The man behind the camera, the trusted presence near movement leadership, was revealed to have served as an FBI informant.

The man behind the camera, the trusted presence near movement leadership, was revealed to have served as an FBI informant.

By KOLUMN Magazine

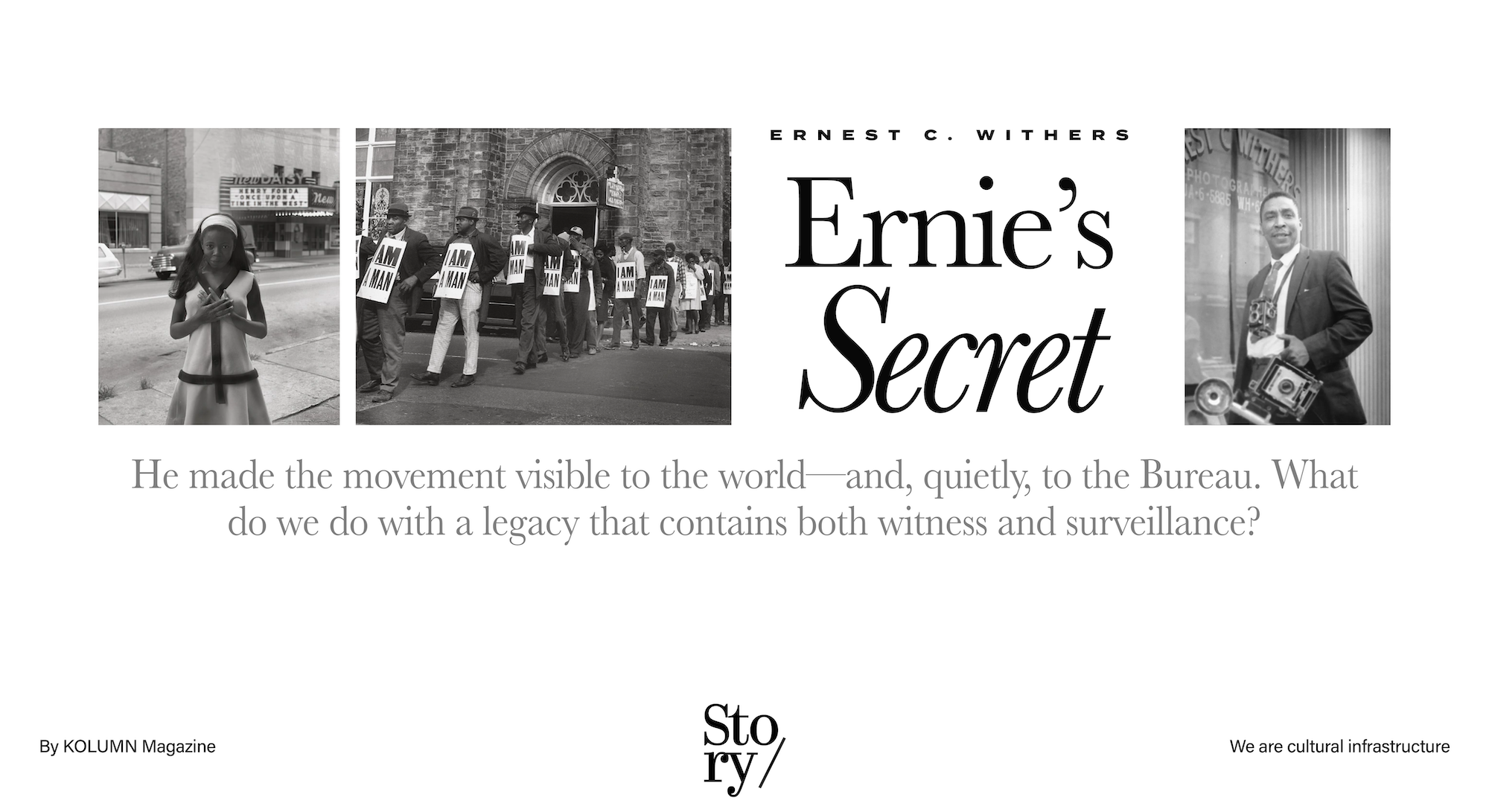

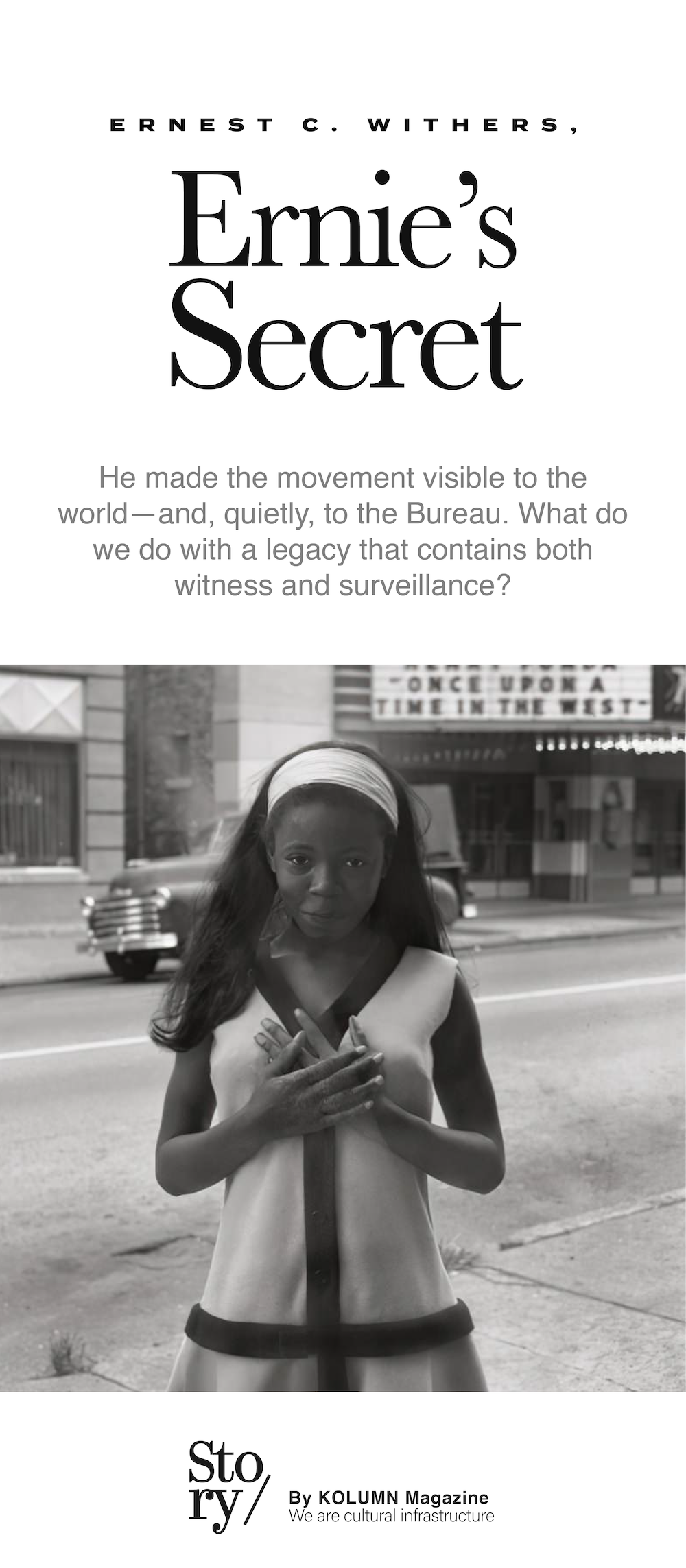

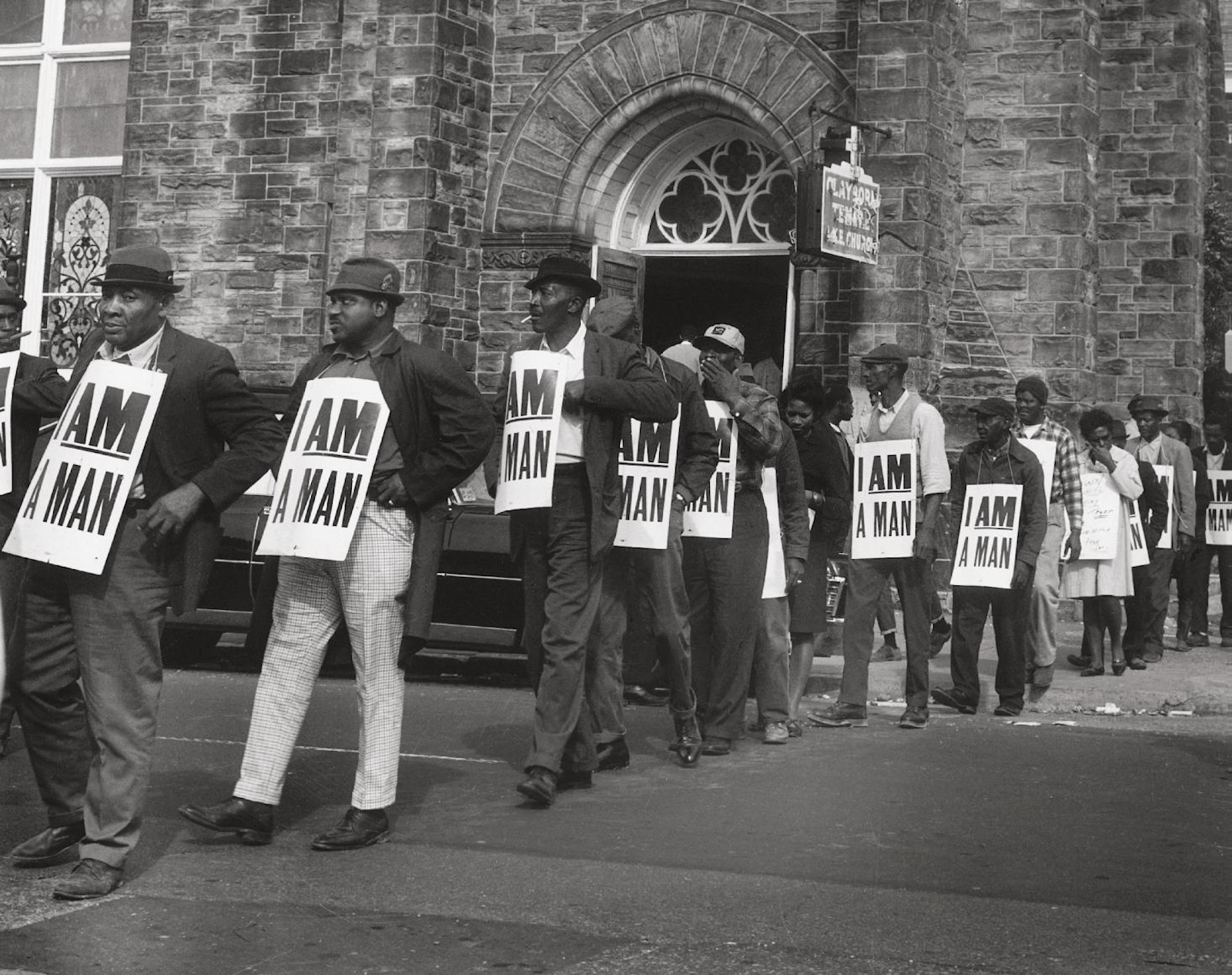

In the photograph, the signs seem to multiply as your eye moves across the frame: I AM A MAN, in bold capitals, held at chest height by Black sanitation workers gathered for a solidarity march in Memphis. The image is often described as inevitable—one of those documents that feels like it existed before it was made, as if the moral clarity of the words could summon its own evidence. Yet photographs do not happen by themselves. Someone had to be there, to see the geometry of protest and the choreography of dignity, to raise a camera at the moment when a local labor action became a national reckoning.

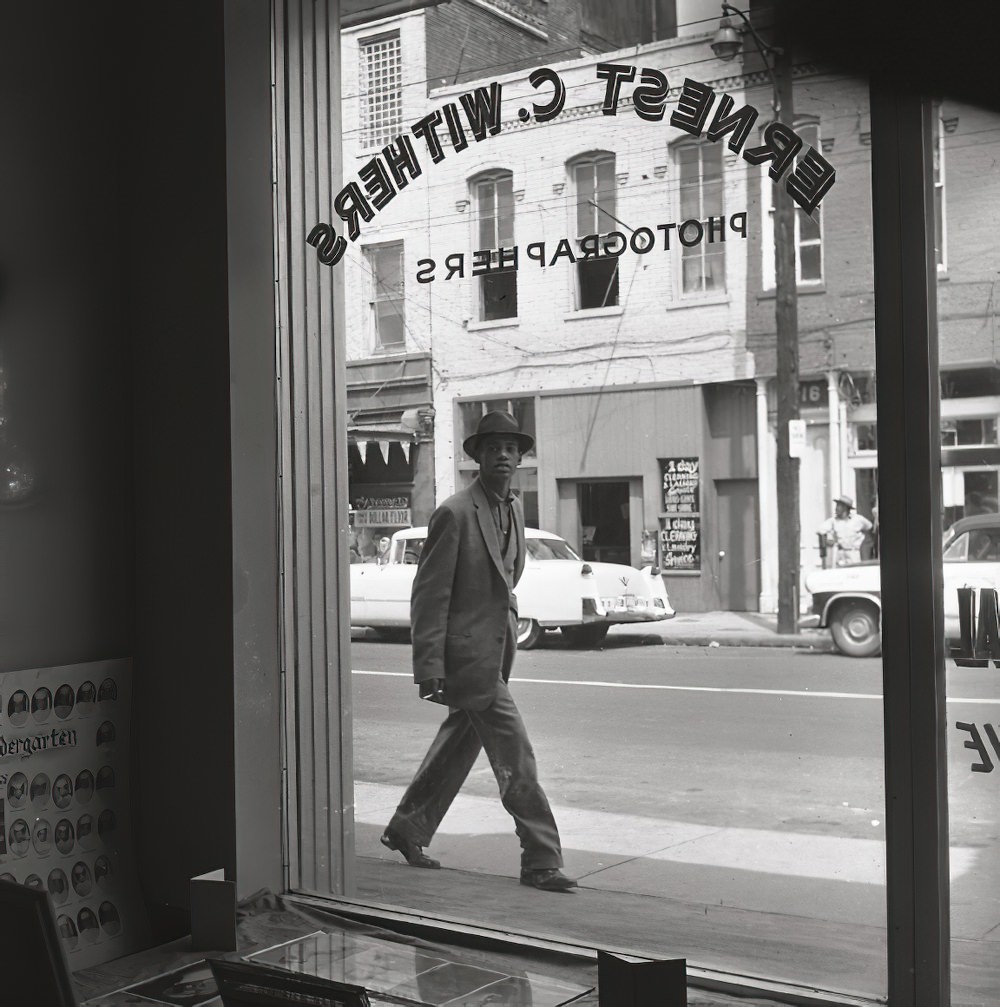

That someone was Ernest C. Withers, a Memphis-based photographer whose work—over decades—would help fix the visual vocabulary of Black life in the American South: the courtroom stare, the funeral procession, the bus window reflection, the backroom laugh, the bandstand sweat, the bleachers’ joy, the march’s fatigue. Institutions now teach from Withers’s images. Museums acquire and exhibit them. A Smithsonian education resource presents the sanitation-strike photograph as a landmark of American freedom struggle.

And then, for many viewers, the story turns. The man behind the camera, the trusted presence near movement leadership, was revealed to have served as an FBI informant, identified through documents and reporting that traced him to a confidential informant code associated with federal monitoring of civil-rights organizers. The revelation, first made public in 2010 reporting rooted in government records, did not erase the pictures; it changed how they vibrate.

To write about Ernest Withers responsibly is to hold two truths in the same frame: the extraordinary public value of his photographic record, and the profound questions raised by his clandestine relationship with a state apparatus that, in that era, trained its power against many of the same people Withers photographed. What follows is not a verdict so much as a reported portrait—of a life lived in relentless proximity to history, and of an archive that remains indispensable even as it becomes ethically complicated.

Memphis as a classroom: A photographer made by community

Withers is often described as a “civil-rights photographer,” and he was. But in Memphis, where his life began and largely unfolded, he was also something older and more local: a community chronicler. The Withers family and institutions that steward his work have emphasized the scope—well over a million images by some estimates—and the fact that much of it records the texture of everyday Black life: social clubs, church anniversaries, school events, sports leagues, family milestones, neighborhood rituals.

That community-first orientation matters because it suggests how Withers got what photographers most covet and rarely earn quickly: trust. Trust is not merely access to a front row; it is the permission to remain in the room when the room tightens—when grief arrives, when strategies are debated, when a public movement reveals its private seams. It is how you photograph not only events, but relationships.

Born in Memphis in 1922, Withers’s life would span Jim Crow’s brutal maturity, the midcentury movement’s surges and splinters, and the long afterlife of those struggles in memory and museum practice. Biographical summaries—by archival and educational organizations—note his training and early work, including military photography, and trace his professional path into the heart of Memphis’s Black press and cultural life.

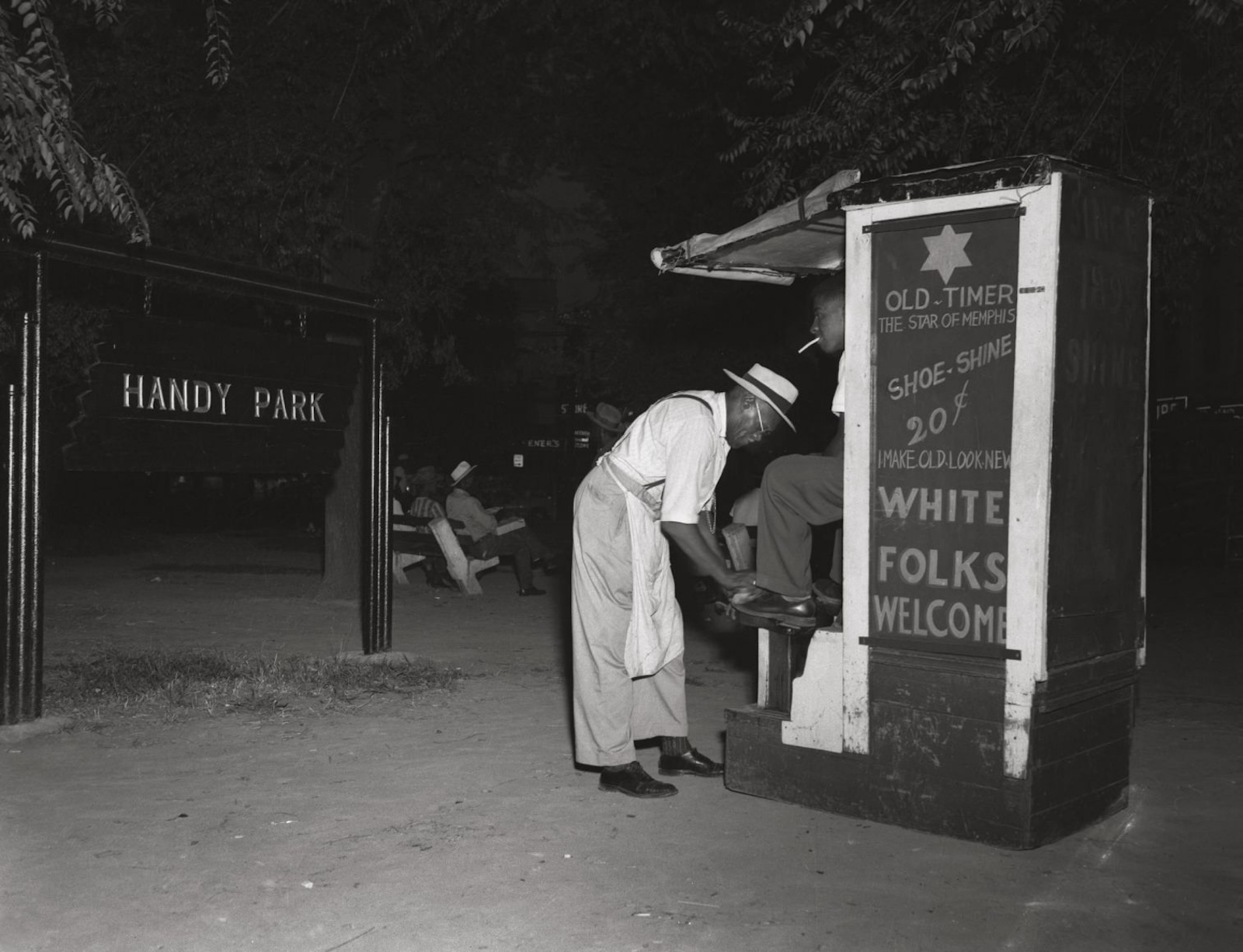

Memphis itself shaped the assignment list. It was a city where the Mississippi Delta’s musical innovations met the pressures of migration and labor; where Beale Street could be both a celebration and a ledger of exploitation; where Black institutions had to be resilient simply to exist. To photograph Memphis faithfully across decades was to photograph the South’s contradictions: beauty alongside coercion, invention alongside exclusion.

If Withers became famous outside the city for civil-rights iconography, inside Memphis he built something like a visual municipal record—a people’s archive. That breadth is central to his significance: he did not document Black history as an occasional special project. He documented it as daily work.

Learning the craft: The discipline of service and the eye of a journalist

Several accounts emphasize Withers’s formal training as a photographer during military service, which offered a technical foundation that many Black photographers of his generation could not access through traditional commercial pipelines. Memphis tourism and cultural write-ups frequently point to that training as a springboard into his later role documenting both segregation’s violence and Black life’s persistence.

That technical grounding mattered because Withers’s career would demand flexibility. He photographed in courtrooms and on streets, in clubs and in churches, in daylight and in the harsh contrast of flash. He produced images for news contexts and for private customers. He had to master the speed of photojournalism and the patience of portraiture.

The Black press was a major engine for this kind of career. Writing on Withers often connects him to Memphis’s Black newspaper ecosystem, including the Tri-State Defender, which functioned as both a news institution and a community bulletin—one of the places where a photographer could build consistent assignments and a recognizable visual voice. Accounts of his professional life also connect him to the broader world of Black media, including outlets associated with Ebony and Jet—publications that did not merely cover Black America but helped define its national self-image.

When mainstream American publications systematically under-hired Black photographers, the Black press served as both employer and training ground. Withers’s work is inseparable from that ecosystem: it is one reason his images so often feel intimate rather than extractive. He was not arriving as an outsider to “cover” a community. He was working inside a community that expected to see itself depicted with seriousness.

Early assignments that became national evidence: Emmett Till and the courtroom as theater

The civil-rights era’s most consequential images often come from spaces where power believes it is protected: courtrooms, police stations, official ceremonies. Withers’s career intersected dramatically with the Emmett Till case, where the spectacle of Southern justice—its rituals, its intimidation, its performative civility—had to be made visible to the nation.

Multiple sources credit Withers with documenting the Till proceedings in Mississippi in 1955, emphasizing the rarity and historical value of a Black photographer present to record the trial’s human choreography—the faces of witnesses, the posture of the accused, the posture of a region defending itself.

One image frequently cited in this context is the moment when Moses Wright identified Till’s abductors—an act of courage that, in photographs, becomes legible as physical risk. The Washington Post, reflecting on Withers’s archive and its later controversy, lists that courtroom moment among the many scenes Withers captured that now shape public memory of the movement.

In the movement’s visual history, the Till case is not just a story of tragedy; it is a story of documentation—of evidence forced into the open. Withers’s role in that documentary chain anchors his significance early: his camera became part of how America saw itself, sometimes against its will.

On the road with the movement: Montgomery, buses, and the image of resolve

Withers’s body of work sits at the intersection of movement organizing and media representation. He photographed not only famous leaders but also the infrastructure of protest: transportation, crowds, police presence, the physical labor of sustained resistance. Accounts of his career consistently place him at major movement flashpoints, including Montgomery and the broader struggle around desegregated transit. (memphistravel.com)

The bus, in civil-rights iconography, is a compressed stage. It is public and intimate at once; its windows turn people into framed figures; its seating becomes a literal diagram of power. The Washington Post points to Withers’s photographs of Martin Luther King Jr. and integration-era bus travel as examples of how Withers’s images became part of the era’s standard visual archive.

Such pictures do more than illustrate history; they make emotional claims. They show resolve without speeches, fatigue without statistics. They preserve the movement’s human scale—one face at a time.

Memphis music, Stax, and the cultural life that ran parallel to politics

If you only know Ernest Withers from civil-rights textbooks, you miss half the story. Withers photographed music with a kind of insider’s ease, documenting the Memphis scenes that would shape American sound: blues and soul, club life and studio life. A number of accounts emphasize his long relationship with Stax Records as an official photographer over many years—positioning him as a chronicler of cultural production as well as political struggle.

This matters for two reasons. First, it reminds us that Black life in the South was never reducible to oppression narratives. Even in the shadow of segregation, there was invention, glamour, humor, romance, ambition. Second, music and the movement were not separate worlds. They shared venues, audiences, and a language of aspiration. Memphis in the 1960s was a place where songs traveled alongside speeches, where style could be a form of politics, where a camera in a club might be only a few days away from a camera at a march.

Withers’s images of musicians—often shot with the same documentary seriousness as his images of activists—expand what counts as “history.” They help argue that culture is not decoration; it is part of the engine.

Baseball and Black excellence: The Negro leagues and the end of an era

Another major strand of Withers’s work is sports, particularly baseball and the Negro leagues. Some accounts stress that his lens followed not only the movement’s leaders but also the athletes and institutions that shaped Black public life. Memphis travel and cultural summaries note his documentation of Negro league baseball and the broader sports scene, positioning it as a key component of his six-decade archive.

Sports photography can be deceptively political. It records who gets celebrated, who gets sponsored, who fills stadiums, who appears in newspapers, who gets remembered. In the era when Black athletes were systematically undervalued or segregated, photographing Black sports life was itself a form of affirmation and record-keeping.

Withers’s breadth—music, sports, social life, protests—helps explain why his archive is so heavily mined. It is not a narrow folder labeled “civil rights.” It is a dense map of Black modernity in one of America’s most symbolically loaded regions.

“I AM A MAN”: Labor, dignity, and the making of an icon

The Memphis sanitation strike of 1968 has become one of the most analyzed episodes in American civil-rights history because it binds together issues that are often treated separately: labor rights and civil rights, economic exploitation and racial violence, local organizing and national attention. The strike began after the deaths of sanitation workers Echol Cole and Robert Walker—a reminder that the fight was not only about wages but about safety, about the value of Black labor and Black life.

Withers’s photograph of the marchers holding I AM A MAN signs became an emblem of that fusion. The New York Public Library identifies Withers as the photographer of the image and frames the strike as a protest against racial discrimination and unsafe working conditions, often met with violent opposition. The Smithsonian’s American Art education materials similarly present Withers’s sanitation-workers photograph as a central artifact of the era, now held within the collection of the National Museum of African American History and Culture.

The image works as iconography because it is both specific and universal. These are not anonymous silhouettes; they are men whose faces and coats and hats locate them in a particular time and city. Yet the phrase on the signs—simple, declarative—functions like a constitutional amendment written by ordinary people. The dignity claim is the story.

It is also an image that, in light of what later emerged about Withers’s relationship with the FBI, forces an uncomfortable question: what did it mean for an emblem of self-determination to be produced by a photographer who may have also been feeding information to a federal agency monitoring Black activism? The photo remains powerful. But power is not the same as innocence.

The motel room and the aftermath: Proximity to Martin Luther King Jr.’s final hours

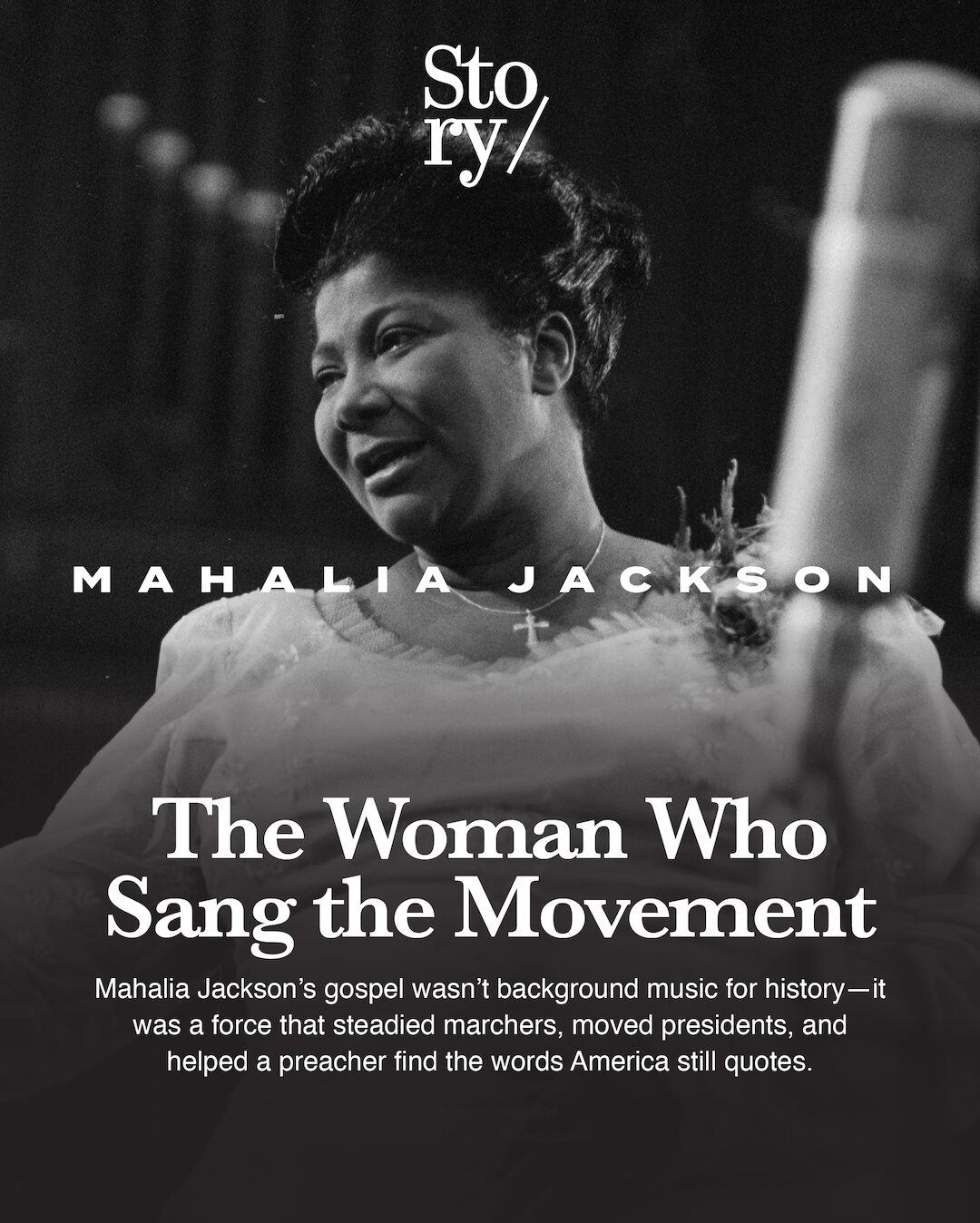

Withers’s camera was near the movement’s most intimate and tragic moments, including the days surrounding Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination in Memphis in April 1968. Public discussions of Withers’s legacy frequently return to this proximity—not only because it produced unforgettable images, but because it highlights the trust he was granted.

The scandal that broke after his death sharpened the meaning of that closeness. Accounts emphasize that Withers had been close enough to photograph King and his circle in moments of high vulnerability—and that this access, later understood in the context of informant activity, became a source of pain and anger for some movement veterans and scholars.

A photographer’s proximity can be read as service: the person who preserves the record when others are too busy living it. But it can also be read, in darker circumstances, as a form of surveillance. Withers’s life forces readers to contend with both possibilities at once.

The revelation: Documents, code names, and the informant story that changed the archive

The public learned of Withers’s informant status through a mix of investigative reporting and government records—an unraveling that itself illustrates how state secrecy can hinge on bureaucratic accidents. Reporting and commentary note that Withers was identified after an FBI document release did not fully redact his name, a detail echoed in contemporaneous coverage and later reflections.

The Guardian’s 2010 reporting captured the shock of the moment and quoted historian David Garrow describing Withers as “the perfect source” precisely because a photographer could plausibly be everywhere with an obvious professional reason. The Washington Post later summarized the origins of the revelation as emerging from 2010 reporting by Marc Perrusquia of the Memphis Commercial Appeal, describing how the discovery suggested Withers supplied information during a specific late-1960s window.

The legal and transparency dimensions of the case became their own story. The Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press wrote about FBI releases and FOIA litigation connected to the disclosure of Withers’s informant records, including references to his confidential informant designation and code name ME-338-R appearing in documents. Additional legal analysis discussing the matter describes the “R” designation as tied to a category of “racial informants” used to monitor civil-rights organizing—language that underscores how the federal surveillance state explicitly racialized its intelligence work.

In other words: Withers’s informant identity did not emerge as rumor. It emerged through records—partial, contested, and mediated by the law, but real enough to reframe his biography.

Motives, interpretations, and the danger of simple stories

Once an artist’s secret becomes public, a familiar pressure sets in: the desire to produce a clean moral. Withers becomes either hero or traitor, witness or collaborator, chronicler or spy. But the evidence and the context resist neat binaries.

The PBS ecosystem—through NewsHour segments, reporting tied to document releases, and the documentary The Picture Taker—has leaned into the complexity, framing Withers as both a maker of iconic images and a man whose motivations remain debated. The Guardian, reviewing the documentary and the broader story, explicitly warns against flattening him into a single archetype, describing the narrative as “more than just a hero or heretic.”

There are plausible motives that do not excuse the harm. Some interpretations emphasize coercion, economic necessity, fear, or the seductive power of proximity to authorities. Others emphasize agency: the fact that people made choices within constrained worlds, and that working with the FBI—especially against Black organizers—carried predictable consequences.

Yet journalism’s obligation is to separate what can be established from what is merely satisfying. What can be established, via records and reporting, is that Withers provided information and photographs to FBI handlers during a period when the Bureau was deeply engaged in monitoring and undermining civil-rights and Black power activism. What is harder to establish, definitively, is the internal story of why.

The impulse to diagnose motive can become its own kind of appropriation—turning a complicated Black life into a fable that serves contemporary needs. Withers’s legacy, perhaps, requires a different discipline: accepting uncertainty while still naming harm.

The human cost: Trust as a currency, and what gets stolen when it’s betrayed

Photography is built on relationships. Even in street photography, there is a social contract: a shared public space, a mutual risk. In movement photography, that contract becomes more intimate. Leaders and organizers are not simply “public figures”; they are people under threat, whose meetings and movements can carry lethal stakes.

The core ethical injury of the informant story is not that Withers worked for the government in the abstract. It is that he did so while occupying spaces where Black activists believed—reasonably—that the people in the room were invested in collective survival. The documentary and related reporting have emphasized how Withers’s access extended beyond public rallies into private strategy spaces—exactly the zones where surveillance can do the most damage.

This does not mean every photograph becomes suspect as an image. It means every photograph becomes suspect as a relationship. Viewers are asked to confront an unsettling possibility: that the same moment of trust that allowed a powerful image to exist may also have allowed information to flow toward repression.

That is why reactions remain mixed even among those who admire the photographs. The New Yorker’s contemporaneous commentary captured that split response—scholars and people who knew Withers weighing the value of the archive against the betrayal implied by the files.

The archive as institution: Museums, acquisitions, and the afterlife of a complicated witness

Even before the informant story became widely known, Withers’s photographs were already entering institutional permanence. Accounts note that his work has been archived and collected by major institutions, including the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture, which holds the sanitation-workers image in its collection.

In Memphis, stewardship of Withers’s images has taken the form of a dedicated collection and gallery apparatus that emphasizes both his international acclaim and his deep local roots. The Withers Collection describes him as a native Memphian recognized for iconic photographs of civil-rights leaders and the city’s music scene. Local reporting has also described the scale of the family-held archive and the labor of digitization and identification—work that is itself an act of historical reconstruction, attaching names and contexts to negatives that might otherwise become anonymous artifacts.

Archives are not neutral warehouses. They are arguments about what matters. When an institution elevates Withers, it is elevating not only his images but also a way of seeing Black Southern life: as worthy of sustained attention, worthy of artistry, worthy of record.

The informant revelation does not negate that institutional logic. It complicates it. It forces museums and audiences to ask: can a body of work be essential even if its maker participated in systems that harmed the very subjects he documented? The answer, in practice, appears to be yes—because the alternative is historical amputation. But “yes” is not the same as “no problem.”

How to look now: Reading Withers in the age of surveillance

To look at Withers’s photographs in 2026 is to look through multiple eras at once. We see the 1950s and 60s. We also see 2010, when document releases and reporting changed the interpretive frame. We also see now: a world in which surveillance is both more pervasive and more normalized—phones and platforms doing at scale what informants once did in person.

That layered context can make Withers’s archive feel newly urgent. Hyperallergic, reviewing exhibitions of his civil-rights photographs, argued for the continuing relevance of his images as evidence and as a reminder of how struggles over rights recur across time. PBS NewsHour’s discussion of the Withers story via journalist Wesley Lowery’s “Ernie’s Secret” reporting underscores how the informant narrative has become a contemporary case study in government monitoring and historical memory.

Seen this way, Withers becomes less a singular moral puzzle and more a lens on a broader American pattern: the state’s tendency to monitor Black political life, and the ways ordinary professions—photography, journalism, clerical work—can be recruited into that monitoring.

But there is a risk in making Withers purely symbolic. He was not only an instrument of history; he was a working man with a studio, a family, and a city’s worth of clients. Any fair account has to keep his full scope in view: the church events and ballgames alongside the marches, the cultural life alongside the politics. He photographed Black life as living, not only as resisting.

The significance, stated plainly: What Ernest Withers gave the record—and what he took

Ernest Withers’s significance rests on three interlocking facts.

First, he produced a vast visual archive of Black life across the better part of a century, with particular depth in Memphis and the Mid-South—an archive that includes iconic civil-rights moments and the everyday social world that made those moments possible.

Second, he created some of the defining images through which America remembers the civil-rights movement, including the Memphis sanitation strike’s “I AM A MAN” march—an image now canonized through major cultural institutions.

Third, credible records and reporting indicate he served as an FBI informant during a period when the government was aggressively surveilling and undermining Black activism—an involvement that complicates, without erasing, the meaning of his work.

If you are searching for a single sentence that resolves the tension, you won’t find an honest one. Withers’s life refuses that kind of closure. The pictures remain. The harm remains. The questions remain.

And perhaps that is the most journalistically faithful way to end: not with a pardon or a condemnation, but with an insistence on holding the whole negative up to the light. In that light, Ernest Withers is still what he always was—a man close enough to history to make it visible, and close enough to power to remind us visibility can be dangerous.

More great stories

The Master’s House Is Still Standing