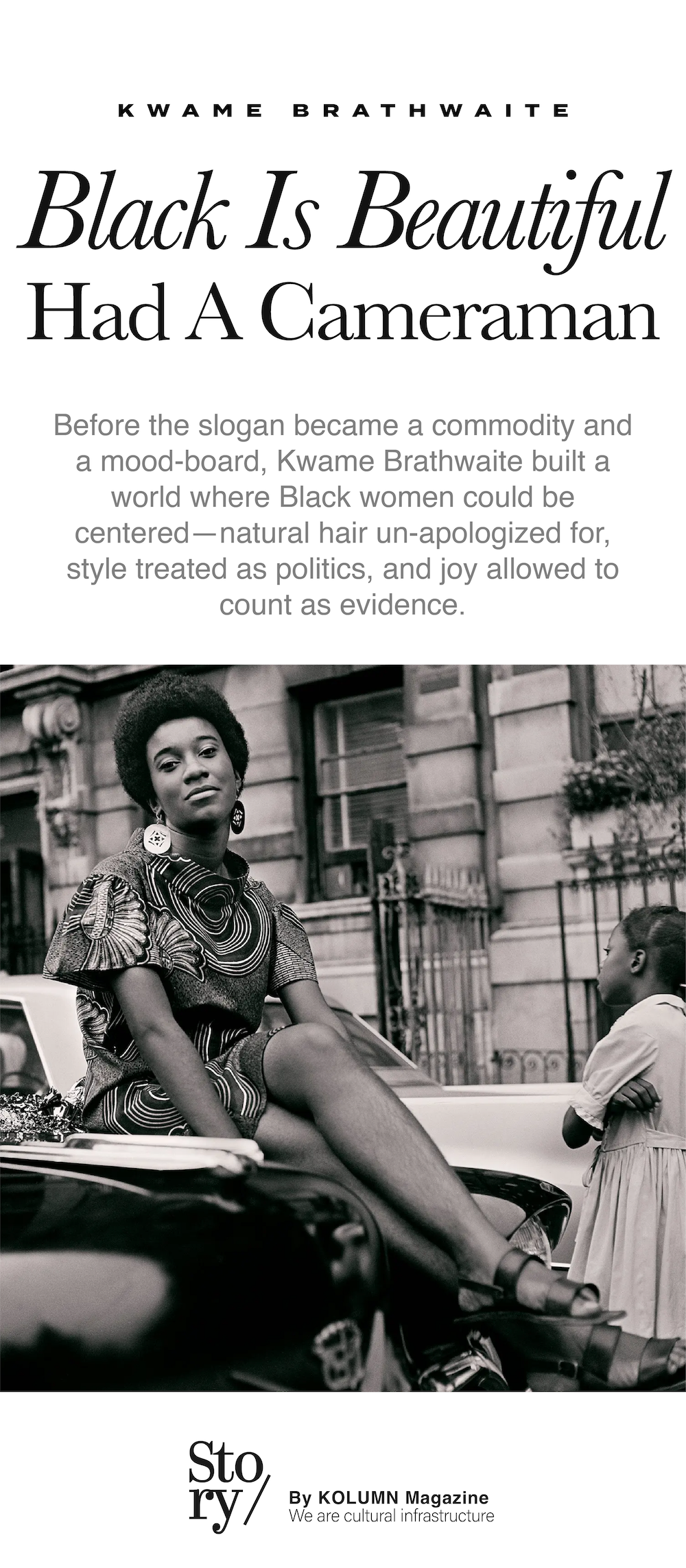

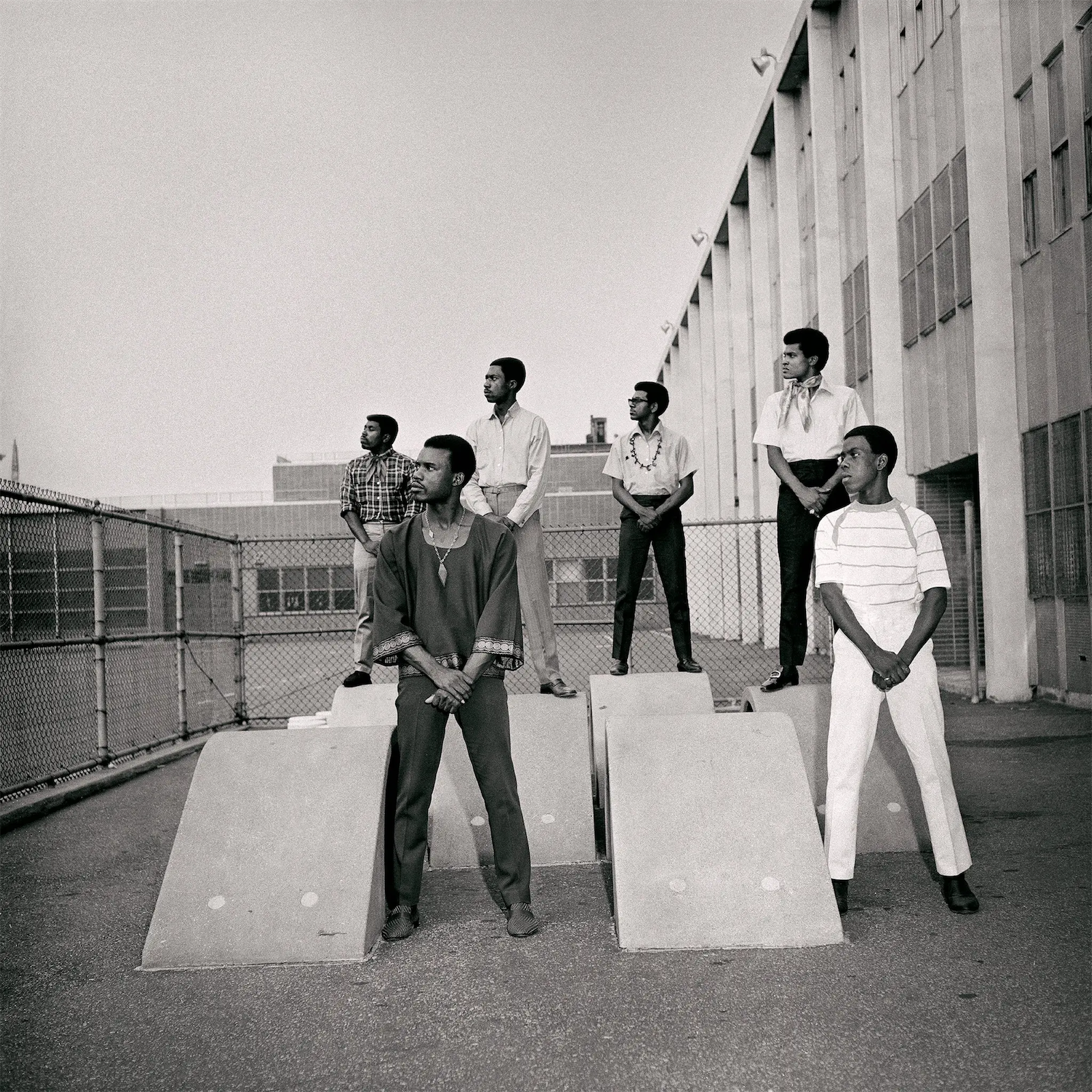

Kwame Brathwaite captured moments as simply true: a woman is beautiful; a community is vivid; a neighborhood contains glamour and seriousness; Blackness is not a defect to be managed but a field of design.

Kwame Brathwaite captured moments as simply true: a woman is beautiful; a community is vivid; a neighborhood contains glamour and seriousness; Blackness is not a defect to be managed but a field of design.

By KOLUMN Magazine

There are phrases that feel older than the people who spread them—slogans that arrive in the ear like inherited truth, as if language itself has always known what it means. “Black is beautiful” is one of those phrases now: printed on T-shirts, repurposed in ad campaigns, invoked in speeches, folded into the casual grammar of affirmation. But for most of its public life, the phrase has traveled without its cameraman, without the person who made it visible enough to stick.

Kwame Brathwaite—born in Brooklyn on January 1, 1938, and dead in New York on April 1, 2023—spent more than six decades creating photographs that functioned as a kind of infrastructure. Not simply art objects, not merely documents, but supporting beams for a cultural argument: that Blackness could be centered, styled, celebrated, and understood on its own terms.

The argument took many forms. In the 1960s, it was a fashion show in Harlem where Black women wore their hair natural and their bodies un-edited to fit white beauty doctrine. It was a collective—African Jazz-Art Society & Studios (AJASS)—that treated culture as organizing, jazz as a political inheritance, and design as persuasion. It was the Grandassa Models, a troupe and an idea, formed to reject the narrow hierarchies of colorism and respectability that even Black publications often reproduced.

Over time, the argument expanded into photojournalism: Brathwaite photographing musicians, athletes, rallies, everyday Harlem scenes, and moments of Pan-African encounter that linked Black America’s interior life to the wider diaspora. And then, in the way so many Black cultural legacies behave in the American record, the argument was partially buried—kept alive inside community memory and local archives, but rarely granted the institutional status it had earned.

What makes Brathwaite essential in 2026 is not only that he helped popularize a slogan—though the record is clear that his images and organizing were central to that spread. It is that he built a visual language for Black possibility at a time when mainstream America relied on visual languages of Black lack: lack of refinement, lack of beauty, lack of innocence, lack of complexity. He photographed against that regime, insisting—quietly but relentlessly—that Black people were not a “problem” to be explained, but a people to be seen.

A camera as a response to violence

Brathwaite’s origin story is often told with a particular kind of moral clarity: a young Black boy sees what photographs can do, and decides to wield that power. Accounts of his life repeatedly note the catalytic impact of photojournalism—images of Black suffering and Black truth that reached him in print and taught him the stakes of representation.

This is not unusual in the history of Black photographers. The camera has long functioned as a counter-weapon: a tool that can refute lies by producing proof, and can repair psychic damage by producing dignity. But Brathwaite’s genius was to understand, early, that proof is not only the image of brutality. Proof can be glamour. Proof can be tenderness. Proof can be a woman in a carefully chosen garment, lit like she owns the future.

That sensibility developed alongside a second one: organizing. In 1956, as a teenager, Brathwaite co-founded what became AJASS, a collective anchored in the South Bronx that promoted jazz performances and African cultural presentations and treated Black artistry as a civic project. The National Gallery of Art’s description of him emphasizes those early influences—Marcus Garvey’s teachings and the movement of ideas that connected Black cultural pride to political self-determination.

AJASS mattered because it was a rehearsal space for the future Brathwaite would photograph. It gathered musicians, designers, hairdressers, writers, and visual artists into a single ecosystem. It taught him that cultural production isn’t an afterthought to politics; it is one of politics’ primary engines. And it placed him in Harlem’s nightlife and performance circuits—spaces where style, sound, and aspiration were always already arguments about freedom.

When Brathwaite later became closely associated with the Apollo Theater’s musical world—photographing artists and performances—he was not arriving as an outsider. He was documenting a scene he helped energize, a community that understood jazz and Black modernity as inseparable.

Naturally ’62 and the invention of a new public image

On January 28, 1962, a show took place at the Purple Manor, a Harlem nightclub, that has since become a kind of origin point in retellings of the “Black Is Beautiful” era. The event—Naturally ’62—was explicitly framed as an “African coiffure and fashion extravaganza,” and it did something that now seems obvious only because it succeeded: it put Black women’s natural hair and Afrocentric styling onstage as a standard, not a deviation.

In much of mainstream American fashion culture at the time, Black women were either absent or present only through heavily policed aesthetics: straightened hair, lighter skin privilege, narrow body expectations. Brathwaite and his collaborators weren’t simply objecting. They were building a replacement system—an alternative beauty economy with its own rituals, contests, and iconography.

This is where the Grandassa Models enter, as both a troupe and a theory. The Grandassa women were not one “look.” Their skin tones ranged; their body types varied; their hair, most crucially, was allowed to be itself. Brathwaite photographed them in ways that made the point unmistakable: rich color backdrops, poised stances, jewelry and garments that did not ask permission from Eurocentric taste. The photographs were not begging to be included in the mainstream; they were declaring that the mainstream was beside the point.

This is also where Brathwaite’s work diverges from a certain kind of documentary photography. Many documentary traditions in America have trained the lens on Black pain as if pain were the most “truthful” register of Black experience. Brathwaite certainly photographed political struggle, and he did work as a photojournalist for Black publications. But his most radical contribution may be the way he made joy legible as political data.

A MoMA tribute later described him as “Keeper of the Images,” a phrase that implies more than authorship: stewardship, custody, a sense that images belong to a people and must be protected. The Grandassa photographs embody that ethic. They are portraits, but they are also safeguards—visual custody of a moment when Black women claimed the right to define themselves.

Harlem as studio, Harlem as audience

One of Brathwaite’s most important strategies was geographic: he built the work in Harlem, among Harlem people, and for Harlem to recognize itself. Tanisha C. Ford’s writing for Aperture—based on years of research into Brathwaite, AJASS, and the aesthetics of Black freedom—emphasizes that the operation was both creative and entrepreneurial: a studio space near the Apollo, sitting fees, self-produced ephemera, a local economy of image-making that did not depend on white institutions for validation.

That detail matters because it reframes “Black Is Beautiful” not as a vibe that floated into existence, but as a business model and a distribution strategy. Brathwaite and his collaborators understood that images become movements only when they circulate. They worked to make photographs that could appear in Black publications domestically and internationally, and they built events—shows, contests, cultural gatherings—that created audiences hungry to see themselves differently.

In other words: the movement did not wait for a museum. It created itself as public culture first.

That approach aligns Brathwaite with a longer Harlem photographic lineage. KOLUMN Magazine’s recent essay on James Van Der Zee argues that Van Der Zee’s portraits didn’t merely show Harlem—they showed Harlem seeing itself, building a self-image capable of resisting caricature. Brathwaite, working later and under different political pressures, pursued a related ambition: the camera as a mirror that does not flatter so much as fortify.

The difference is the era’s urgency. Where Van Der Zee chronicled a community’s aspiration amid the Harlem Renaissance, Brathwaite photographed the moment when aspiration had to turn into confrontation—when hairstyle, clothing, and photography became frontline arguments against a dominant culture that insisted Black features were defects.

The photograph as a fashion editorial—and as a manifesto

Brathwaite’s images of the Grandassa Models read today like fashion editorials. They have the backdrops, the styling, the deliberate poses, the sense of a look being launched. That resemblance is not accidental; it is one reason the photographs have proven so easily legible to later generations, including fashion houses and contemporary designers who draw on the era as a reference point.

But to call them “fashion photographs” without insisting on the political context is to miss what Brathwaite was doing. The images are not selling garments; they are selling a reordering of value. Vogue’s coverage of his work and the story of Naturally ’62 emphasizes precisely this dynamic: the show and the photographs were built to push back against Eurocentric beauty standards and to recenter Afrocentric aesthetics as legitimate and desirable.

The New Yorker’s account of the Grandassa Models underscores how radical it was, in the 1960s, to put Black women in front of the camera with natural hairstyles and un-edited features—and to treat that presentation as the standard rather than the exception. Even within Black media ecosystems, lighter skin and straight hair often functioned as the default. Brathwaite’s photographs intervened in that internal hierarchy as much as they confronted white exclusion.

This is why the images resonate so strongly now, in an era that talks openly about colorism, texturism, and the politics of “professional” appearance. Brathwaite’s photographs are not merely beautiful; they are evidence that these debates are not new. They are a visual record of Black people already doing the work of redefining beauty long before corporations learned to monetize the language of inclusion.

Music, nightlife, and the craft of being present

If Brathwaite had only photographed the Grandassa Models, his significance would still be considerable. But his archive is larger: jazz clubs, concert halls, backstage corridors, street scenes, rallies—Black life in the full range of its public performance. The Art Institute of Chicago, reflecting on his work, emphasizes how his relationship to music shaped his photography, and how the images capture Black cultural energy across decades.

This aspect of his career matters for two reasons. First, it places Brathwaite inside a lineage of photographer-historians of Black music—figures who understood that the sound was not separate from the politics. Jazz, soul, reggae, and live performance have long served as public forums where Black modernity announces itself. Brathwaite photographed that announcement as it happened.

Second, it clarifies his skill: low light, fast-moving subjects, the pressure of unrepeatable moments. The beauty of his fashion portraits can make his documentary command easier to overlook, but the broader record shows a photographer who could work in nightclubs and arenas and still produce images that feel intimate rather than merely observational.

That intimacy is part of why his photographs do not feel like extractive journalism. He is rarely “discovering” Harlem; he is inside it. Even when he travels—across the African continent, across global Black events—his eye carries that same premise: the subject is not a curiosity. The subject is kin.

Pan-African travel and the diaspora as assignment

Brathwaite’s work is often anchored in Harlem in popular memory, but the best accounts of his life insist on his international reach. The New York Times obituary (as referenced in gallery repostings of the Times piece) describes him traveling to report on Pan-African unity and photographing abroad as part of a wider political commitment.

Aperture’s historical essays, along with later journalistic remembrances, place him in a network of Black internationalism: traveling, encountering activists, documenting cultural events beyond the U.S. The significance here is not simply that he had stamps in his passport. It is that he treated Black life as a global continuum at a time when American media systems often framed Black Americans as a domestic “issue,” cut off from the rest of the diaspora.

His photographs from these journeys, and the stories attached to them—documenting major cultural and political moments—expand the meaning of “Black Is Beautiful” beyond personal appearance. Beauty becomes a worldview: Black life as worth recording everywhere it exists, Black sovereignty as a legitimate aspiration, Black modernity as something that does not need white translation.

Why the canon arrived late

One of the persistent questions in Brathwaite’s story is why his recognition, in mainstream art institutions, arrived so late. The work existed. The impact existed. The slogan existed in public language. Yet for decades, Brathwaite’s name functioned as a kind of insider knowledge—known in Harlem cultural circles, present in Black publications, but not consistently elevated by the museums and major art presses that shape the official canon.

Aperture’s own framing of his monograph—published in 2019 and described as the first ever dedicated to his career—casts him as “under-recognized,” a key figure whose centrality had not been matched by institutional attention. The touring exhibition that followed, organized by Aperture and the Brathwaite Archive, was repeatedly described as the first major show to center him, and it moved through major venues in Los Angeles, San Francisco, Columbia (South Carolina), Austin, Detroit, Winston-Salem, and New York.

The delay is instructive, not incidental. It reflects the broader pattern of how Black cultural labor is often categorized: as “community” work rather than fine art; as ephemera rather than archive; as activism rather than aesthetic innovation. Brathwaite’s photographs complicated those categories. They were beautiful enough for fashion, political enough for history, intimate enough for family memory, and composed enough for museums. Institutions that prefer clean boxes did not always know what to do with a photographer whose primary audience was his own people.

MoMA’s tribute, written after his death, frames him as inventive and entrepreneurial, suggesting that his practice always combined art with self-sustaining structures. That combination is often precisely what the mainstream undervalues—until, suddenly, it does not.

The archive as a family project—and as a public fight

The recent resurgence of Brathwaite’s reputation is inseparable from the work of the Kwame Brathwaite Archive and his family’s insistence that the images be preserved, organized, and made available to the institutions that had previously overlooked them. This is a familiar dynamic in Black cultural history: families and local communities do the long stewardship, then museums arrive later to “discover” what was never lost.

In Brathwaite’s case, that stewardship has extended into film. A documentary—Black Is Beautiful: The Kwame Brathwaite Story—has been positioned as a major public retelling, with festival screenings and prominent interviews, and The Guardian’s review presents the film as both tribute and correction: a narrative that insists Brathwaite was “game-changing” and that his influence was wider than mainstream awareness admitted. Ebony’s coverage of the documentary similarly frames it as an unveiling of an “untold” story, emphasizing how Brathwaite’s work shaped Black cultural self-presentation.

It is worth pausing on the word “untold.” The story was told—within Harlem, within Black art and music circles, within the communities who recognized the Grandassa images as their own. What the documentary and the late museum attention are doing is translating that knowledge into mainstream cultural authority.

That translation raises ethical questions about archives that are not abstract. Who gets to own the narrative of Black visual history? Who gets to profit from it? Who gets to decide which photographs become “icons” and which remain community property?

These questions are not unique to Brathwaite, but his life makes them hard to ignore, because he was explicitly a community organizer. “Keeper of the Images” is not a neutral title. It implies responsibility—an ethic that images can be mishandled, miscontextualized, or extracted.

If you want a parallel from a different domain, consider how watchdog organizations like Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington (CREW) have pursued legal fights over government record preservation and public access—arguing, in effect, that records are a form of power and that losing them reshapes what the public can know. Brathwaite’s stakes were cultural rather than bureaucratic, but the logic is analogous: what gets kept determines what can be proven; what gets lost determines what can be denied.

The meaning of “Black Is Beautiful” after it became a brand

One of the most complicated parts of Brathwaite’s legacy is that his central slogan outgrew its origins and became a commodity. By the 1970s and beyond, “Black is beautiful” could be invoked to sell products as easily as to sell dignity. The phrase’s mainstream spread is a testament to Brathwaite’s success—and also a warning about what happens when radical aesthetics become market language.

Brathwaite’s photographs help us recover the slogan’s original texture. In his work, “Black is beautiful” is not a feel-good caption; it is a corrective to a sustained visual assault. It is a refusal of the idea that Black women must approximate whiteness to be seen as elegant. It is a refusal of the idea that Black neighborhoods are only newsworthy when they are in crisis. It is a refusal of the idea that Black culture requires white endorsement to count as culture.

When contemporary fashion houses cite the era, or when pop culture redistributes the imagery, the question becomes whether the citation returns to that original refusal—or simply borrows the style while skipping the politics. The Root’s discussion of how Brathwaite’s work influenced a major contemporary fashion campaign underscores the ongoing pull of his imagery in modern branding, even as it gestures back toward the movement roots.

The point is not to scold cultural borrowing; Brathwaite himself understood circulation. The point is to insist that circulation without context can turn history into mood, and mood into product.

What Brathwaite’s images teach about representation now

It is tempting to treat Brathwaite as a “then” story: the 1960s, the Black Arts movement, the era of slogans and natural hair politics. But the endurance of his work suggests something else: he photographed a conflict that is still ongoing, though it now wears different clothes.

Representation remains contested. The rules have shifted—social media allows self-publication, cameras are ubiquitous—but the underlying pressures persist: which faces are considered “universal,” which aesthetics are labeled “professional,” which histories are canon, which are niche. Brathwaite’s photographs are a training manual for resisting those pressures without waiting for permission.

They are also a reminder that representation is not purely symbolic. When the Grandassa Models stepped onstage, they were not only modeling clothes; they were modeling an interior shift—Black women permitted to feel themselves as central. When Brathwaite photographed everyday Harlem life with the same seriousness he gave to celebrities, he was building a democracy of attention: ordinary Black people worthy of the archive.

This is why museums now return to him not simply as an historical figure, but as a contemporary resource. The Studio Museum in Harlem’s presentation of his work frames him as both photojournalist and community organizer—an artist whose practice cannot be separated from the neighborhood’s cultural life. The National Gallery of Art positions him within a larger story of cultural production and Black arts organizing.

The institutions are, in effect, conceding what Harlem always knew: he did not merely record a movement. He made its look.

Death, remembrance, and the late arrival of flowers

Brathwaite died at 85 in April 2023, with multiple outlets noting the announcement by his son and the growing public recognition of his contributions. The remembrance cycle that followed—tributes, museum essays, renewed attention to the archive—illustrated the familiar American pattern of belated appreciation, especially for Black cultural pioneers whose work was deemed too “local” or too “activist” to be immediately canonized.

But there is something slightly different here, too: Brathwaite lived long enough to see much of the recognition begin. The 2019 monograph, the touring exhibition, major museum presentations, the steady growth of press around the work—these were not posthumous miracles. They were, at least in part, the result of sustained advocacy while he was still here.

That matters because it reframes him not as a tragic “lost” figure but as a strategist of legacy. “Keeper of the Images” can be read, finally, as self-description: a man who understood that photographs are vulnerable, that archives need guardians, that Black history can disappear in plain sight if it is not defended.

Brathwaite and the KOLUMN conversation

KOLUMN Magazine has recently been building a sustained editorial meditation on Black art, Black institutions, and Black self-making—stories that treat culture not as decoration but as infrastructure. Its essay on James Van Der Zee, for example, argues that the photographer created a visual language of Black aspiration that still instructs how we read Harlem and dignity. Another recent KOLUMN feature on the Studio Museum in Harlem frames the museum’s reopening as a homecoming and a recommitment to Harlem as a site where Black art “lives,” not as trend but as core American narrative.

Brathwaite belongs in that conversation as both bridge and engine. Like Van Der Zee, he understood the portrait as collaborative self-definition. Like the Studio Museum’s mission insists, he treated Black art as central—not as supplemental to American culture but as one of its primary authors.

What differentiates him is the explicitness of his challenge. Van Der Zee photographed Black dignity in the face of racist caricature; Brathwaite photographed Black beauty in the face of racist beauty doctrine, and he did so with a movement infrastructure behind him. The camera, in his hands, was never only a camera. It was a megaphone made of light.

What it means to look at his photographs now

To look at Brathwaite’s Grandassa portraits today is to confront a paradox: the images feel timeless, yet their original context was urgently specific. The natural hair that now appears in corporate commercials once got Black women penalized at work and shamed in schools. The Afrocentric jewelry and garments now sold as “boho” once signaled a political alignment, a refusal to be styled by the West’s gaze.

Brathwaite’s gift was to photograph those refusals without photographing them as refusal. He photographed them as simply true: a woman is beautiful; a community is vivid; a neighborhood contains glamour and seriousness; Blackness is not a defect to be managed but a field of design.

That truth is why contemporary institutions continue to stage his exhibitions and why filmmakers continue to tell his story. But it is also why the work should not be outsourced to institutions alone. Brathwaite’s photographs began as community property. They were made to be seen by the people inside them.

And perhaps that is the final lesson: the most radical images are not always the ones that show violence. Sometimes they are the ones that show a Black woman, perfectly lit, looking back with the calm certainty that she does not need to be translated.

Suggested KOLUMN Magazine companion reading

Brathwaite’s story intersects directly with KOLUMN’s ongoing coverage of Black visual history, Harlem as cultural engine, and institutions that safeguard Black art:

KOLUMN Magazine’s “James Van Der Zee: The Photographer of Black Possibility” offers a parallel lineage of Harlem portraiture as self-definition and archive.

KOLUMN Magazine’s “Where Black Art Lives, Again” on the Studio Museum in Harlem’s return situates Harlem’s cultural institutions as infrastructure—precisely the kind of ecosystem Brathwaite worked within and expanded.

More great stories

The Case of Alberta Jones