse students file past the statue outside the chapel, smartphones in hand, tap-paying their way through the day with debit cards that may or may not bear the logo of a Black-owned bank, they’re moving through a campus that is both archive and pipeline. Their presence is as much a part of the King legacy as the bullet-scarred pulpit at Ebenezer or the ledgers in Citizens Trust’s vaults.

A Quiet Continuity

The grandeur of the King story—the marches, the speeches, the assassination—can make everything that came before Morehouse, and everything that has followed at Morehouse, seem like prelude or coda. But the generational arc from Adam Daniel Williams to Martin Luther King Sr. to Martin Luther King Jr. is, among other things, a story about institutions: a college that trained Black men for leadership when few other pathways existed; a church that turned that training into moral authority; and a bank that converted that authority, and the trust of its customers, into the capital needed to keep a movement going.

It is also a story about ordinary people: the Morehouse students who shared tobacco-field barracks with a teenage King in Connecticut; the congregants who put dollar bills in collection plates on Sunday and deposited their wages at Citizens Trust on Monday; the small-business owners who, decades later, would line up to open new accounts during the #BankBlack surge, some of them citing King by name as a reason to move their money.

Those customers—those bank clients, alumni donors, scholarship recipients—are the ones who quietly sustain the legacy the King family built with its Morehouse diplomas. Their lives lack the drama of a Lincoln Memorial or a Nobel Prize ceremony, but they are where the lofty rhetoric lands: in mortgage payments made on time, in tuition checks sent to the bursar’s office, in tithes that keep a sanctuary open and a food pantry stocked.

On that Atlanta morning, as the sun climbs higher above the chapel and the lobby lights flick on at Citizens Trust, the connections between those places are invisible to most people moving through them. But they’re there, written into the city’s geography and into the ledgers—academic and financial—that three generations of Kings and countless ordinary customers have signed.

The statue on the plaza points upward, but the real legacy of the Kings at Morehouse, and of the Black institutions that held them, runs laterally: across decades, across families, across the everyday transactions that have always underwritten the long, unfinished work of freedom.