A Louisville attorney and civil-rights organizer breaks barriers in the Kentucky legal system; she becomes a prosecutor; she is abducted, beaten, drowned; the case is investigated repeatedly; fingerprints and witnesses exist; decades later, there is renewed attention and additional forensic review; and still no courtroom accounting.

A Louisville attorney and civil-rights organizer breaks barriers in the Kentucky legal system; she becomes a prosecutor; she is abducted, beaten, drowned; the case is investigated repeatedly; fingerprints and witnesses exist; decades later, there is renewed attention and additional forensic review; and still no courtroom accounting.

By KOLUMN Magazine

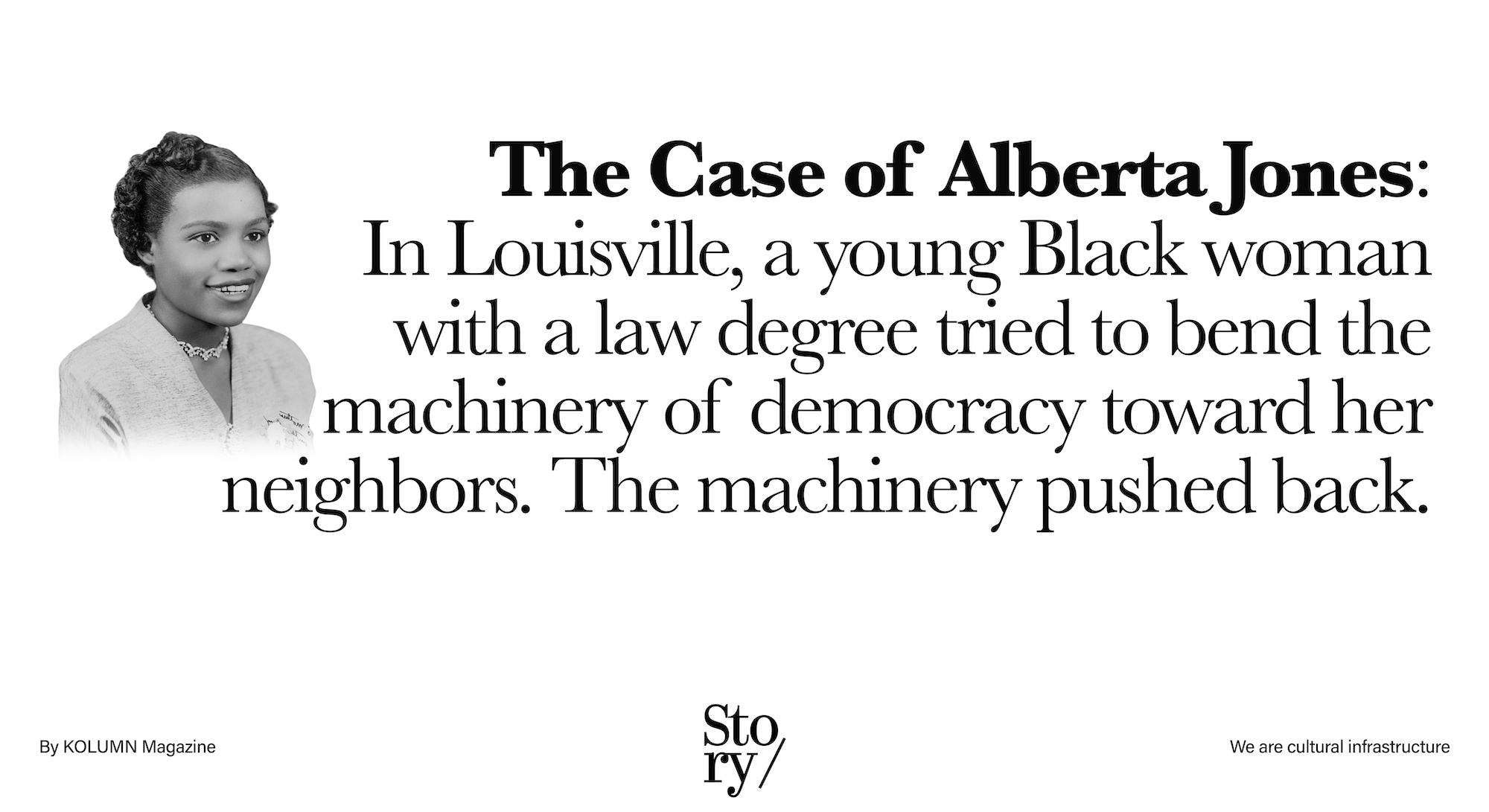

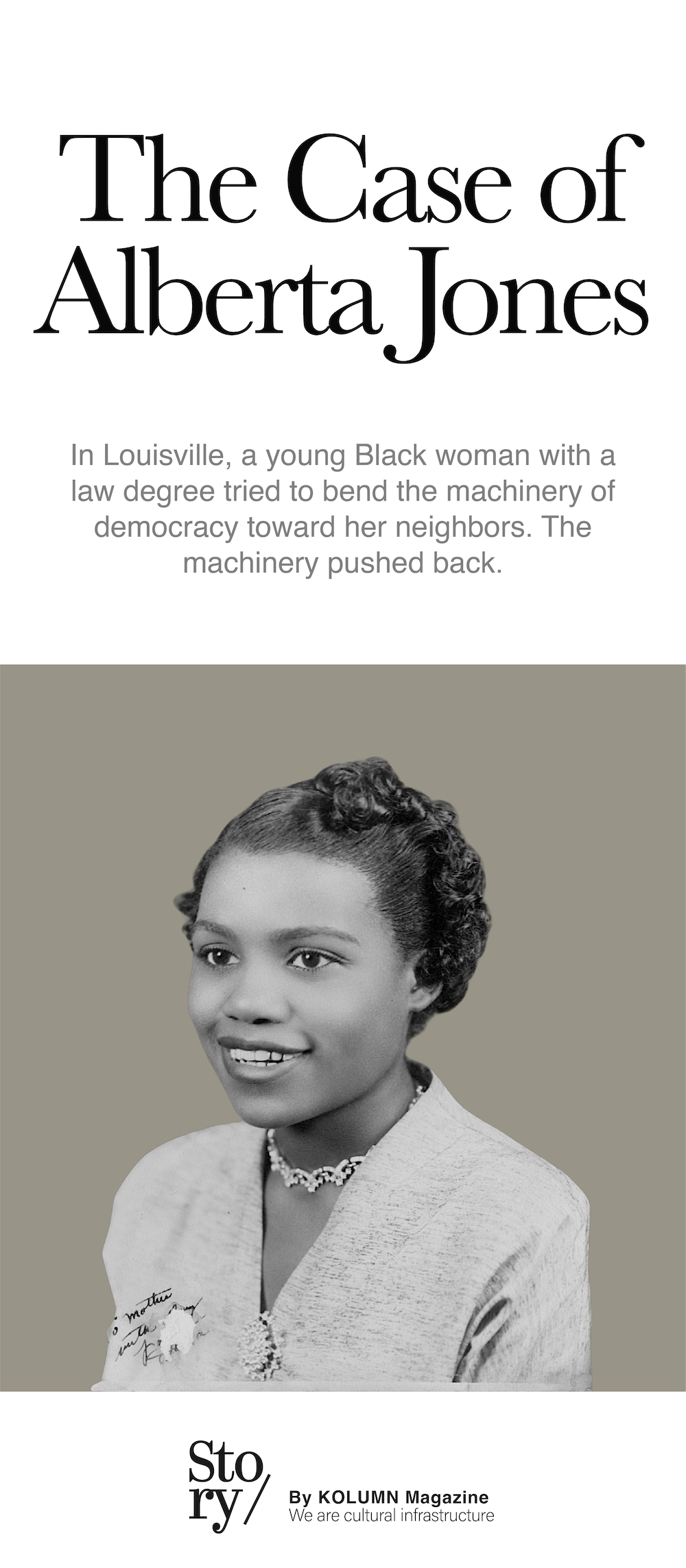

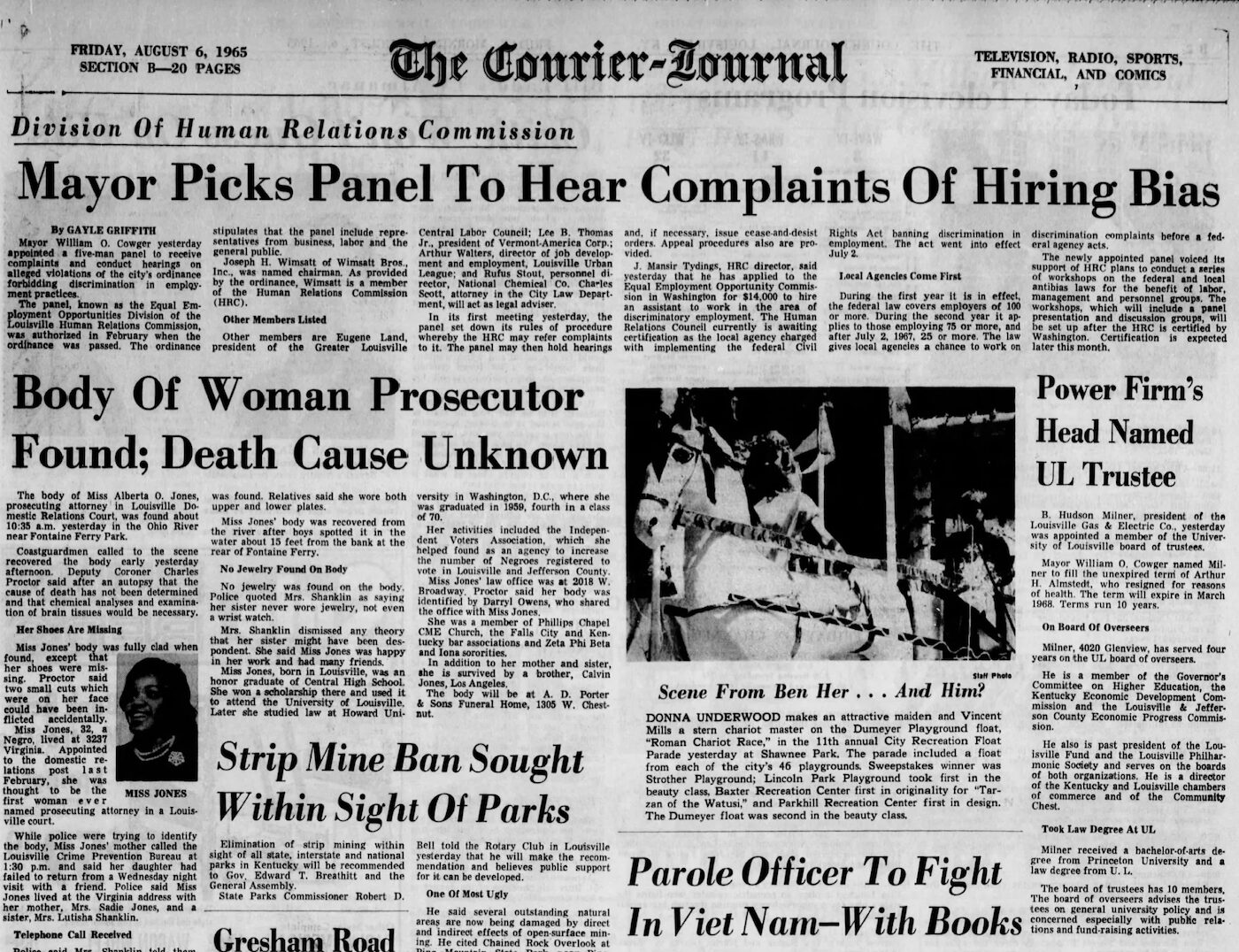

On a summer morning in Louisville in 1965, the Ohio River carried an unbearable message. The body of Alberta Odell Jones—34 years old, a prominent Black attorney, and Louisville’s first female prosecutor—was found floating near Fontaine Ferry Park. In the blunt language of police work and bureaucratic recordkeeping, her death would be categorized, revisited, argued over, and filed away. In the lived language of the city she served, it landed as something else: a warning flare and a void, the sudden removal of a person who had been building Black political power with the unglamorous tools of law and electoral mechanics.

To understand why Jones matters—why her name keeps returning in Louisville’s civic memory, why journalists and documentarians have treated her case as more than an old homicide, why artists and institutions have moved in recent years to publicly honor her—you have to see her whole life as a single project: making citizenship real in a place and time designed to keep it abstract. Jones did not become significant only because she was murdered, nor only because she was “first” in a list of institutional milestones, though the milestones matter. Her significance lives in the connective tissue between her roles: attorney and organizer, courtroom professional and street-level democrat, a woman who moved between the private negotiations of a boxing contract and the public teaching of voters how to operate a voting machine.

In the years since her death, the question “Who killed Alberta Jones?” has persisted partly because it remains unanswered. But the deeper, more durable question is why her work required such courage in the first place—and what it reveals about the fragility of justice when the law’s gatekeepers are also the keepers of local power.

Louisville’s rules and the making of a lawyer

Alberta Odell Jones was born and raised in Louisville, Kentucky, in an era when segregation was not simply social custom but a set of enforced expectations. Louisville’s Black neighborhoods, its schools, its job ladders, and its political representation were shaped by boundaries that could be crossed only with cost—sometimes personal, sometimes professional, sometimes lethal. Jones’s early academic record reads like a quiet defiance of that landscape: she graduated from Louisville Central High School and went on to Louisville Municipal College, an institution created for Black students barred from the University of Louisville before desegregation. She graduated near the top of her class.

Her path to the law was not linear in the way biographies prefer. She attended the University of Louisville’s law school for a period before transferring to Howard University School of Law, one of the central training grounds for mid-century Black legal talent and civil-rights strategy. Howard was not merely a credential factory; it was an intellectual engine for the long project of dismantling Jim Crow through litigation and political pressure. A Black woman entering that world in the 1950s entered a profession that had been built to exclude her, and she did so at a time when even many reform-minded institutions still treated women lawyers as novelties or exceptions.

Jones returned to Kentucky and passed the bar in 1959, becoming one of the first Black women admitted to the Kentucky bar—an achievement that carried both prestige and an immediate burden of representation. Every courtroom appearance and every client intake became, whether she wanted it or not, a referendum on whether the door should have opened for the next person.

If you want to locate the radicalism of Jones’s ambition, it’s here: she pursued a professional identity that required institutional validation from systems not designed to validate her. That act alone—becoming a Black woman lawyer in Kentucky in 1959—was a form of political work.

The practice, the clients, and a larger idea of representation

Jones opened a practice in Louisville and quickly became known in local circles not just as an attorney but as someone with uncommon drive and range. Her professional memberships and affiliations placed her inside the infrastructure of the legal profession while her activism placed her in the streets and meeting rooms where civil rights were fought in everyday terms.

One of the most cited episodes of her early career is also one of the most symbolically rich: she became the first attorney for a young boxer named Cassius Clay—later Muhammad Ali—and negotiated his first professional fight contract. This story often gets told as a remarkable footnote: a trailblazing Black woman lawyer representing a future global celebrity. But it is more revealing than a footnote. It shows Jones operating in a field where money, race, and power converge—sports promotion and contract law—at a time when Black athletes were routinely exploited by managers and business structures built to siphon their earnings. The contract itself has been treated as a piece of civic history in Louisville’s Ali ecosystem, a reminder that Jones’s skill was not confined to civil-rights symbolism; she had technical competence and negotiating leverage.

Jones’s representation of Ali also hints at a broader theme of her life: she understood “representation” in both meanings of the word. She represented clients in the legal sense, but she also represented a community’s claim to full participation in public life. In mid-century Louisville, those meanings were not separate. A Black lawyer’s success could become community proof-of-concept: evidence that the professions were not naturally white, that the courthouse did not belong to one group alone, that the language of contracts and statutes could be spoken fluently by someone the system tried to silence.

Voting rights, but make it practical

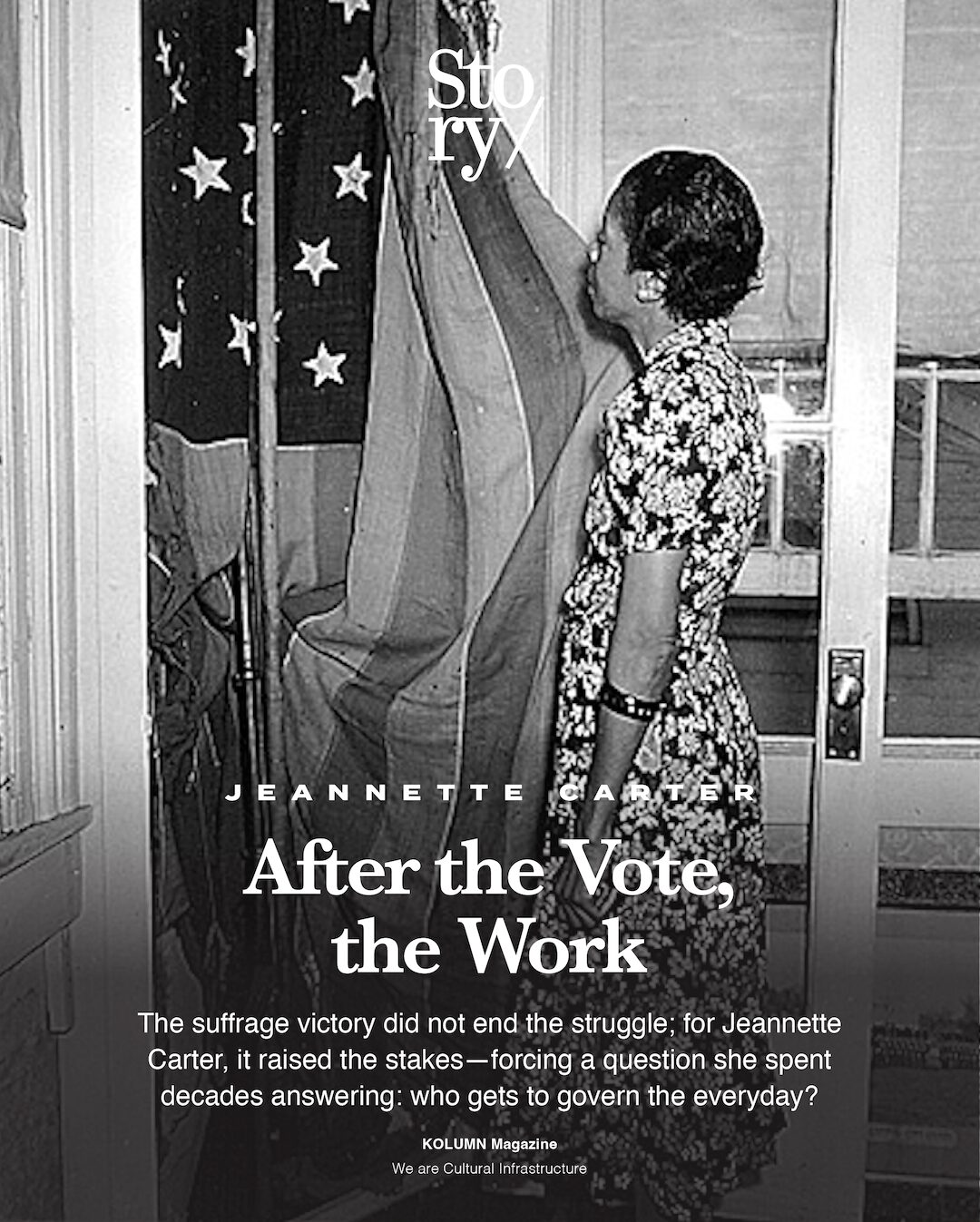

If Jones had done only one thing worth remembering, it might still be her work to expand Black voting power in Louisville—not as rhetoric, but as logistics.

After participating in civil-rights activity in Louisville and attending the 1963 March on Washington, Jones helped form and lead the Independent Voters Association (IVA), described in later government summaries as a nonpartisan organization dedicated to enfranchising Black voters and providing information on political candidates.

The details matter here because they show what voting rights looked like on the ground. Jones rented voting machines and held classes to teach Black residents how to use them—an almost startlingly practical intervention. The act implicitly acknowledges what segregation-era civic systems often relied on: not only formal barriers, but engineered friction. If voting technology is unfamiliar, if instructions are withheld, if intimidation is ambient, participation drops. Jones attacked the problem at its operational level.

This kind of work doesn’t always read as glamorous in the archive. It creates fewer iconic photographs than a march, fewer quotable speeches than a courtroom victory. But it can be more destabilizing to a local power structure because it changes who selects the power structure.

Jones’s era sits inside a broader national story of Black enfranchisement struggling against local resistance. By the mid-1960s, the Voting Rights Act would become federal law, but the fight was never only federal. City-by-city, precinct-by-precinct, Black organizers had to build the capacity to translate rights into votes. Jones was part of that ecosystem in Louisville, and the fact that her IVA role is emphasized even in later Justice Department summaries underscores how central it was to her identity.

City Hall, the courthouse, and the meaning of “first”

In February 1965, Jones was appointed as a prosecutor in Louisville’s Domestic Relations Court, frequently described as making her Louisville’s first female prosecutor—and in some accounts, the first woman prosecutor in Kentucky.

A “first” can be a ribbon cut for a system, but it can also be a target painted on a person. Jones entered a role associated with state authority—charging decisions, courtroom arguments, institutional legitimacy—while also remaining a figure associated with Black civic mobilization. That dual identity had consequences. Even decades later, summaries of her murder return to the idea that her “high profile” as a Black woman prosecutor and her civil-rights activity shaped public speculation about why she was killed.

Jones’s public profile rose in a Louisville that was still negotiating desegregation and Black political participation. The city’s legal and political institutions were not neutral landscapes; they were arenas where inclusion was contested. When Louisville Downtown Partnership and civic sponsors honored Jones with a “Hometown Hero” banner in 2017, the press materials emphasized her legal trailblazing and explicitly tied it to civil-rights activism—marches, organizational membership, and her voting-machine classes. Even the memorial language makes clear that her “firsts” were inseparable from movement work.

This is crucial for interpreting her significance. Jones was not simply an exceptional individual who rose above her time. She was part of a collective push, and her excellence was one way that push became visible.

The last night, and what is known

In any account of Alberta Jones, the temptation is to let the murder dominate the narrative. It is dramatic, unresolved, and—in its violence—viscerally symbolic. But responsible storytelling has to distinguish between what is documented and what is inferred.

What is documented, according to later Justice Department records and journalistic reconstructions, is that Jones was last seen alive hours before her body was found. She had been driving a rented white 1965 Ford Fairlane. A neighbor account described hearing a woman screaming and seeing a woman dragged into a white car that sped toward the river. Investigators later found the rental car abandoned with evidence of blood and struggle; an autopsy concluded drowning as the cause of death, with documented injuries to her head and face consistent with assault.

The violence described in later reports is blunt: dragged from a car, struck in the head, thrown into the river. The Washington Post’s 2017 reconstruction framed the sequence in similarly direct terms and emphasized that the case remained unsolved despite fingerprints and witnesses.

The Justice Department’s 2023 “Notice to Close File” memo adds investigative texture: multiple fingerprints were found on and in the car; the case was investigated repeatedly across decades; a grand jury at one point declined to indict; and later reviews included a fingerprint match identified through FBI systems in 2008, followed by an interview and a reported failed polygraph, but no prosecutable federal case.

This is the structure of the tragedy: abundant suspicion, persistent interest, repeated investigation, and still no legal closure.

The long afterlife of an unsolved civil-rights-era killing

If Jones had been murdered and the case solved quickly, she would still be historically important. But the unsolved nature of her killing has turned her story into something like a civic mirror: each generation looks into it and sees a reflection of its own questions about whose lives are protected, whose deaths are investigated, and what institutions do when the victim is both marginalized and politically consequential.

Her case is now frequently discussed within the category of unresolved civil-rights-era violence—murders that were neglected, mishandled, or deprioritized at the time, and later revisited amid national reckonings. The Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division has treated her murder as one of these cases, and its closing memo explicitly frames the matter in civil-rights investigative terms while also stating the legal obstacles to prosecution, including the expiration of federal statutes of limitations and lack of evidence tying living individuals to the crime.

PBS FRONTLINE’s Un(re)solved project and podcast also place Jones in a broader narrative of long-delayed accountability, emphasizing how cold cases move (or fail to move) across institutional time. In the FRONTLINE podcast, a fingerprint match found years later becomes a focal point for hope and frustration—the kind of forensic breadcrumb that suggests solvability but does not guarantee justice.

It is important not to overstate what these later investigations prove. A fingerprint is not a full narrative. A polygraph is not a verdict. And institutions have their own incentives when they reopen or close files: sometimes driven by new evidence, sometimes by political pressure, sometimes by the desire to demonstrate responsiveness without the capacity to prosecute. The ethical approach is to remain anchored to the record: repeated investigative efforts did not produce charges, and the Justice Department ultimately closed its review without finding a prosecutable federal civil-rights violation.

Why her work made enemies without requiring a conspiracy

In the mythology of unsolved murders, the mind reaches for grand plots. Jones’s story has not been immune to allegations—some suggesting official involvement or cover-up. The Justice Department memo notes that speculation existed about possible involvement by police or city officials but states there was a lack of evidence substantiating such claims or tying a specific living official to her murder.

But even without a conspiracy, Jones’s work could generate danger.

Consider what she did, concretely: she expanded Black voting capacity and taught people how to vote effectively; she moved in the courthouse as both insider and reformer; she represented prominent clients; she held a prosecutorial role in a city where policing and prosecution were not racially neutral functions. Any one of those could threaten someone—an abusive spouse targeted by domestic relations enforcement, a political faction threatened by new voters, a criminal actor angered by prosecution, a racist individual seeking to enforce terror, or an opportunist who believed a Black woman alone at night was vulnerable. The record shows investigators explored multiple theories, including those connected to her work and her personal life, but did not resolve the motive.

This is where her story becomes larger than a single case file: it illustrates how civic work can create exposure. Jones’s activism was not abstract. It was applied power. It moved resources and outcomes. And applied power, even when legal, produces backlash.

Public memory: Banners, parks, portraits, and the insistence on naming

For decades after her death, Jones was known in Louisville, especially in Black civic circles, but not widely commemorated in the city’s mainstream landscape. That began to change notably in the 2010s.

In 2017, Louisville’s “Hometown Hero” program installed a large banner honoring Jones downtown. Coverage by Louisville Public Media described her as a figure who combined legal firsts with civil-rights leadership and noted the renewed interest in her case as it was reopened locally. The official press release language emphasized her achievements—Kentucky bar passage, prosecutorial “first,” representation of Ali—and her voting-rights tactics, including renting voting machines to teach Black residents how to vote.

In the years after Breonna Taylor’s killing in Louisville, images circulated showing Jones’s banner “watching over” protests—an accidental but potent visual argument about continuity: two Black women, separated by more than half a century, both becoming symbols of whose lives are protected and whose deaths spark civic rupture.

Institutional commemoration has expanded as well. Kentucky’s “Women Remembered” exhibit added new inductees in the mid-2020s, including Alberta Jones, situating her not simply as a local figure but as a statewide “trailblazer” whose portrait belongs in the Capitol’s official narrative.

These memorial acts matter because they change what a city teaches itself. A banner is not justice, but it is an argument about who deserves to be seen. A portrait in a capitol is not prosecution, but it is an official admission that the state’s history includes—and requires—the labor of a Black woman lawyer who worked against the grain.

Her significance now: What Alberta Jones clarifies about democracy

Alberta Odell Jones’s life clarifies something that can be easy to forget in the era of high-level political commentary: democracy is made operationally, by people doing work that can look small until you measure it against the resistance it overcomes.

Her work reminds us that enfranchisement is not merely the right to vote but the capacity to vote effectively. Renting voting machines and teaching people how to use them is a form of civic engineering, the kind that shifts outcomes without ever making the front page.

Her career reminds us that “equal justice under law” is not self-executing. It requires people willing to enter institutions and insist, case by case, that the law apply. Becoming a prosecutor—the state’s voice in court—while being a Black woman with civil-rights commitments is itself a test of whether the system can tolerate accountability from someone it did not plan to empower.

And her death, unresolved, reminds us that violence has often been one of the tools used to discipline such insistence. Even when no single perpetrator is named, the effect of an unsolved killing can be political: it tells others that the cost of civic leadership might be paid in blood—and that the system may not balance the scales afterward.

In the Justice Department’s closing memo, there is a kind of bureaucratic finality: the file is closed, the statute has run, the evidence does not yield a prosecutable federal case. But Jones’s story demonstrates the difference between legal closure and historical closure. A case file can be closed while the civic wound remains open. The wound stays open because what was lost was not only a life but a set of future possibilities: the cases she would have tried, the voters she would have mobilized, the women she would have mentored, the kind of institutional authority she might have normalized simply by occupying it.

The most honest ending is the unfinished one

There are stories journalism likes because they conclude. This is not one of them.

The documented record establishes the outline: a Louisville attorney and civil-rights organizer breaks barriers in the Kentucky legal system; she becomes a prosecutor; she is abducted, beaten, drowned; the case is investigated repeatedly; fingerprints and witnesses exist; decades later, there is renewed attention and additional forensic review; and still no courtroom accounting.

What remains is not only the question of “who,” but the challenge of what a city does with an unfinished truth. Louisville has begun to answer in one way: by naming Jones publicly, placing her face on buildings, situating her inside the state’s commemorative architecture, and telling newer generations that she belonged in the rooms where power was exercised.

Those acts do not solve a murder. But they do something else that matters in the long run: they refuse erasure.

And refusal, in a story like Alberta Odell Jones’s, is not sentiment. It is strategy—the same kind of strategy she practiced when she taught people how to vote, when she walked into courtrooms that did not expect her, when she treated the law not as a promise but as a tool that had to be gripped tightly to be used at all.

More great stories

Black Is Beautiful Had a Cameraman