An honest and loving relationship that survived the closing notices.

An honest and loving relationship that survived the closing notices.

By KOLUMN Magazine

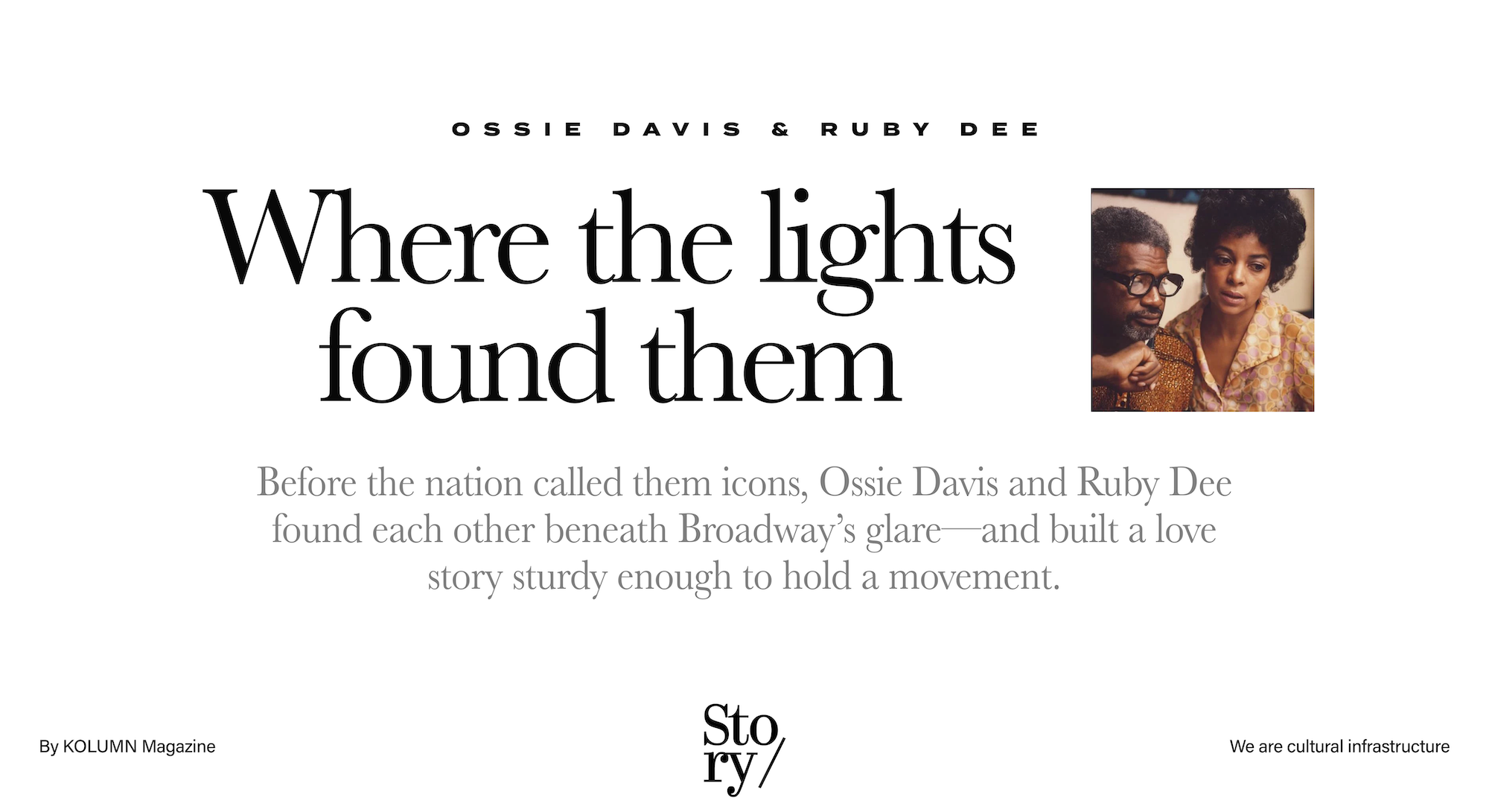

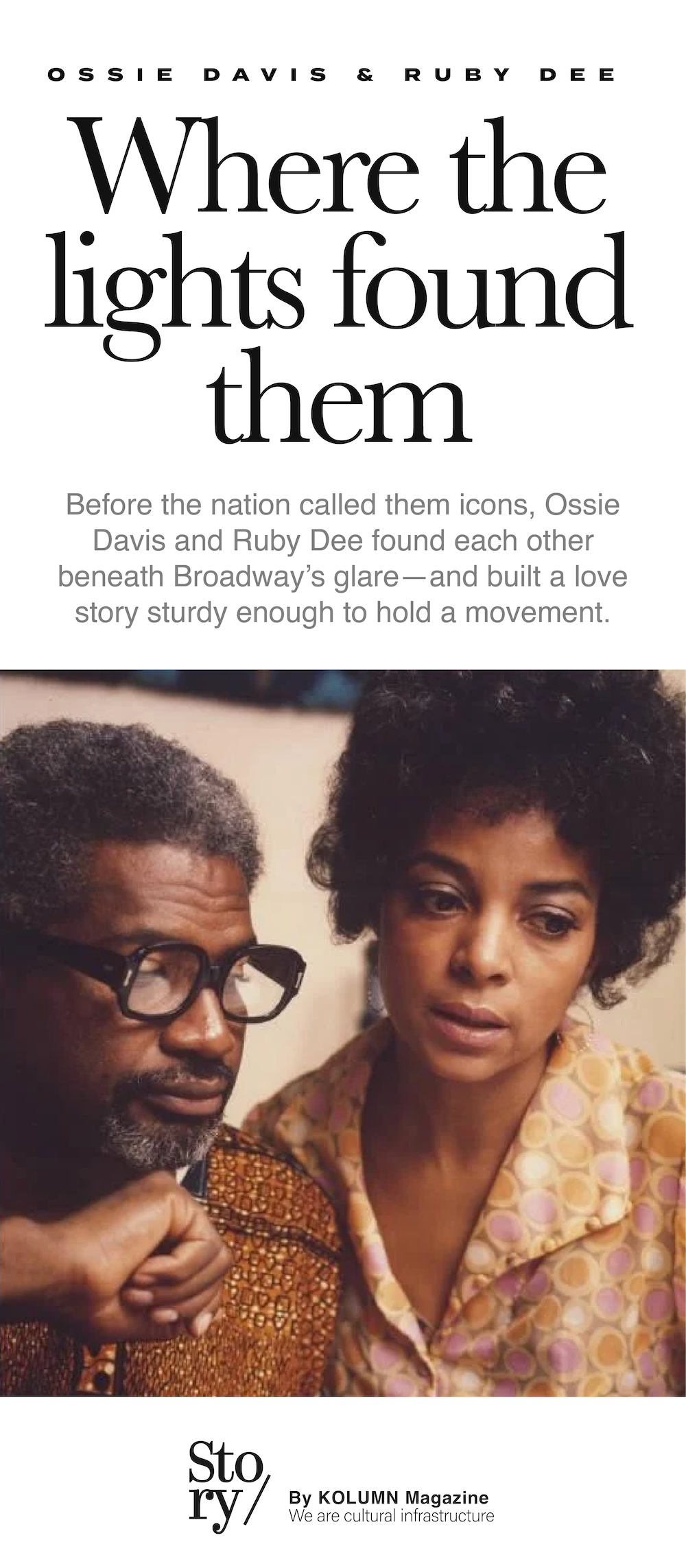

The story of Ossie Davis and Ruby Dee is often told as if it were inevitable: two gifted actors, two formidable intellects, two civil rights voices, fused into one of the most recognizable partnerships in American cultural life. But their beginning—like most beginnings—was simpler than legend often demands. It happened in the working world, among understudies and casting notices, nerves and ambition.

In 1946, Broadway was still a gatekept island, and the American theater’s main currents rarely made room for Black life except as caricature or constraint. Yet that year a production arrived with unusual bluntness: “Jeb,” a drama centered on a Black World War II veteran who returns home to confront white supremacist terror. For Broadway, the subject was volatile; for Black performers, it was familiar in the way danger is familiar—known, mapped, and still capable of surprise. The show’s run proved brief, but the work it did inside one rehearsal room proved durable. It put Ossie Davis in the title role, and it brought Ruby Dee into the same orbit—reported in multiple accounts as understudy and performer connected to the production—long enough for recognition to turn into curiosity, and curiosity to turn into a covenant.

To write about how Davis met Dee is to write about more than a “cute” origin story. Their meeting sits at the intersection of craft and survival, of love and labor, of private choice and public demand. Their marriage would become a kind of national shorthand—two artists who seemed, to admirers, inseparable; two activists who made celebrity behave like responsibility. But that marriage was also, by their own accounts and later reporting, complicated: shaped by desire, by ego, by political pressure, by the sheer time it takes to remain alongside another person through changing selves. Even their myth has seams—places where the stitching shows.

Before the first scene: Two routes to the same stage

By the time “Jeb” brought them into contact, both had already been moving toward theater as if pulled by gravity. Dee, born Ruby Ann Wallace, came up through Harlem’s cultural infrastructure and the American Negro Theatre—an institution that, for a generation of Black performers, functioned as both training ground and refuge. Stanford’s Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute describes her early path in terms that underline the seriousness of her preparation: she joined the American Negro Theatre while studying, and she was accumulating stage experience before “Jeb” placed her near Davis’s line of sight.

Davis, for his part, was arriving at Broadway in a moment when a single role could define whether you became employable or disposable. “Jeb” represented a debut and a wager: a play asking mainstream audiences to sit with the violence they preferred to imagine as regional, distant, or finished. A Washington Post profile years later would frame the production as “risky and novel” for Broadway, placing the tragedies of racism “right there on the stage.” Davis played the lead. The show’s commercial fate—closing quickly—did not negate what it meant to be there, to do that work, in that room, in that year.

If their eventual partnership can feel prewritten, it may be because both were, even then, oriented toward the same questions: what can Black art demand? What does it cost? Who pays? “Jeb” was not simply a job; it was a statement, and statements have consequences—especially for Black performers whose careers were perpetually one canceled contract away from crisis. In such conditions, intimacy can move quickly not because it is rushed, but because life is. The stakes do not wait.

The first meeting: “Jeb,” the audition room, and the strange lightning of attention

Reported accounts vary slightly in the details—whether you date their first encounter to an audition in 1945 or to the Broadway production in 1946—but the center holds steady: “Jeb” is the location where their lives intersected in a decisive way. The Guardian, in Ruby Dee’s obituary, reported that Davis and Dee met when she auditioned for “Jeb,” a process that brought her into contact with Davis, who was starring in the play.

Other reputable summaries align on the same core fact: their meeting occurred in connection with “Jeb,” and it happened at the dawn of their public trajectories. Stanford’s King Institute entry states plainly that in 1946 Dee met Davis when he starred in “Jeb,” describing the play’s plot as a returning veteran facing down the Ku Klux Klan, and placing Dee in proximity to the production as an understudy.

Archival collections strengthen the reporting with material evidence. The New York Public Library’s finding aid for the Ossie Davis and Ruby Dee papers notes that programs exist for the 1946 production of “Jeb,” identifying it as the production where they first met and collaborated. The phrasing matters: “met” and “collaborated” are paired, as if the archive itself is telling you that the personal and professional were never truly separable for them.

The Washington Post’s 2004 feature on the couple places the moment in a broader cultural frame: “In 1946, they both reached Broadway in ‘Jeb,’” noting the production’s venue and its thematic audacity. The detail is not just scene-setting; it explains the kind of pressure that might bond two young performers quickly. A play that confronts the Klan on a Broadway stage is, in its own way, a declaration of where you stand. To be in that play is to be, at minimum, adjacent to that declaration.

And then there is the human element: the impressions, the vanity, the misjudgment that makes a later love story feel earned rather than ordained. A Washington Post obituary for Dee quoted her recounting that it was not love at first sight—she saw Davis’s photo in the paper as the actor cast in the lead and made a snap, class- and region-inflected assumption about him, only to discover he was “an intellectual.” It is a revealing recollection because it shows Dee, often remembered as dignified and measured, admitting to the quick prejudice of her own glance—and then showing how quickly that glance could be corrected by conversation, by presence, by the facts of a person.

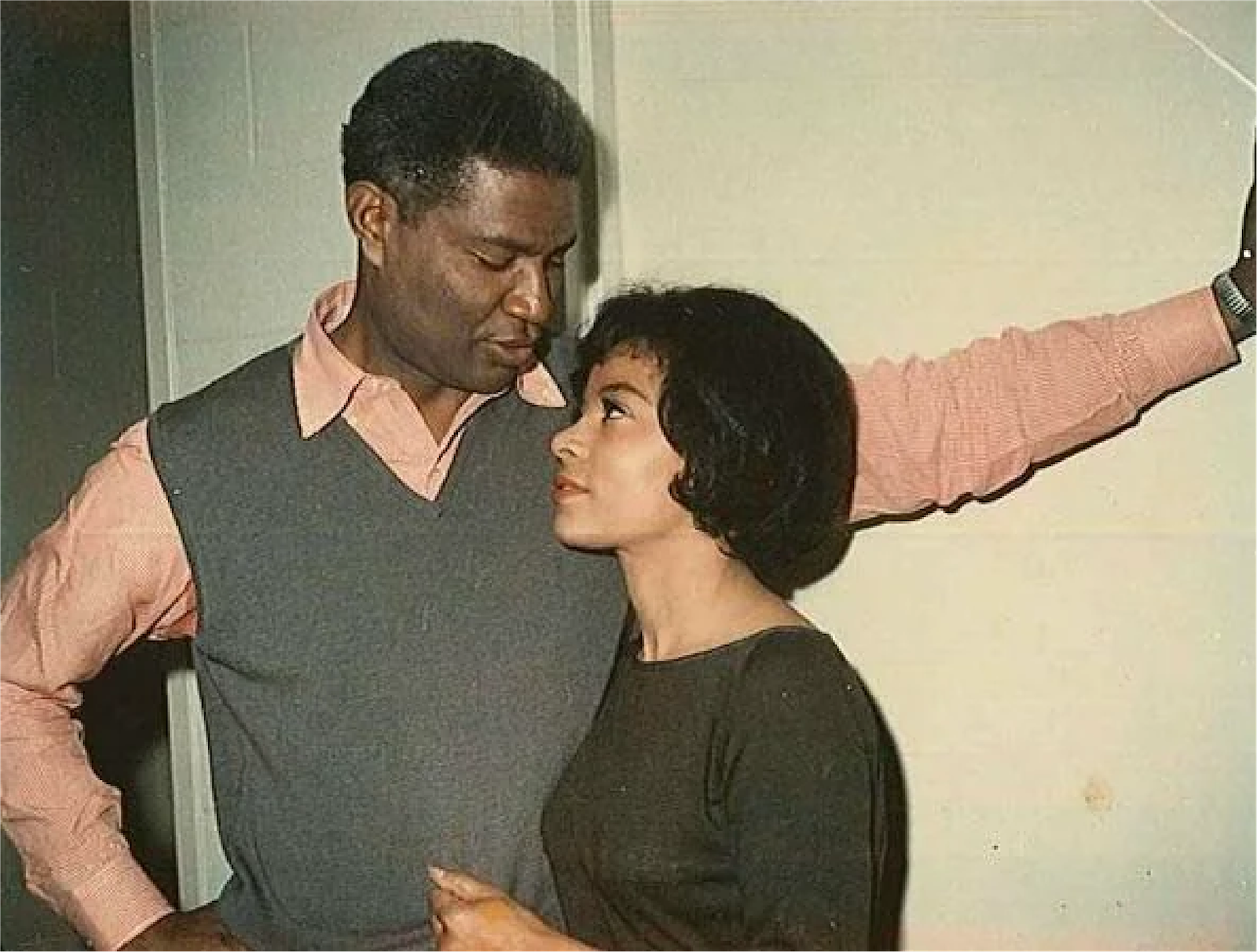

The attraction, when it arrived, is sometimes described in the language of suddenness. A 2014 piece about their family’s tribute efforts repeats an anecdote: Davis pauses to fix his tie during rehearsal, and Dee is, in that instant, captivated—an image of desire arising not from grand seduction but from a small gesture of self-possession. It’s a romantic detail, yes, but it also reads like an actor’s moment: the tie adjustment as a beat, the pause as a choice, the attention as an audience response that changes the scene.

A play that didn’t last—and a bond that did

“Jeb” closed quickly. That fact can be read as indictment of Broadway’s limits or as reminder of theater’s fragility. Either way, it underlines the odd truth at the heart of their origin story: their partnership outlived the very production that created it.

The Washington Post feature emphasizes the tension: the play’s intentions were bold, its commercial life short, but something larger had been set in motion. The article describes the show’s content as a direct confrontation with racism and suggests that even a brief run could shift what playwrights and actors imagined possible. Davis and Dee’s meeting becomes, in that framing, one more consequence of the risk—a private outcome of a public provocation.

Years later, institutional biographies would compress this period into a clean sequence—met in “Jeb,” married in 1948, collaborated for decades. The Kennedy Center, in its profile of the couple, treats their life as a shared artistic legacy, emphasizing their joint stature in American culture. That kind of summary is accurate, but it is also smoothing; it turns a life of negotiation into a timeline of achievements.

The truth is that the years between meeting and marriage were not merely a romantic runway. They were years of building careers in an industry that offered Black actors limited roles and often expected gratitude for scraps. They were also years of learning each other’s ambitions. Two performers with equal talent can become rivals as easily as lovers. That they did not—at least not fatally—was part character, part strategy.

The marriage: A bus to New Jersey and a decision made practical

When Dee and Davis married, the scene was not glamorous. In the Guardian’s account, in December 1948 they took a day off from rehearsals for another play, boarded a bus to New Jersey, and got married. Dee later described the act as almost administrative—like an appointment they finally got around to keeping. This is one of the most striking reported details in their story because it reframes romance as logistics: love expressed through a day off, a bus ride, a courthouse simplicity.

The unadorned nature of the wedding tells you something about how they understood their lives. They were not merely pairing off; they were aligning two working artists in a world that could chew one up, let alone two. Marriage, in this context, could be intimacy, yes—but it could also be mutual reinforcement, a shared household economy, a public signal of seriousness. It could be a kind of shelter.

This is where later storytelling about them often turns hagiographic, portraying their union as pure partnership without friction. But the most credible accounts do not require perfection to make them compelling. They require endurance.

The shared life: Artistry as a long conversation

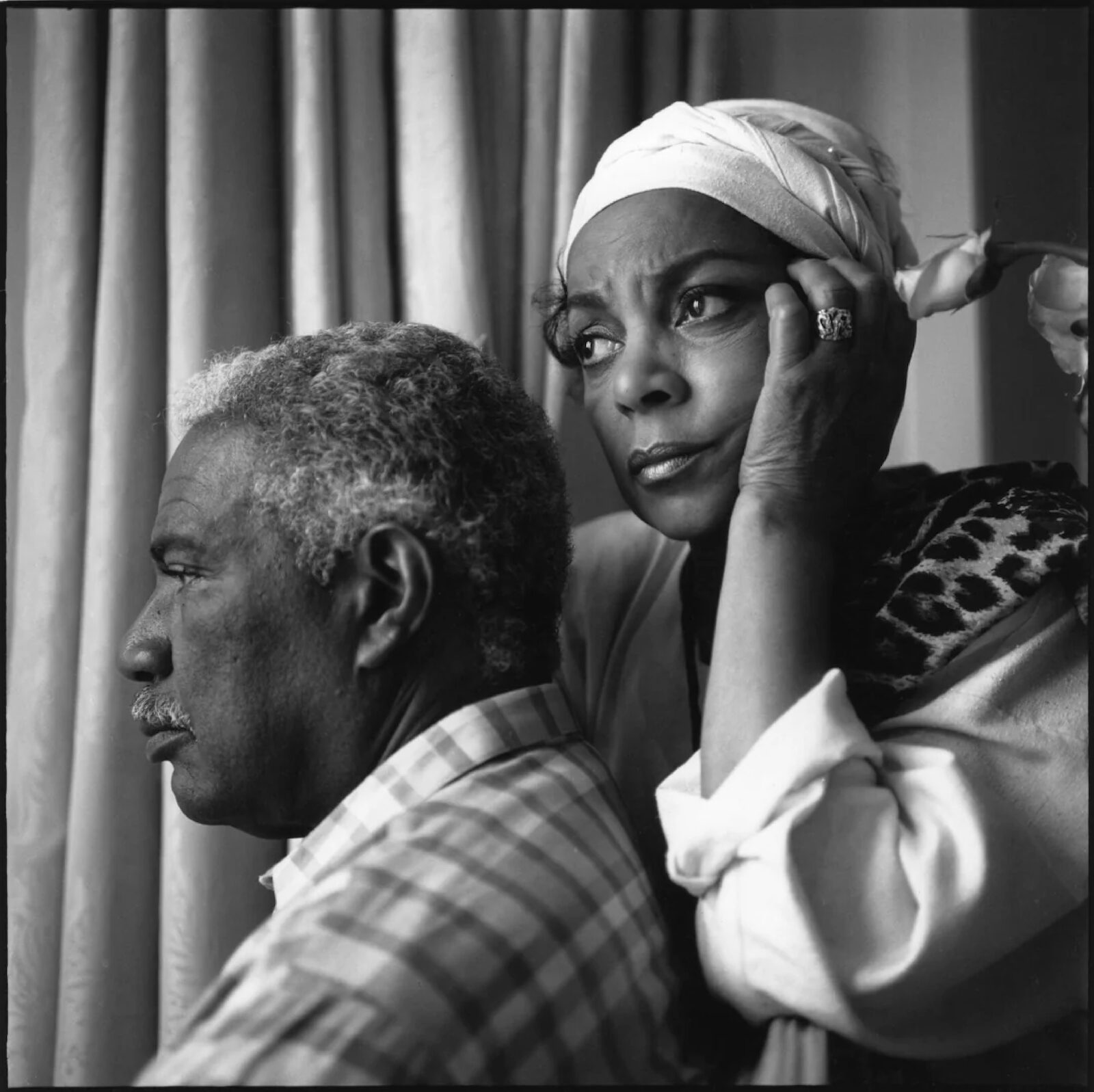

One way to understand Davis and Dee is to view their marriage as a continuous rehearsal—two people refining a scene over decades, rewriting lines, renegotiating power, returning night after night to the same questions: What do we believe? What will we do for money? What will we refuse? What will we risk?

Their careers repeatedly intertwined. The King Institute notes that after marrying in 1948, they wrote and appeared in many stage, film, and television projects and maintained relationships with movement figures including Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr. Their public lives were not separate tracks; they were braided.

That braiding is key to understanding why their origin story still matters. They did not simply meet and marry; they became, over time, a unit of cultural production. When Davis was cast, it reflected on Dee. When Dee accepted a role, it shaped how Davis was seen. When one spoke politically, the other’s silence could be interpreted as agreement. Their partnership created power, but it also created expectation.

The Guardian’s obituary for Davis underscores the “always linked” nature of their names, noting that they performed together and married during a rehearsal period, and that their joint autobiography marked their 50th anniversary. Even in death notices, they are narrated as a pair. That is rare; it is also, in some ways, a constraint.

And yet they appeared to embrace the coupling, leaning into it rather than fleeing it. Not because they lacked individuality, but because they understood what their pairing symbolized to Black audiences and to the wider country: continuity, dignity, a model of Black partnership not defined by tragedy.

The activist life: When fame becomes a tool, not a shield

The request to write about “how they met” cannot be separated from what they did with the life that followed. Their partnership became legible to the public partly because it was not confined to theater lobbies or film sets. It traveled onto picket lines and podiums, into campaigns and memorials.

The King Institute’s documents describing Davis and Dee position them not merely as celebrity supporters but as people who maintained relationships with movement leaders and participated in the moral weather of their time. Their activism was not a phase; it was a parallel career.

This is where their origin in “Jeb” matters again. A play about a Black veteran facing the Klan is not just an early credit; it is a kind of thesis statement. It suggests that from the beginning, their art was in conversation with the country’s violence and its lies. Later, when they used their visibility in civil rights contexts, they were not pivoting; they were continuing.

The Washington Post profile from 2004 frames their activism as inseparable from their artistry—“Their Activism Is No Act”—and situates that activism within a history of risk-taking on stage. That formulation can sound like branding, but it carries an analytic point: for Davis and Dee, the performance and the politics were mutually reinforcing disciplines.

A marriage, revised: The honesty they allowed themselves

The most challenging part of writing about Davis and Dee with journalistic integrity is resisting the temptation to turn them into uncomplicated saints. They were widely admired; they also spoke frankly, at least at certain points, about marriage as a lived reality rather than a poster.

Ebony, reflecting on their “unique marriage,” reports on their discussion of an open marriage and the ways they framed that choice as part of grappling with love’s complexity. Whether a reader views that as brave, troubling, pragmatic, or painful, the point is that the couple themselves declined to present marriage as effortless. They presented it as negotiated.

That candor complicates the origin story in the best way. It suggests that what began in the charged environment of a Broadway rehearsal room did not harden into a single unchanging form. It evolved. They revised it, sometimes in ways audiences did not want to hear. They did not merely sustain a partnership; they redefined it so it could continue.

In contemporary celebrity culture, where “couple goals” imagery sells, such admissions are often punished or ignored. Yet their willingness to speak about imperfection may be part of why their bond retained meaning. It wasn’t just that they stayed together. It was that they had to decide, over and over, what “together” would mean.

The public story versus the private reality

There is an ethical question embedded in any profile of a long marriage: how much can you infer from the public record? How do you honor privacy while telling the truth?

In Davis and Dee’s case, the public record is unusually rich, but it is still partial. Institutional biographies can tell you where they met and when they married. Archival collections can show you programs, clippings, and correspondence. Obituaries can capture the shape of a life. What none of it can fully render is the daily texture: the arguments about money, about ambition, about parenting, about whether to take a role, about whether to speak at an event, about how to remain tender when tired.

Still, you can see certain patterns. One is humor, often deployed as armor and invitation. A recent reflection published in 2025 describes Davis telling the origin story of their partnership with a glinting joke—“I married for money,” he quips—an example of how he could use comedy to disarm the audience before steering toward something more serious. The line is funny precisely because it is obviously not the full explanation, and because it suggests that their bond could handle irony without collapsing.

Another pattern is the way their professional lives kept circling back into each other’s. The Guardian obituary notes they shared billing in numerous stage productions and multiple films, and it emphasizes their parallel careers across media. Working together is not always romantic; for actors, it can be exhausting. But it also means they were repeatedly choosing to make art in each other’s presence, a choice that can either deepen intimacy or destroy it. For them, it seems to have done more of the former than the latter.

Why “Jeb” still matters, and what their meeting tells us now

It can be tempting to treat “how they met” as trivia—something to be recited on anniversaries, an anecdote for social media. But Davis and Dee’s meeting is a useful lens for understanding how Black cultural power was built in mid-century America: not through a single breakthrough, but through networks, institutions, and shared labor.

“Jeb” mattered because it was a Black-centered narrative in a mainstream venue, staged in a period when the country wanted to congratulate itself for winning a war while refusing to confront the domestic terror inflicted on Black citizens. The play’s premise—a Black veteran confronting the Klan—forced audiences to acknowledge that “home” could be another battlefield. That Davis and Dee met in that context suggests that their love story was incubated inside a political contradiction. It also suggests why their later activism did not feel like a separate chapter; it was part of the origin.

The NYPL archive note about programs for “Jeb” is, in its dryness, almost moving. A program is a disposable object, meant to be folded, carried, tossed. To preserve it is to insist that the night mattered. To preserve it in a collection defined by the couple’s shared life is to say: here is where the story became “our” story.

Their marriage, in turn, mattered because it stood as a counter-narrative. In a country invested in depicting Black families as unstable or pathological, Davis and Dee offered a public image of endurance. Yet they also complicated that image by refusing to pretend endurance meant purity. They suggested endurance might mean honest accounting.

The legacy of a shared life: What endures after the curtain

When Ruby Dee died in 2014, and when Davis had died years earlier, the obituaries returned again to the origin point: “Jeb,” Broadway, the meeting. The repetition is not lazy; it is structural. The play is the hinge. It’s where two biographies snap together into one narrative arc.

And the narrative arc, viewed from a distance, is almost impossible not to admire: two artists who did not simply collect accolades but used their visibility as a lever; two performers who insisted that Black life belonged at the center of American storytelling; two partners who made a marriage in public without letting the public fully own it.

If you want the most honest takeaway from reported accounts, it is this: they met because they were working. They stayed connected because they kept working—on art, on politics, on family, on themselves. Their love story is less a lightning bolt than a long practice.

In that sense, the most important detail about how Ossie Davis met Ruby Dee is not the tie adjustment or the first impression or the bus to New Jersey. It is the setting: a rehearsal room where Black artists were trying to tell the truth in a country allergic to it. They recognized something in each other there—talent, yes, but also stamina. They chose, again and again, to build a life that could carry both.

That is not a fairy tale. It is something harder, and rarer: an honest and loving relationship that survived the closing notices.

More great stories

The Man Who Outwrote the Fugitive Slave Law