... to unite “Africa and the Africans, at home and abroad.

... to unite “Africa and the Africans, at home and abroad.

By KOLUMN Magazine

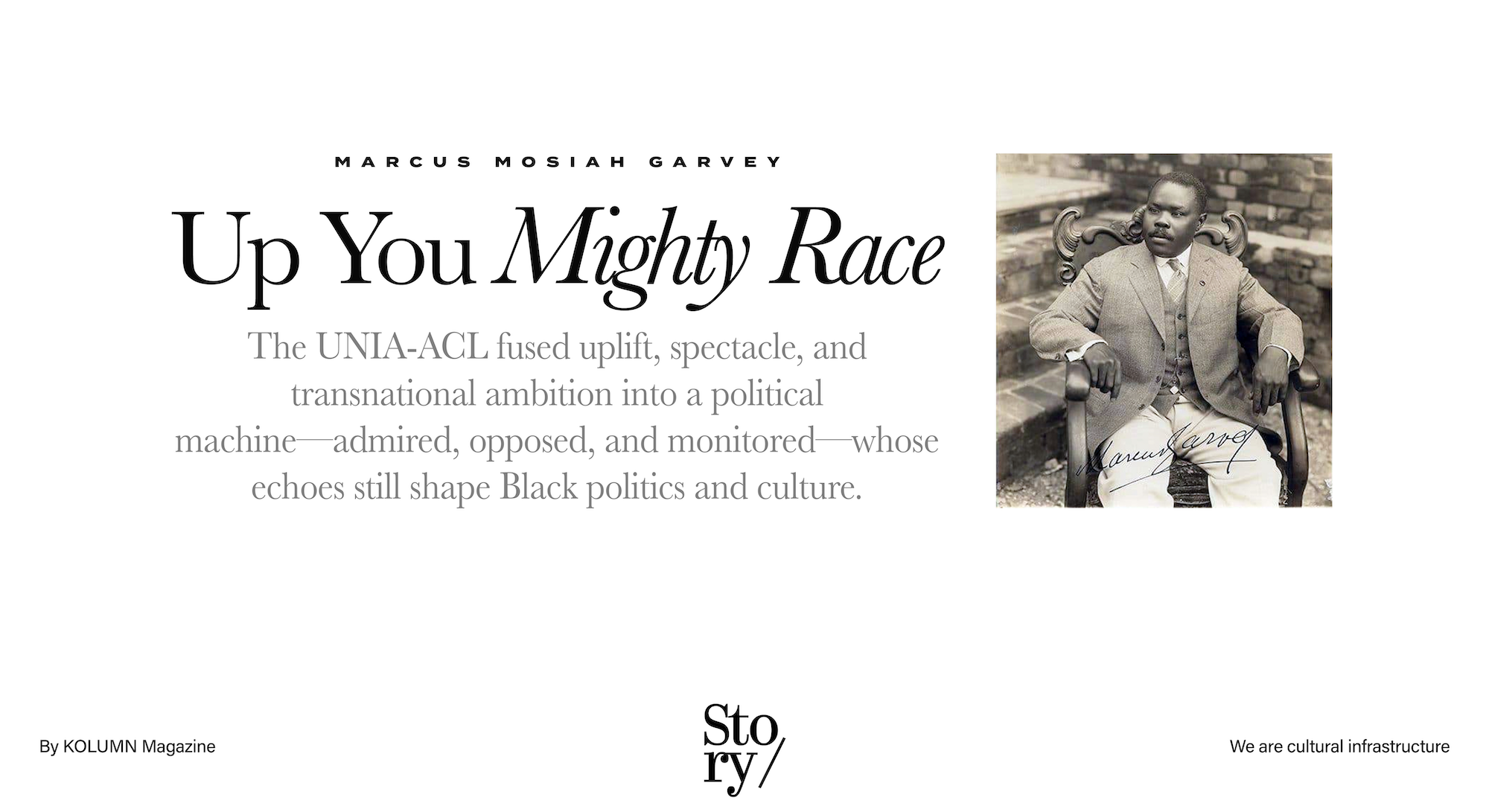

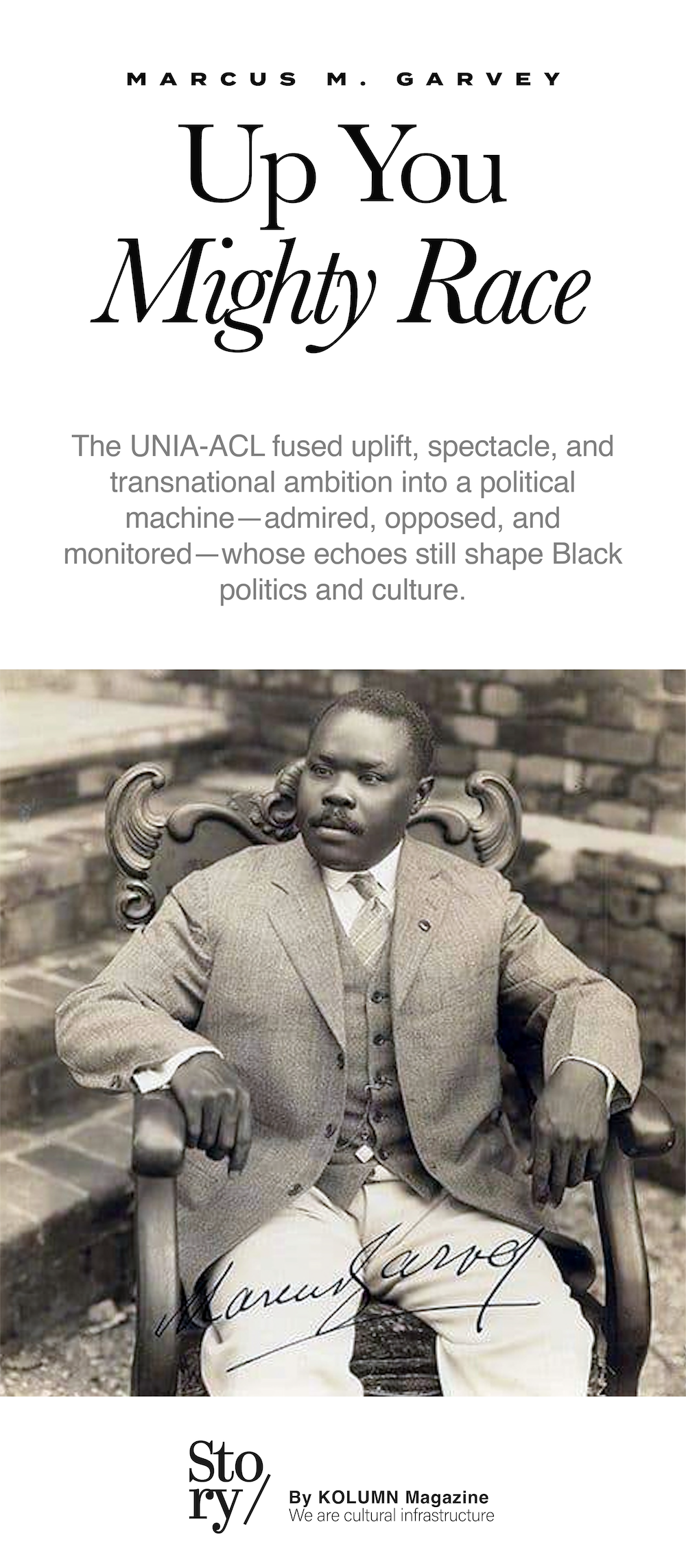

On a summer day in Harlem in the early 1920s, you could feel the Universal Negro Improvement Association and African Communities League before you could fully explain it. You heard it first: the brass of marching bands, the cadence of boots, the call-and-response of a crowd that had come not merely to watch but to participate in a vision. You saw it in the uniforms—Black Cross Nurses in white, an African Legion in military garb—and in the flags and banners that did what speeches alone could not: they made an imagined nation visible. The UNIA-ACL specialized in turning aspiration into choreography. It was not the only Black political project of its era, but it was the one that understood, earlier and more completely than most, that modern mass politics is partly theater—except the stakes were not applause. The stakes were dignity, power, and the right to define the future.

To tell the story of the UNIA-ACL is to enter the engine room of one of the largest mass movements in Black history, a global project that, at its height, claimed branches across the United States and throughout the Caribbean, Central and South America, and parts of Africa, linking dockworkers and domestic workers, preachers and printers, small-town organizers and Harlem strivers into a transnational network. It is also to confront a set of contradictions that still haunt Black politics: the tension between integration and separatism; between symbolic nationhood and practical economics; between charismatic leadership and accountable governance; between solidarity and the temptations of spectacle; between state repression and internal collapse. The UNIA-ACL’s ambition was audacious—to unite “Africa and the Africans, at home and abroad,” and to build institutions sturdy enough to survive the hostility of white supremacy and the skepticism of Black elites. It succeeded, and it failed, and it did both so loudly that a century later the argument about what it meant—and what it warns—has not cooled.

In January 2025, that unfinished argument acquired a new official chapter when President Joe Biden posthumously pardoned Marcus Mosiah Garvey, whose 1923 mail-fraud conviction had long been framed by supporters as politically motivated and by critics as the predictable result of reckless business practices. The pardon did not settle the historical debate, but it underscored a reality that historians have long recognized: Garvey and the UNIA-ACL were not marginal. They were central enough to be watched, prosecuted, ridiculed, feared, imitated, and—eventually—rehabilitated.

What follows is not a monument and not a takedown. It is an attempt to understand how an organization born in Jamaica became a worldwide machine of Black self-definition, what it built, why it fractured, and why its afterlife still shapes politics and culture—often in ways people invoke without realizing the source.

From St. Ann’s Bay to Harlem: The making of a mass organization

The UNIA began in Jamaica in 1914, founded by Marcus Garvey, a printer’s apprentice turned political organizer whose early life and travels—through Central America and England—convinced him that Black people across the diaspora faced linked problems that required linked solutions. The organization’s name was, even then, a declaration of scale: “Universal” was not rhetorical flourish; it was instruction. So was the paired “African Communities League,” a signal that the UNIA’s target was not only civil rights in the Americas but a remade relationship to Africa itself—political, economic, and psychological.

Garvey arrived in the United States in 1916 and, by 1918, inaugurated a New York division that would become the organization’s nerve center. Harlem was not just a neighborhood; it was a stage and a switchboard. The Great Migration had turned Northern cities into laboratories of Black modernity—crowded, exploited, culturally alive—and the post–World War I years intensified both the possibility and the violence. In that environment, the UNIA offered what many people were desperate to find: a coherent story about Black worth, a set of institutions to inhabit that story, and a disciplined aesthetic that made participants feel they were part of something sovereign.

One of the UNIA’s most consequential innovations was media. In August 1918, it launched the Negro World, a weekly newspaper that carried Garvey’s editorials, international news, and a recurring page centered on women readers and writers. The paper traveled widely through the diaspora, and multiple sources describe how colonial authorities sought to ban or suppress it, precisely because it treated Black political imagination as contagious. For the UNIA, the newspaper was not an accessory; it was infrastructure—an early version of what we now call narrative control. It taught readers to see themselves as part of a global majority rather than a beleaguered minority.

The organization also built physical space. In 1919, the UNIA purchased Liberty Hall in Harlem, a building dedicated that July, with space for thousands and a regular cadence of meetings, performances, and ceremonies. Liberty Hall was not merely a venue. It was a parliament of feeling. The weekly gatherings were staged with a kind of liturgy—entrances, anthems, guards of honor—that made the crowd’s belief visible to itself. In a world that insisted Black people had no legitimate claim to sovereignty, the UNIA practiced sovereignty as a ritual until the ritual began to harden into identity.

From the outside, some observers mistook that pageantry for frivolity. From the inside, it was pedagogy. The UNIA taught people how to belong to a nation they could not yet point to on a map.

“Africa for the Africans”: ideology as emotional technology

Garveyism—an elastic set of ideas attached to Garvey’s leadership—was never only a doctrine. It was an emotional technology that made pride into a method. Its signature insistence was that Black people should not measure themselves by white approval, and that collective advancement required institutions, enterprises, and cultural symbols owned and controlled by Black people. Sources that summarize the movement’s scale and reach consistently return to the same core: Black pride, economic independence, Pan-African unity, and a “Back to Africa” orientation that was sometimes literal, sometimes metaphorical, and often both at once.

The “Back to Africa” phrase can mislead modern readers into thinking the UNIA was simply proposing mass emigration. For many supporters, Africa functioned as a political horizon—a promise that Black people’s story did not begin with enslavement and did not end with American caste. Garvey’s genius was to make that horizon feel actionable. The movement offered uniforms to wear, songs to sing, newspapers to read, meetings to attend, shares to purchase, and titles to confer. It made the abstract concrete.

That concreteness took its most famous form in August 1920, when the UNIA convened a major international gathering in New York that drew thousands and culminated in the adoption of the “Declaration of Rights of the Negro Peoples of the World.” In that declaration, the movement asserted a sweeping set of claims about dignity, rights, and self-determination—and it codified symbols that still circulate today. Article 39 designated red, black, and green as the colors of the “Negro race,” cementing what became known as the Pan-African flag in its modern form.

This was politics done as branding, yes—but branding in the service of liberation is still politics. By giving people a flag, the UNIA made a dispersed population feel like a people with a common story. And by pairing symbols with a declaration, it attempted to anchor feeling to principle.

An organization with departments, uniforms, and a global map

What made the UNIA-ACL different from many contemporary movements was its appetite for organizational complexity. It did not want to be a club; it wanted to be a state-in-waiting, complete with auxiliaries that addressed health, discipline, education, and public ceremony.

The Black Cross Nurses, for example, became one of the movement’s most visible arms, promoting health education, hygiene, maternal care, and related forms of community uplift—work that positioned care as part of nation-building rather than private charity. Meanwhile, sources that survey Garveyism’s structure describe an African Legion and other uniformed units that amplified the movement’s militarized aesthetic—an attempt to convey seriousness and readiness in an era when Black vulnerability was a daily fact.

It is tempting, now, to read those uniforms as costume. But for members, they were often an antidote to the everyday humiliations of racial caste. A uniform says you are part of an institution; it says your body belongs not to someone else’s labor market but to your own collective purpose. The UNIA recognized that pride is not a mood; it is a practice. The organization offered practices.

Geographically, the UNIA’s spread was a marvel of the era’s logistics. Accounts of its high point describe divisions across dozens of countries, including heavy presence in the United States and significant chapters throughout the Caribbean and Central America—regions tied together by shipping routes, labor migration, and the seafaring networks that also carried the Negro World. The movement’s globality was not a metaphor; it was a route map.

And that route map mattered. It meant the UNIA could speak to multiple Black experiences at once: Jim Crow in the American South, industrial exploitation in Northern cities, colonial domination in the Caribbean and Africa. It also meant internal tension was inevitable—because what “self-determination” demanded in Harlem could look different in Kingston, Panama, or the Gold Coast.

Still, the UNIA’s sheer organizational reach reshaped what was politically imaginable. If Black people could coordinate parades, conventions, newspapers, and businesses across borders in the early 20th century, then the claim that Black people lacked the capacity for self-rule began to look less like “common sense” and more like propaganda.

The Black Star Line: Economics as spectacle and as risk

The UNIA’s most famous attempt to convert ideology into infrastructure was the Black Star Line, incorporated in 1919 as a shipping company intended to promote commerce among Black communities and, in Garvey’s expansive vision, to help link the diaspora to Africa through trade and transportation.

The idea was brilliant as symbolism. A ship is the most literal reversal of the Middle Passage one can imagine: a vessel owned by Black people, moving by Black intention, connecting ports that had long been connected by empire. It is hard to overstate what that symbol did for recruitment and morale. PBS’s American Experience, in summarizing the project, notes that even as the venture became a “business fiasco,” it remained a powerful propaganda tool and emblem of Black potential.

As a business, however, the Black Star Line was vulnerable. Shipping is capital-intensive, technically complex, and unforgiving of mismanagement. Multiple historical summaries attribute the line’s failure to expensive repairs, corruption, and administrative weakness—problems magnified by the political hostility surrounding Garvey and the UNIA.

The line’s troubles also became a doorway for government scrutiny. Garvey was indicted and then convicted of mail fraud connected to the sale of Black Star Line stock—an outcome that has remained a battleground of interpretation. The Washington Post’s later reporting on the conviction recounts the basics: on June 21, 1923, Garvey was convicted, fined $1,000, and sentenced to five years, while other defendants were acquitted. The National Archives’ overview similarly notes the conviction and describes the intense scrutiny around Garvey, including criticism stemming from his meeting with white supremacists.

For supporters, the Black Star Line was an imperfect but earnest attempt to build a global Black economy, punished by a hostile state that feared its political implications. For critics—including some Black contemporaries—the venture was reckless, and its failure predictable, with investors bearing the cost of Garvey’s grandiosity. Those narratives still compete, in part because both contain elements of truth: the dream was real, and the execution was uneven; the state’s hostility was real, and internal mismanagement was also real.

Conflict inside Black politics: Elites, rivals, and the problem of legitimacy

No mass movement grows without making enemies. Garvey’s enemies came in multiple forms: white officials and agencies that monitored him; mainstream Black leaders who saw him as dangerous or irresponsible; and rivals within the broader ecosystem of Black political thought.

The UNIA’s relationship with “the Black establishment” was especially fraught. Scholars have explored how Black elites—committed to their own forms of racial progress—often opposed Garveyism, viewing it as demagoguery, a threat to hard-won respectability, or a political dead end. The battle was not only ideological; it was also about who had the right to speak for Black people. Garvey’s claim to represent “the Negro peoples of the world” challenged the authority of organizations rooted in a narrower class base.

Garvey also made decisions that intensified opposition. One of the most controversial was his 1922 meeting with Ku Klux Klan leaders—an episode documented in multiple historical summaries as a catalyst for backlash and for campaigns to remove him from leadership. Garvey’s reasoning, by many accounts, was bound up with his separatist belief that integration was a trap and that even white supremacists, in their desire for separation, could be treated as proof that races could not meaningfully coexist within the same national project. But to many Black contemporaries, the act was unforgivable: negotiating with an organization built on terror looked less like strategy and more like capitulation.

This is one of the places where journalistic clarity matters. Garvey was not simply “flirtatious” with extremism; he met with leaders of a violent white supremacist organization, and that meeting strengthened opposition to him, including among Black leaders. Any honest appraisal has to hold that fact alongside the movement’s genuine achievements.

At the same time, it is also true that Garvey operated in an environment where the state routinely criminalized Black organizing, and where surveillance could blur into sabotage. Archival projects and historical overviews describe intense government attention directed at Garvey and the UNIA, framing him simultaneously as a movement leader and as a perceived threat. The line between “investigation” and political containment was often thin in early 20th-century America, especially when Black movements challenged economic and national norms.

The result was a perfect storm: a movement led by a charismatic figure whose weaknesses were visible; surrounded by enemies eager to magnify those weaknesses; and sustained by followers who needed the movement to be true even when its institutions faltered.

Women in the UNIA: Labor, leadership, and the politics of visibility

The UNIA’s public imagery often centered male leadership—Garvey in plumed regalia, male officers with titles, an African Legion projecting disciplined masculinity. But the movement’s durability depended heavily on women, as organizers, writers, administrators, and symbols of respectability and care.

The Negro World, for instance, is widely described as carrying a page devoted to women readers and writers, reflecting both the organization’s recognition of women’s centrality and the gendered expectations of the era. The Black Cross Nurses made women’s public labor unmistakable, framing health work as nation work.

Women also played complicated roles in Garvey’s personal and political story, and modern retellings continue to explore how women around him shaped the movement—sometimes protecting him, sometimes challenging him, often doing the unglamorous work that made the machine run. If the UNIA was, among other things, a rehearsal for Black sovereignty, then women were among its key choreographers—even when they did not always receive equal credit.

This matters for legacy. Too often, Garveyism is remembered as a masculine politics of uniforms and ships. But part of what made the UNIA a true mass movement was that it provided multiple entry points for participation. It was not only a lecture circuit; it was a social world.

The state responds: Surveillance, prosecution, deportation

A movement that claims nationhood inside a nation will eventually test the limits of what the state tolerates. The UNIA’s rise coincided with an era of intensified federal policing and political repression, and Garvey became a prime target.

By the early 1920s, Garvey faced mounting scrutiny and internal dissent. PBS notes that as the Black Star Line neared financial collapse, Garvey suspended the company shortly after a 1922 indictment tied to Black Star Line stock sales. The National Archives recounts that he was convicted and sent to federal prison, while also noting the broader pressures—negative press, investigations, and public criticism—that shaped his reputation.

Washington Post reporting on the later efforts to win clemency provides additional detail: Garvey served nearly three years before President Calvin Coolidge commuted his sentence, after which Garvey was deported to Jamaica. Deportation was not just punishment; it was a political strategy, removing a movement leader from the country where the organization’s base had become strongest.

The question of whether the prosecution was “political” is not a yes/no proposition so much as a matter of emphasis. It is plausible—and many advocates have argued—that Garvey was pursued with special zeal because of his influence, not simply because of business misconduct. (The Guardian) It is also plausible—and historically supported—that the Black Star Line’s promotional practices and administrative weaknesses created genuine legal exposure. The point is that the state did not have to invent problems; it only had to exploit them.

And exploit them it did. After Garvey’s removal, the UNIA’s coherence weakened. Charismatic movements can survive scandal if their institutions are sturdy. The UNIA’s institutions were ambitious, but many were also financially fragile, dependent on trust, momentum, and the belief that the dream was still ahead.

Decline is not disappearance: How an idea outlives an institution

By the mid-to-late 1920s, the UNIA had lost much of its peak power, and the Black Star Line had already collapsed. Yet decline is not the same as erasure. The most important political inventions rarely vanish; they migrate.

Garveyism migrated into culture. The red-black-green flag, codified in 1920, became a recurring symbol in later Black political movements and cultural rituals, a piece of visual language that continued to declare unity and pride even when the UNIA’s own organizational strength waned. The UNIA’s insistence on Black self-definition also shaped later nationalist thought in the United States and beyond, influencing the rhetorical worlds that produced mid-century Black radicalism.

Garveyism migrated into politics abroad. The symbolism of the Black Star Line echoes in the iconography of later Pan-African projects, and popular historical summaries frequently note how Garvey’s language and aesthetics traveled into independence-era imaginations—even when the UNIA itself did not “create” those states. The point is not to claim direct organizational causality; it is to recognize that Garvey helped normalize the idea that Black people could and should think in the scale of nations and continents.

Garveyism migrated into argument. The movement’s most persistent legacy may be the debate it forced: is Black liberation best pursued through integration into existing states, or through building parallel institutions that reduce dependence on hostile systems? The UNIA did not invent this question, but it dramatized it so effectively that the question became unavoidable.

Even in contemporary journalism about Garvey’s legacy, that debate remains alive. The Guardian’s account of the decades-long pardon campaign frames Garvey as a revolutionary figure whose conviction was seen by supporters as a mechanism to suppress a mass movement. Word In Black’s coverage of the 2025 pardon situates it as a “reach back” into the past that affirms Garvey’s place in civil rights genealogy, emphasizing the symbolic weight of state recognition after a century of dispute.

The 2025 pardon: What it changes, what it can’t

A pardon is not a time machine. It does not resurrect investors who lost money or erase harm caused by poor decisions. It does not rewrite the internal conflicts that tore at the movement. What it does do is signal how a state chooses to narrate its own past.

On January 19, 2025, the Department of Justice’s published list of pardons granted by President Biden includes Marcus Mosiah Garvey, referencing his 1923 conviction in the Southern District of New York for using the mails in a scheme to defraud. PBS NewsHour’s report on the pardon describes Garvey as a Black nationalist whose ideas influenced later civil rights leaders. (PBS) The NAACP Legal Defense Fund publicly praised the clemency announcement, placing Garvey among a set of people whose cases, in their view, represented the “power” of clemency to address injustice.

For Garvey’s advocates—including family members and legal supporters—this was vindication and restoration. For others, the pardon is more complicated: it can read as absolution for a movement whose economic ventures caused real financial pain and whose leader engaged in morally compromised alliances.

The more precise way to interpret the pardon is narrower. It is a statement that, whatever Garvey did wrong, the conviction and punishment are no longer what the U.S. government wants to emphasize as his defining story. That shift matters because Garvey’s impact is not abstract. The UNIA-ACL shaped the vocabulary of Black pride and transnational unity in ways that ripple through modern identity and politics.

What the UNIA-ACL built that still matters

The UNIA-ACL’s most enduring contribution may be its demonstration that mass politics can be built from below, across borders, by people who are routinely told they have no right to think at scale.

It built a communications network. The Negro World helped make diaspora a lived reality, providing regular proof that Black life was not provincial but global.

It built institutions of gathering. Liberty Hall and the UNIA’s dense presence in Harlem turned a neighborhood into a headquarters for a worldwide imagination.

It built a repertoire of political aesthetics. Flags, uniforms, parades, titles, anthems—these were not superficial. They were tools that trained participants to feel like citizens rather than petitioners.

It built an argument about economics. The Black Star Line’s failure does not erase the underlying claim: that freedom without economic capacity is vulnerable. The UNIA tried—imperfectly—to build that capacity, and the attempt itself changed what many supporters believed was possible.

And it built a warning. The same machinery that can mobilize millions can also magnify a leader’s flaws. Charisma can become a substitute for governance. Symbolism can outpace infrastructure. The UNIA’s story is, in that sense, both inspiration and caution.

More great stories

The Gospel of the Hill