A lie told by a white landowner to a Black man, a scam disguised as metaphysics and a rigged bargain dressed up as providence.

A lie told by a white landowner to a Black man, a scam disguised as metaphysics and a rigged bargain dressed up as providence.

By KOLUMN Magazine

It is one of Toni Morrison’s slyest insults—delivered with a storyteller’s smile and a theologian’s knife—that the Black neighborhood in Sula is called “the Bottom” even though it sits above the town, perched on a hill. The name is not geography but contract: a lie told by a white landowner to a Black man, a scam disguised as metaphysics, a rigged bargain dressed up as providence. The “bottom of heaven,” the farmer claims, is better than the valley. The result is a community built on altitude and humiliation at once, a place forever translating someone else’s joke into its own survival.

From the first pages, Morrison signals what she will do in this novel and in her career: she will take the language that has been used against Black people—its myths, its euphemisms, its “common sense”—and make it confess. She will not write the Black experience as a sociological exhibit for outsiders. She will write it as a full weather system: funny, cruel, tender, superstitious, erotic, exhausted, holy. Sula, published in 1973, is often summarized as the story of two friends, Sula Peace and Nel Wright, who grow up together in that hillside community and then grow apart. That description is true, but it is also small. Morrison’s real subject is what friendship costs in a world that demands allegiance to rules that were never made for you; what it means to be legible to your community; what it means to be loved without being owned; and what happens when a woman insists on becoming herself even if “herself” has no approved shape.

When Morrison won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1993, the Swedish Academy praised the force of her language and her ability to give life to a part of American reality many had ignored. Morrison was born Chloe Anthony Wofford in Lorain, Ohio, in 1931, raised in a working-class family that carried oral tradition as both pleasure and armor. She studied at Howard University and Cornell University, taught, edited, and eventually became a defining voice not only as a novelist but as a shaper of American letters through her work in publishing. Long before the Nobel, long before the Pulitzer, Sula arrived as a kind of provocation: not yet the most famous Morrison novel, but arguably one of her most uncompromising.

To write about Sula as a book is to write about a period in the United States that seemed determined to punish complexity. The novel appears after the legislative victories of the civil rights movement but amid the violent backlash that followed them; after the assassinations; in the wake of Vietnam; while feminism’s mainstream narratives often treated Black women as an afterthought or an exception. Morrison’s second novel refuses to reduce Black life to uplift or pathology. It refuses to turn women into symbols of either purity or ruin. It refuses, perhaps most scandalously, to reassure the reader that moral accounting will be neat.

That refusal is part of the book’s history, part of its significance, and part of why it keeps being rediscovered—by scholars, by artists, by filmmakers, by people who come to it in high school and then return in middle age and find a different book waiting.

Morrison before Sula: The editor as architect, the novelist as insurgent

Morrison published The Bluest Eye in 1970, a debut that announced not only a new storyteller but a new ethic of attention: the insistence that Black interior life, especially Black girlhood, was not a niche subject but a central American story. In the years around Sula, she was also building a career as an editor—work that shaped the landscape in which Black writers could be read, marketed, preserved, and argued with.

It is tempting to separate Morrison’s “writer self” from her “editor self,” as if one created art and the other managed logistics. But the Atlantic’s reporting on Morrison’s publishing career frames her editorial work as a structural intervention—helping to assemble a canon and expand what mainstream American publishing would treat as necessary. That matters for Sula, because the novel is not only a story about a community; it is also, quietly, a story about who controls narrative authority. Who gets to define what a “good woman” is. Who gets to define what a “good Black community” looks like. Who gets to decide what counts as tragedy.

Morrison knew those decisions were often made far away from the neighborhoods they affected. In her fiction, she drags those decisions back home and makes everyone live with them.

The Bottom: A place built from irony, memory, and stolen land

Morrison sets Sula in Medallion, Ohio, in a Black community called the Bottom. The place is fictional, but it carries the grain of real Great Migration towns and the layered class structures within Black America itself. Scholars and guides note Morrison’s use of the Bottom as an edge community—near the white town, subject to its economic decisions, yet culturally distinct, governed by its own rituals and hierarchies.

The novel opens with the news that the Bottom is being destroyed—bulldozed, effectively, to make room for development. The destruction is not merely plot. It is a historical fact of American urban planning and “renewal”: Black neighborhoods razed for highways, hospitals, university expansions, golf courses—projects marketed as progress. Morrison makes that erasure the book’s overture, so that every memory that follows is already haunted by the knowledge that the place will not survive intact.

This structure changes how the reader experiences time. You are not simply watching events unfold; you are watching an archive being assembled against demolition. Morrison’s chapters move across decades, stitching personal lives to national ones. A war returns a man to town with his mind shattered. A marriage reorganizes a girl’s identity. A woman’s sexual independence becomes a civic crisis. A winter turns a community’s resentments into a kind of theology.

Sula Peace and Nel Wright: An intimacy that doesn’t behave

Nel Wright and Sula Peace meet as girls. Their friendship is not sentimental; it is adhesive. They recognize in each other a kind of relief: the possibility of being seen without being corrected. Their bond forms in contrast to the maternal legacies that shape them. Nel’s household teaches respectability and containment; Sula’s family home is stranger, looser, crowded with “strays” and governed by the charismatic, terrifying presence of her grandmother, Eva Peace. (If Morrison wanted to prove that domestic space can be epic space, Eva’s house is exhibit A.)

Their friendship is also, crucially, a space where identity can be rehearsed. In the Bottom, where women’s bodies are policed and men’s failures are often romanticized as fate, friendship becomes a laboratory for selfhood. That’s part of why the relationship between Nel and Sula has generated so much Black feminist criticism and argument: it refuses easy classification. It is neither simply sisterhood nor simply rivalry nor simply a substitute romance. It is a central human relationship with the stakes and volatility of any love story, without the template of conventional courtship.

By the time the women reach adulthood, the town wants Nel to be one kind of woman and Sula to be another. Nel marries, enters respectability, becomes legible. Sula leaves and returns years later with the aura of someone who will not apologize for the life she has lived. The community reads her as contamination.

Morrison does not tell you that the community is wrong to fear Sula. She also does not tell you that the community is right. She tells you, instead, that communities often require a scapegoat to keep their own contradictions from surfacing—and that women like Sula are unusually useful for that purpose.

Shadrack and the invention of ritual: When trauma becomes civic tradition

One of Morrison’s most unsettling gifts in Sula is the character Shadrack, a veteran who returns from World War I traumatized, disoriented, struggling to contain the unpredictability of death. He responds by inventing a holiday: National Suicide Day, a single day when death can be acknowledged, named, and therefore, perhaps, controlled.

That plot line can be read as dark comedy, or as psychological case study, or as folklore. It can also be read as Morrison’s theory of how communities metabolize catastrophe: by turning the unbearable into something repeatable. A ritual is not a cure, but it is a container. The Bottom, which will later use Sula as another kind of container for its anxieties, accepts Shadrack’s holiday into its myth system.

This is Morrison’s realism at its most distinctive: she is not interested in whether something is “plausible” by middle-class standards. She is interested in whether it is true to how humans, under pressure, build meaning. The ritual is absurd. It is also, in a town living under economic and racial constraint, a kind of grim pragmatism.

The “outlaw woman” and the town’s need for order

Morrison has described her fascination with outlaw women—women who escape the “rule” of men, women who treat domestic scripts as optional. In one widely circulated discussion of Sula’s origins and aims, Morrison frames the novel as an exploration of what such an escape does not only to the woman who escapes, but to the community that must interpret her.

Sula is not written as a feminist saint. She can be selfish, reckless, cruel. She can also be honest in a way the town cannot tolerate. She refuses to perform shame, and that refusal is treated as violence. The Bottom’s moral economy depends on visible penitence: the wife who stays, the mother who sacrifices, the girl who does not “invite trouble.” Sula declines those roles, and the community responds as if she has attacked the town’s religion.

One of the most revealing dynamics in the novel is how Sula’s presence temporarily “improves” the community. People behave better, love their spouses harder, parent their children with more urgency—because they have a villain to organize themselves against. Morrison is anatomizing a social phenomenon that remains familiar: the way moral consensus is often manufactured through shared condemnation.

That mechanism is not limited to fiction. It is one reason Sula continues to matter as a cultural document: it reads like a psychological profile of respectability politics, long before the term became common currency.

Style as politics: How Morrison makes a world without the “white gaze”

Morrison’s broader literary philosophy—articulated across interviews and essays—often circles the idea that Black writers should not have to position whiteness as the default audience. The Root has described Morrison as a writer who refused to “privilege” white readers in her work, insisting instead on Black-centered language, context, and moral authority.

Sula embodies that insistence formally. Morrison does not pause to translate the Bottom for outsiders. She expects the reader to learn the town’s logic the way you learn any real place: by listening, by making mistakes, by earning fluency. The result is that the book does not feel like an explanation. It feels like immersion.

This is not simply aesthetic. It is political. When a book refuses to explain itself to power, it changes the relationship between storyteller and audience. It also changes what kinds of characters can exist on the page. Sula can be “dangerously female” without being forced into a corrective narrative designed to reassure a mainstream moral order.

Early reception: Praised, misread, and argued with

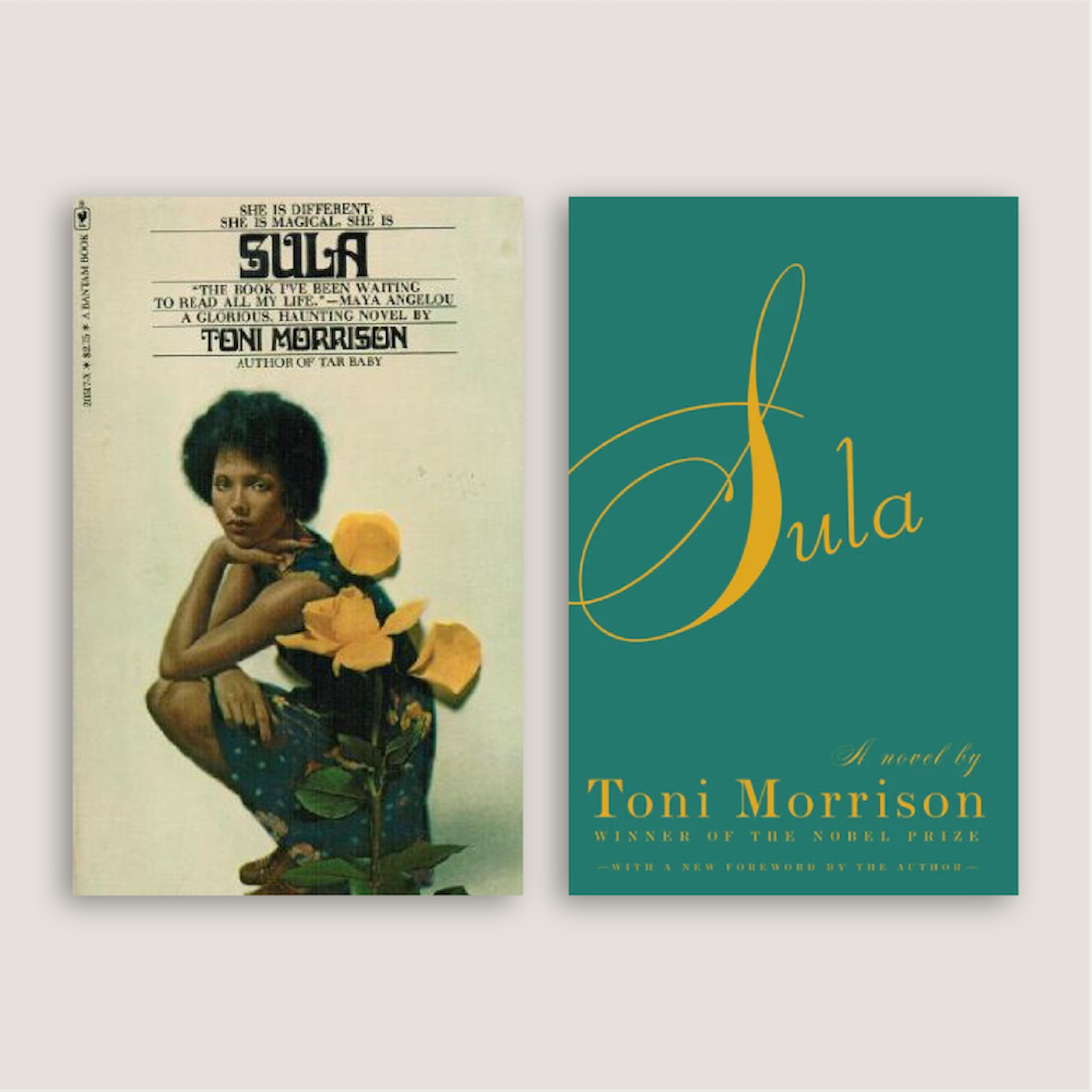

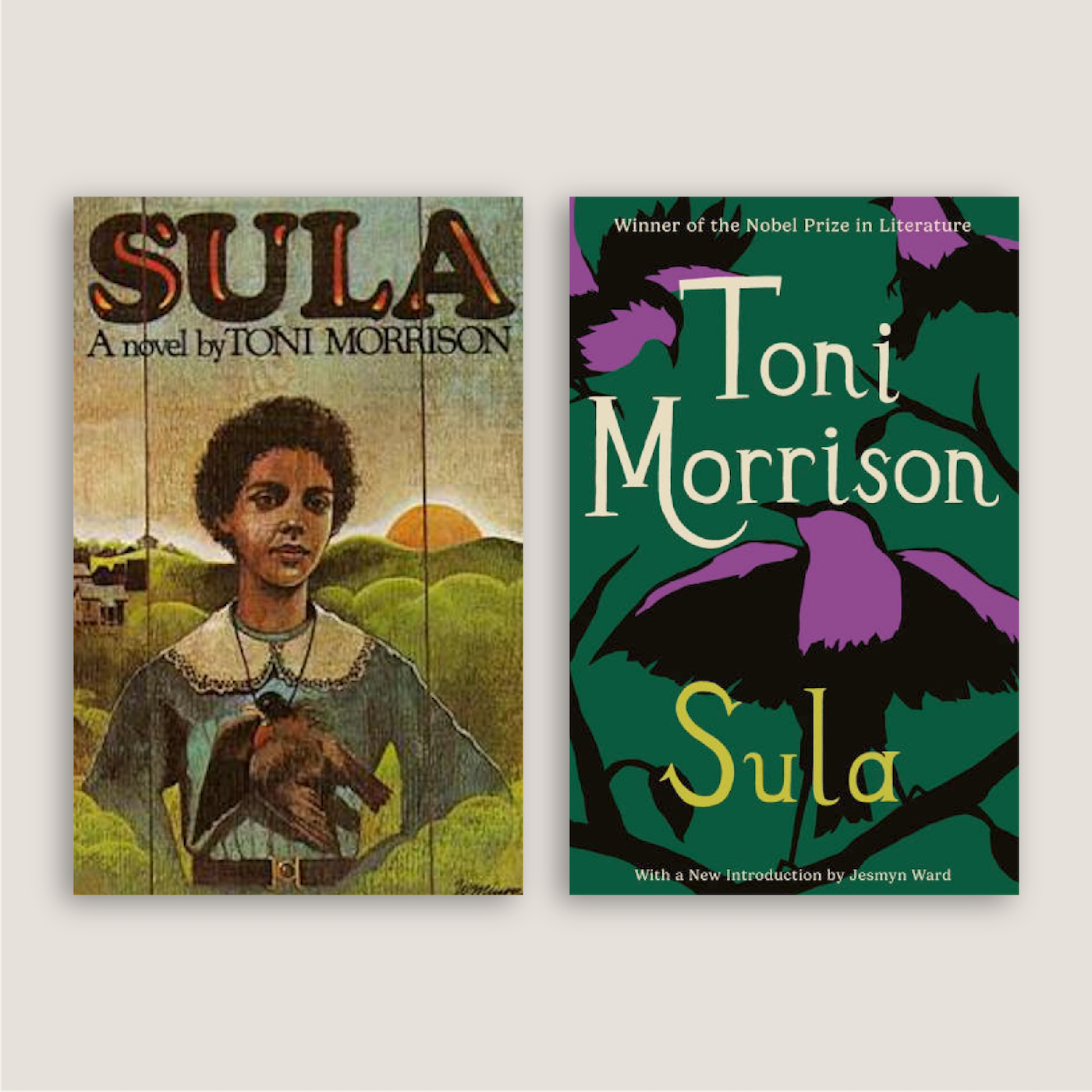

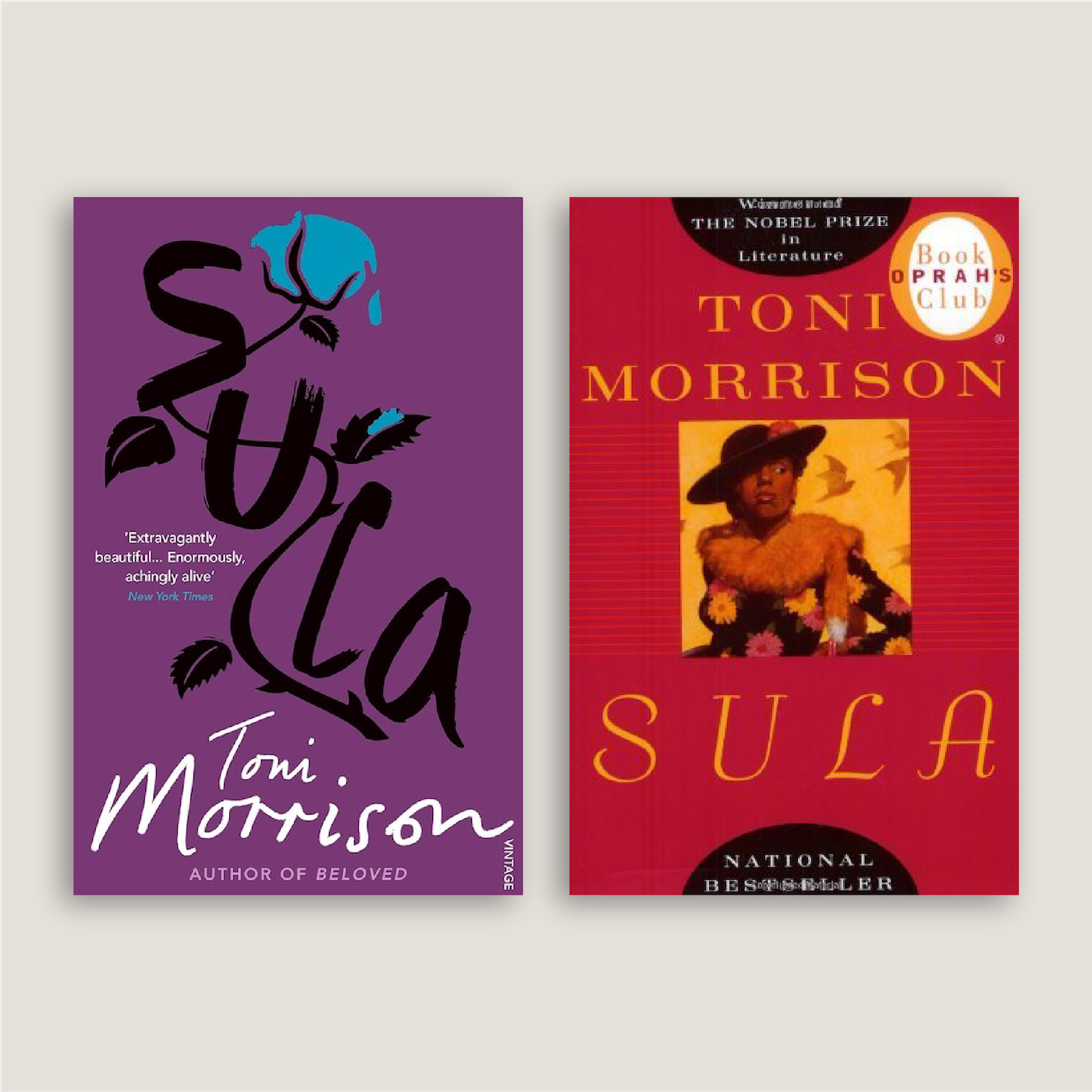

When Sula was published, it received significant attention, including in mainstream outlets. Documentation of the novel’s reception history points to a generally positive early response, including a prominent New York Times review by Sara Blackburn in late 1973.

But the more interesting part of Sula’s reception is not whether critics liked it. It is how often the book has been treated as an argument rather than a story—as if Morrison had smuggled a debate about gender and freedom into the shape of a novel. A Washington Post retrospective on Morrison’s work emphasizes how Sula can be read as, first and foremost, a “mere” novel—funny, humane, rich in dialogue and character—while still carrying political voltage. That tension has followed the book ever since: readers who want Morrison to preach are frustrated; readers who want her to entertain are startled; readers who want her to resolve moral questions are denied.

Morrison’s refusal to settle the case is precisely what makes Sula useful to generations of critics, especially Black feminist critics who recognized that ambiguity itself can be a form of resistance.

Why Sula became foundational for Black feminist literary criticism

In the decades after publication, Sula became central to the development of Black feminist literary criticism, in part because it demanded a language for reading relationships between Black women that were not reducible to stereotypes. Scholarly and critical histories often cite Barbara Smith’s influential essay “Toward a Black Feminist Criticism” and subsequent debates as part of the intellectual ecosystem that formed around the novel.

What made Sula such fertile ground is that it does not offer the conventional feminist arc in which liberation is clearly good, patriarchy is clearly bad, and community is either a villain or a refuge. Morrison shows community as both: a net and a noose. She shows independence as both: ecstatic and isolating. She shows friendship as both: salvation and wound.

This is the book’s hard genius: it is not “about” freedom; it is structured like freedom—messy, consequential, resistant to summary.

The book’s central moral question: What is a free woman for?

If you want a single question that haunts the novel, it is this: what is a free woman for? The town has answers. A woman is for stability. A woman is for children. A woman is for the careful management of public perception. A woman is for absorbing male chaos. A woman is for being judged.

Sula proposes a different answer: a woman might be for herself. That proposition is not presented as a slogan; it is presented as a problem. Morrison understands that “for herself” is not a stable category in a world built to punish autonomy—especially Black female autonomy, which has historically been treated as a threat to both racial order and gender order.

This is why the novel’s erotic and domestic choices generate such heat. Sula’s sexuality is not written as romance; it is written as appetite, experimentation, sometimes carelessness. For the Bottom, that is not merely personal behavior; it is public disruption.

The price she pays is social exile. The price the community pays is moral stagnation, the slow conversion of complexity into gossip.

Fashion, visibility, and the body as narrative

A striking recent Guardian essay about Morrison’s use of clothing and fashion notes that characters like Sula signal autonomy through style—returning home in outfits that command attention, using appearance as both armor and assertion. Morrison’s interest in the body—how it is read, policed, desired, punished—runs through her work, but Sula is an early and potent example. The town reads Sula’s body as a text it can interpret without her consent. That reading becomes a form of control.

The Guardian piece is useful not because it reduces Morrison to “fashion,” but because it shows how Morrison used material details to render psychological states. The cloth is never just cloth. It’s identity management. It’s rebellion. It’s mourning. It’s longing.

Toni Morrison in public life: The moral authority of a novelist

After Morrison’s death in 2019, critics and writers returned again to the idea that she did not merely write novels—she reshaped the moral possibilities of American literature. The Washington Post argued that Morrison “remade” American literature and pressed readers to resist racism’s endurance, situating her not only as an artist but as an intellectual force. Time’s obituary framed her as a writer who chronicled Black American experience with unmatched force, noting her Nobel, her Pulitzer, and her long influence across genres.

Those tributes can feel ceremonial, but they point to a real phenomenon: Morrison became, in American culture, a kind of secular elder, a public mind. That public role often risks flattening the work into “important messages.” Sula resists that flattening. It remains too weird, too funny, too ferocious, too intimate to behave like a monument.

And that is part of its value.

Sula and the ongoing reinvention of the Black woman heroine

Ebony, in an essay about the evolution of Black women protagonists in contemporary fiction, uses Sula as a touchstone—placing Morrison’s heroine in conversation with later novels and later cultural expectations about what a “heroine” is allowed to do. The framing is instructive: Sula is not simply a character study; it is a template that writers either inherit, resist, or rewrite. Morrison made it harder for American fiction to pretend that Black women’s inner lives were secondary.

That legacy is visible not only in literary fiction but in popular culture. Pitchfork’s coverage of Jamila Woods’s song inspired by Sula underscores the novel’s afterlife as personal scripture—an engine for self-definition, especially around gender, love, and constraint. When musicians and poets return to Sula, they are often returning not to plot but to permission: the permission to be complicated without requesting absolution.

Adaptation and the marketplace: What it means that Hollywood wants Sula

In 2022, The Root reported that HBO was developing a limited series adaptation of Sula. The news is easy to treat as entertainment-industry trivia, but it raises a deeper question about Morrison’s place in the contemporary cultural marketplace: what happens when a novel built from interiority, ambiguity, and community rumor is translated into a visual medium that often demands clearer heroes and villains?

Adaptations can renew a book’s audience, but they can also domesticate its danger. Sula’s danger is not sex or scandal; it is the book’s refusal to tell you what to think about its central woman. The risk of adaptation is that the story becomes a verdict.

The opportunity is that the Bottom—its humor, its grief, its rituals—could reach viewers who have never encountered Morrison’s language. If the adaptation is brave enough to preserve uncertainty, it might also preserve what Morrison was actually doing: inviting the audience into moral labor.

KOLUMN Magazine, Morrison, and the Black archive

KOLUMN Magazine’s own coverage has treated Morrison not only as a novelist but as a keeper of Black interior history—someone whose work can be used as a lens for other art forms and archives. A recent KOLUMN feature on photographer James Van Der Zee notes Morrison’s connection to his work (including her presence in a reissued edition’s framing materials) and argues that Morrison’s broader project is about how the past inhabits the living—how memory becomes inheritance.

KOLUMN has also circulated Morrison’s reflections on the formative image behind The Bluest Eye—the remembered confession of a Black girl praying for blue eyes—using that anecdote to foreground Morrison’s method: starting with interior life, then revealing the historical violence that shaped it. Even when KOLUMN is not writing about Sula directly, it is treating Morrison as an interpretive key: a way to talk about Black visual culture, Black self-regard, and the archive of feeling that formal history often refuses to record.

That orientation is consistent with what Sula does. The Bottom is not a backdrop. It is an archive—of rumor, of injury, of endurance, of desire—and Morrison writes it as such.

What Sula teaches, fifty-plus years on

There is a temptation, especially in anniversary years, to describe canonical books as if they have graduated into harmlessness. We praise them as “timeless” and thereby excuse ourselves from their demands. Sula has not become harmless. It still asks the reader to confront a set of questions that remain culturally live:

What do communities do with women who do not center men? What do communities do with women who do not perform shame? What do we call freedom when it harms others, and what do we call duty when it harms the self? How much of what we call “morality” is simply fear organized into etiquette?

The novel also remains formally instructive. Morrison’s narrative method—choral, shifting, intimate with minor characters—refuses the hierarchy that many American novels inherit, where only a few lives are treated as complex. In Sula, everyone has a private weather. Everyone’s choices are shaped by history whether they acknowledge it or not.

In a culture that increasingly rewards instant takes, Morrison’s patience feels like a rebuke. She does not rush to interpretation. She lets contradiction stand long enough for the reader to recognize it as human.

Morrison’s Nobel biography emphasizes her dual identity as novelist and critic—someone who specialized in African-American literature while also reshaping it. Britannica describes her as one of the greatest contemporary American novelists, recognized for examining Black experience—particularly Black female experience—with luminous prose. Those are big claims, but Sula is one of the clearest pieces of evidence.

The novel insists that Black women are not supporting characters in the American story. It insists that a Black community is not a monolith. It insists that love between women—whether friendship, rivalry, kinship—can be the engine of tragedy and revelation. It insists, too, that moral clarity is often a luxury purchased with someone else’s silence.

If Morrison is, as so many obituaries claimed, a conscience of American literature, Sula shows how she constructed that conscience: not by lecturing, but by staging. She builds a town, gives it rules, introduces an outlaw, and watches what everyone becomes in response.

And then, because she is also Toni Morrison, she ends by reminding us that the story we thought was about Sula might, in fact, be about Nel—the respectable one, the socially approved one—finally realizing what she lost, and what she never allowed herself to name.

That final recognition is part of why Sula endures. It does not merely celebrate rebellion; it interrogates the costs of compliance. It does not simply condemn community; it shows why community feels necessary. It does not resolve grief; it gives grief language.

In the end, the life of Sula—its publication in 1973, its evolving critical reputation, its role in Black feminist theory, its reappearances in music and media—mirrors the life of Toni Morrison herself: a career defined by the refusal to reduce Black life to something easy to consume.

The Bottom is gone, at least in the novel’s frame. But Morrison’s art is that you can still hear it: the gossip, the laughter, the warnings, the prayers, the unspoken bargains. A book can be a demolished neighborhood rebuilt in language. A novel can be a town’s afterlife.

That is what Sula is. And that is why it still matters.

More great stories

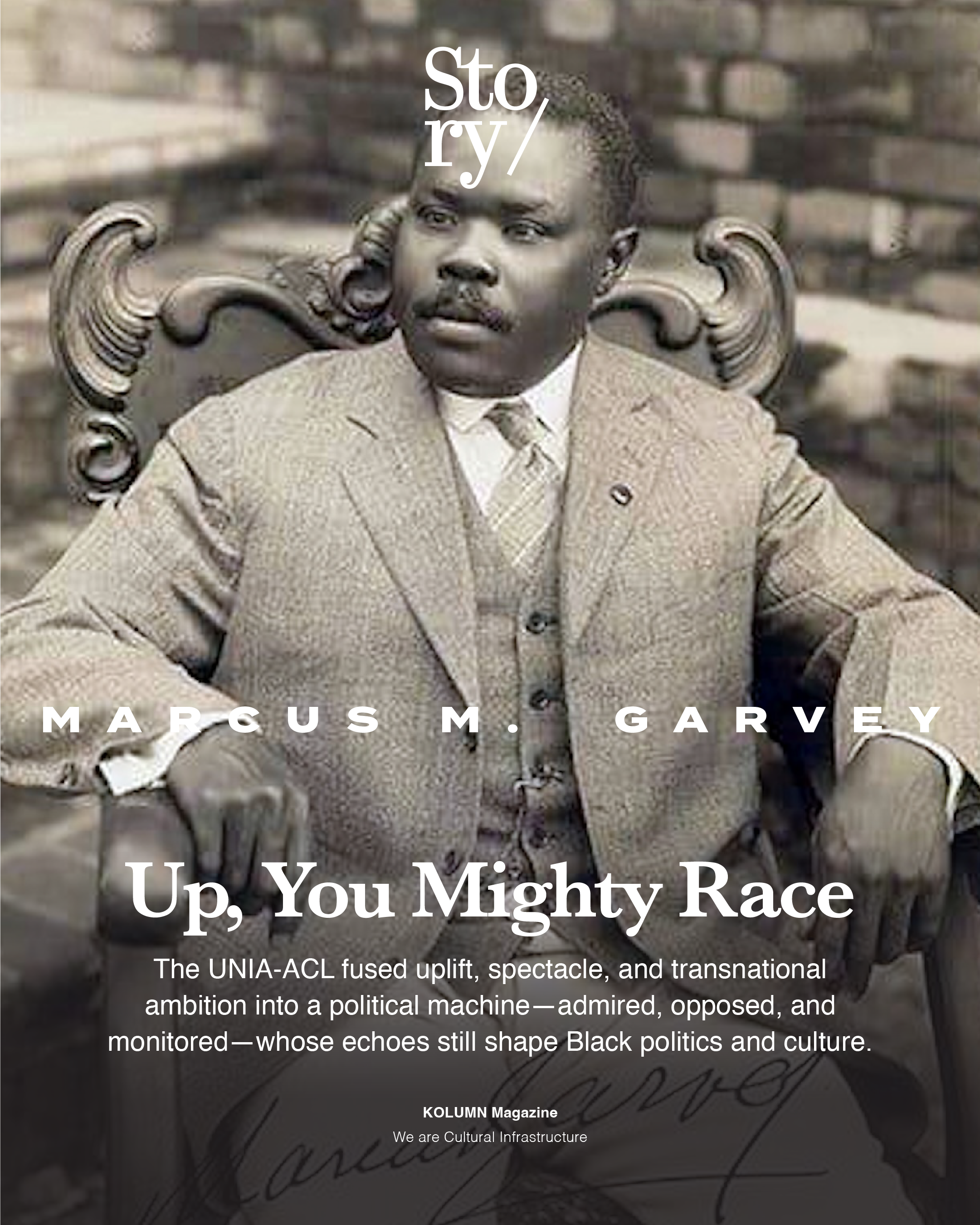

Up, You Mighty Race