Under the

Birdland Marquee

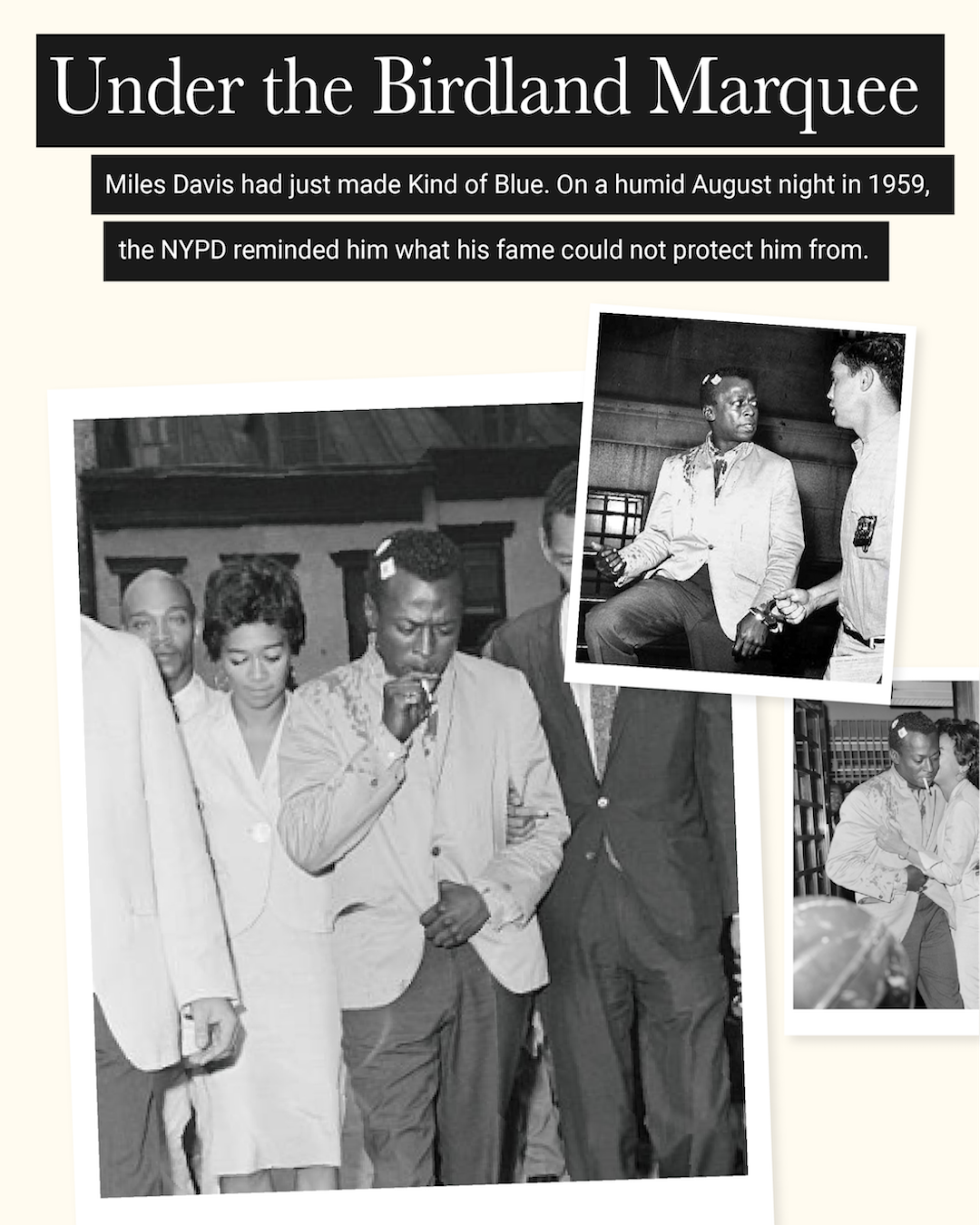

Miles Davis had just made Kind of Blue. On a humid August night in 1959, the NYPD reminded him what his fame could not protect him from.

By KOLUMN Magazine

Under the blue glow of the Birdland marquee, Miles Davis was doing something utterly ordinary: leaning against a brick wall, smoking a cigarette, his horn cooling off inside. A few minutes earlier he’d walked a young white woman to a cab and watched it disappear into the late-August haze of Midtown Manhattan. It was the summer of 1959, the year Kind of Blue came out and the year New York liked to tell itself it was sophisticated enough to be past certain old brutalities.

Then a white patrolman stepped up and told one of the most famous musicians in America to move along.

Miles said no.

What happened over the next several minutes — the blows to the head and stomach, the blood soaking his light-colored suit, the flashbulbs catching him being marched through a station house — would become one of the most widely documented acts of police violence against a Black celebrity in the pre-civil-rights-era North. It unfolded on a sidewalk in front of a jazz club where his name was literally on the canopy, and where inside, the band kept playing without him.

“Kind of Blue” Summer

To understand why the beating outside Birdland landed with such force, you have to start with how high Miles Davis was standing that summer.

In March and April, he had led a sextet — John Coltrane, Cannonball Adderley, Bill Evans, Paul Chambers, Jimmy Cobb — through two brief sessions at Columbia’s 30th Street Studio. The result, Kind of Blue, would be released on August 17 and quietly begin its slow march toward becoming the best-selling jazz album of all time.

It was a season when jazz seemed to be re-writing the rules all at once. The same year saw Ornette Coleman’s The Shape of Jazz to Come, Charles Mingus’s Mingus Ah Um and Dave Brubeck’s Time Out. In the chronologies of 1959, one line sits incongruously among the album releases: “August 25: Between sets at Birdland in New York City, Miles Davis is beaten by police and jailed.”

Birdland itself, tucked at Broadway and 52nd Street, called itself “The Jazz Corner of the World.” Its tables drew a mix of jazz obsessives and Midtown glamour — Frank Sinatra and Ava Gardner, Marlene Dietrich and Joe Louis, movie stars and prizefighters threading between the cramped tables. Like much of the jazz world, it ran on a paradox: Black performers on stage, a largely white audience out front, and police officers patrolling the sidewalks outside.

On August 25, Davis spent the afternoon recording a Voice of America broadcast for the armed forces, then headed to Birdland for a multi-set engagement. Inside the club he was very much the star — leading his group, announcing numbers, walking offstage with the casual authority of a musician at the height of his powers.

Outside, that authority vanished.

The Walk to the Cab

The outlines of the night are well-established in court records, contemporary news accounts and Davis’s own autobiography. The precise tone of each exchange is harder to reconstruct, but most sources agree on the sequence.

Sometime after midnight, Davis stepped out of the club between sets and escorted a “blonde-haired woman,” usually described as a young white fan or acquaintance, to a taxi. He watched the cab pull away and then returned to his spot just outside the club’s entrance. It was a familiar ritual: smoke, talk with fans, sign a program or two while keeping an eye on the time.

A uniformed patrolman, later identified as Gerald Kilduff, approached and told Davis to “move on.” In later telling, Davis said he replied, in effect: I’m working here. My name is on the marquee. According to the summary on his official biography, Miles: The Autobiography (1989), and subsequent histories, he refused to leave the doorway he regarded as part of his workplace.

Davis recounting:

I had just finished doing an Armed Forces Day broadcast, you know, Voice of America and all that bullshit. I had just walked this pretty white girl named Judy out to get a cab. She got in the cab, and I’m standing there in front of Birdland wringing wet because it’s a hot, steaming, muggy night in August. This white policeman comes up to me and tells me to move on. At the time I was doing a lot of boxing and so I thought to myself, I ought to hit this motherfucker because I knew what he was doing. But instead I said, “Move on, for what? I’m working downstairs. That’s my name up there, Miles Davis,” and I pointed to my name on the marquee all up in lights. He said, “I don’t care where you work, I said move on! If you don’t move on I’m going to arrest you.” I just looked at his face real straight and hard, and I didn’t move. Then he said, “You’re under arrest!” He reached for his handcuffs, but he was stepping back. Now, boxers had told me that if a guy’s going to hit you, if you walk toward him you can see what’s happening. I saw by the way he was handling himself that the policeman was an ex-fighter. So I kin of leaned in closer because I wasn’t going to give him no distance so he could hit me on the head. He stumbled, and all his stuff fell on the sidewalk, and I thought to myself, Oh, shit, they’re going to think that I fucked with him or something. I’m waiting for him to put the handcuffs on, because all his stuff is on the ground and shit. Then I move closer so he won’t be able to fuck me up. A crowd had gathered all of a sudden from out of nowhere, and this white detective runs in and BAM! hits me on the head. I never saw him coming. Blood was running down the khaki suit I had on. Then I remember [journalist] Dorothy Kilgallen coming outside with this horrible look on her face — I had known Dorothy for years and I used to date her good friend, Jean Bock — and saying, “Miles, what happened?” I couldn’t say nothing. Illinois Jacquet [the saxophonist] was there, too.

Witnesses quoted in newspaper accounts and later histories said Davis remained where he was, explaining that he was on a break between sets. The officer, these witnesses said, struck first, jabbing him in the stomach with a nightstick. To some onlookers, it looked less like a lawful arrest than an officer enraged at a Black man refusing to shrink.

Traffic on 52nd Street began to slow as passers-by realized who was being confronted. Birdland’s doorman and club staff tried to explain that Davis was the headline act; patrons spilled onto the sidewalk. Inside, the band was due to start again.

Then a plainclothes detective came in from behind.

As Davis told it years later, he never saw the detective before the blow landed. A heavy object smashed into the back of his head — some sources say a blackjack, others a baton — opening a wound that sent blood streaming down his light khaki suit.

Within minutes, squad cars converged. Two detectives held back the gathering crowd; another helped shove the bleeding trumpeter into a patrol car. Sirens drowned out the arguments, the pleas, the chorus of “He didn’t do anything” from fans on the sidewalk.

“Jazz Trumpeter in Joust With Cops”

The next stop was the Midtown North precinct on West 54th Street. There, still bleeding, Davis was booked on charges of disorderly conduct and assaulting an officer. Only after the formalities of fingerprinting and paperwork was Davis taken to St. Clare’s Hospital, where a doctor stitched the scalp wound — five to ten stitches, depending on the account — before he was returned to the station and held in a cell.

By morning, the image of the world-famous trumpeter, jacket darkened with dried blood, being led through the station house was moving across news wires. A contemporaneous story in the Sarasota Journal ran under the headline “Jazz Trumpeter Miles Davis In Joust With Cops,” framing the incident as a kind of mutual scrap between entertainer and police. Meanwhile, the Baltimore Afro-American, a leading Black newspaper, ran a more pointed headline: “Was Miles Davis Beaten Over Blonde?”

Those dueling framings encapsulated a racial divide in how the beating was seen.

In Davis’s own account, the assault was nakedly racist, fueled by seeing a Black man escort a white woman and then refuse to disappear. Later he would recall realizing that, surrounded by white witnesses, he could not rely on “justice” — a bitter conclusion that echoed in his conversations for decades.

In police reports and much of the mainstream white press, the story emphasized the officer’s claim that Davis had refused lawful orders and “shoved” the patrolman, necessitating force. The charges — disorderly conduct and third-degree assault — turned the musician into the legal aggressor in the official narrative.

At Birdland, the band finished the night without its leader.

A City With a History

The beating didn’t happen in a vacuum. New York in the 1950s was already thick with grievances over police treatment of Black residents.

From Harlem to Bedford-Stuyvesant, African Americans had often reported being stopped, searched and beaten with little recourse. Activists and clergy documented case after case in which Black New Yorkers emerged from police encounters with bruises or worse, only to find their complaints dismissed.

For Black musicians, the tension could be particularly acute. They spent their nights in clubs that catered to white audiences and depended on police tolerance to keep doors open and crowds flowing. Yet, as one historian of the jazz era has noted, the men in blue often saw those same musicians as suspect — “hipsters” and “characters” to be kept in line rather than artists at work.

Davis was hardly the only Black musician who had stories of rough handling, but his fame made his case unusually visible. Within weeks, the British music weekly Melody Maker splashed a photo of his battered head across its front page under the caption “THIS IS WHAT THEY DID TO MILES DAVIS,” a rare moment when police brutality in the United States was publicly denounced in an overseas jazz paper.

In a sense, the episode anticipated later, more organized campaigns against New York police violence — the protests over the 1964 killing of 15-year-old James Powell in Harlem, the outcry decades later after the deaths of Amadou Diallo and Eric Garner. Historians of the city’s policing note that Black New Yorkers had been documenting such abuses since at least the 1940s, but their efforts were often ignored or punished.

Miles Davis’s battered face briefly broke through that silence.

The Courtroom and the Cost

Legally, the case moved slowly. Davis was released on bail — contemporary sources list it in the neighborhood of $1,000 — and returned to work. In January 1960, after months of adjournments, he was acquitted of disorderly conduct and third-degree assault.

The court found that the state had not proved he had attacked the officer. For Davis and many of his fans, the acquittal simply acknowledged what the crowd outside Birdland had insisted that night: the violence had flowed in one direction.

But the legal victory did little to address the deeper harm.

“Changed my whole life and whole attitude again,” Davis later said of the beating, “made me feel bitter and cynical again when I was starting to feel good about the things that had changed in this country.” According to biographers, he became even more guarded in public, more suspicious of authority, and increasingly outspoken in his contempt for the police. One critic would later describe his posture toward law enforcement, half-jokingly and half-seriously, as a kind of permanent scowl.

Some jazz historians argue that the Birdland assault marked an inflection point in his music as well. The creative arc that had risen through Milestones and Kind of Blue seemed, for a few years, to flatten. One study of his later electric period notes that “extramusical dramas” — including the beating and later a 1969 shooting incident — could send him into lengthy artistic lulls. The line between psychological trauma and musical innovation is impossible to draw cleanly, but in Davis’s own narrative, that night on 52nd Street is a pivot.

The photos, too, lingered. Decades later, as online archives and social media platforms digitized old prints, the images resurfaced: Miles in handcuffs, jacket stained, eyes half-lidded, a policeman’s grip on his arm. Clips from documentaries re-circulated his account. The scene began appearing in timelines of “famous moments in jazz history” and in explainer pieces about the long history of police brutality against Black Americans.

Davis also recounted in his autobiography that he was prepared to sue the New York police department, but his attorney failed to act before the statute of limitations expired. “I was madder than a motherf—er,” he wrote in Miles, “but there wasn’t nothing I could do about it.”

Birdland as Metaphor

Today, it’s easy to mythologize Birdland — to see it only as the place where modern jazz came of age, where Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie and Thelonious Monk remade American music. The club’s marketing helped this, printing “At the Jazz Corner of the World” on menus and handbills, the sort of phrase that turns geography into legend.

But the sidewalk scene outside on August 25, 1959, resists myth. It is stubbornly ordinary in its mechanics: a white officer orders a Black man to move; the Black man asserts a right to stay; force follows.

The particulars — the contract in Davis’s pocket, the album climbing the charts, the name on the marquee — give the story its sting. This was not an anonymous teenager in a back alley but one of the most acclaimed musicians in the world, standing in front of his workplace on a night when he had just recorded a patriotic broadcast for American troops. That even he could be clubbed, arrested and charged points to a hierarchy that the courts and the critics and even the music could not undo.

Writers looking back from the vantage point of the Black Lives Matter era have seized on that irony. A PBS “American Masters” essay, published in 2020 amid nationwide protests, argued that “even fame could not protect Miles Davis from police violence,” seeing in his story a precursor to more recent incidents involving Black athletes and entertainers. Another retrospective called the assault “a rare instance in which police brutality against a Black celebrity was widely covered,” suggesting that countless similar cases involving lesser-known people never made it past a police blotter.

Birdland, in that reading, becomes a kind of stage on which the promises and failures of midcentury liberalism played out. Inside, integrated audiences applauded Black virtuosity; outside, state power still treated Black bodies as disposable.

Echoes on the Street

More than sixty years after that humid night, the story of Miles Davis and the NYPD circulates in fragments: a grainy black-and-white photo in a jazz subreddit; a captioned image in a police-violence explainer; a paragraph in a biography; a wistful aside in a musician’s memoir about the dangers of leaving a club after midnight.

In jazz circles, the incident is sometimes treated as an object lesson in the limits of respectability. No matter how tasteful the suit, how boundary-breaking the art, how impeccable the résumé, the wrong encounter on the wrong sidewalk could reduce a star to a defendant.

For historians of New York, it is a point on a continuum — one case among thousands in the long record of Black New Yorkers’ fraught encounters with the police. For activists, it is a reminder that high-profile cases can galvanize outrage but rarely fix systems.

For Miles Davis, it was personal. The scar on the back of his head healed. The bitterness did not. In the years that followed, as he pushed jazz into new, electric territories, the memory of that night remained a shadow just offstage: a reminder that for all the adoration inside the club, the rules on the sidewalk had not changed.

The Birdland marquee promised that the jazz inside was the sound of a modern, sophisticated America. The blood on the pavement outside told another story.