Jackson’s presidential races sit at the intersection of movement and institution. They are the story of a preacher who believed politics could be a form of public ethics.

Jackson’s presidential races sit at the intersection of movement and institution. They are the story of a preacher who believed politics could be a form of public ethics.

By KOLUMN Magazine

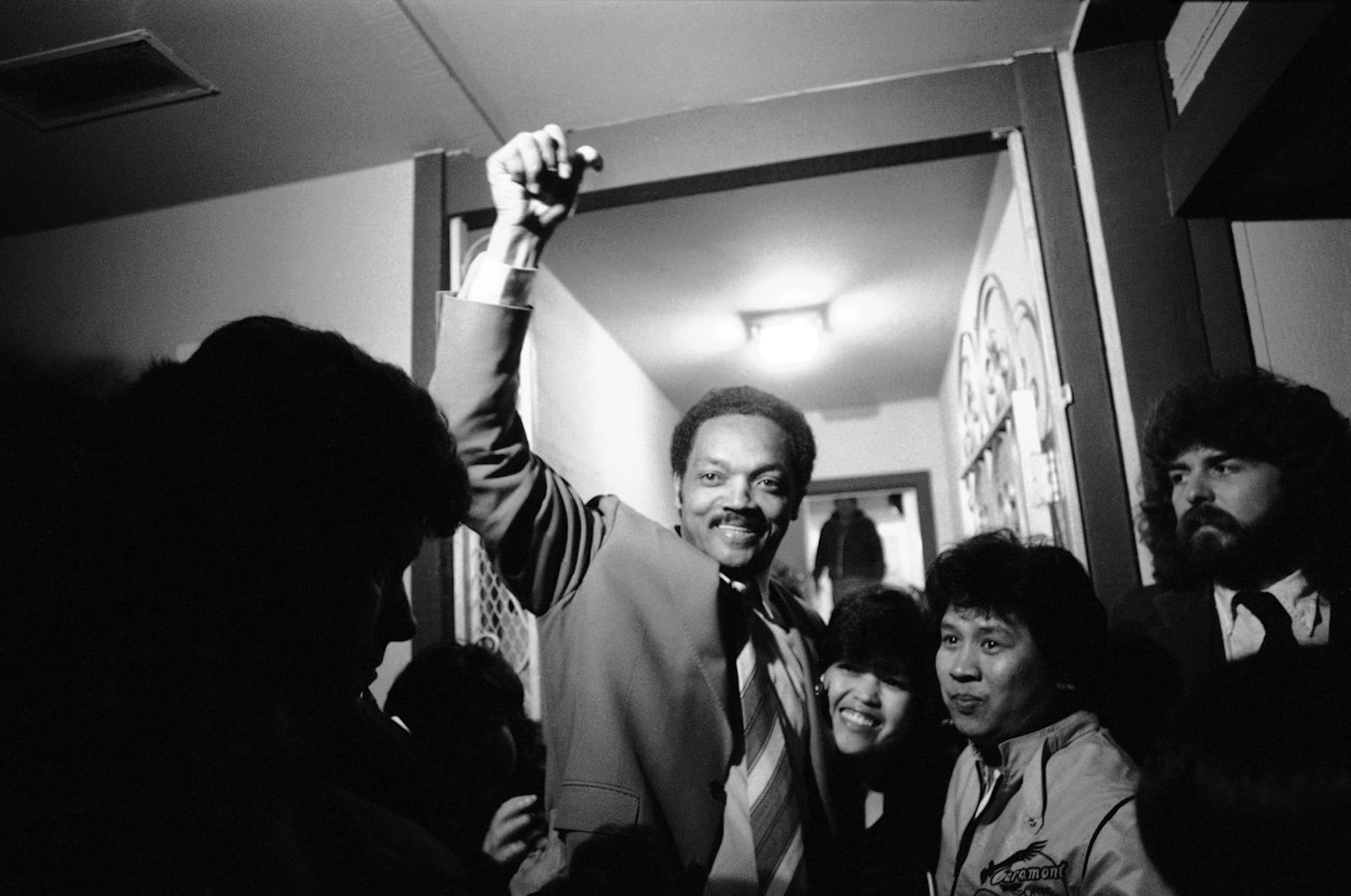

In the years when America was busy congratulating itself on the victories of the civil-rights era and settling into the hard certainties of the Reagan revolution, Jesse Jackson entered presidential politics with a proposition that sounded, at first, like a slogan and then, with repetition, like a theory of the nation. He called it the Rainbow Coalition: a multiracial, cross-class alliance of Black voters, Latinos, Asian Americans, Native people, union households, family farmers, the poor, peace activists, young people, and white progressives—groups that, in Jackson’s telling, were not separate constituencies fighting for scraps, but fragments of a majority that could govern if it learned to act like one. The idea, delivered with a preacher’s rhythm and an organizer’s impatience, was both moral and tactical: a demand for dignity and a plan for delegates.

Jackson ran for the Democratic presidential nomination in 1984 and again in 1988, and those two races—often reduced in shorthand to “historic but unsuccessful bids”—were, in fact, among the most consequential insurgent campaigns of late 20th-century American politics. They altered the language of Democratic coalition-building, expanded the imagination of Black electoral ambition, and helped define the pathways by which a party that had once treated civil-rights advocacy as both obligation and inconvenience would, by the end of the century, depend on a diverse electorate as its base. His campaigns produced a generation of organizers and operatives; they registered voters and made new political identities legible; they reshaped the conversation about economic justice and foreign policy; they also collided with the brutal physics of presidential nomination politics—calendar timing, regional gatekeepers, media narratives, donor capacity, and the persistent suspicion that a Black candidate could be “inspirational” without being “viable.”

What Jackson did not do is win. But presidential politics is not only the story of who becomes president. It is also the story of who gets to run without apology; whose issues become “national”; and which coalitions are considered normal rather than experimental. Jackson’s presidential races—especially 1988, when he briefly moved through the season not merely as a moral witness but as a contender—pressurized the Democratic Party’s internal contradictions in real time: race and class, ideology and electability, movement and machine. In forcing those tensions to the surface, Jackson changed the party that would later nominate and elect Bill Clinton, and, later still, Barack Obama.

This story is best told not as a single campaign narrative but as a political education in two acts, shaped by the same voice but different circumstances: 1984, when Jackson’s candidacy was treated as symbolic until it proved it could win; and 1988, when the symbol acquired infrastructure and the infrastructure produced a moment that startled the establishment.

The political weather of the early 1980s

By the time Jackson announced his first run, the Democratic Party was still recovering from the fractures of the 1970s and the landslide defeats that had taught party elites to fear “liberal” as an epithet and “left” as a diagnosis. Ronald Reagan’s ascendancy was not only electoral; it was ideological. The country’s default assumptions about government, taxes, unions, and social spending had shifted rightward, and Democrats were stuck in an argument about whether their survival required triangulation or a counter-story rooted in economic fairness.

Jackson was not, in that context, a conventional candidate. He was a civil-rights leader and minister, a national figure whose career had been built not inside the Democratic Party’s professional ladder but alongside it—pressuring corporations through Operation PUSH, mobilizing protests, negotiating with power from the outside. Obituaries and retrospective accounts emphasize how Jackson’s stature came from the civil-rights movement and his long campaign for racial and economic justice. But that outsider status was a liability in presidential politics, where donors, party leaders, and media institutions often reward familiarity and punish improvisation.

The irony is that Jackson was also, by temperament, a political insider’s dream: charismatic, disciplined in message, relentless in travel, and unusually fluent in the mechanics of coalition. His genius was not merely rhetorical—though his rhetoric could make even procedural politics sound like prophecy—but organizational. His belief was that the Democratic Party’s future depended on expanding participation, not narrowing it; on registering and mobilizing voters who had been treated as peripheral; and on connecting racial justice to pocketbook politics in a way that made moral claims actionable.

1984: The “symbolic” campaign that started winning

Jackson’s 1984 campaign began under the shadow of a presumption: that it existed to make a point, not to win. Even sympathetic Democrats described his run as a “message” candidacy. Yet 1984 quickly became a lesson in how message campaigns can become delegate campaigns once they demonstrate measurable strength. Jackson ultimately secured 3.28 million primary votes—about 18.2%—and won contests including Louisiana, the District of Columbia, South Carolina, Virginia, and a Mississippi contest, becoming the first Black candidate to win a major-party state primary or caucus.

Those numbers mattered for more than pride. They created bargaining power within a party whose nomination rules and delegate allocation had long been shaped by factions with better access to money and institutional support. Jackson’s campaign argued, explicitly, that Democratic rules had minimized the impact of his voters in 1984 and should be reformed to better reflect popular support—a critique that would echo in later nomination fights across decades. In 1985, Jackson pressed party rules officials for changes that would award delegates more proportionally to the vote, framing the issue as democratic fairness rather than inside baseball.

To tell the story only through delegate math, though, misses what his 1984 run did culturally. Jackson’s campaign made the language of “coalition” concrete. In his convention speech—the Rainbow Coalition address—he insisted that America’s pluralism was not a weakness to manage but a strength to organize. In the speech’s most enduring passages, he sought to bind constituencies not by flattening their differences but by translating them into mutual interest: the farmer and the worker, the immigrant and the laid-off industrial employee, the Black voter and the white progressive, the marginalized and the newly precarious. The message was aspirational, but it was also a strategy: a way to build a majority in a party that had increasingly become a federation of interest groups without a unifying story.

Jackson also carried controversies that revealed the unforgiving standards applied to insurgent candidates, especially Black candidates, operating within a media environment eager for missteps. Those controversies—some rooted in real harm, some inflated by opponents—became part of the public’s introduction to the idea of Jackson as a national politician rather than a movement leader. The point here is not to relitigate every episode, but to recognize a pattern that would recur: Jackson’s candidacy forced Americans to decide whether they would treat a Black candidate as a full political actor, subject to scrutiny and capable of error, or as a symbol who must remain pure to remain acceptable. The latter is not a standard applied to most white candidates.

If 1984 established Jackson’s legitimacy, it also revealed the limits of a campaign that, by his own supporters’ accounts, was under-resourced and often treated as a crusade rather than a professionalized operation. Retrospectives from the period and later analyses describe the campaign’s evolving sophistication—and the ways it was still learning, in public, how to compete in a nomination system built for candidates who arrive with money, endorsements, and party infrastructure already in place.

Even so, by the end of 1984, Jackson had done something that seems obvious only in hindsight: he proved that a Black candidate could win primaries, shape the platform conversation, and command national attention without being dismissed as a novelty. And then he did what most insurgents struggle to do after the campaign ends: he tried to turn the campaign into a durable movement.

Between the races: Building an apparatus, not just a moment

Jackson’s second run cannot be understood without the work between 1984 and 1988. The Rainbow Coalition was not simply a campaign brand; it became organizational infrastructure, inspiring state and local entities that attempted to translate Jackson’s national message into year-round organizing. One example, documented by the University of Washington’s civil-rights and labor history project, describes how activists in Washington State formed a Rainbow Coalition inspired by Jackson’s 1984 campaign, aiming for a progressive, multiracial alliance outside traditional mainstream electoral politics.

This period also sharpened the substance of Jackson’s platform. He was developing a governing critique of Reagan-era economics—jobs, infrastructure, labor rights, social welfare, education—while also asserting foreign-policy positions that were unusual for a domestic movement leader: skepticism of militarism, attention to the Global South, and a willingness to treat diplomacy as a moral act rather than a technocratic specialty. Dr. James Zogby of the Arab American Institute, reflecting on Jackson’s campaigns, has argued that Jackson injected perspectives on foreign policy debates that were distinct in their emphasis on human rights and international solidarity.

Meanwhile, the party environment was changing. Democrats had reason to believe Reaganism was not invincible; scandals and political shifts suggested opportunity. The Atlantic’s late-1980s political reporting captured a Democratic field and party trying to price the value of the 1988 nomination and to reconcile old party faith—equity and compassion—with the realities of the Reagan revolution. Jackson, in that reporting, is framed as part of the faction that could turn conventions into revival meetings, the preacher of the old-time religion of Democratic ideals.

Jackson was still seen by many analysts as an unlikely nominee. But “unlikely” is not the same as irrelevant. By 1988, he returned to the race with greater financing, better organization, and a constituency that had learned, from the first run, how to translate moral enthusiasm into turnout.

1988: When “message” became “front-runner,” briefly and loudly

The 1988 Democratic primary field was crowded and, in some ways, emblematic of the party’s identity crisis: establishment figures, technocratic reformers, regional candidates, and future national leaders in their earlier forms. Jackson entered as both a familiar insurgent and an improved candidate. His chant and slogan—“Keep Hope Alive”—wasn’t merely branding; it functioned as an emotional architecture for a coalition that understood itself as locked out of full belonging but unwilling to concede the future.

By March 1988, Jackson’s campaign began producing results that even skeptics had to incorporate into their models. The Washington Post’s contemporaneous reporting captured the shock of seeing Jackson atop certain measures of the “scoreboard,” including popular votes won in primaries at that point in the race, even as the delegate math remained complex and the obstacles ahead daunting.

He was also expanding his support beyond the boundaries that critics insisted would confine him. Reporting from the South described how some white politicians endorsed him and how his coalition included unemployed workers, farmers, union laborers—people who did not fit the caricature of Jackson as a “one-race” candidate.

And then came Michigan.

In late March, Jackson won the Michigan Democratic caucus decisively—an outcome widely treated as a jolt to the nomination narrative because it demonstrated his ability to win outside the South and outside overwhelmingly Black electorates. Later commentary and political essays have described that Michigan moment as one in which Jackson briefly appeared not only viable but, by certain measures, leading. The Nation, reflecting on the legacy of the Rainbow Coalition, would later describe how Jackson’s 1988 campaign “rocked the political establishment” when he won Michigan and temporarily took the lead for the nomination.

Mainstream coverage at the time captured the whiplash. TIME magazine, in an April 1988 piece, framed Jackson as having seized the crown of Democratic front-runner—for the moment—turning the Rainbow Coalition into something that looked “real, not rhetoric.”

That “for the moment” matters. The Democratic nomination system is less forgiving to insurgents than the phrase “front-runner” implies. Calendar sequencing, regional clustering, media framing, and resource disparities can combine to create a campaign that surges and then stalls. After Michigan, Jackson needed to consolidate across states where he was still treated as an ideological candidate, or a symbolic one, rather than as a plausible general-election nominee. The uphill climb was steep: establishment leaders, donors, and influential constituencies in the party were coalescing around Michael Dukakis, whose candidacy promised competence and a kind of managerial liberalism that many believed would better neutralize Republican attacks.

Yet even as Dukakis emerged as the eventual nominee, Jackson’s near-run to the top of the heap forced Democrats to confront their own coalition’s internal hierarchy. Jackson and Dukakis’s relationship became a story in itself—negotiations, tensions, and questions about what Jackson’s supporters would demand in exchange for unity. Accounts of the period emphasize the struggle over unity and the jockeying for influence that followed, reflecting a reality of coalition politics: if you bring voters, you ask for power.

Jackson ended 1988 with a larger vote total than in 1984 and a broader set of wins, including contests in the South and elsewhere, demonstrating that his coalition could travel. The significance is not that he lost to Dukakis; it is that the loss occurred after Jackson had demonstrated that the party’s base was becoming more diverse, more urban, and more attuned to economic inequality—and that a candidate who spoke that language could build a serious campaign.

The hard parts: Criticism, controversy, and the limits of charisma

Any honest accounting of Jackson’s presidential races must include not only the poetry but the friction. Jackson’s strengths—charisma, media magnetism, moral certainty—were sometimes inseparable from traits that critics experienced as self-centeredness or tactical opportunism. Some Black activists and progressive organizers questioned whether the Rainbow Coalition was as “organic” as its rhetoric suggested, or whether Jackson’s national profile occasionally overshadowed grassroots movements that had been doing the slow work long before the cameras arrived. (These critiques show up repeatedly in later left analyses of the era.)

There were also real-world operational problems: fundraising pressures, organizational gaps, and the constant burden of sustaining a national campaign that was both electoral and movement-based. The Washington Post reported on the strains of raising money and maintaining discipline in 1984, a reminder that insurgent candidates are often asked to run both against their opponents and against the structural disadvantages of their outsider status.

Campaigns also exist within legal and ethical frameworks that can become vulnerabilities. The Federal Election Commission’s records include a case involving an unauthorized political committee, “Americans for Jesse Jackson,” which resulted in a consent order addressing violations of campaign finance law—an example of how the ecosystem around a campaign can create compliance problems even when the candidate’s authorized committee is not the only entity in play. This is part of a broader reality that good-government organizations have long emphasized: campaign finance enforcement is uneven, complicated, and often dependent on oversight systems that struggle to keep up with political innovation.

To include these details is not to diminish Jackson’s accomplishments; it is to treat his campaigns as what they were: real campaigns, with real stakes, operating in the same messy world as every other presidential effort. The mythologizing of “historic firsts” can flatten the human complexity that actually made those firsts hard.

What Jackson changed inside the Democratic Party

If you measure political significance only by office-holding, Jackson’s presidential races are footnotes. If you measure by what becomes possible afterward, they look more like a hinge.

One clear impact was voter activation. Later analyses and scholarship have argued that Jackson’s candidacies helped shift Black political behavior more firmly into electoral participation as a strategy for policy change, supplementing protest politics rather than replacing it. The Atlantic, drawing on political science work, has described how Jackson’s 1984 and 1988 candidacies “activated” African Americans to identify and support leaders who could advance Black political aims through elected office—part of a broader shift from protest to formal politics.

Another impact was personnel. Presidential campaigns are training grounds. Jackson’s operations—especially in 1988—helped cultivate organizers, policy thinkers, and political professionals who carried the lessons of coalition politics into later Democratic work. This is the kind of legacy that does not show up on election night charts but shows up for decades in who runs city agencies, who staffs campaigns, who builds turnout operations, and who teaches the next generation how to count power.

A third impact was ideological. Jackson insisted that economic justice and racial justice were not separate planks but a single structure. He spoke about jobs programs, infrastructure investment, education funding, labor rights, and anti-poverty efforts as integral to a moral democracy. Later commentary has traced how Jackson’s synthesis of labor politics and racial equality functioned as a kind of “political revolution,” one that offered a left-populist alternative to both Reaganism and the Democratic Party’s emerging centrist instincts.

And then there was language—arguably Jackson’s most durable instrument. “Keep Hope Alive” became more than a campaign motto; it became a communal phrase, invoked in Black political life as both encouragement and insistence. Ebony’s coverage of Jackson, including later reflections on his slogan and legacy, signals how deeply that phrase lodged in cultural memory.

What Jackson made possible, without claiming he did it alone

It is tempting, in retrospect, to treat Jackson as a direct line to Obama: Jackson ran so Obama could win. That story is emotionally satisfying and partly true, but too neat. What Jackson did was widen the realm of plausibility. He made it harder for party elites and mainstream media to claim that a Black presidential contender was inherently nonviable. He also demonstrated the importance of building coalitions that did not treat Black voters as a moral constituency to be courted once every four years but as a base with agenda-setting authority.

PBS NewsHour, in a segment on Jackson’s political legacy connected to the book A Dream Deferred, emphasizes his role in reshaping the Democratic Party and registering millions of voters—an institutional impact that outlasts any single campaign.

Still, Jackson’s campaigns also reveal that coalition politics is fragile. The Rainbow Coalition was both inspiring and difficult: a project of translation across race, geography, ideology, and economic interest. It required persuading voters that their specific struggles were not in competition, and persuading party leadership that these voters were not optional. The coalition’s success depended on constant organizing—and its limits were exposed whenever electoral incentives encouraged candidates to segment the electorate rather than unify it.

The deeper significance: The campaigns as a test of American democracy

There is a reason Jackson’s presidential races remain resonant even decades later. They posed questions that have not gone away.

What does it mean to be represented? Jackson argued that representation was not merely demographic; it was agenda-based. A Black candidate was not significant only because of race, but because of what that candidacy could do to force neglected issues—poverty, deindustrialization, labor power, farm crisis, mass incarceration’s early architecture, unequal schooling—into the center of political conversation.

What does coalition mean beyond election season? Jackson’s critics often implied that the Rainbow Coalition was rhetorical. But the lasting evidence suggests it was also practical: it seeded organizations, inspired state coalitions, and provided a blueprint—imperfect, contested, but real—for how to build multiracial progressive power.

What does “electability” actually measure? In both 1984 and 1988, Jackson confronted a familiar logic: that the country was not ready, and therefore the party must not try. Yet readiness is not an objective fact; it is often the result of choices made by party leaders, donors, media institutions, and voters. Jackson’s campaigns showed that “not ready” can be a way of protecting the status quo—and that campaigns can, by existing and competing, help make readiness.

And what does democratic participation require? Jackson’s emphasis on voter registration and mobilization anticipated later debates about turnout politics versus persuasion politics. If you believe the electorate is fixed, you tailor your message to the median voter. If you believe the electorate can expand, you invest in people who have been ignored. Jackson chose the latter. That strategic choice—treating marginalized citizens as potential majorities—has become a central axis of modern Democratic politics.

After the races: How a “loss” becomes a template

After 1988, Jackson did not vanish; he remained a major figure, sometimes as a broker, sometimes as a critic, sometimes as a symbol of a style of politics that the party would alternately embrace and keep at arm’s length. Obituaries published on February 17, 2026, following his death at 84, underline the consensus view that Jackson’s presidential campaigns were groundbreaking and that they helped pave the way for future Black candidates, even as they note the controversies and complexities that accompanied his public life.

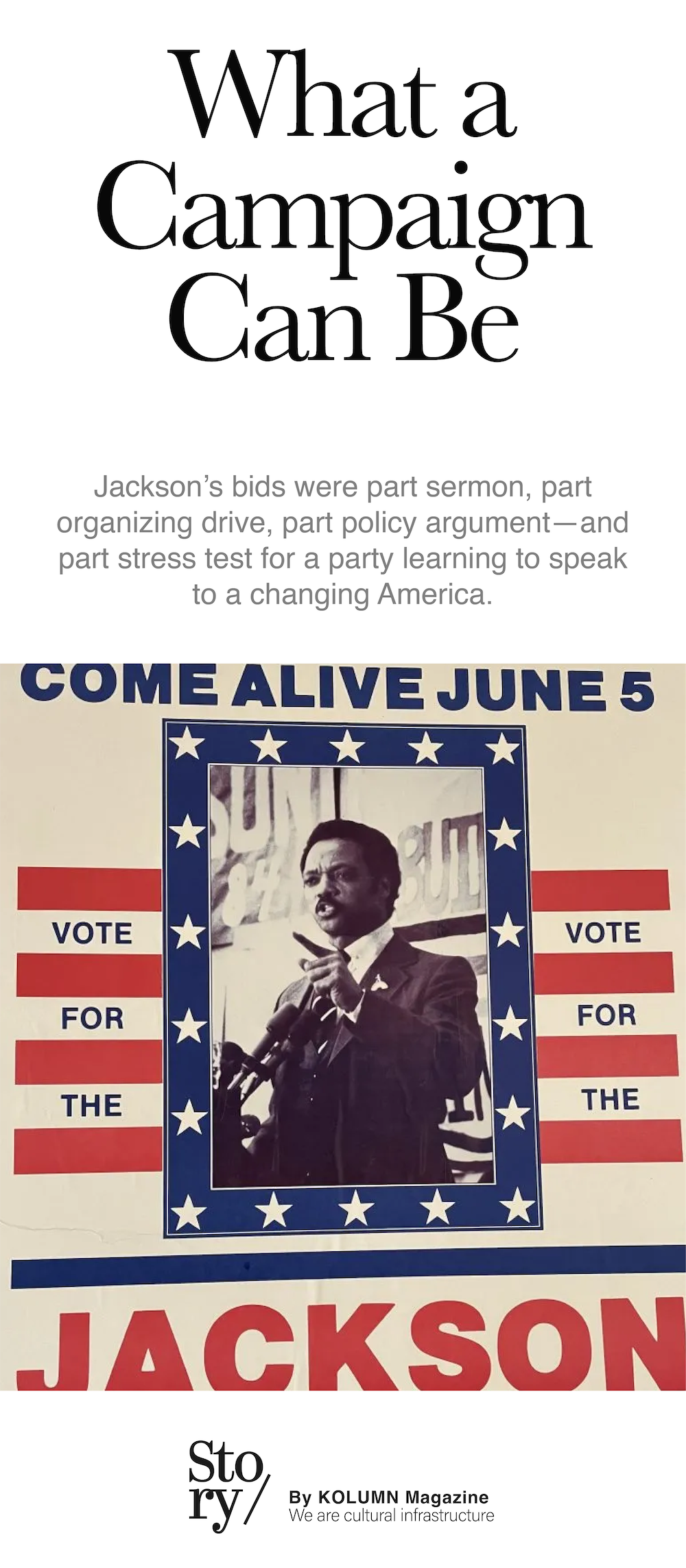

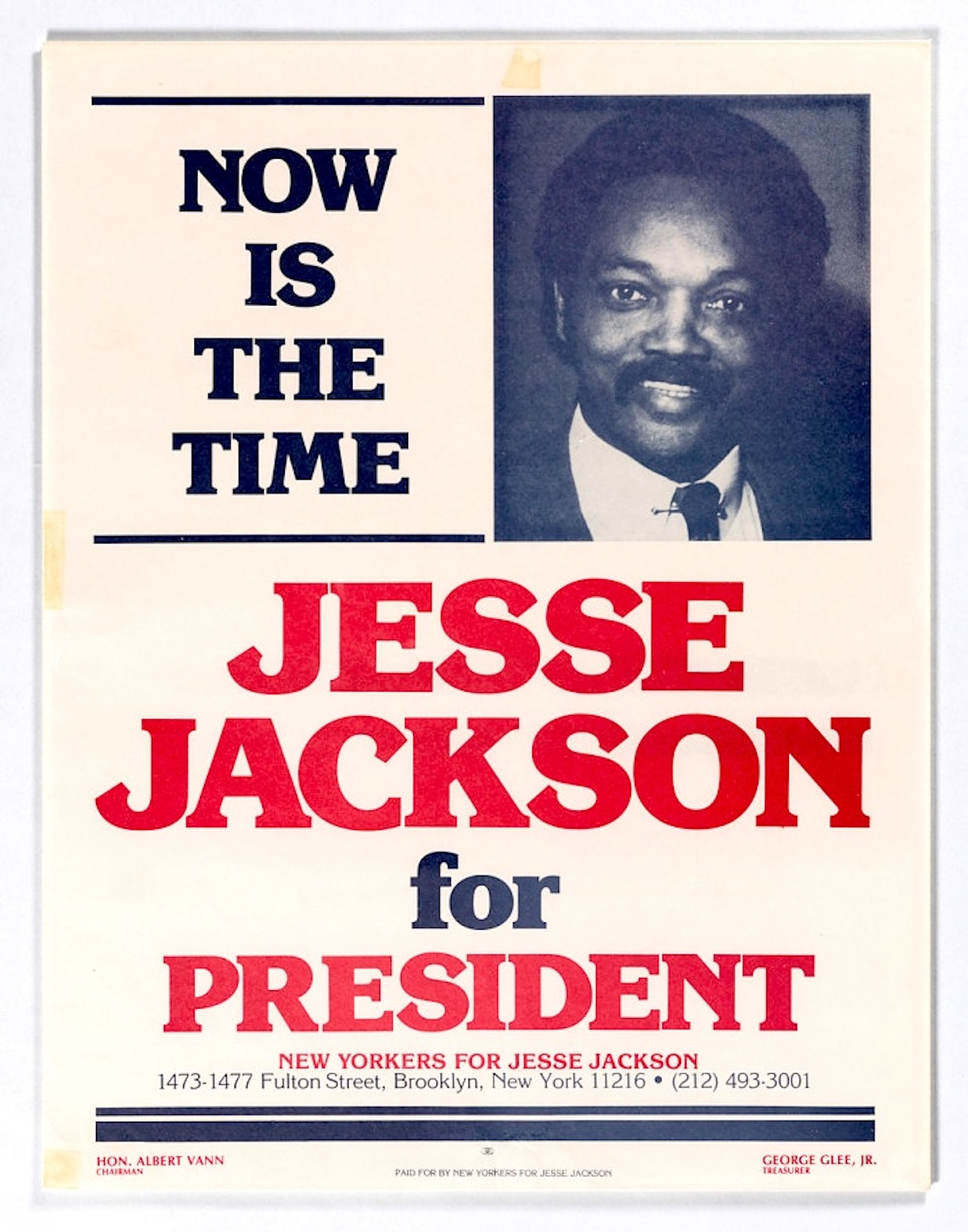

In a narrower sense, Jackson’s campaigns also left artifacts that continue to circulate: his speeches, his slogan, and even the graphic design of campaign materials that later reappeared as cultural memorabilia—a reminder that presidential runs imprint themselves not only on policy but on aesthetics and identity.

But the more meaningful artifact is procedural and psychological: the understanding that insurgent campaigns can shift a party’s center of gravity even when they do not win. That lesson would be relearned in later decades—by candidates on the left who used presidential primaries as organizing vehicles, and by candidates from marginalized backgrounds who insisted that their presence was not symbolic, but structural.

Jackson’s presidential races sit at the intersection of movement and institution. They are the story of a preacher who believed politics could be a form of public ethics; an organizer who understood that ethics without organization becomes performance; and a candidate who proved that winning is not the only measure of power. The nominations went to Mondale and Dukakis. But the party—and the country those campaigns addressed—did not return to its earlier shape.

More great stories

The Camera as Citizenship