KOLUMN Magazine

What

Elizabeth

Catlett

Saw

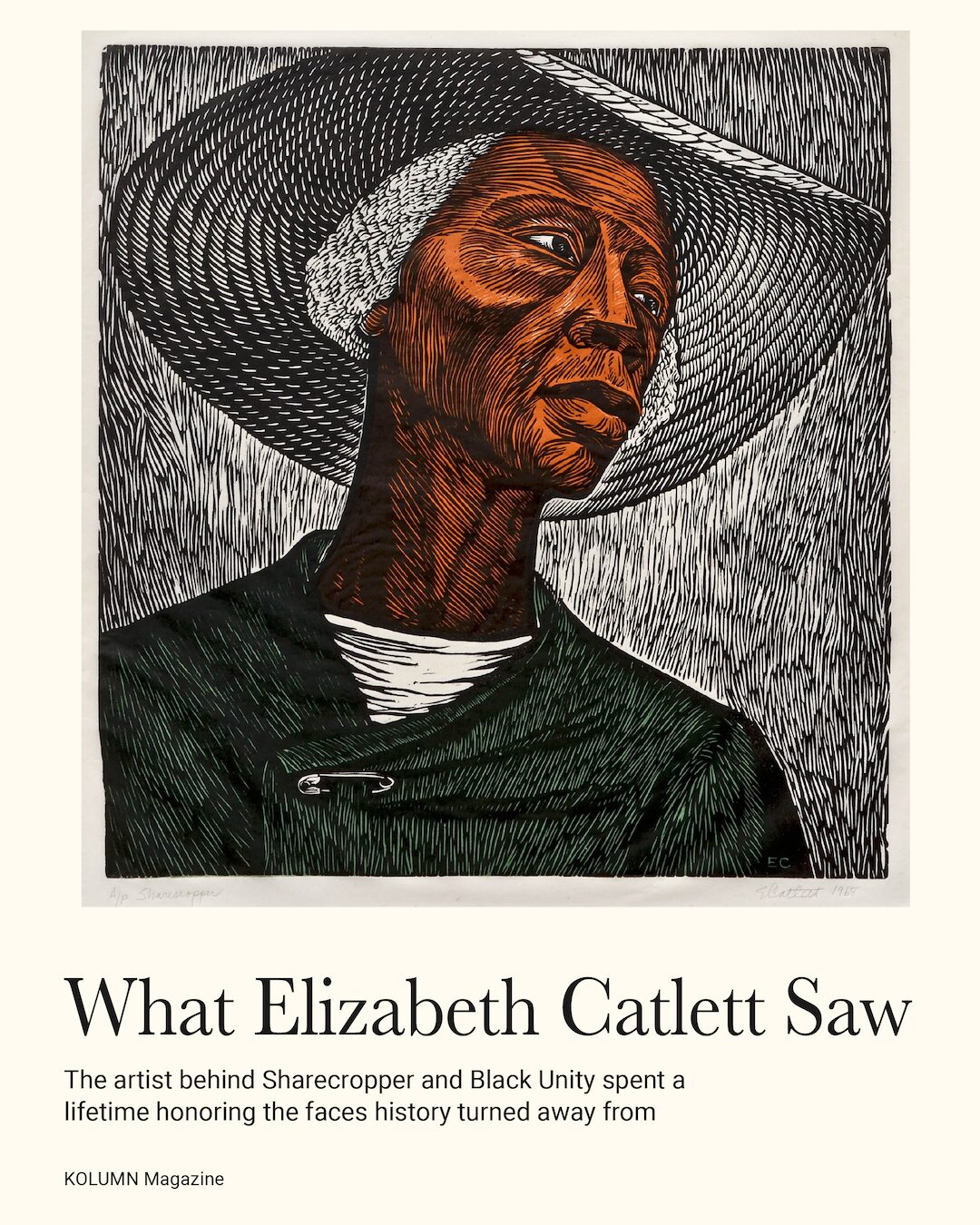

The artist behind Sharecropper and Black Unity spent a lifetime honoring the faces history turned away from

By KOLUMN Magazine

On a wooden pedestal in a quiet gallery, a block of mahogany has been coaxed into something like a vow. The sculpture—an abstracted Black face that is also a clenched fist—seems to meet the gaze of every visitor who drifts past it. This is Black Unity, carved in 1968 by Elizabeth Catlett, a woman who liked to say that she wanted her art “to service Black people—to reflect us, to relate to us, to stimulate us.”

Across town, in another museum, a much smaller work anchors an entirely different kind of crowd. Here, visitors lean in close to a linoleum print of a single woman in a straw hat. Her coat is pinned shut with a safety pin; her eyes are wary, tired, unflinching. The caption reads simply: Sharecropper, 1952.

Together, the two works trace the arc of Catlett’s life: from a Jim Crow childhood in Washington, D.C., to her self-chosen exile in Mexico; from the intimate portrayal of anonymous laborers to monumental symbols of Black power. Her story is one of borders crossed—between countries, between mediums, between aesthetics and politics—and of an artist who insisted that beauty could never be separated from justice.

A life shaped by absence and insistence

Elizabeth Catlett was born in 1915, the granddaughter of enslaved people, into a household that already understood how absence could structure a life. Her father, a mathematics teacher at Tuskegee Institute, died before she was born. Her mother, a trained teacher, juggled multiple jobs in Washington, D.C., to raise three children on her own.

From the beginning, Catlett understood that talent would not be enough. As a teenager she earned a scholarship to the Carnegie Institute of Technology in Pittsburgh, only to be rejected when the school discovered she was Black. She enrolled instead at Howard University, where her teachers included the painter Loïs Mailou Jones and the philosopher Alain Locke, the so-called “dean” of the Harlem Renaissance, who encouraged students to mine Black life for serious artistic subject matter.

At Howard, the young sculptor absorbed an education in both form and urgency. She studied with James Porter, who was mapping an African American art history that mainstream museums ignored, and she watched older peers navigate the cramped professional field that awaited them. What did it mean, she wondered, to make art when Black bodies were still segregated by law, when Black women did the least heralded, least protected work in the country?

The question followed her to the University of Iowa, where she became the first Black woman to earn an MFA in sculpture in 1940. There she studied with the regionalist painter Grant Wood, famous for American Gothic. Wood urged his students to root their work in the lives of “their own people,” advice Catlett took literally. Her thesis sculpture, Mother and Child, carved in limestone, presented an African American mother in a tender, protective embrace—an early statement of the theme she would return to for decades: Black women as the center of the story, not its backdrop.

Teaching against the color line

If the art world offered few openings to a young Black woman, Catlett made her own, often in the classroom. In the early 1940s she became chair of the art department at Dillard University, a historically Black college in New Orleans. There, she staged one of her first quiet rebellions.

When a major exhibition of Pablo Picasso’s work came to the city’s museum, it was installed in a building at the center of a whites-only park. Black New Orleanians could not legally enter. Catlett refused to accept that her students would be barred from seeing it. She negotiated with the museum to open on a day when it was closed to the public, then loaded her students onto a bus and marched them through the empty park to the front door.

The episode prefigured the way she would live the rest of her life: testing every barrier, bending every rule that seemed to consign Black people to the margins.

Southward, then south of the border

In 1946, newly married to the artist Charles White and armed with a Julius Rosenwald Fellowship, Catlett proposed an ambitious project: a series of prints and sculptures depicting Black women—sharecroppers, domestics, mothers, activists. The fellowship allowed her to travel to Mexico City, where she expected to spend a brief period studying printmaking. Instead, she found her artistic home.

Mexico in the 1940s was a hotbed of leftist creativity. At the Taller de Gráfica Popular (People’s Graphic Workshop), Catlett joined a group of artists committed to making affordable art for workers and peasants—posters, broadsides, and prints that could be wheat-pasted on city walls or sold cheaply in markets. She learned to cut linoleum blocks with a ferocity that echoed the rhetoric around her: slogans against fascism, portraits of labor leaders, scenes of everyday struggle.

Her politics—and her associations—did not go unnoticed in the United States. During the Red Scare, Catlett’s activism and affiliation with the leftist workshop led U.S. officials to label her an “undesirable alien.” In 1962, after she had separated from White and married the Mexican painter Francisco Mora, she became a Mexican citizen. For years she was barred from re-entering the country of her birth. Her U.S. citizenship would not be restored until 2002.

Exile shaped her sense of solidarity. In her prints she portrayed Mexican farmers and Black American activists with the same attention to posture and fatigue; in her sculptures, she began to fuse African and Indigenous American influences into smooth, monumental forms.

The woman in the straw hat

Among the linoleum blocks she carved in Mexico, one image in particular refused to leave her. Sometime around 1952, Catlett etched the face of a Black woman into linoleum: high cheekbones, furrowed brow, a mouth set in a line that might be resignation or resolve. The woman’s broad straw hat tilts toward us; her lightweight coat is held shut with a safety pin.

Titled Sharecropper, the print depicts a worker caught in the agricultural system that had replaced slavery with a different kind of trap—Black families renting land from white landowners, paying in crops instead of cash, rarely escaping debt. The system kept thousands of Black Southerners in a near-feudal poverty well into the 20th century.

Catlett had not grown up on a farm, but she had watched Black domestic workers stream in and out of houses in Washington, D.C., and she had traveled through the South enough to understand how labor and land were braided together. In Sharecropper, she condensed a history of exploitation into the tilt of a head and the texture of a coat.

The print’s power lies in its contradictions. Against the dense cross-hatching that defines the woman’s skin and hat, her eyes emerge with startling clarity—not pleading, not defeated, but level. Critics at the time noted the way the sharp gouges of the carving tool translate into a weathered face, the furrows etched like rows of cotton.

Catlett continued to return to the plate over the decades, experimenting with color—one version in deep green and black, another in earthy browns. A fellow artist at the Taller de Gráfica Popular printed early editions; later, Catlett would oversee new runs herself, treating the image almost like a living testimony that needed to be restated in each era.

Today Sharecropper hangs in museums from Chicago to Minneapolis to St. Louis. Wall labels emphasize its “lifelong concern for the marginalized and the dignity of women,” as one museum puts it. But in front of the print, visitors often fall silent, as if sensing that they’ve stepped into a private encounter. The anonymous woman is both specific and emblematic: she might be someone’s grandmother, or the neighbor who took in laundry, or the woman on the bus who never spoke but always watched.

Sculpting solidarity

If the prints delivered Catlett’s politics in sharp relief, her sculptures carried a slower, more contemplative charge. She once acknowledged a kind of division of labor in her practice: sculpture for form, printmaking for social commentary.

In the 1950s and ’60s, working in wood, stone, and bronze, she created a succession of figures that stretched and compressed the human body: elongated necks, simplified faces, torsos that seemed to sway even at rest. Many depicted mothers and children, their surfaces sanded to a satin sheen, their limbs reduced almost to symbols. The curves and voids echo both African sculpture and the sinuous lines of Mexican modernism.

Black Unity, carved from cedar in 1968, condenses that vocabulary into a single block. One side presents two stylized faces pressed together; the other, a raised fist. Viewed straight on, it becomes a literal emblem of the era’s Black Power movement; seen in the round, it resolves into a meditation on collectivity—individuals fused into a single, resistant mass.

She brought the same balance of dignity and defiance to her portraits of specific figures. Her bronze bust of Martin Luther King Jr., created in the 1980s for a competition to place a sculpture of King in the U.S. Capitol, shows the civil rights leader not as an orator mid-speech but as a man in reflective pause, brows knit, lips slightly parted. The work, recently brought out of storage for prominent display in San Francisco, has been hailed by curators as one of the most affecting sculptural portraits of King, in part because it refuses to smooth away his fatigue.

Another series, including works like Stepping Out and numerous mother-and-child figures, translates ordinary gestures—walking, holding, leaning—into monumental grace. To stand before them is to confront bodies that have been carved, quite literally, out of histories that tried to render them invisible.

An exile’s return—on her own terms

From her home and studio in Cuernavaca, Mexico, Catlett lived a kind of double life. By day she taught sculpture at the National School of Plastic Arts, eventually heading its department. In the evenings she carved and printed, her work traveling across borders even when she could not. She followed the civil rights movement from afar, contributing images like Malcolm X Speaks for Us to activist causes; she watched as Black feminists in the United States began to find in her work a mirror of their own politics.

When the U.S. finally restored her citizenship in the early 2000s, Catlett chose to remain in Mexico, the country that had given her both a home and a political language. By then, museums that had long ignored her were beginning to reconsider. Her prints and sculptures entered major collections; younger artists cited her as a precursor in conversations about race, gender, and labor.

Today, a wave of retrospectives—from the Mattatuck Museum in Connecticut to the National Gallery of Art in Washington—presents Catlett not as a niche figure but as a central artist of the 20th century, whose work crosses national and disciplinary lines. These exhibitions emphasize her dual identity as an American and Mexican citizen, her role as a civil rights activist, and her refusal to separate aesthetics from ethics.

In gallery texts and curatorial essays, her art is often described as “timely,” though it might be more accurate to say that the times have finally caught up. When viewers stand before Sharecropper now, many bring with them stories of migrant labor, wage theft, and agricultural exploitation that echo the sharecropping system the print memorializes. When they circle Black Unity, they do so against a backdrop of renewed Black Lives Matter protests and debates over monuments and public space.

The stories that remain

Elizabeth Catlett died in 2012 at the age of 96, in the country she had chosen. Yet in many American cities, the first encounter people have with her is as sudden and intimate as a handshake: a face in a print, a curve of polished wood that feels like a shoulder.

Her legacy is not just the images she left behind but the insistence they carry—that Black women’s lives, labor, and leadership are worthy of the most serious artistic attention. In Sharecropper, the anonymous woman in the straw hat stands in for a whole class of people tied to the land yet shut out of its wealth. In the sculptures, the rounded backs and upturned chins make visible a resilience that is neither sentimental nor naïve.

Catlett once described her purpose as giving people “images of themselves that they could live by.” In that sense, her work still behaves like a kind of quiet mirror. Whether it is the farmer in a straw hat, the mother cradling a child, or the faceted fist of Black Unity, the figures she carved and printed keep doing what she set out for them to do: reflecting back the dignity that history tried, and failed, to erase.