Cleaver has spent a lifetime insisting that Black political life is not a series of eruptions but a long argument with the nation.

Cleaver has spent a lifetime insisting that Black political life is not a series of eruptions but a long argument with the nation.

By KOLUMN Magazine

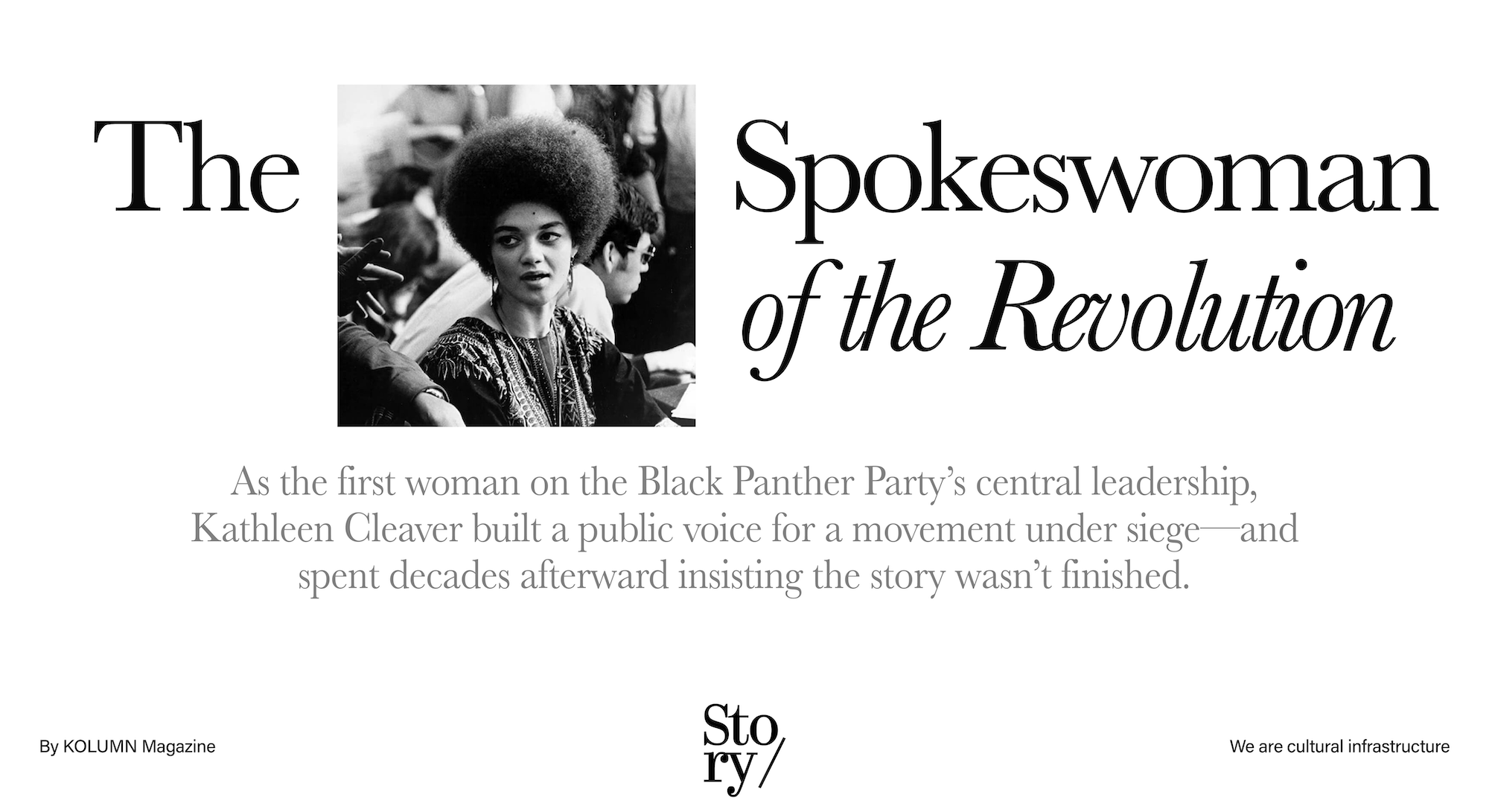

Kathleen Cleaver’s public life is often described as if it were a sequence of identities that replace one another: student, organizer, Black Panther, exile, mother, lawyer, professor. The neatness of that story is comforting—and misleading. Her biography reads less like a ladder than a braided rope, each strand tightening around the next: the discipline of movement work; the craft of public communication; the bruise of state repression; the insistence that Black history is not memory but record.

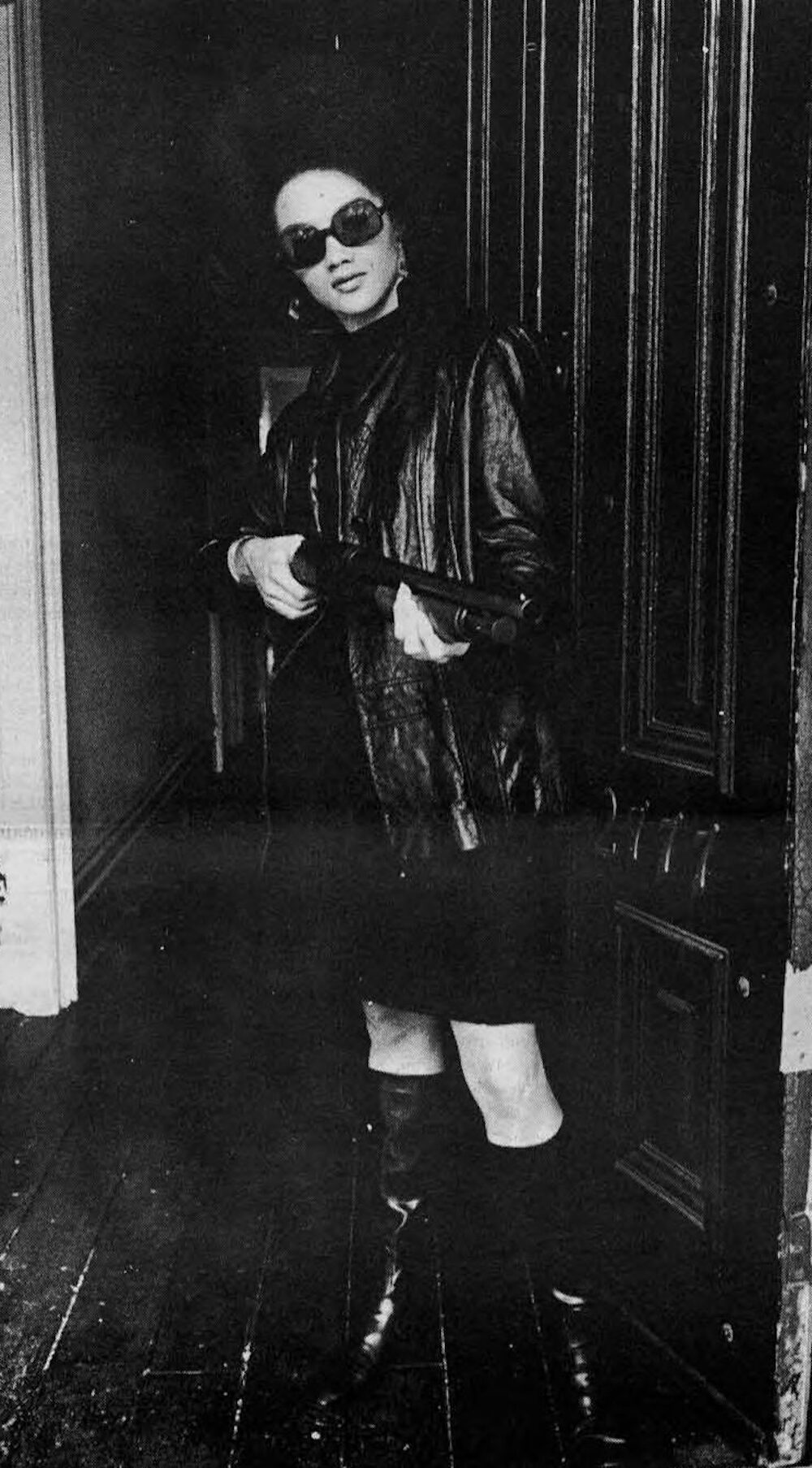

Cleaver became nationally visible as the communications secretary of the Black Panther Party (BPP), a role she helped define and then inhabited at a moment when the organization was being mythologized, infiltrated, prosecuted, and, in many cities, violently attacked. Her voice—calm, precise, sometimes cutting—moved across television studios and rally stages at a time when the Panthers’ image was being flattened into a single silhouette: the beret, the leather jacket, the rifle. She understood that the image could recruit, but it could also be used as a weapon against them. Her work was, in part, an argument with the country’s imagination about what Black radicalism meant and why it had emerged. In later decades, after the movement’s fractures and losses, she carried the same argument into law and academia, treating the past not as nostalgia but as an open file.

That file begins far from Oakland.

Cleaver was born Kathleen Neal in Dallas, Texas, in 1945, and she spent parts of her childhood in places that complicate the typical map of American civil-rights awakening—Tuskegee, yes, but also stretches of life abroad as her father worked in the U.S. Foreign Service, including time in India and the Philippines. The Library of Congress’s Civil Rights History Project interview notes those formative moves and her recollection of growing up across segregated America and overseas postings, a childhood that exposed her to competing political vocabularies and to the idea that “America” was not a single reality but a set of claims.

If Cleaver’s later work seems unusually attuned to how nations narrate themselves—how legitimacy is performed, how dissent is labeled—this early life offers one explanation. She had watched the United States from multiple distances: inside the long shadow of Southern segregation and from the vantage of other political cultures. The experience did not immunize her against American racism; it sharpened her sense of how power moves through institutions and stories.

By the mid-1960s, she was in the orbit of the civil-rights movement’s younger edge. She attended Barnard College but left before graduating to work with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), in the organization’s campus program. The decision placed her inside one of the era’s most consequential transformations: SNCC’s internal struggle over strategy, ideology, and the limits of liberal integrationism—an evolution that helped open the space in which “Black Power” would become both a slogan and a fault line.

In her oral-history interview, Cleaver describes that period with the kind of granular clarity that often comes only from proximity: the organizational labor, the debates, the feeling of a movement shifting under its own weight. SNCC taught her that politics was made not only in speeches and marches but in what she would later call the work of infrastructure—meetings, materials, networks, logistics, and the hard, unglamorous craft of persuasion.

It also taught her that the media environment was not neutral. Visibility could be both protection and trap.

In 1967, at a SNCC-related conference, she met Eldridge Cleaver, then the Black Panther Party’s minister of information and the author of Soul on Ice, whose essays had made him one of the era’s most recognizable—and polarizing—Black intellectuals. They married later that year. She moved to California and joined the Panthers, arriving as the party was becoming a national symbol and a national target.

The popular memory of the Black Panther Party often begins and ends with armed patrols and confrontations with police. That emphasis is not an accident; it was central to how authorities and many mainstream outlets framed the organization. But the Panthers also built survival programs—community breakfasts, health initiatives, education efforts—and they sought to place police brutality and poverty inside a broader analysis of American governance. Cleaver’s role sat at the intersection of those realities: she had to speak to the country about an organization that was doing social-service work while also declaring the legitimacy of armed self-defense in a state that had never hesitated to meet Black political assertion with violence.

As communications secretary, Cleaver functioned as spokesperson, press strategist, and political translator. The University of Texas School of Law notes her tenure from 1967 to 1971 and identifies her as the first woman to serve on the party’s Central Committee. The job required more than charisma. It demanded message discipline, speed, and an understanding that every public appearance could be converted into evidence—by the government, by hostile reporters, by frightened liberals, by rivals inside the movement.

She understood that the Panthers were fighting on two fronts: against the conditions they named—policing, poverty, war—and against a narrative regime that defined them before they could speak. In the Emory University announcement of its acquisition of Cleaver’s papers, her daughter, Joju, frames the archive as a corrective to amnesia and a reminder of how movements are co-opted and infiltrated, noting the Panthers’ experience with infiltration and distortion. That observation matches what historians have documented about COINTELPRO and other counterintelligence operations, but it also matches what Cleaver lived: the sense that the state was not merely reacting to the Panthers but actively shaping the conditions of their public existence.

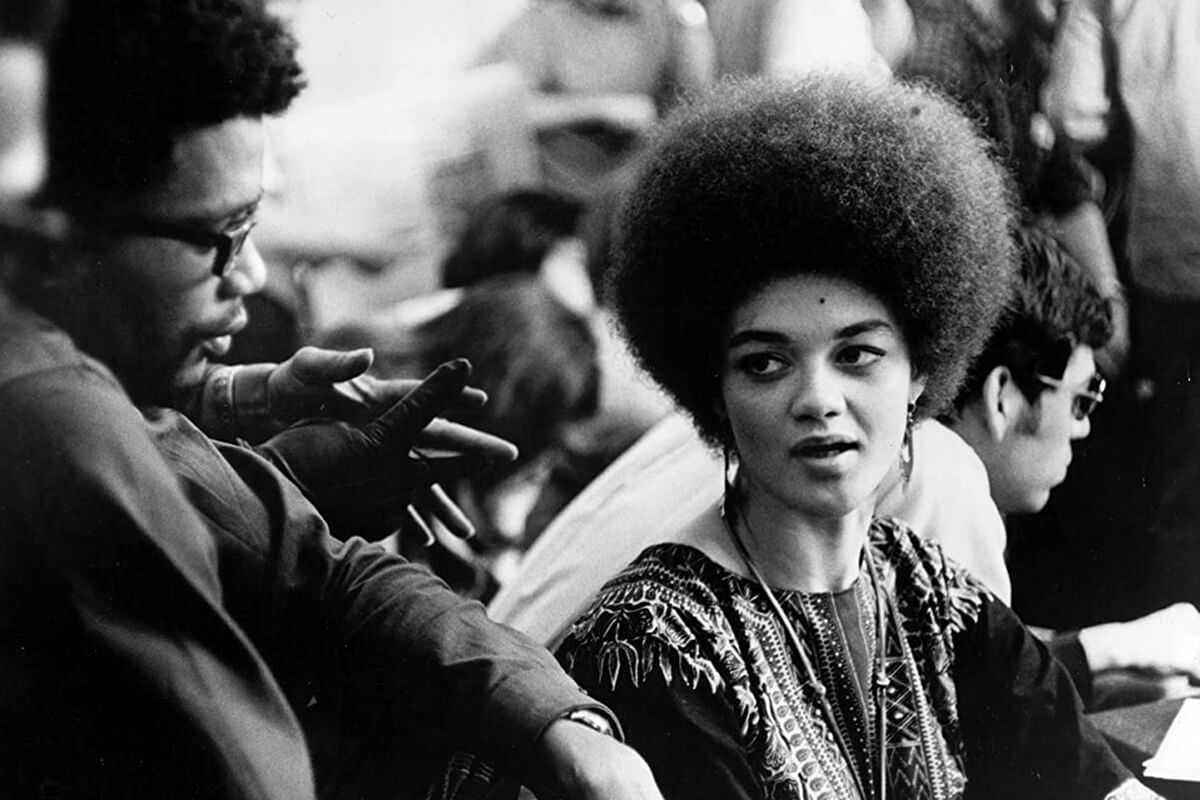

There is a scene that recurs in accounts of Cleaver’s time as a Panther: she is in front of microphones, answering questions that carry an accusation disguised as curiosity. Sometimes the questions are about violence; sometimes they are about her hair, her clothes, her presence as a woman in a movement stereotyped as male and militant. A later retelling in the socialist press captures the sharpness of one of her replies. Asked by a reporter what a woman’s place was “in the revolution,” she answered: “No one ever asks what a man’s place in the Revolution is.”

That line endures because it exposes the scaffolding of the question. It insists that gender is not a sidebar to political struggle but part of how the struggle is policed—by outsiders and, often, inside movements themselves. It also suggests something about Cleaver’s broader approach: she refused the premise when the premise was wrong. She corrected the frame.

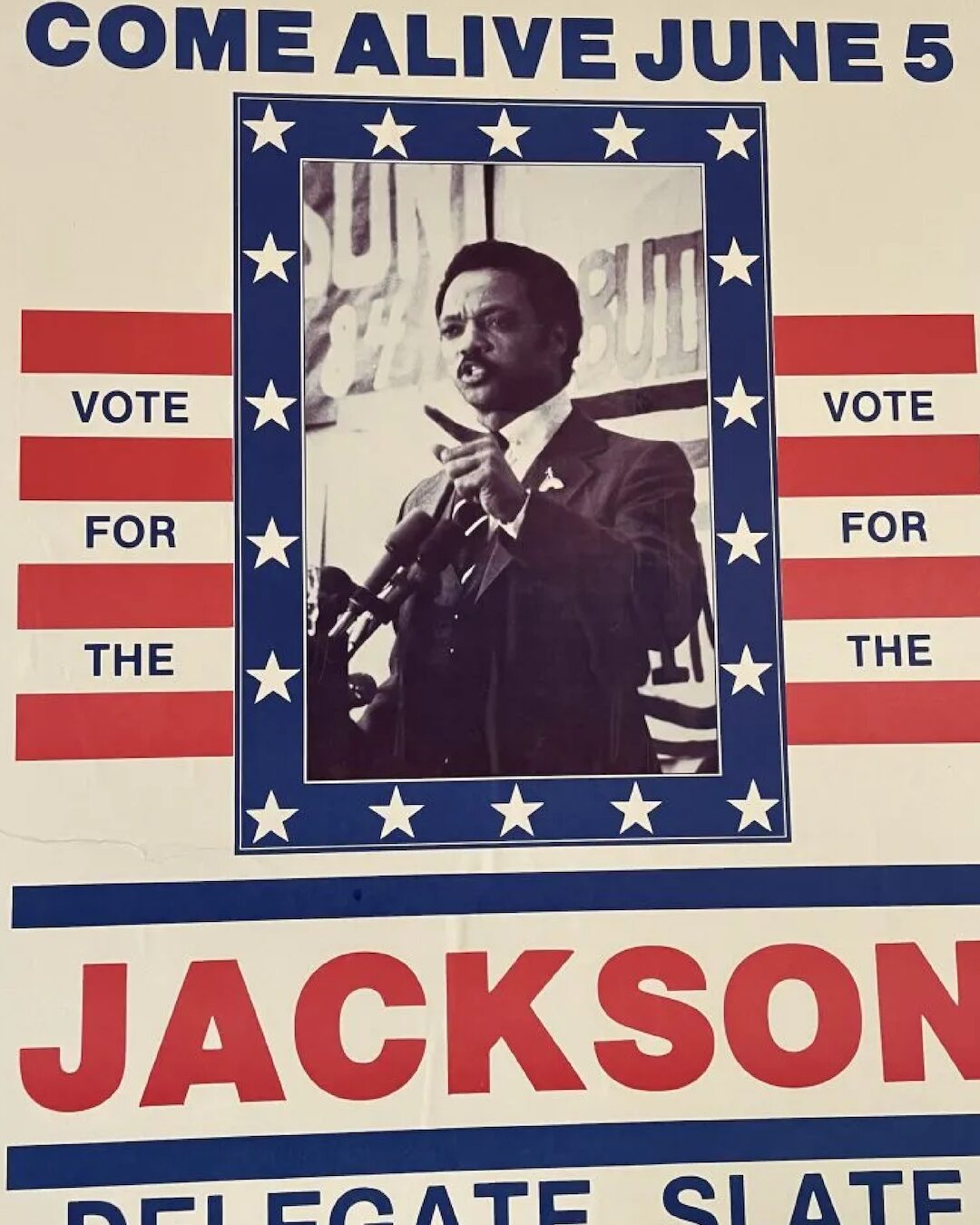

If the communications secretary’s work was to define the Panthers publicly, one of Cleaver’s most significant assignments was the “Free Huey” campaign—the national effort to win support for Huey P. Newton after he was arrested and charged in the killing of an Oakland police officer. She helped organize the kind of political theater that the Panthers understood could reshape public pressure: rallies, posters, press conferences, speeches that fused legal arguments with moral urgency.

The country remembers 1968 as an explosion—assassinations, uprisings, Vietnam, the Democratic National Convention, the widening crack in American legitimacy. For the Panthers, it was also a year of direct, escalating confrontation with law enforcement. Late that year, Eldridge Cleaver became involved in a shootout with Oakland police in which the teenage Panther Bobby Hutton was killed. Eldridge fled the country; Kathleen would follow into exile.

Exile is sometimes romanticized as a kind of revolutionary pilgrimage. In practice, it is often a bureaucratic and psychological grind: passports and surveillance, shifting alliances, financial instability, the strain of marriage under pressure, the constant calculation of risk. The National Archives’ profile notes that Kathleen joined Eldridge abroad after he fled in 1968, and that their lives moved through Cuba, Algeria, France, and other locations during those years. The story matters not because it is exotic, but because it forces a question the United States has never fully answered: what does it mean when political dissent becomes a reason to leave the country to survive?

In Algeria, the Cleavers’ home became part of a wider network of international revolutionary politics. The Panthers, like other Black Power organizations, increasingly positioned themselves within a global anti-imperialist frame. Cleaver would later describe the movement’s connections to other struggles and the sense—shared across the era’s radical left—that the United States’ domestic racial order was inseparable from its international posture.

But internationalism, too, had its costs. The practical conditions of exile—child-rearing, limited resources, internal conflicts—intersected with political strain. The relationship between Eldridge Cleaver and the Panthers’ Oakland leadership deteriorated. National governments shifted their tolerance. In the early 1970s, the family’s movements became increasingly precarious, with periods of separation and reconnection.

The most revealing exile accounts are often not the dramatic ones but the domestic ones: what it meant to be a young mother under the gaze of history, to be expected to symbolize revolution while maintaining a household, to live in places where you are simultaneously protected and watched. A resource compiled by the Indian Ocean History Project points to a Washington Post feature from 1970—“Wife, Mother and Revolutionary”—that offered an American readership a snapshot of Cleaver’s life in Algeria and the ways domesticity and politics were being braided in real time.

If the 1960s made Cleaver visible, the 1970s tested the endurance of that visibility.

When the Cleavers returned to the United States, they returned into the machinery of courts and probation, public controversy and private unraveling. The National Archives profile notes that Kathleen later returned to Yale University, finishing her undergraduate degree with honors in 1984, then earned a J.D. from Yale Law School, and eventually clerked in the U.S. Court of Appeals. Her pivot to law is often framed as a reinvention. It is more accurate to see it as a continuation: an organizer learning a new language of power.

Cleaver has said that watching the Watergate hearings influenced her interest in becoming a lawyer—an observation that also suggests her long-standing fascination with how institutions narrate wrongdoing and how procedure can either conceal or reveal the truth. The move into elite legal education has its own storybook resonance: the former revolutionary entering the citadel. But the point was never social ascent. It was access to tools.

After Yale, she worked in legal practice and then moved through academic and teaching roles, including at Emory University School of Law, where she became a senior lecturer. The Emory acquisition of her papers—correspondence, photographs, audiovisual materials—underscores that she has treated her life not only as lived experience but as an archive worth preserving for future analysis. In other words: she understands, perhaps better than most, that the fight over the Panthers has always been a fight over documentation.

That fight plays out in two competing American stories.

In one, the Panthers were a “gun-toting” extremist organization whose theatrical militancy frightened the public and justified aggressive law enforcement. In another, they were a disciplined community organization and political formation targeted for destruction because they exposed the violence embedded in American policing and governance. The Washington Post has traced that contested legacy across decades, noting both the sensational memory and the growing scholarly attention that treats the Panthers as more complex than their caricature.

Cleaver’s significance lies in how she complicates both narratives without flattening the realities that produced them. She does not ask the country to forget that the Panthers embraced militant imagery; she asks the country to remember why. She does not deny the organization’s internal contradictions; she insists that contradictions do not cancel legitimacy. In interviews, she has argued that the Panthers saw themselves as part of a revolutionary struggle, linked to other movements, and she has emphasized that their goals were not simply symbolic but structural: a different relationship between citizens and state power.

This is where Cleaver’s work as a communicator becomes inseparable from her later work as a legal thinker: she is always asking what counts as evidence and who gets to interpret it.

If the Panthers are remembered through photographs—Newton in the wicker chair, children at breakfast programs, members in formation—Cleaver is one of the figures who understood that photography itself is political. A public event at the American Academy in Berlin describes scholarship examining Cleaver’s “albums of exile” and the ways photography can be used to make “home” under displacement. This is not merely aesthetic interpretation. It echoes a core truth about political life: you live in the story you can keep.

The story Cleaver has tried to keep is one that includes women not as accessories but as architects. The Panthers, like many organizations of their era, had to confront sexism internally while fighting racism externally—a dual struggle that made women’s leadership both essential and contested. The Guardian’s writing on women in the Black Panther Party places Cleaver alongside figures such as Elaine Brown and Ericka Huggins and emphasizes women’s central role in building branches, sustaining operations, and surviving the state’s pressure. Cleaver’s own insistence on this point shows up not only in her quotes but in the arc of her career: she has repeatedly returned to the question of who is allowed to represent a movement.

That question has never been abstract. It shaped the Panthers’ lived conditions and, by extension, Cleaver’s.

The FBI’s counterintelligence operations targeted the Panthers with a blend of surveillance, infiltration, and efforts to provoke internal conflict—strategies that scholars and former members have described as designed not simply to prosecute crimes but to neutralize political capacity. The Emory archive announcement’s explicit reference to infiltration and distorted messaging, presented as a lesson for contemporary movements, reflects how central that experience remains to Cleaver’s understanding of political history.

In practice, that meant Cleaver’s job involved more than building support; it involved responding to an adversarial information ecosystem in which the state and media could collaborate—deliberately or inadvertently—to make radical politics appear illegitimate by definition.

She also had to navigate the movement’s internal tensions around leadership and visibility. Being the most recognizable female Panther leader was not simply a triumph; it created expectations and burdens. The public often treated her as a symbol: the glamorous revolutionary, the militant muse, the face framed by an Afro that itself became part of the era’s iconography. A Washington Post photo essay decades later would note how certain images—like the natural hair movement and “Black is Beautiful”—became political statements, and it specifically links a photographic project’s title to Cleaver’s comments about Black women loving themselves in their natural state.

This is another reason Cleaver’s life cannot be reduced to “activist turned professor.” She has spent decades arguing that culture is not decoration; it is political terrain.

If you want to understand Cleaver’s intellectual seriousness—how she thinks, not just what she symbolizes—you can hear it in long-form interviews rather than sound bites. In the PBS Frontline interview connected to “The Two Nations of Black America,” Cleaver discusses the Panthers’ revolutionary self-conception and the coalitional imagination that linked Black struggle to other oppressed groups and anti-imperialist movements. In the Library of Congress oral history, she narrates her path through SNCC, her observation of its dissolution, and her later organizing against police brutality—offering not mythology but lived chronology.

And in a 2015 interview with The Root, Cleaver reflects on the Panthers, the emergence of Black Lives Matter, and the afterlife of 20th-century radicalism in a 21st-century movement landscape. The point is not to stage a “then versus now” debate; it is to trace continuity and change. Cleaver’s generational position makes her a witness to the cyclical nature of American racial crisis: police violence prompting protest, protest prompting backlash, backlash prompting calls for “order,” and order functioning as a euphemism for existing hierarchies.

What changes is the platform. What persists is the contest over legitimacy.

The most common mistake in writing about Black Power figures is to treat their radicalism as temperament rather than analysis—as if people became Panthers because they were angry, not because they were observant. Cleaver’s biography disrupts that. She is not compelling merely because she was brave enough to be visible; she is compelling because she built the mechanisms of visibility with deliberation. She understood the media as a battlefield, and she fought on it with strategy.

That strategy is visible in the way she framed the Panthers’ goals. The Panthers used the language of self-defense, but they also used the language of governance: demanding community control, insisting that police brutality was not an “incident” but a structural problem, arguing that poverty was policy. Cleaver’s role was to articulate those arguments in public, where nuance was often punished. Her ability to keep the organization’s analysis in view—despite the noise of sensational coverage—helped shape how later historians and activists would understand the Panthers as more than their weapons.

It is also visible in her later editorial and scholarly work. She has contributed to books and essays that locate the Panthers within broader debates about race, feminism, and political theory, and she has remained engaged with questions of political imprisonment and civil liberties. Her professional life in law schools and lecture halls did not erase her movement identity; it translated it.

The translation matters because the American story of the Panthers is still unsettled.

For decades, mainstream portrayals oscillated between fear and fascination. But scholarship and cultural work have pushed back, asking what the Panthers’ “survival programs” meant in the context of state abandonment, and what it means that law enforcement treated community organizing as a threat. The Washington Post’s retrospective framing—recognizing the Panthers’ symbolic power while noting their contested legacy—captures this evolving interpretation. The Guardian’s photography features, which place Kathleen Cleaver inside archival images and exhibitions, show another shift: the Panthers as an object not only of political debate but of historical curation.

Cleaver sits at the center of that shift because her life contains both the movement and its afterlife. She is both subject and interpreter.

If there is a single throughline in her public work, it is a refusal to let the country turn complex political history into morality play. She does not offer the Panthers as saints. She does not accept the state’s claim that it was merely keeping order. She insists that Americans confront the conditions that made militant self-defense feel rational to a generation of Black youth—and confront the state’s willingness to treat Black political organization as an enemy force.

That insistence is, ultimately, what makes her important for readers beyond the era’s nostalgia. The United States is again living through a period in which protest and policing define the headlines, and in which movements are shaped by viral imagery, surveillance, infiltration fears, and internal ideological strain. Emory’s framing of Cleaver’s archive as “timely” because it provides context for contemporary movements is not academic marketing; it is a warning.

Cleaver’s lesson is not that today’s movements should copy the Panthers. It is that movements must understand how they are seen, how they are distorted, and how the record is kept. The story is not what you lived; it is what survives in the public file. Her life’s work suggests that the file is never neutral—and that building it is itself a form of struggle.

In the end, Kathleen Cleaver’s significance may rest less in any single role—communications secretary, lawyer, professor—than in the rare continuity between them. She has spent a lifetime insisting that Black political life is not a series of eruptions but a long argument with the nation: about violence and protection, democracy and exclusion, representation and truth. Her job, from the 1960s onward, has been to make that argument impossible to ignore.

More great stories

What a Campaign Can Be