Arthur P. Bedou's archive is a rebuke to the flattened images of Black life that dominated mainstream visual culture for much of the twentieth century.

Arthur P. Bedou's archive is a rebuke to the flattened images of Black life that dominated mainstream visual culture for much of the twentieth century.

By KOLUMN Magazine

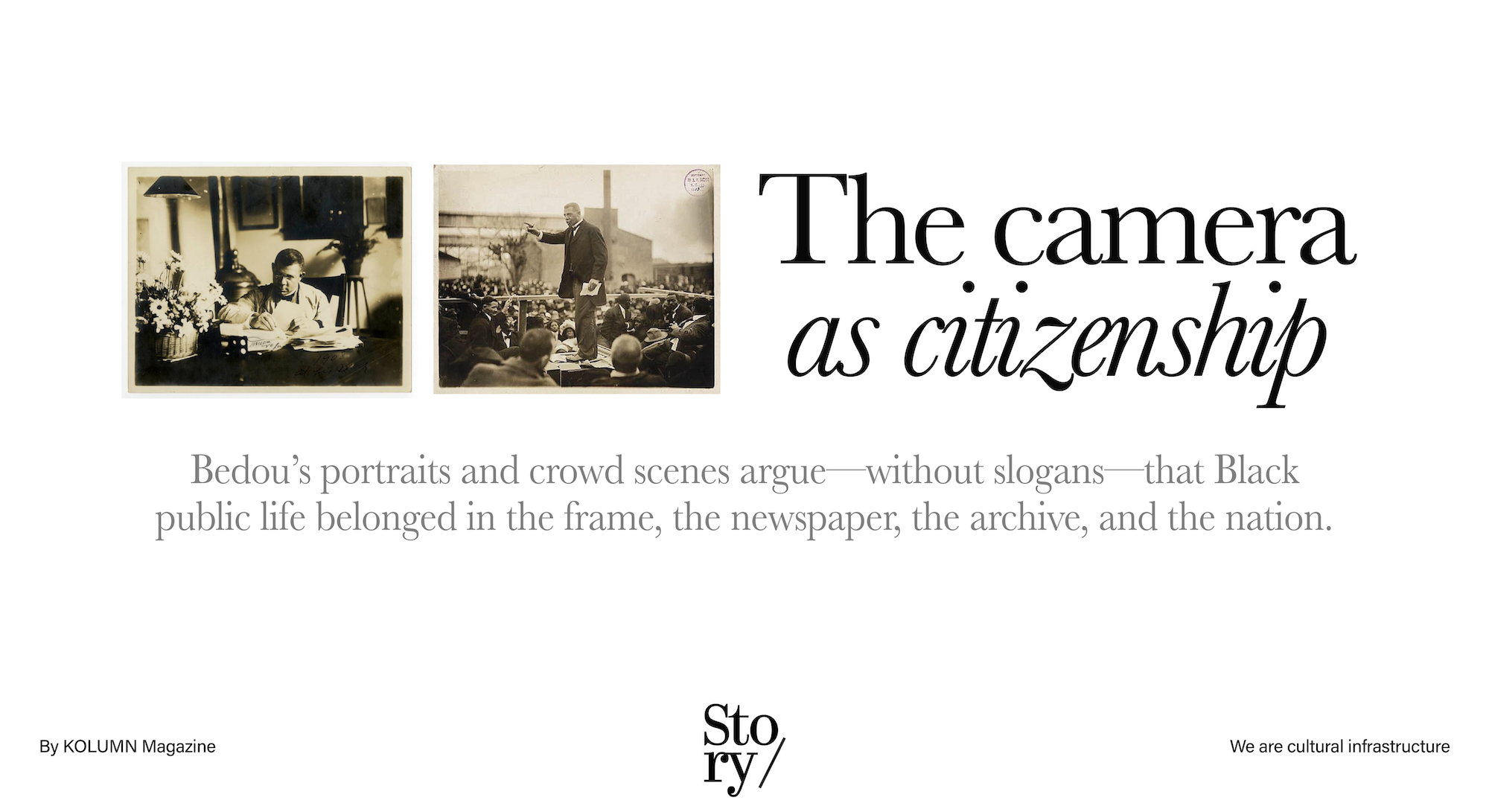

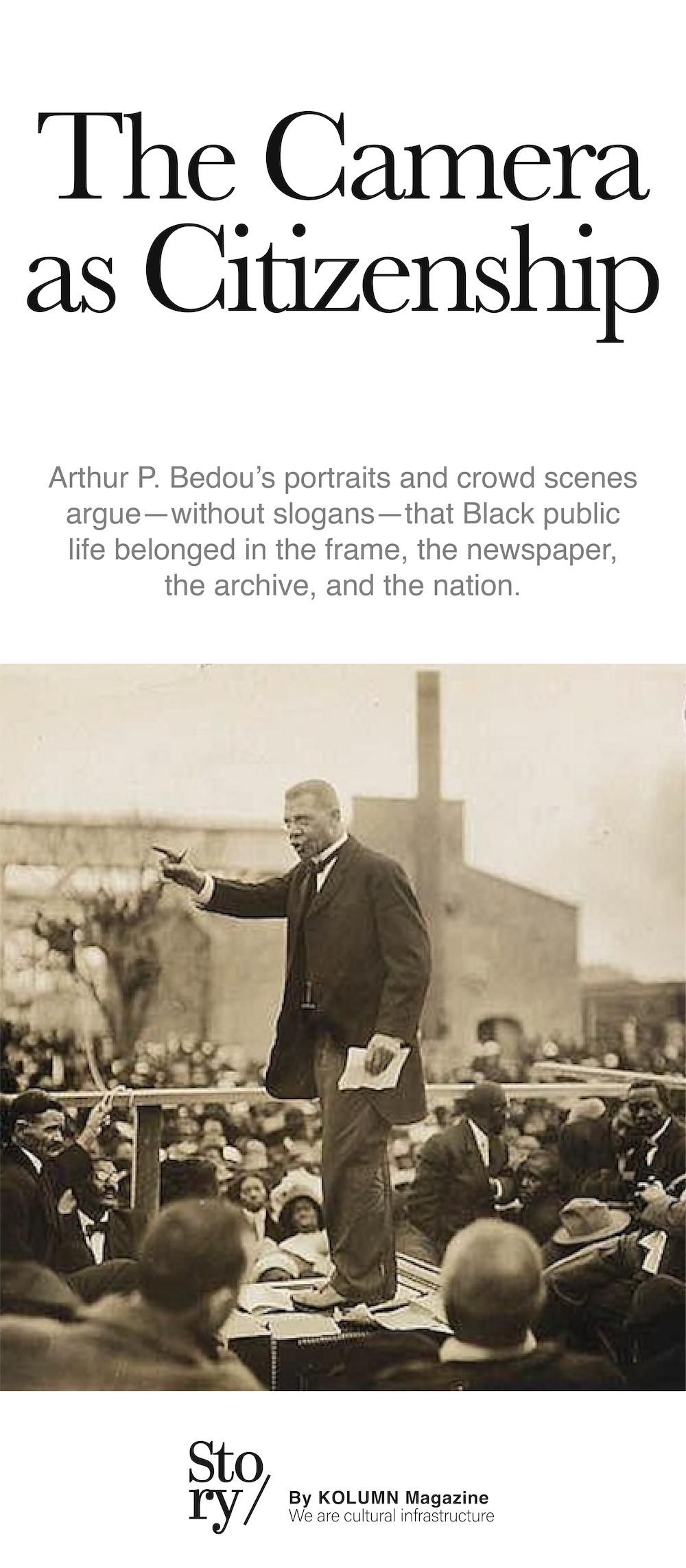

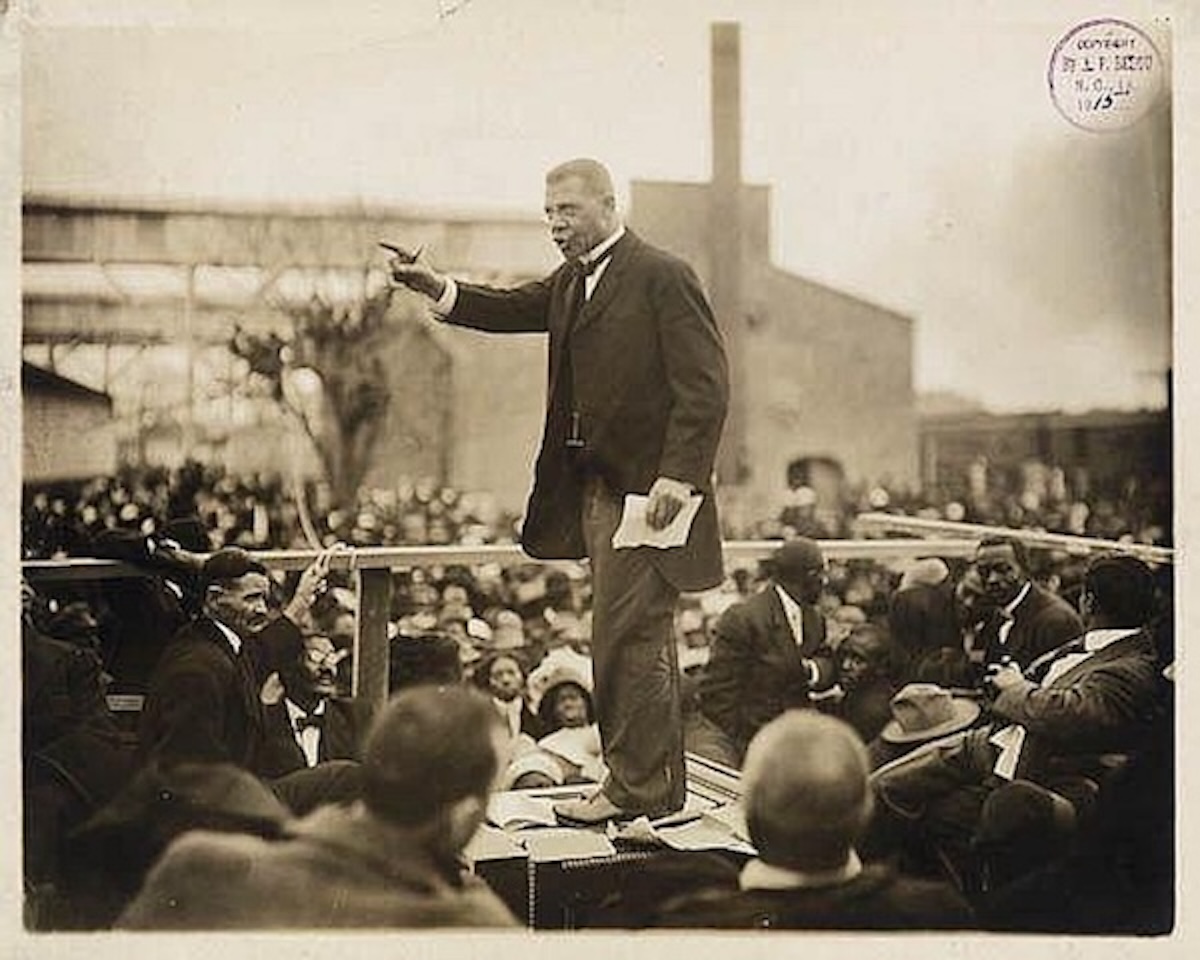

One photograph, made in Louisiana in the 1910s, refuses to behave like “history” in the safe, sealed-off way we are taught to expect. It is a crowd picture—hats and faces, posture and attention—organized around a stage and a speaker. The people are dressed for the occasion, not as costume but as declaration. The scene says: we have gathered, we have made time, we have built an audience and a public. And the act of photographing it says something just as pointed: this public deserves documentation.

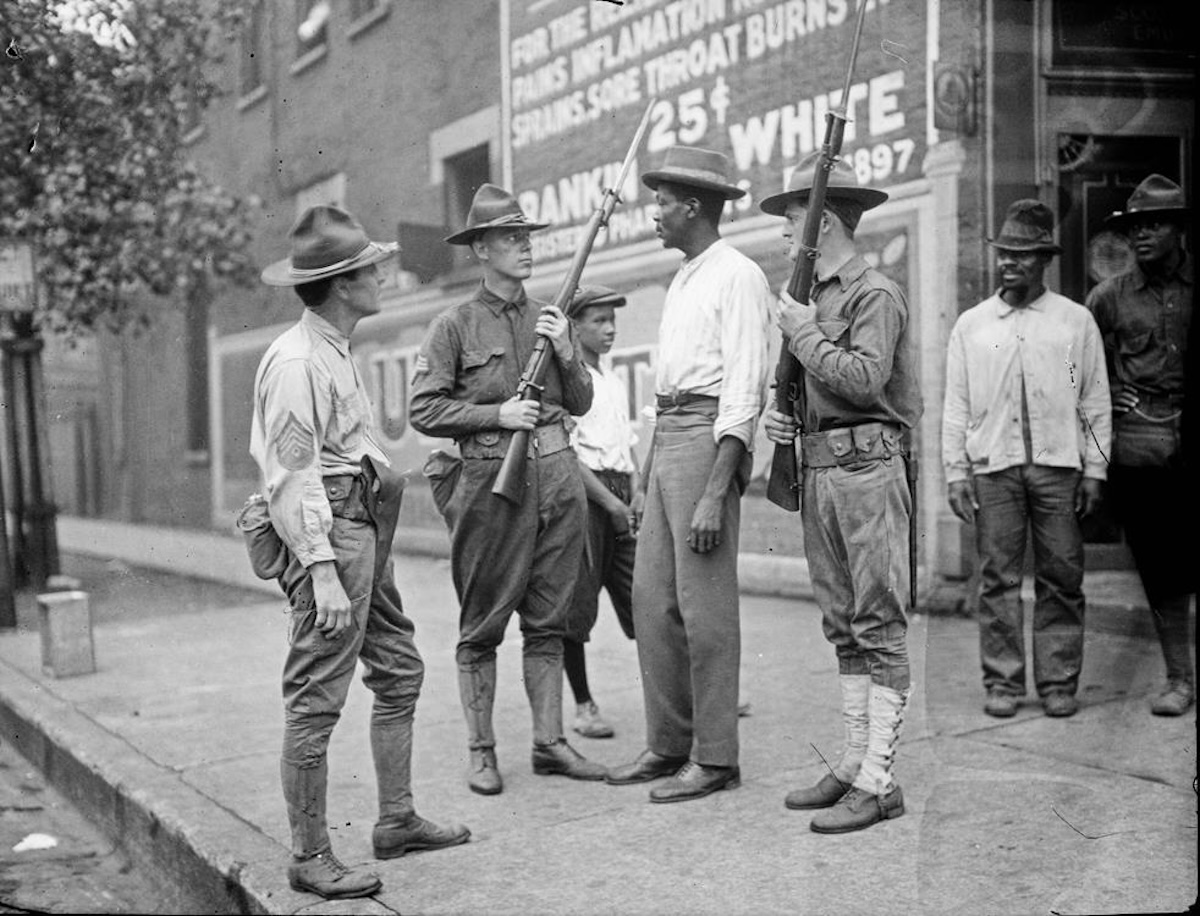

The Library of Congress catalog records the image as a view of Booker T. Washington speaking near New Orleans, credited to A. P. Bedou. The factual scaffolding—date, place, name—only hints at the deeper drama: the camera as witness to Black civic life at a moment when visibility could be dangerous, and representation could be weaponized. What Bedou captured was not just a famous man on a platform, but a geometry of aspiration: a community insisting on its own legibility.

Arthur P. Bedou did that kind of work for decades. He is often introduced, correctly, as Booker T. Washington’s personal photographer during the last years of Washington’s life, and as a leading Black photographer in New Orleans in the first half of the twentieth century. But those phrases, tidy as an encyclopedia entry, can shrink what is most radical about his career: Bedou was not merely near history; he helped history look like itself.

In the early twentieth century, images circulated with unusual force. Photography, already anchored in studio portraiture and newspaper reproduction, was becoming modern propaganda, modern advertising, modern proof. Washington—educator, fundraiser, political operator—understood this with almost unnerving clarity, and the historical record suggests that he valued the camera as a tool of public persuasion. Bedou, largely self-taught, learned to produce the kind of pictures that could travel: dignified portraits, bustling scenes, institutional pageantry, and the charged visual theater of public speech.

His photographs now live in a spread of repositories—university archives, museum collections, and digitized databases—where they do a second life of work: teaching later generations how to see what was there. Xavier University of Louisiana maintains a substantial Bedou collection and describes it as documenting a wide cross-section of Black life and institutional history in New Orleans. Museums such as the Museum of Modern Art hold at least one Bedou print—Booker T. Washington on Horseback (1915)—a small fact with big implications: the work has moved from local history to the canonized spaces where photography is treated as art as well as evidence.

What emerges from the archive is a figure who sits at the junction of multiple American stories: the politics of respectability and uplift; the development of Black institutions; the growth of New Orleans as a modern city; the rise of Black newspapers and social organizations; the contested spectacle of race in public space; and the economics of photography as a profession. Bedou’s life is not only a biography of a man with a camera. It is a case study in how a community authored itself visually, under pressure, and how that authorship lasted.

Growing up Creole, learning the trade, inventing an eye

Arthur P. Bedou was born in New Orleans in 1882 and died in 1966. Those dates place him in a generational corridor that witnessed Reconstruction’s afterlife, the hardening of Jim Crow, World War I and II, the Great Migration, and the long preface to the civil rights movement. New Orleans itself—port city, Catholic stronghold, Creole crossroads—offered Bedou a complex cultural grammar from the start.

Several biographical accounts describe him as having limited formal education and becoming, as a photographer, “largely self-taught.” The phrase can sound romantic, the familiar myth of talent rising despite deprivation. Yet in Bedou’s case, self-teaching was not a garnish; it was the method. Photography demanded technical understanding—light, chemistry, exposure—and a practical temperament—equipment, clients, sales, studio management. To build a long career without the usual ladders of training and patronage required an unusual kind of stubbornness.

One early origin story that recurs in summaries of Bedou’s life is a photograph he made of a solar eclipse around 1900, said to have received attention and helped mark the beginning of his career. Whether that single image functioned as a true turning point or as a convenient emblem, it points to something essential about Bedou: he was attentive to the public moment. An eclipse is a communal event—people look up together. Photographing it is, already, a decision to participate in collective experience as a recorder.

By the early 1900s, Bedou was moving in and out of institutional spaces where Black leadership congregated. One account notes that he photographed a conference at Tuskegee Institute in 1903—an early professional gamble aimed at visibility. Tuskegee, under Booker T. Washington, was a machine of image-making in its own right, carefully producing narratives of industriousness and progress for donors and the broader public. In such an ecosystem, a photographer could be more than a technician. He could become part of the institution’s persuasive apparatus.

That is, essentially, what happened.

Booker T. Washington’s last decade, and the making of a visual strategy

Booker T. Washington did not merely sit for portraits; he traveled, spoke, posed with dignitaries, toured schools and factories, and cultivated an aura of national indispensability. Bedou, for a period, accompanied him and documented that world—especially from roughly 1908 to 1915, the year of Washington’s death, according to commonly cited biographical accounts. The resulting images—Washington speaking, Washington traveling, Washington among crowds—function as both biography and political instrument.

There is a revealing comment in a Washington Post feature about photography and public space: it notes an image of Washington taken in Louisiana by Bedou and quotes a scholar reflecting on the rarity—and danger—of Black men occupying public space in that era, as well as Washington’s understanding of “the power of image.” The point matters beyond Washington. It tells us why Bedou’s presence was consequential. A camera in the wrong hands could degrade; a camera in a trusted collaborator’s hands could build.

One of the simplest, and most enduring, facts about Bedou is that he photographed Washington in Louisiana in 1915, during Washington’s last tour of the state; the image has become a kind of shorthand for that period. In reproductions, we often focus on Washington himself. Bedou’s achievement is the larger frame: the crowd, the posture of listening, the choreography of attention. The photograph asserts that Black civic life was not hidden, not marginal, not illegible. It was organized.

MoMA’s collection entry for Booker T. Washington on Horseback (1915) adds another layer: it recognizes Bedou as an artist whose print belongs to a major museum’s photography holdings. That institutional validation, while belated, helps correct a common misunderstanding. Bedou was not only making documentary records for immediate consumption. He was making photographs that could survive—compositionally, materially, conceptually.

The Washington years also expanded Bedou’s access. Sources note that, through the Washington connection, Bedou photographed prominent figures across racial lines and spheres of influence, including George Washington Carver and Theodore Roosevelt, among others. These commissions are easy to read as career highlights—celebrity by proxy. But they also illustrate a deeper pattern: Bedou’s camera moved along the fault lines of American power. He photographed the people who shaped policy, philanthropy, education, and culture, and he photographed the institutions and communities that lived with the consequences.

The work was also entrepreneurial. One biographical account notes that Bedou turned some Washington images into postcards, Christmas cards, and calendars—formats designed for circulation and income. Here, the photographer is not simply recording history; he is packaging it, distributing it, and sustaining himself through the market for images. In a segregated economy, that mattered. Photography was one of the few professions in which Black practitioners could build independent businesses, though not without constraints and vulnerability.

New Orleans as subject: Family, ceremony, and the politics of being seen

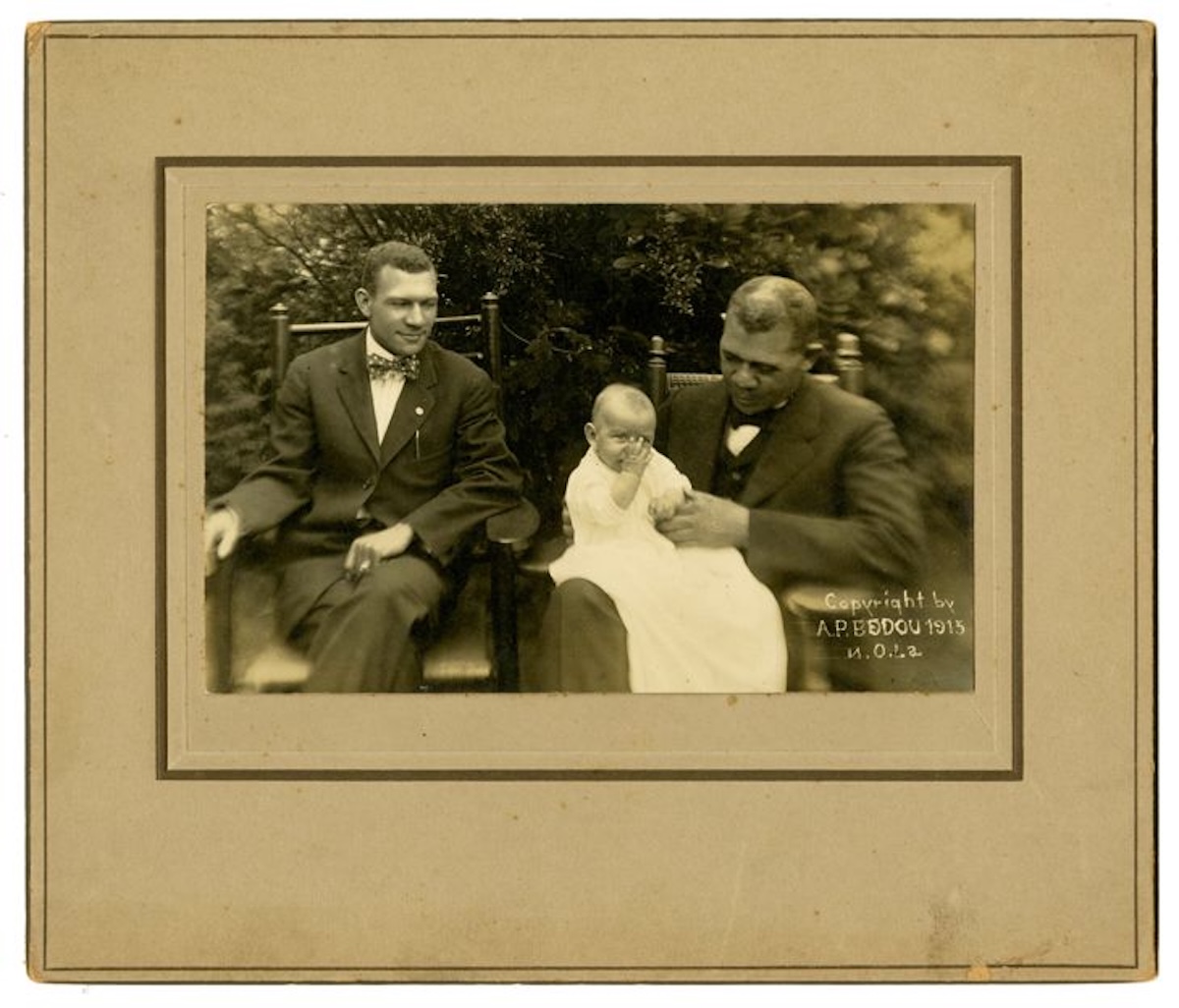

If the Washington photographs gave Bedou national reach, New Orleans gave him his long subject: Black life as lived, not merely as argued for. Accounts of his later career describe him opening a studio in New Orleans in the 1920s and photographing families, children, community events, and visiting performers and speakers. The everyday work of a studio photographer can appear, from a distance, like routine commerce: sitters arrive, pose, pay, leave. But in Black communities, particularly in the early twentieth century, studio portraiture carried a specific voltage. It was a controlled environment in which clients could present themselves on their own terms—clothing, posture, expression. It was self-fashioning, archived.

Bedou’s images, as they survive in university collections and exhibitions, reveal an aesthetic of dignity that does not need to announce itself. The sitters often meet the camera with a steadiness that reads as both personal confidence and a learned performance: the knowledge that an image may outlast you, may represent you to strangers, may travel into contexts you cannot control. That awareness shaped how Black people posed and how Black photographers framed them.

New Orleans added still more complexity. The city’s Creole culture, its Catholic institutions, its layered racial categories, and its public rituals created opportunities for a photographer attuned to ceremony. One discussion of Bedou’s place in local history describes him as born in Tremé and as a descendant of French-speaking Creoles, noting his national reputation and his work documenting African American community life. A different scholarly framing highlights the broader ecosystem of Black studio photography and argues, implicitly, that such photographers created a parallel visual record to the one dominant white institutions produced.

Bedou photographed not just people but institutions—schools, churches, professional organizations. Sources tie him to the National Negro Business League and other major Black professional bodies, describing him as an “official photographer” for such organizations. That role matters because it suggests repeat access and trust. Photographing organizations is not like photographing a parade where anyone can stand at the curb. Institutional photography requires permission, proximity, and an understanding of what the institution wants to project. Bedou became, in effect, a visual civil servant in Black public life.

Xavier University and the long view of Black Catholic education

One of the richest veins of Bedou’s surviving work is tied to Xavier University of Louisiana, the historically Black Catholic institution in New Orleans. Xavier’s archives hold extensive Bedou photographs spanning decades, and the university itself has highlighted Bedou’s role as a self-taught photographer whose work documented campus life and broader community history.

To photograph a campus over many years is to participate in a slow narrative: students arrive, graduate, become alumni; buildings rise; sports teams pose; formal events and religious ceremonies unfold. These images create continuity, especially for institutions that faced chronic underfunding and the structural hostility of segregation. They are proof of endurance.

Bedou’s relationship to Catholic New Orleans appears not only in his work but in biographical notes describing him as a devout Catholic affiliated with a local parish. This detail is more than personal piety. Catholic networks—schools, orders, churches—were major pillars of community life. Bedou’s photographs of religious communities and Catholic institutions become, therefore, an archive of a distinctive Black Catholic experience that is often underrepresented in mainstream narratives.

In recent years, historians and curators have increasingly foregrounded Black studio photography as an essential part of American visual culture, and Bedou has benefited from that shift. Articles and exhibitions about nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Black photography in New Orleans have used Bedou’s work to illustrate themes of self-representation and institutional life. The effect is to move Bedou from “local documentarian” to “central witness” in the story of how Black communities constructed modern identity through images.

Jazz, celebrity, and the city’s modern pulse

New Orleans is inseparable from the mythology of jazz, and photographs often function as proof-texts for that mythology. Bedou’s work intersects with this cultural narrative in multiple ways. Accounts of his career mention photographing jazz bands and speakers visiting the city, with images appearing in newspapers such as the Louisiana Weekly and the Times-Picayune.

Even when individual prints circulate through auctions or private collections, the descriptions often point to Bedou’s role as a chronicler of Black cultural life—capturing musicians and public gatherings. Auction listings are not, by themselves, reliable biographies, but they do reflect how Bedou’s name has become attached to certain genres of imagery: the studio portrait, the band photo, the formal event. More trustworthy are academic and archival references tying Bedou to jazz-related holdings, including documentation that a photograph credited to Bedou appears in scholarly material connected to Tulane’s Hogan Jazz Archive.

The point is not to claim Bedou as a “jazz photographer” in the narrow sense. Rather, it is to note that his camera was present in the same social world jazz inhabited: Black New Orleans as a network of venues, churches, schools, clubs, newspapers, and professional associations. In that world, musicians were not merely entertainers; they were public figures, part of the city’s self-image.

Bedou’s photographs, then, become part of the infrastructure of cultural memory. They provide faces for names, style for eras, proof for stories that might otherwise drift into legend. In that sense, he belongs in the lineage of photographers whose work makes cultural history feel tactile.

Bedou as businessman: Photography, property, and institutional investment

A common trap in writing about early Black photographers is to treat them as isolated artists—heroic individuals working against racism, full stop. Bedou’s life suggests something more layered: he was also a businessman who built stability in a precarious economy.

Biographical accounts note that Bedou prospered, invested in real estate, and held leadership roles in business institutions, including involvement with the People’s Industrial Life Insurance Company of Louisiana. The specifics of those investments matter less than the broader fact: Bedou leveraged his craft into economic power, and he understood that the work of making images could underwrite the work of building wealth.

This is part of his significance. In the early twentieth century, Black wealth-building often relied on networks of churches, fraternal organizations, insurance companies, and small businesses—institutions that both served and depended on the Black community. A photographer who documented these networks and also participated in them occupied a dual role: recorder and stakeholder.

Photography itself was an enterprise of equipment and overhead. Studios required space, lighting setups, darkrooms, and staff or assistants. The clients—families, students, organizations—were not only subjects but a market. Bedou’s ability to operate for decades suggests that he achieved a rare balance between art, service, and commerce.

The archive as afterlife: Where Bedou’s work lives now

The afterlife of Bedou’s photographs is, in some ways, as important as the images themselves. Xavier University hosts a digitized Arthur P. Bedou Photographs Collection and presents Bedou as a leading Black photographer of New Orleans in the first half of the twentieth century. JSTOR, through its institutional partnerships, has highlighted the collection as part of broader efforts to surface Black history and visual archives.

The movement of Bedou’s work into widely accessible platforms changes what can be done with it. Scholars can trace patterns: recurring institutions, social rituals, the evolution of fashion, the geography of Black New Orleans, the visual language of respectability and modernity. Community members can locate ancestors, or at least locate the textures of a world that produced their families. Students can see that history is not only speeches and laws but faces and rooms and streets.

At MoMA, the presence of a Bedou print on the museum’s website signals another kind of afterlife: the transformation of documentary work into fine-art heritage. This shift is not neutral. When museums collect and exhibit photographs like Bedou’s, they influence which histories are considered aesthetically important, not just socially meaningful. The risk is that the images become detached from the communities that produced them. The opportunity is that they enter a broader conversation about photography’s role in modern life.

Bedou’s work has also appeared in discussions of Black studio photography as a genre and as a political practice. Essays and articles emphasizing “records of light” and the importance of Black photographers in documenting community life place Bedou among those who worked both inside and outside studio walls, capturing everything from formal portraits to crowded public events. Such scholarship reframes Bedou not as a footnote to Washington, but as a key maker of visual history in his own right.

Seeing uplift, seeing complexity

Any honest assessment of Bedou’s significance has to grapple with the ideological environment in which he worked. Booker T. Washington’s politics of uplift—emphasis on industrial education, economic self-reliance, and strategic accommodation—shaped how Washington wanted to be seen, and thus shaped the images Bedou made of him. Bedou’s photographs of institutions, professional organizations, and well-dressed crowds can be read as extensions of that uplift aesthetic: proof of discipline, proof of progress.

But Bedou’s broader archive complicates a purely “uplift” reading. Studio portraiture can encode aspiration, yes, but it also encodes individuality. Crowd images can show respectability, but they can also show the sheer density of communal life: children, elders, workers, students, clergy. Institutional photos can be propaganda, but they can also be evidence of internal complexity—gender roles, hierarchies, rituals, humor, fatigue.

The most powerful thing Bedou’s photographs do is insist on multiplicity. Black New Orleans is not a single story in his work. It is families and schools; it is church ceremonies and sports teams; it is visiting celebrities and local leaders; it is the practiced elegance of a studio portrait and the spontaneous energy of an outdoor event. The archive becomes a rebuke to the flattened images of Black life that dominated mainstream visual culture for much of the twentieth century.

That is why Bedou matters now. The current cultural moment is saturated with images, and yet the question of who controls representation remains live. Bedou’s career reminds us that representation has always been a field of struggle, and that one response to misrepresentation is not only critique but production: making the images you want the world to have.

A photographer’s legacy in a city that remembers

New Orleans is a city famously obsessed with memory—parades that reenact history, cemeteries built like neighborhoods, music that turns grief into choreography. Bedou’s archive fits that civic temperament. His photographs are a form of remembrance that is neither nostalgic nor sentimental. They are, at their best, precise.

When Bedou died in 1966, biographical accounts state that he left much of his fortune to educational institutions, and that a scholarship associated with his name exists at Xavier University of Louisiana. This final gesture—turning accumulated wealth back toward education—echoes the institutional worlds he spent his life photographing. It suggests that, for Bedou, the camera was not merely a tool for making a living. It was part of an ecosystem: image-making, institution-building, community investment.

If Booker T. Washington understood the “power of image,” then Bedou understood something adjacent: the power of continuity. A photograph is a preserved moment, but an archive is a preserved pattern. Bedou did not just take pictures. He built, inadvertently and then deliberately, a visual continuity for a people and a place.

In that sense, the crowd gathered to hear Washington in Louisiana is not just an audience in the past. It is an early version of us: people trying to see what is possible, and needing evidence that we were here, that we gathered, that we listened, that we spoke back to history with our own faces in the frame.

More great stories

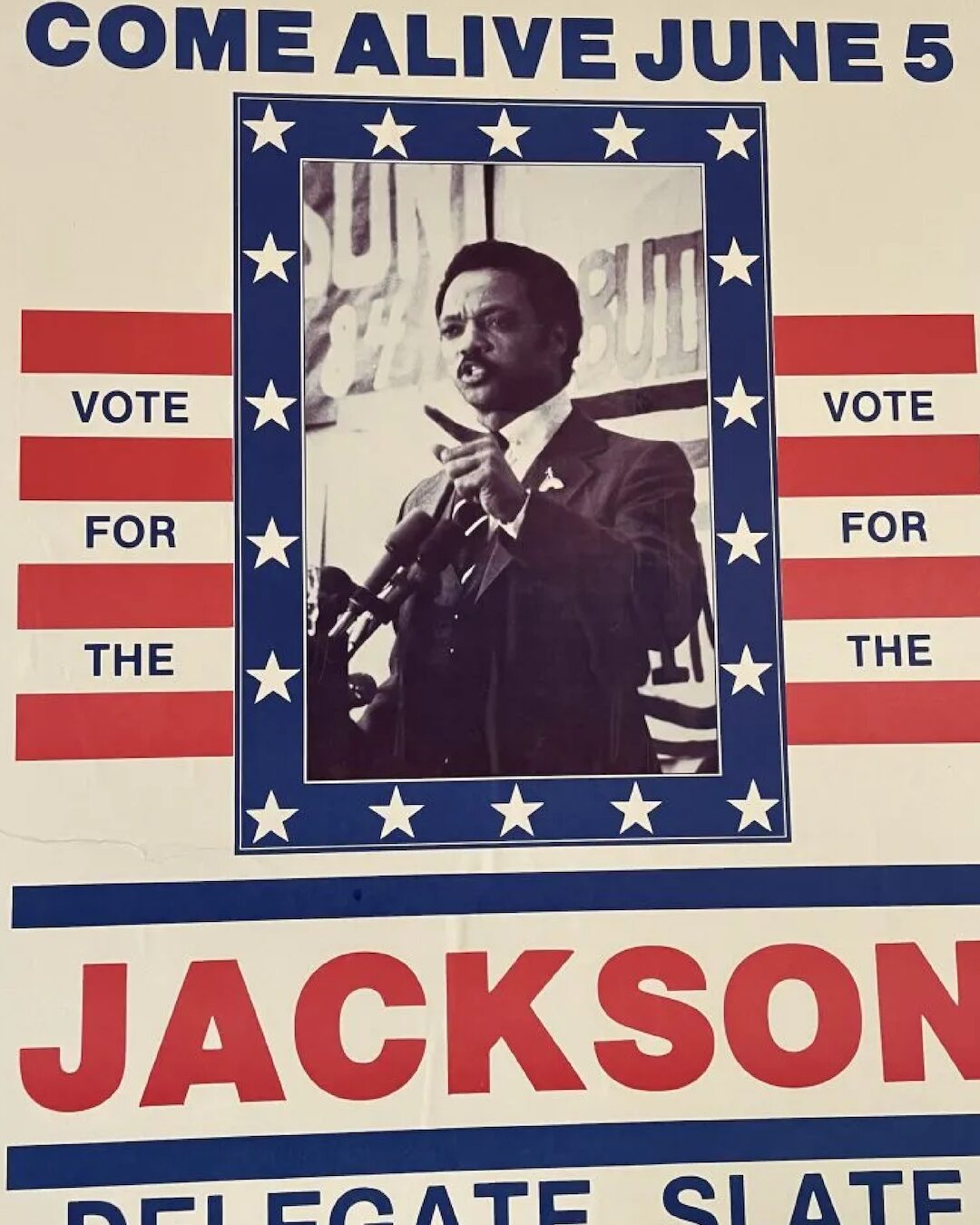

What a Campaign Can Be