Her life is not simply inspirational. It is instructive—about art, about power, about what it takes to keep a tradition intact while insisting that the country hear it.

Her life is not simply inspirational. It is instructive—about art, about power, about what it takes to keep a tradition intact while insisting that the country hear it.

By KOLUMN Magazine

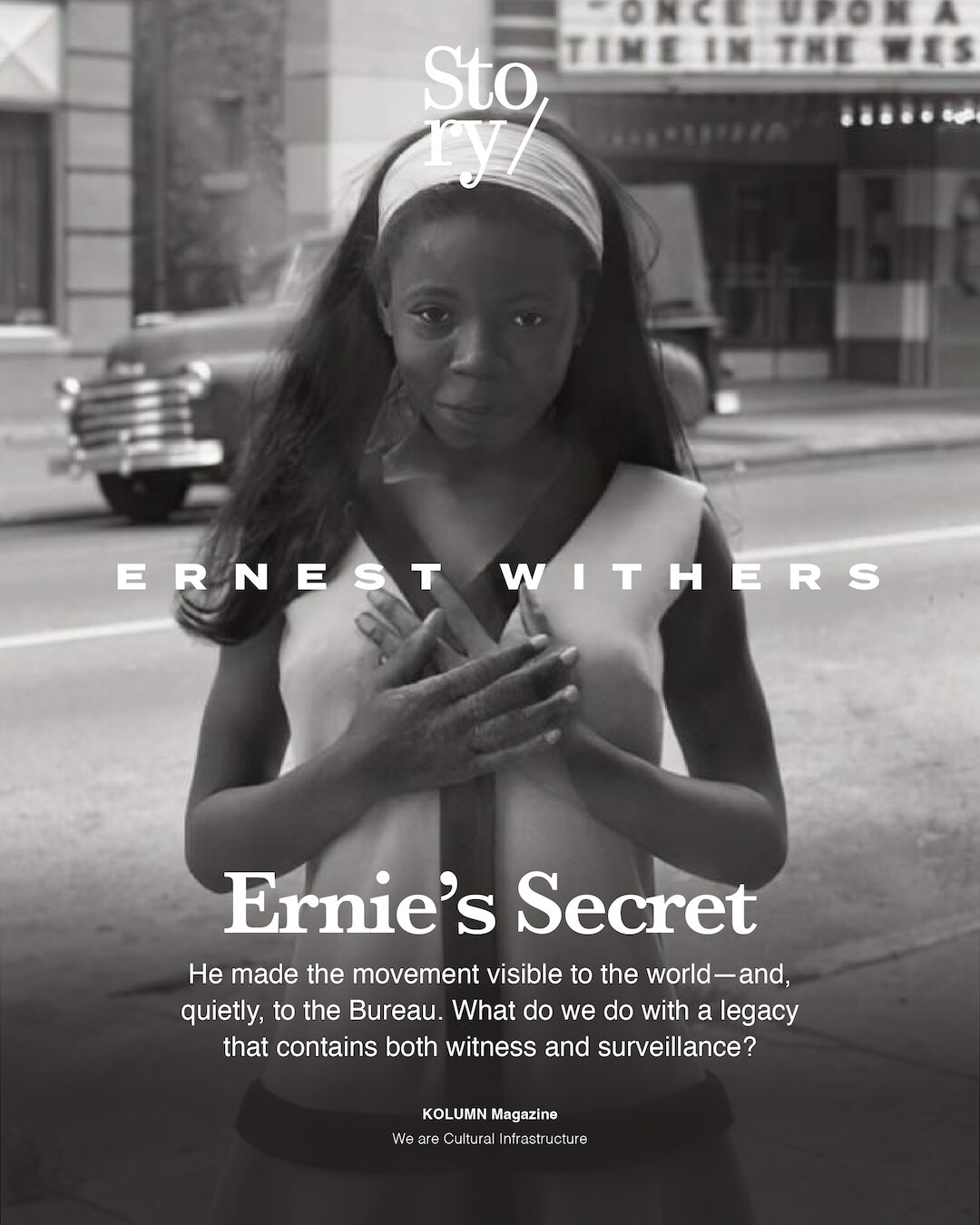

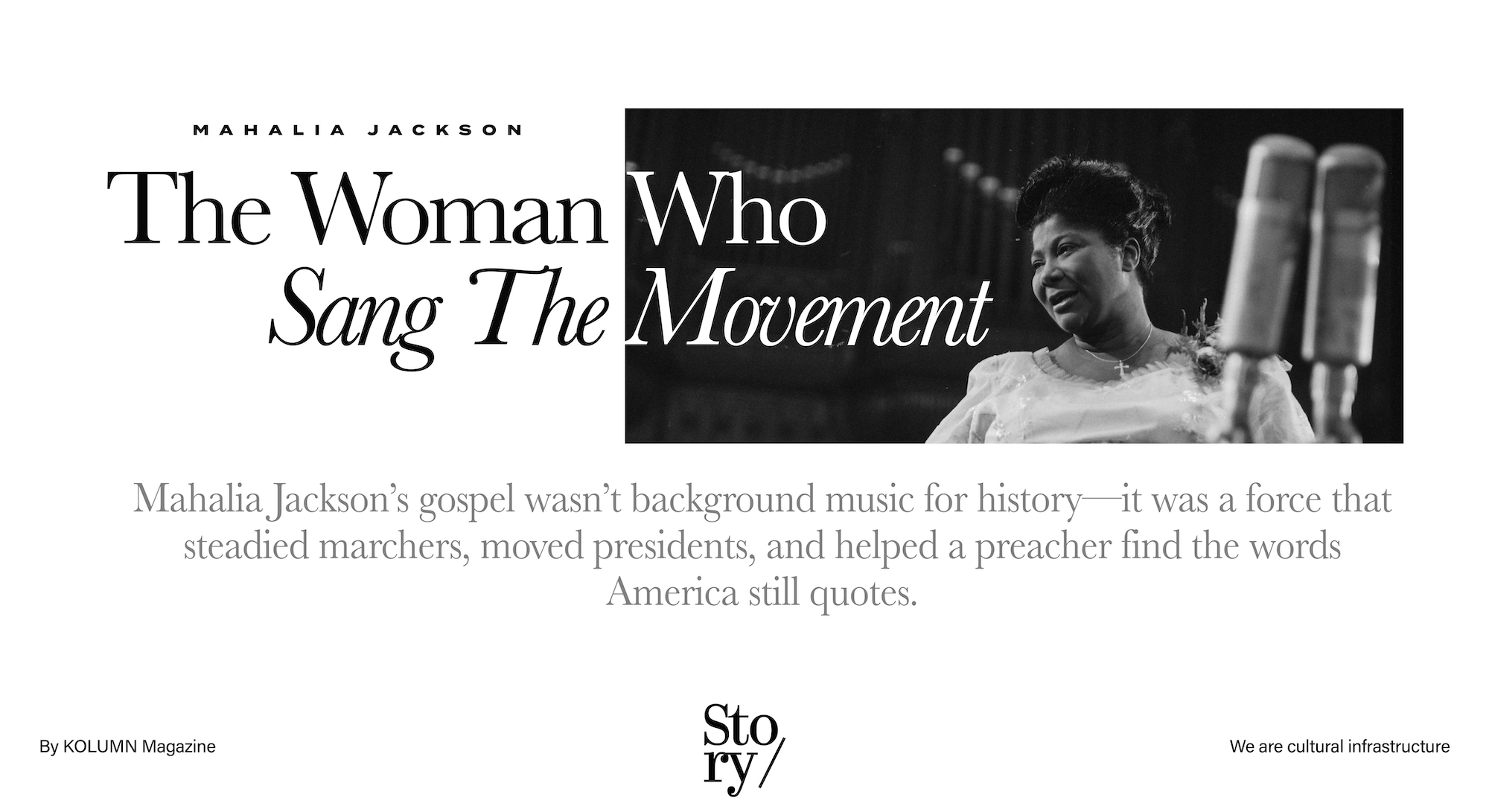

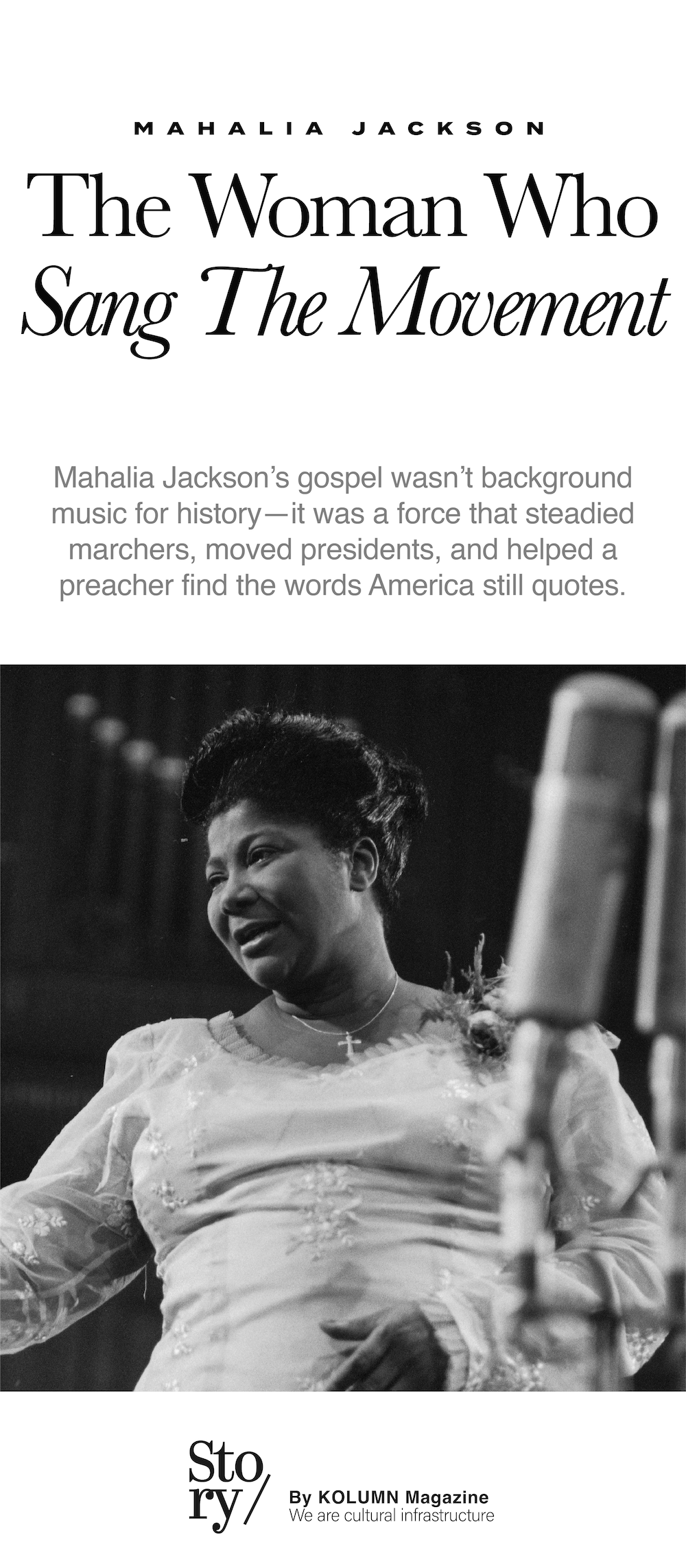

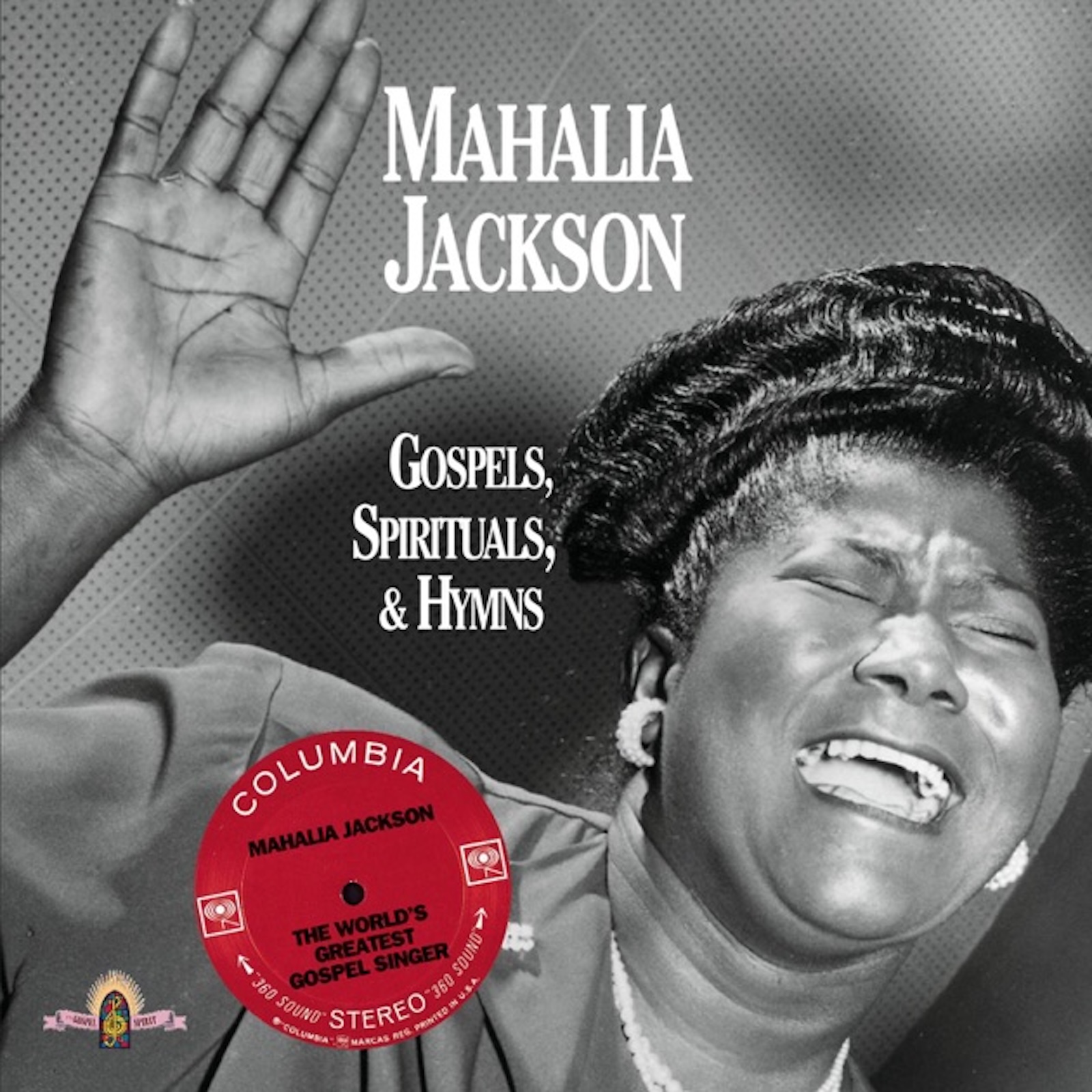

On the National Mall in August 1963, before Martin Luther King Jr. approached the microphones to deliver the address that would become shorthand for American aspiration, Mahalia Jackson stood near the lectern and sang. Accounts of what happened next have hardened into civic lore: the Queen of Gospel, positioned close enough to witness the preacher’s face, called out for him to “tell them about the dream,” nudging him toward the improvisation that would define the day. Whether one treats the moment as literal prompt or symbolic truth, it captures something essential about Jackson’s public life: she was not a decorative prelude to politics. She was part of the machinery of moral persuasion.

Jackson’s story is often told as inevitability—the greatest gospel singer in the world rising from humble origins, becoming the singular voice that both preserved and popularized a sacred tradition. But inevitability is a comforting narrative we project backward onto lives that were, in real time, precarious and contested. Gospel itself, in the early twentieth century, occupied an ambiguous status: beloved in Black churches, dismissed in elite circles, treated by many in the mainstream as provincial, unschooled, even improper. Jackson did not merely succeed within that tension; she lived inside it and made it productive. She carried the sound of the sanctified church into concert halls and television studios without allowing it to become mere entertainment. And as the civil rights movement built its public rituals—marches, mass meetings, funerals, speeches—Jackson supplied one of the crucial elements of their power: a music that could hold fear and hope in the same breath.

Her significance sits at three intersections. She is central to the commercialization and national legitimization of gospel music in the middle of the twentieth century, not as a compromise with secular tastes but as a cultural assertion that Black sacred art belonged on the biggest stages. She is a key figure in the civil rights movement’s emotional infrastructure—its ability to sustain collective risk, to organize courage, to turn private faith into public discipline. And she is an emblem of a particular kind of Black womanhood in American public life: commanding, maternal, spiritually authoritative, and politically consequential without being easily contained by the labels America preferred to hand Black women.

To write about Mahalia Jackson honestly is to resist turning her into a monument. Her voice could be majestic, but it could also be strategic. Her generosity could be expansive, but it was rooted in a clear-eyed understanding of what movements cost. She was capable of intimacy with ordinary people and access to the nation’s most powerful rooms. She maintained a fierce devotion to gospel’s boundaries even as she navigated the temptations of crossover fame. Her life, in other words, is not simply inspirational. It is instructive—about art, about power, about what it takes to keep a tradition intact while insisting that the country hear it.

New Orleans beginnings, and the early formation of a gospel sensibility

Mahalia Jackson was born in New Orleans on October 26, 1911, a city where Black music was both an inheritance and a battleground—where sacred traditions and secular nightlife often lived within a few blocks of each other, and where Jim Crow shaped every opportunity and every threat. She grew up in a devout Baptist environment, singing in choirs and absorbing the grammar of congregational music: the call-and-response patterns, the testimony embedded in phrasing, the way a singer could “work” a room by listening as much as projecting.

The story of Jackson’s childhood is frequently summarized in a few strokes—poverty, family hardship, church as refuge—and those elements are true, but they can flatten the deeper point: gospel was not simply her training ground; it was a worldview. In gospel, sound is not separate from meaning. The singer does not perform at the audience so much as with them, carrying the congregation’s emotional history into an audible shape. For a Black girl growing up in the early twentieth-century South, that tradition offered both discipline and permission: discipline in the insistence that the song must be truthful, permission in the idea that truth could be loud.

By the time Jackson left New Orleans for Chicago at sixteen, she was carrying more than a voice. She was carrying a set of expectations about what music should do. Chicago, swollen with the Great Migration, was full of new neighborhoods and storefront churches where Southern migrants attempted to rebuild the texture of home while confronting a different kind of segregation and a different tempo of urban life. The city also had an emerging gospel scene that would become one of the movement’s creative engines. Jackson entered that world not as a novelty but as a natural product of migration: the South’s sacred sound arriving in a Northern metropolis and reshaping it.

The King Institute notes that after moving to Chicago, Jackson sang in storefront churches and toured with a gospel quintet—work that suggests both artistry and hustle, the kind of steady, unglamorous labor that underwrites every later myth of discovery.

Chicago, the storefront church circuit, and the making of a “Queen”

If Jackson’s New Orleans years gave her gospel as a mother tongue, Chicago taught her gospel as vocation. Storefront churches were often dismissed as makeshift spaces—improvised sanctuaries in rented rooms—but they were also laboratories of style. In these congregations, the performance line between singer and congregation was porous; emotion could surge without apology; the music could stretch, repeat, accelerate, and testify until it reached a kind of cathartic truth. The gospel singer in this environment was not merely a vocalist. She was a conductor of communal feeling.

This was the ecosystem in which Jackson’s reputation grew. She released an early album in 1934, but the breakthrough came with “Move on Up a Little Higher” in 1947, a record the King Institute describes as the release that brought her fame. The same source notes its staggering scale: eight million copies sold, an achievement that signals not only popularity but a cultural hunger for this sound at a national level.

That sales figure matters because it complicates an easy story about gospel as niche. In the mid-century era—before streaming metrics and algorithmic virality—eight million copies suggests a phenomenon that traveled across regions, classes, and, crucially, racial boundaries. It also suggests that Jackson’s “crossover” was not an accidental seepage into the mainstream. It was a breakthrough built on demand: millions of listeners wanted what she offered, even if the cultural gatekeepers did not quite know how to categorize it.

Fame, however, did not dissolve the central dilemma Jackson faced: how to enter larger stages without sacrificing gospel’s integrity. The temptation for any singer in that era—especially a Black singer—was to accommodate the mainstream’s expectations, smoothing edges, adjusting repertoire, allowing sacred material to become simply “inspirational” entertainment. Jackson’s long-term significance is in how insistently she refused that dilution. She maintained gospel as her primary language while using fame to widen gospel’s audience, turning what could have been a compromise into a form of cultural leverage.

The King Institute notes that her stardom quickly translated into major performances, including sold-out shows at Carnegie Hall and a career that extended into radio and television in Chicago. Those platforms mattered not only because they amplified her voice, but because they normalized gospel’s presence in the national media landscape—an insistence that Black sacred art was not provincial but foundational.

A movement builds, and a singer becomes part of its infrastructure

It is tempting to talk about “the soundtrack of the civil rights movement” as if music were a secondary accompaniment to politics. But movements do not survive on demands alone. They survive on endurance, and endurance requires ritual: songs that can steady nerves before a march, music that can soothe rage without erasing it, melodies that remind people they are part of something larger than their individual fear.

Jackson’s relationship to the civil rights movement was not symbolic. It was practical. She appeared at events, sang at fundraisers, and used her visibility to bring attention to campaigns. The King Institute traces a key turning point: Jackson met King and Ralph Abernathy at the 1956 National Baptist Convention, and soon King asked her to perform in Montgomery for the foot soldiers of the bus boycott. In May 1957, she joined King on the third anniversary of Brown v. Board of Education, singing at the Prayer Pilgrimage for Freedom in Washington, D.C.—one of the movement’s early mass demonstrations that fused religious ritual with political claim-making.

This is where Jackson’s unique role becomes clear. Many celebrities supported civil rights, but Jackson’s support fit seamlessly into movement culture because the movement itself was, in many of its forms, a church-based phenomenon. As The Guardian reported in an interview context decades later, some gospel performers and church leaders were hesitant about overt politics, but King’s organization was church-based, allowing Jackson to participate without “leaving the church.” In that framing, her activism is not a detour from her artistry; it is an extension of the same moral logic.

A PBS segment on gospel and the movement goes further, describing Jackson as providing not only the soundtrack but also financial support “with her checkbook” and “emotional solace” in King’s darkest hours. That detail matters because it insists on a truth often underplayed in popular memory: Jackson was not merely present. She was invested.

The March on Washington, the “dream,” and the public myth that reveals a private truth

By 1963, Jackson was already an icon when the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom took shape. King asked her to perform “I Been ’Buked and I Been Scorned” before he spoke, the King Institute notes, placing her in the pivotal slot that would frame the crowd’s emotional readiness for his address.

Washington Post reporting on the March’s fiftieth anniversary captures the scene with the kind of sensory memory that marks historic days: the joy, the unity, the feeling that something was moving. In that account, Jackson’s words—“Tell them about the dream, Martin”—function almost like a stage direction that changes the script of history.

History.com, in a piece updated as recently as 2025, presents the moment as both performance and intervention: Jackson as lead-in vocalist and as someone who “plays a direct role” in turning the speech into one of the most memorable in American history.

Whether one treats the prompt as literal or as a condensed symbol of influence, it speaks to a larger reality: Jackson and King had a relationship that allowed for that intimacy. She was not a guest star. She was a trusted presence, someone who had shared the movement’s long nights, its fundraising needs, its spiritual demands. A singer who stands close enough to the podium to shout advice is not there as decoration. She is there as part of the team.

The King Institute preserves an even more revealing detail: King’s gratitude afterward. He wrote to Jackson that when he got up to speak, he was already happy, and if it was his “greatest hour,” she more than any single person helped make it so. This is the language of mutual reliance, not celebrity endorsement.

After the assassination: “Precious Lord” and the nation’s grief

If the March on Washington represents the movement at its most hopeful, the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968 represents its most traumatic rupture. Jackson’s presence at King’s funeral—and the specific song she sang—underscores the depth of her role. The King Institute notes that after King’s assassination, Jackson honored his last request by singing “Precious Lord” at his funeral.

This is one of those details that risks becoming a simple anecdote, but its significance is structural. Funerals in the Black church tradition are not merely private mourning; they are collective witness. To sing at King’s funeral was to help manage a national grief that was also a political emergency. It was to supply language when speech failed, to give the movement a way to cry without collapsing.

In this sense, Jackson’s activism is inseparable from her artistry because her artistry was itself a public service. She did not only “support” the movement. She helped it metabolize pain.

The politics of gospel success: Dignity, refusal, and the risks of crossover

Jackson’s mainstream success placed her in rooms where Black women—especially Black women rooted in church culture—were rarely granted authority. Her presence complicated a mid-century entertainment industry that often wanted Black performers as novelty but resisted Black performers as power.

One reason she mattered is that she modeled a kind of refusal that was itself political: the refusal to be embarrassed by Blackness, by the church, by a Southern sound. The Guardian’s description of gospel as the movement’s soundtrack is also an implicit description of Jackson’s cultural position: she stood for a tradition that was both spiritual and insurgent, both holy and socially disruptive.

The very phrase “Queen of Gospel,” often used casually, is worth taking seriously. A queen is not merely beloved; she is sovereign within her domain. Jackson’s sovereignty came from her ability to treat gospel not as a stepping-stone to “higher” forms but as the higher form itself. That posture is part of why her music could function as movement fuel. It was not apologetic music. It was declarative music.

This is also why her story remains relevant for contemporary debates about Black artistry and political responsibility. Jackson shows a model in which an artist’s public influence does not require a pivot away from tradition. It can come from deepening tradition until it becomes undeniable.

Mahalia Jackson as cultural infrastructure: A KOLUMN Magazine lens

KOLUMN Magazine, writing about Tulsa’s cultural geography and Black performance lineage, makes a telling observation: Jackson’s concerts in Tulsa churches and auditoriums functioned as both “spiritual gatherings and civic events,” with her voice “fused” to the emotional authority of the civil rights movement. It’s a local detail with national resonance. In that framing, Jackson’s appearances are not simply tour stops. They are community convenings—moments when a city’s Black public life gathers around a sacred art form that also carries political meaning.

That lens—Jackson as infrastructure—helps explain why she remains more than a historical figure. Infrastructure is what makes other things possible. Jackson made certain kinds of public feeling possible. She made it possible for mass meetings to feel coherent. She made it possible for grief to become collective rather than isolating. She made it possible for a movement to sound like itself.

And because she did this work through music, it can be underestimated by histories that privilege policy and courts over culture. But any serious account of civil rights has to explain not only what activists demanded but how they endured. Jackson is part of that “how.”

Memory, myth, and the responsibilities of telling her story now

There is a temptation in American culture to treat Black historical figures as symbols rather than people. Jackson is particularly vulnerable to this treatment because her voice invites reverence. Yet reverence can become flattening. The duty of journalism—and of any honest cultural history—is to keep the complexity intact: the strategic choices behind the grandeur, the labor behind the legend, the institutional constraints that shaped her options, the personal costs that seldom make it into celebratory narratives.

Modern media often returns to Jackson through the single, magnetic story beat of the “dream” prompt at the March on Washington. That moment is powerful, but it can also narrow her to a supporting role in someone else’s story. Jackson deserves the opposite: a narrative in which King is one part of her world, not the entire frame.

The better question is not whether she “helped” King. It is what she helped build: a moral soundscape in which the struggle for civil rights could be heard, felt, and sustained.

PBS’s description of her offering “emotional solace” and financial support provides a useful corrective, emphasizing the behind-the-scenes labor of sustaining a movement. The King Institute’s documentation of her repeated appearances at SCLC fundraisers and events builds the same point into the historical record.

The long echo: Why Mahalia Jackson still matters

Mahalia Jackson died in 1972, but her influence persists in at least four arenas.

First, in gospel itself: the genre’s mid-century national rise cannot be told without her. The fact that “Move on Up a Little Higher” sold eight million copies is not just a personal triumph; it marks a mass cultural shift in what America was willing to buy, hear, and carry into its homes.

Second, in the broader architecture of Black popular music. Gospel’s phrasing and emotional intensity shaped soul, R&B, and beyond. Even when later artists moved into secular repertoires, the gospel training remained audible—especially in the way they built crescendos, treated the audience as a participant, and used vocal power as testimony. (This is one reason Jackson is often invoked indirectly even in stories not “about” gospel: she sits upstream from much of American vocal culture.)

Third, in civil rights memory. The movement is often narrated through speeches and legislation, but its lived reality depended on cultural forms—songs, sermons, rituals—that could turn fear into action. Jackson’s presence at major events, her role at the March on Washington, and her singing at King’s funeral locate her inside the movement’s central ceremonial moments.

Fourth, in the ongoing debate about the relationship between art and responsibility. Jackson models a version of the public artist who is not “political” as branding, but political as practice: showing up, raising money, lending credibility, reinforcing morale. The Guardian’s reflection that gospel was the movement’s soundtrack—and that Jackson was foundational to that—clarifies why this matters. Movements are not just messages; they are lived communities. Music helps communities stay alive.

In an era when influence is measured in clicks and controversies, Jackson’s legacy offers a different metric: endurance, service, and the disciplined refusal to make sacred art small enough for mainstream comfort.

The voice as witness

Imagine the arc of her life as a sequence of rooms. A New Orleans church where a girl learns that singing is also speaking. A Chicago storefront where migrants reshape their faith into a new urban survival kit. A recording studio where a gospel song becomes a national best-seller. Carnegie Hall where sacred music is no longer treated as outside the canon. A Washington stage where a singer and a preacher help a crowd become a historical actor. A funeral where a nation’s grief requires a voice sturdy enough to carry it.

Jackson moved through these rooms with the same essential commitment: gospel must remain truthful. Truth, in her tradition, was not simply accuracy. It was alignment—between what you sing and what you live, between what you proclaim and what you’re willing to risk. That alignment is why her voice still sounds like authority decades later. It is also why her life continues to pose an uncomfortable question to the rest of us: what does it mean to have a gift, and what does it mean to spend it on something larger than yourself?

Mahalia Jackson spent hers. And America—whether it fully understands this or not—still lives inside the echo.

More great stories

The Master’s House Is Still Standing