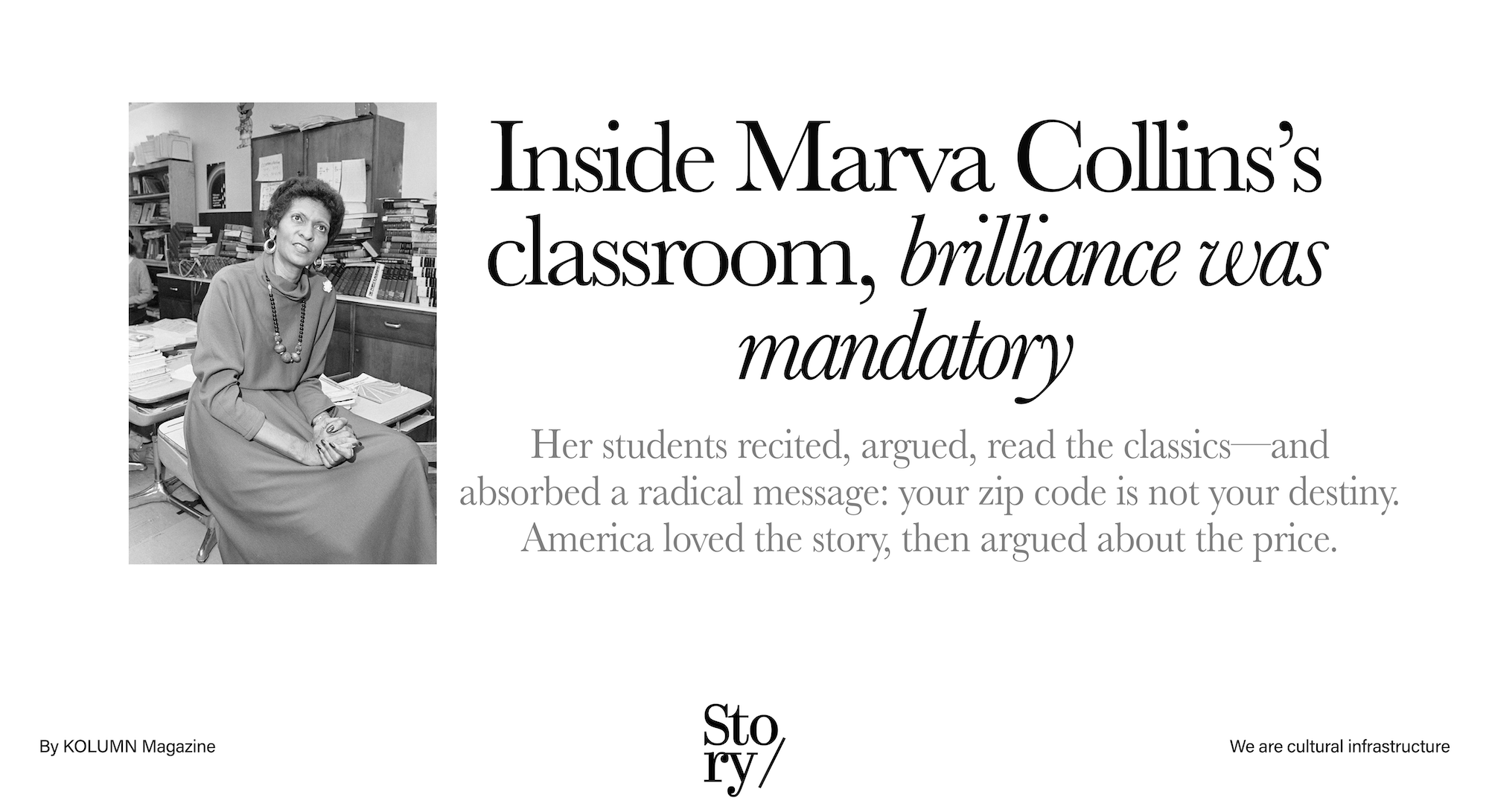

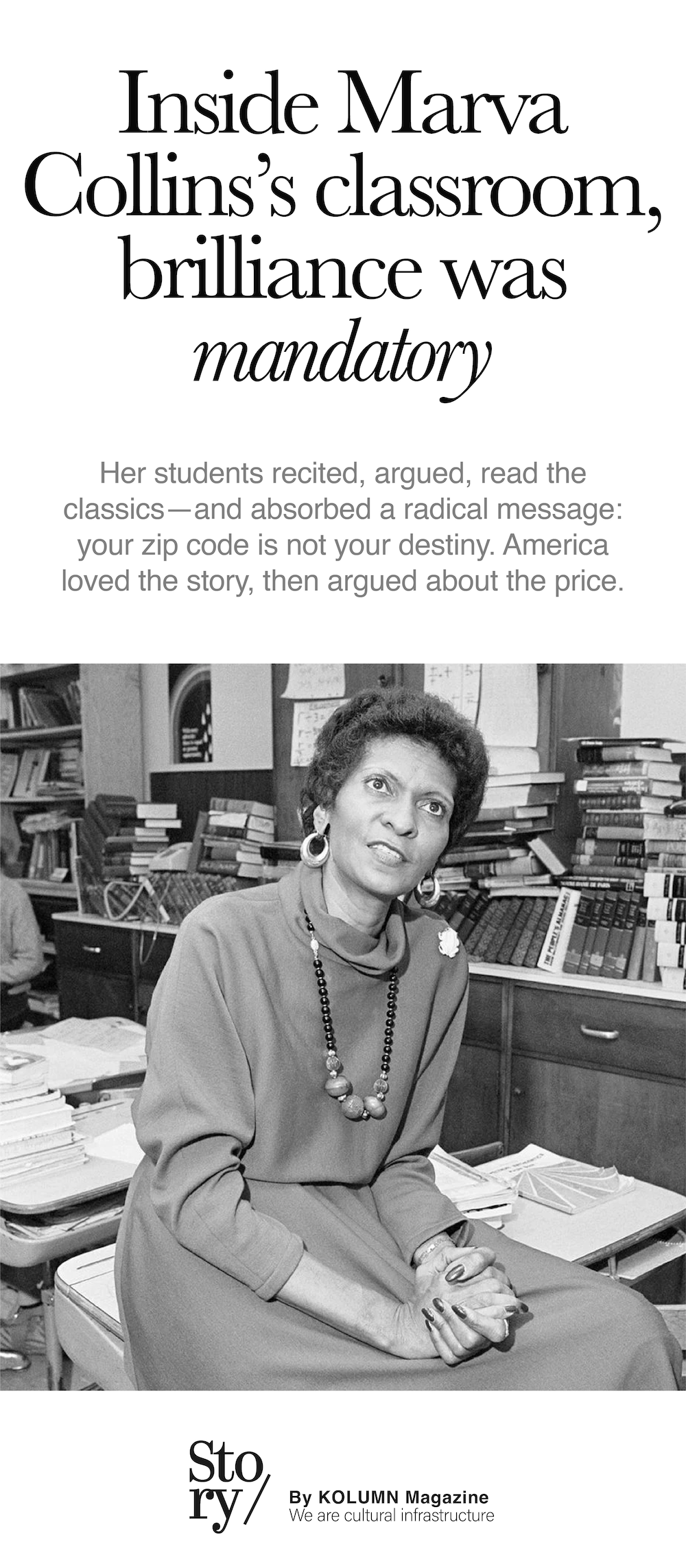

Marva Collins made demanding look like love. She made excellence sound like a birthright rather than a prize.

Marva Collins made demanding look like love. She made excellence sound like a birthright rather than a prize.

By KOLUMN Magazine

In the American imagination, teaching is one of the last professions still permitted a folk-hero narrative. A single adult enters a failing institution, refuses to accept its premises, and through force of personality and stubborn belief transforms children whom everyone else has decided are unreachable. The nation—always hungry for redemption that doesn’t require structural repair—embraces the narrative, stages it for television, and repeats it as reassurance: if one person can do it, then the system is not the problem. Or, in a darker reading, if one person can do it, then everyone else is simply not trying hard enough.

Marva Collins lived inside that contradiction for much of her public life. She was real—a woman with a biography, a marriage, children, bills, pride, exhaustion—and she was also an argument, drafted into America’s endless debate about public education, poverty, race, discipline, family, money, and expectations. She did not ask to be a symbol, exactly, but she did not flee symbolism either. She understood attention as leverage. She knew how to command a room. She could turn a phrase into a verdict. And she had a rare appetite for confrontation, especially when the prevailing orthodoxy insisted that children in poor Black neighborhoods could not or would not learn at high levels.

Collins’s name became synonymous with Westside Preparatory School, the low-cost private school she founded in 1975 in Chicago’s West Side, initially in her home, with money drawn from her retirement—often described as $5,000, a figure that functions in her legend the way a single match functions in a prairie fire story. Her premise was not complicated: “All children can learn,” she insisted—an assertion both banal and revolutionary depending on how fully a society has learned to doubt certain children.

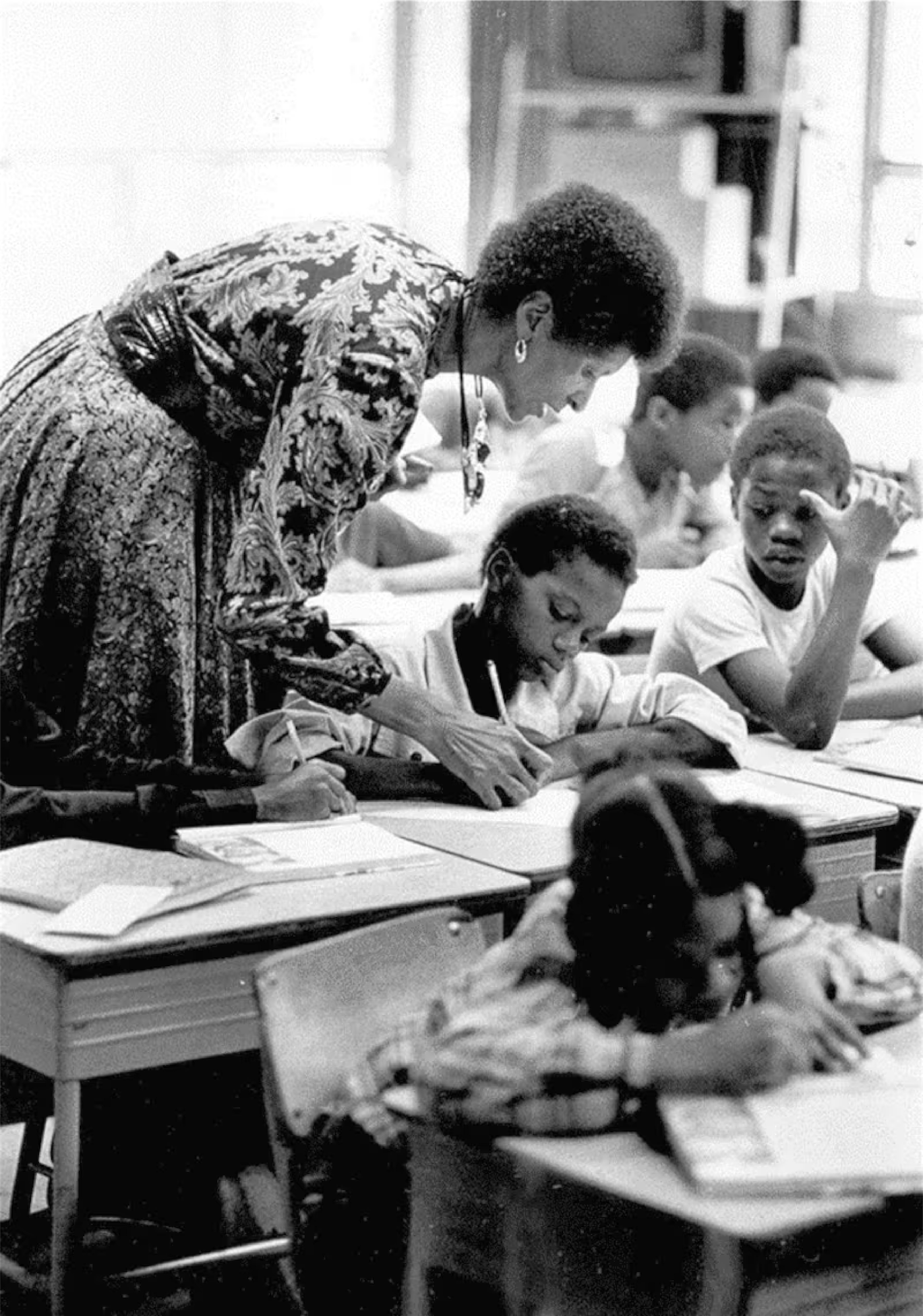

For years, the country watched her classroom as if it were a laboratory: students reading and reciting, debating and writing; a teacher using a Socratic style, correcting grammar, demanding complete sentences, refusing the soft bigotry of low expectations. The applause arrived quickly—national television, magazine profiles, speaking invitations, a made-for-TV film that placed her story into the Hallmark Hall of Fame canon, with Cicely Tyson embodying her intensity and Morgan Freeman playing her husband.

So did scrutiny. Some of it was predictable: when a Black woman claims expertise in a field that has traditionally policed authority—particularly when she challenges public institutions—skepticism is rarely far behind. Some of it was more specific: questions about claims, testing, finances, temperament, and the sustainability of a model that relied so heavily on one person’s force. The press that helped build her legend also tested its seams.

To write about Marva Collins with integrity is to refuse both easy outcomes. She was neither merely a miracle worker nor merely a media construction. She was an educator with a coherent philosophy, a disciplined practice, and a genuine impact on students and teachers—one recognized at the highest levels, including the National Humanities Medal awarded in 2004. She was also a figure whose fame made her a tool in arguments that exceeded her own intentions. Her life, in that sense, is not only the story of one school. It is the story of what America demands from its teachers, what it celebrates in them, and what it punishes when celebration curdles into suspicion.

Alabama beginnings, and the one-room schoolhouse in her memory

Marva Delores Knight was born in Alabama in 1936, in a segregated South that trained Black children early in the vocabulary of limits—where they could go, what they could touch, what they could expect. She grew up with the textures of rural life and the strictures of small-town schooling, and she carried, by many accounts, a formative memory of a one-room schoolhouse environment—orderly, demanding, intimate, and uncompromising. The details of those early classrooms matter because Collins later spoke and acted as someone trying to resurrect something she believed modern institutions had abandoned: not nostalgia, exactly, but clarity. A teacher, a set of texts, a moral expectation that children rise to meet the work.

She attended Clark College, now Clark Atlanta University, an HBCU with its own history of producing Black professionals who would be tasked with navigating institutions not built for them. After college she taught in Alabama before moving to Chicago, a migration that echoed the broader mid-century movement of Southern Black families seeking industrial opportunity and relative autonomy in Northern cities—only to meet new forms of segregation in housing, schooling, and employment.

In Chicago, Collins entered the public school system, working for years as a teacher—often described as a substitute teacher for a long stretch—inside a bureaucracy that, by the late 1960s and early 1970s, was contending with overcrowding, political patronage, labor tensions, and the compounded effects of residential segregation. She did not emerge from that system as a quiet reformer. She emerged as a critic.

Her critique, importantly, was not limited to resources. She did not simply argue that poor schools needed more money, though she understood material deprivation. She argued that the system’s intellectual and moral posture toward certain children was broken—that adults had been trained to interpret poverty as destiny and to treat remedial tracks as realism rather than surrender. That critique placed her in conflict not only with administrators but with a broader educational culture that, in those decades, was increasingly shaped by debates over progressive pedagogy, open classrooms, tracking, special education labels, and the politics of testing.

In Collins’s telling, the system had misnamed children. It had labeled them “learning disabled” or “unteachable” when, in her view, what they lacked was not capacity but instruction, discipline, and exposure to a serious curriculum. Her gift—one that admirers experienced as liberation and critics sometimes experienced as arrogance—was her willingness to say so plainly.

The $5,000 decision, and the birth of Westside Preparatory School

In 1975, Collins made the move that would define her: she used money from her retirement—repeatedly cited as $5,000—to open Westside Preparatory School in Chicago’s West Side, initially operating out of her home. The origin story is often recounted with a kind of cinematic inevitability: fed up with the system, she decides that the only way to prove her point is to build the alternative herself.

Yet the decision was neither purely symbolic nor purely individual. It was a form of economic risk that many teachers could not take. It was also a form of social risk. A Black woman starting a private school in a poor neighborhood—charging tuition, asserting authority outside the public system—invited suspicion from multiple directions. There was the question of legitimacy: who is allowed to found a school, and under what oversight? There was the question of politics: was she undermining public education or exposing its failures? There was the question of class: could low-income families afford tuition, and what did it mean to ask them to pay for what public schools were supposed to provide?

Collins’s answer was pragmatic and moral at once. She wanted autonomy over curriculum and expectations. She wanted to free herself from what she saw as the system’s excuses—excuses she believed were often dressed up as compassion. She built a model that was described as low-cost and that welcomed children whom others had written off.

And she taught them with a style that was both old-fashioned and idiosyncratic. She used constant questioning—Socratic prompts that required students to explain their reasoning, not merely offer a correct response. She demanded recitation and repetition, treated grammar as a form of respect, and insisted that children learn to speak with precision. She built classroom culture around attention: eyes forward, bodies still when needed, voices clear. The environment, in many accounts, was lively but disciplined—more like a seminar than a holding pen.

One of the most controversial and compelling aspects of her pedagogy was her use of “the classics”—a canon that some educators associated with elite institutions rather than inner-city classrooms. Collins treated that association as precisely the point. Why, she asked, should Shakespeare or Socrates or the broader inheritance of Western literature be hoarded? If the canon was a form of cultural power, then excluding Black children from it was not neutral—it was theft. A recent Washington Post opinion essay, reflecting on Collins’s example, recalled her insistence on the classics as a way of opening children to “the universal human story.”

She also insisted on something that sounds simple until you try to enforce it in a classroom shaped by trauma and instability: responsibility. “I don’t make excuses—I take responsibility,” the National Humanities Medal citation quotes her saying; “If children fail, it’s about me, not them.” That line is part of her legend because it flatters a certain American sensibility: individual accountability, bootstrap moral clarity. But in Collins’s classroom it also functioned as a refusal to let adults off the hook.

Fame arrives, and the classroom becomes a stage

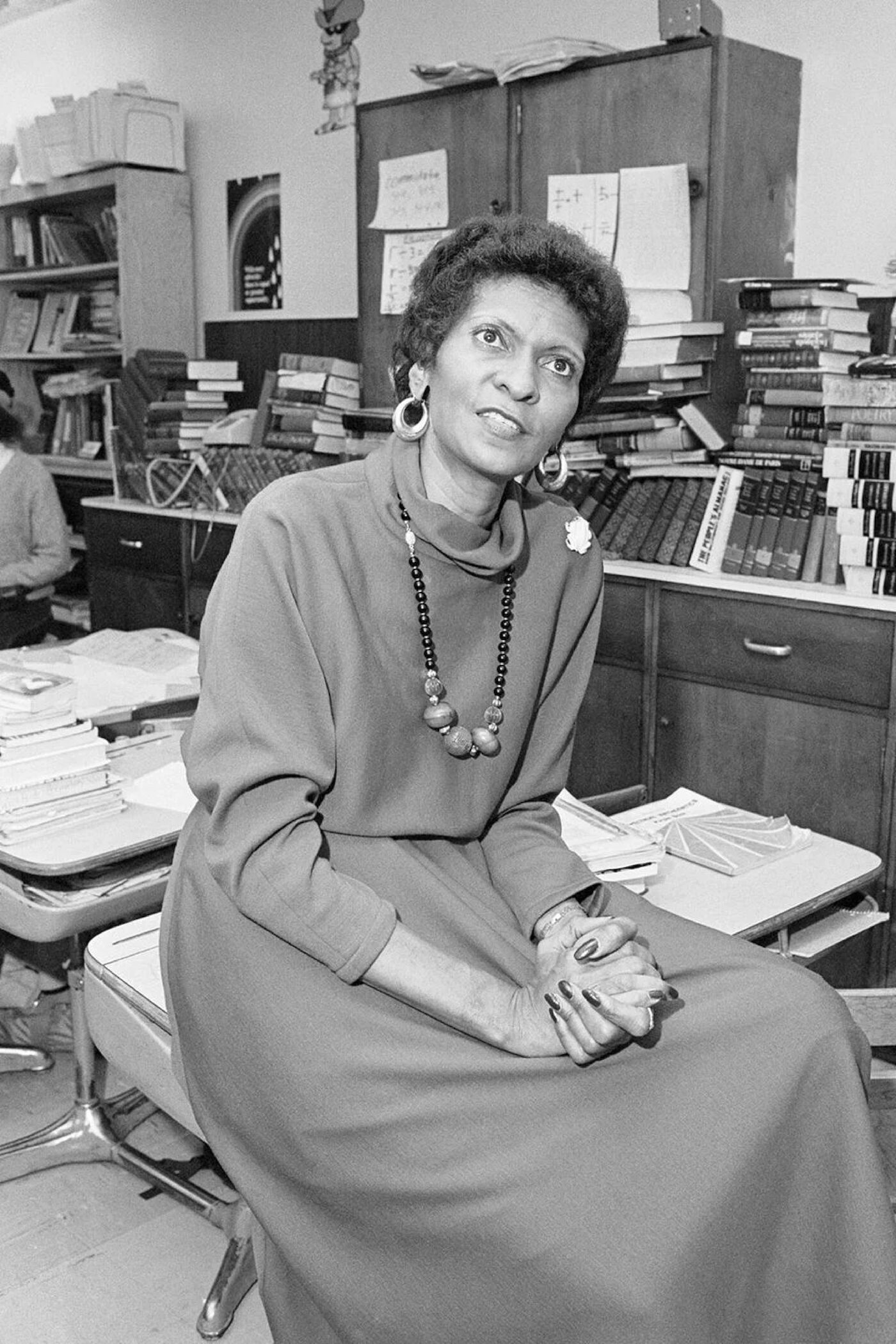

By the late 1970s and early 1980s, Collins and Westside Prep became a national story—first through local press attention, then broader coverage and television features. A “60 Minutes” profile helped cement her reputation in the popular imagination, presenting her as an antidote to failing schools and a rebuke to lowered standards. Donations and curiosity followed. The school grew. The idea of “the Marva Collins method” began to circulate as if it were a replicable formula.

Then, in 1981, her story was dramatized in The Marva Collins Story, a Hallmark Hall of Fame television film. Cicely Tyson played Collins with a controlled ferocity that mirrored Collins’s public persona: the teacher as moral force, the classroom as battleground, the child as possibility rather than pathology. The film did what such films often do: it tightened narrative arcs, elevated conflict into plot, and offered catharsis that real classrooms rarely provide on schedule. But it also immortalized a truth about Collins’s impact—she made teaching look like something consequential enough to dramatize.

Fame, however, is never neutral for educators. It changes the work. A teacher who becomes a national emblem must now manage not only children but cameras, donors, reporters, speaking engagements, and the projections of strangers. Fame also invites the suspicion that the work is performance rather than substance, that charisma is being mistaken for results.

The period produced both laudatory profiles and skeptical examinations. A 1980 Washington Post feature described her as a “wiz teacher,” noting the sense of miracle that surrounded her work while also emphasizing her insistence that she was simply doing what good teachers could do in the right atmosphere—a claim that simultaneously democratized and challenged the profession.

But by 1982, coverage also reflected turmoil: internal disputes, questions about finances and governance, critiques from teachers, and the strain of being a symbol. (The Washington Post) A Christian Science Monitor article that year captured some of the tension—allegations and counter-allegations, and the way her school’s success story had become vulnerable to the same institutional conflicts that plague larger systems.

A UPI piece from 1982 framed the conflict as an attempt to locate “truth, myth or somewhere between,” pointing to accusations that achievements were overstated and that independent validation was insufficient. Whether one reads such scrutiny as overdue accountability or as a predictable backlash, the fact remains: Collins’s work was now being judged not only by the families who chose her school but by a national audience eager to decide what her story meant for policy.

This is where Collins becomes especially interesting—not simply as a teacher but as a figure in the politics of education. She was embraced by some advocates of “school choice” as proof that alternatives to public systems could work for low-income children, and as an indictment of bureaucracy. At the same time, many public-school defenders viewed her as an exceptional case—an outlier whose success, even if genuine, could not be scaled, and whose fame was being used to justify abandoning public responsibility.

Collins did not fit neatly into ideological boxes. She criticized public schools harshly, but she also insisted that teachers—not markets—were the crucial variable. Her method was intensely relational and labor-intensive. It required attention, constant feedback, and a teacher willing to hold authority with confidence. In that sense, she was less a triumph of privatization than a rebuke to any system that expects children to learn without being taught well.

What her pedagogy actually was

If you strip away the legend, what did Collins do?

She built instruction around language. She treated reading not as an isolated “skill” but as a portal into thought and citizenship. She wanted children to speak clearly because she wanted them to think clearly—and because she believed that command of language is a form of power, especially for children whom society is prepared to misinterpret. Accounts of her classroom often note her emphasis on complete sentences, correct grammar, and verbal confidence.

She used questioning as a discipline. The Socratic method, in its best form, is not simply asking questions but training students to justify claims, to notice contradictions, to revise, to persist. Collins used that tradition in a context where many children had been trained to keep their heads down and minimize risk. In her room, silence could be a form of hiding; she demanded presence.

She insisted on content that many educators reserved for older or more privileged students. The Los Angeles Times, reflecting on her fame in the mid-1980s, described the sensation of a teacher who could motivate children to read Shakespeare and Dante—names that, in mainstream imagination, marked an almost absurd contrast with “inner-city” stereotypes. That contrast was part of her strategy. She wanted to shatter the mental picture of what poor Black children were capable of doing.

She framed excellence as both expectation and love. Collins’s style could be severe, but her severity was not nihilistic. She praised students, embraced them, called them brilliant, required them to “speak up,” and created a classroom identity in which intellectual seriousness was normal.

And she carried a moral narrative. In official recognitions of her work—particularly the National Humanities Medal materials—Collins emphasized responsibility, the refusal of excuses, and the notion that failure is costlier than the difficulty of excellence. To some educators, this language reads as inspirational. To others, it can sound like a minimization of structural obstacles. The truth, as with many moral narratives, is that it can function both ways. Collins used it to empower children and indict adults. Others used it to argue that poverty is irrelevant if the teacher is tough enough.

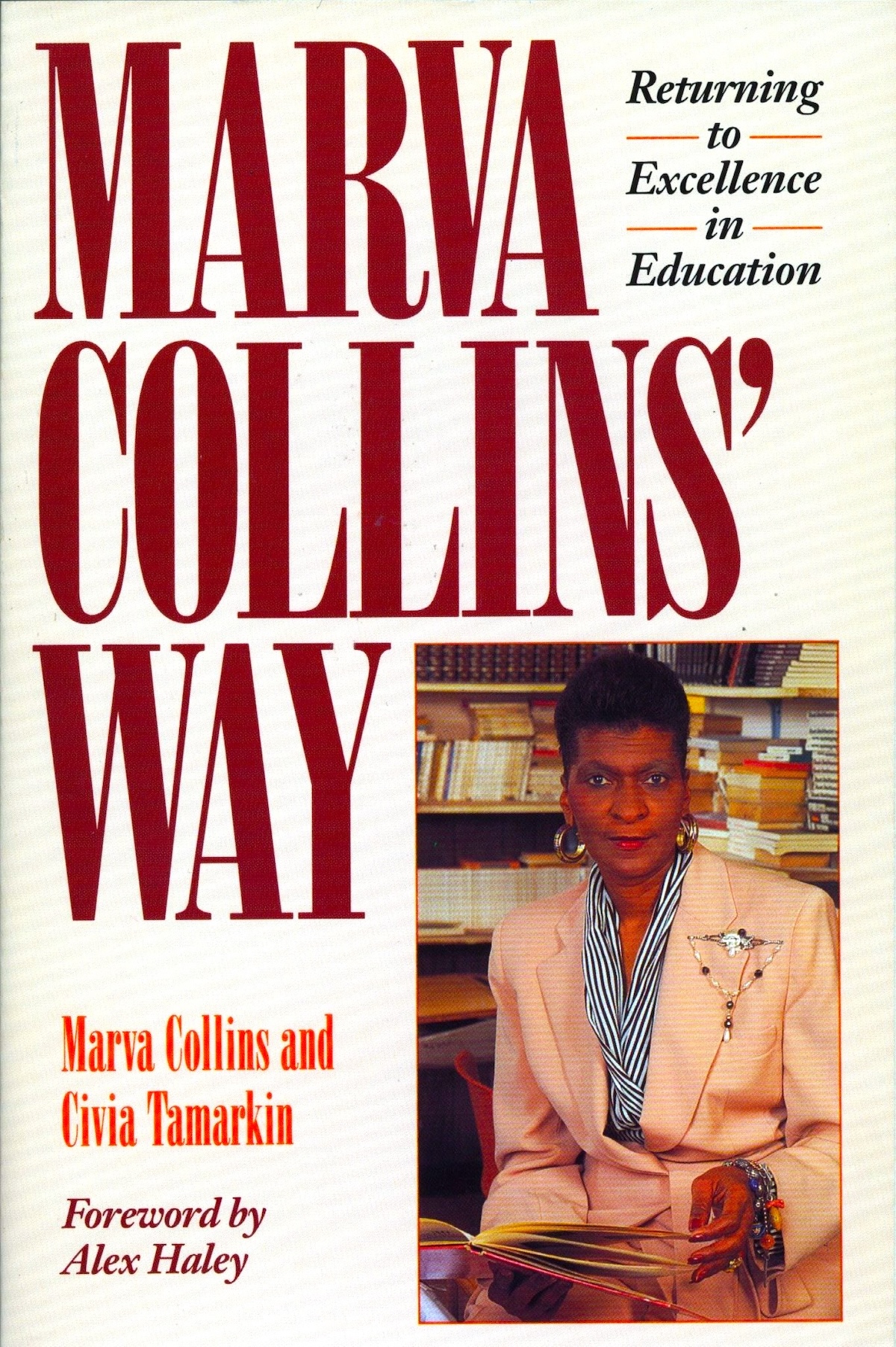

One measure of how influential she became is not simply how many students she taught but how widely her method was circulated. The National Humanities Medal page credits her with training large numbers of teachers, administrators, and principals in her methodology—suggesting that she understood her work as something to disseminate, not merely to perform in one school. She also wrote about her approach and marketed it through books and speaking, including Marva Collins’ Way and Ordinary Children, Extraordinary Teachers, extending her reach beyond Chicago.

The critic will note that dissemination is not the same as replication. A method taught in workshops can lose its essence if that essence depends on the founder’s presence. The admirer will counter that no pedagogy replicates perfectly; what matters is whether it raises the profession’s ambition. Collins’s life invites that debate rather than settling it.

The backlash question: Accountability, temperament, and the cost of being exceptional

The most responsible way to address controversy around Collins is not to sensationalize it but to locate it in the broader pattern that follows educators who become national symbols.

There were disputes and allegations in the early 1980s—about finances, about claims, about working conditions, about whether results were independently verified to the satisfaction of critics. Minnesota Public Radio, reflecting on her story after her death, noted that she was “stung” by accusations that she was not certified and that she had overstated her record—while also emphasizing that parents and supporters defended her and her impact.

These are not trivial issues. Schools—public or private—owe families transparency and accountability. Yet it is also true that Collins’s critics were not always arguing purely about accountability; they were also arguing about what her existence meant. If she was real, she was dangerous to certain narratives: dangerous to the narrative that poverty inevitably produces low achievement; dangerous to the narrative that public systems were doing all that could be done; dangerous to the narrative that Black children needed only care and resources but not rigor; dangerous, too, to simplistic narratives of market salvation, because her model was not a slick corporate charter brand but a teacher-centered enterprise driven by will.

Even the language used about her hints at the cultural charge. She was called a “miracle worker,” a phrase that flatters while also isolating. A miracle is, by definition, not repeatable. Once you frame a teacher as miraculous, you excuse everyone else from learning how she did it. But you also set her up for a fall, because miracles are held to impossible standards. The Washington Post’s 1982 account of her “fraying” success story captured this dynamic: the very fame that crowned her made her a target when institutional stress and human conflict emerged.

Collins’s temperament—her refusal to soften, her pride, her impatience with bureaucratic language—also shaped how conflict played out. She did not present herself as a consensus builder. She presented herself as a truth teller, and truth telling in education often collides with the fact that schools are not merely instructional spaces but political organizations with payrolls, hierarchies, and competing interests.

The deeper question is not whether Collins was perfect. No honest portrait would suggest that. The deeper question is what America expects when it asks one teacher to carry an entire debate on her shoulders. Collins’s story demonstrates the seduction of exceptionalism: we would rather celebrate the extraordinary teacher than build ordinary conditions under which many teachers can do extraordinary work.

Recognition and the long afterlife of her argument

In 2004, nearly three decades after she opened Westside Prep, Collins received the National Humanities Medal. The honor matters not simply as decoration but as evidence that her work was understood—at least by some national institutions—as culturally and civically significant. Education, in that framing, is not only about workforce preparation. It is about citizenship, language, history, and the inheritance of ideas. Collins’s insistence on the classics aligns with that humanities claim, and the medal citation frames her work as demonstrating “the potential of every child to learn.”

Her legacy also persisted through media revisitations. “60 Minutes” returned to her story years later, and other outlets reflected on former students and the endurance of her influence. That revisitation impulse is telling: America wanted to know whether the children in the legend grew into adults who could testify to its truth.

Her name continued to circulate in debates about curriculum, discipline, and Black educational leadership. Word In Black, in a 2023 list of Black women educators people should know, placed Collins within a lineage of women who combined critique with institution-building—an implicit argument that her story is not a lone anecdote but part of a broader tradition of Black women designing educational possibilities when systems fail.

Ebony, reporting on her death, framed her as a Chicago education activist and pioneer, pointing readers back to Westside Prep and the “Collins Method,” underscoring that her legacy was understood not only in policy circles but in Black public discourse about education and self-determination.

And mainstream reference works continue to summarize her as an educator who broke with a public system she believed was failing inner-city children, emphasizing her rigor and her insistence on cultivating independence and accomplishment.

These afterlives are important because they reveal how Collins’s meaning shifts with the era. In the 1970s and 1980s, she was a rebuke to an anxious nation confronting urban decline and school desegregation battles. In later decades, she became part of the “choice” conversation and the rise of alternative schools. In the 2020s, she is sometimes invoked in debates about “classical education,” canon, and culturally responsive pedagogy—debates that often talk past each other.

Collins’s life suggests a more complicated synthesis: a Black educator using canonical texts not to assimilate into whiteness but to claim intellectual inheritance; a disciplinarian whose discipline was tied to affection and belief; a critic of public systems whose work nevertheless depended on the dignity of teaching as a public good.

The question of scale, and why it haunts every conversation about her

Every famous teacher story ends at the same cliff: can it be scaled?

On the one hand, Collins plainly believed her methods could be taught to others. She trained educators, wrote books, spoke publicly, and framed her approach as a replicable philosophy rather than a personal gift. She argued, in essence, that the profession had chosen the wrong assumptions and could choose differently.

On the other hand, the very features that made her remarkable—her command, her rhetorical power, her relentless attention—are difficult to mass-produce. Systems are built around averages. Collins was not average.

This is not a sentimental point; it is an institutional one. Schools are organizations, and organizations often defend themselves against the kind of intensity Collins embodied. Intensity costs time. It costs emotional energy. It can burn out teachers and frighten administrators. Collins’s classroom—if we believe the descriptions—required sustained adult focus and high expectations every day, without the retreat into paperwork as substitute for teaching.

When people ask whether Collins can be replicated, they often mean: can her results be reproduced without her personality? But another way to ask the question is: what would it take to make her approach less exceptional? What if a system built schedules, class sizes, curriculum coherence, and teacher training around the premise that children deserve rigorous instruction and adults can provide it? Collins’s story is painful because it suggests that we often know what to do, but we structure schools in ways that make doing it feel impossible.

Her critics might say she proves nothing about public systems because she operated outside them. Her defenders might say she proves everything because she showed what children labeled as failures could do under a different set of expectations. Both claims oversimplify. Collins proved something narrower but still radical: that intellect is distributed more widely than opportunity, and that teaching—actual teaching, not supervision—can narrow the gap.

Death, and the work that remains unfinished

Marva Collins died in June 2015 at age 78. The obituaries and remembrances returned to the familiar elements: the school founded in 1975, the children written off, the discipline and Socratic questioning, the fame, the honors.

But an honest ending cannot be merely commemorative. Collins’s life leaves us with problems that have not been solved by her existence.

The first problem is how quickly we convert educators into symbols so that we can avoid the harder work of building conditions for widespread excellence. The second is how easily we turn rigor into a political weapon—either to shame public schools without funding them properly, or to romanticize “grit” while ignoring the structural violence that makes grit necessary. The third is how persistently race shapes which children are assumed to be capable of intellectual seriousness, and which adults are trusted to teach them.

Collins forced those problems into the open, sometimes deliberately, sometimes simply by refusing to behave in the ways expected of a Black woman teacher in a segregated educational economy. Her story is often told as a triumph over bureaucracy. It is also, more quietly, a story about sovereignty: a Black educator claiming the right to name what children are, and what they might become, without asking permission from institutions that had already decided.

In the National Humanities Medal materials, Collins is quoted declaring, “All children can learn,” and then sharpening it into something more personal: “If children fail, it’s about me, not them.” For a teacher, that is both a vow and a burden. It is also a challenge to the rest of us. If we believe she was right, then we cannot keep treating failure as the child’s property. We have to treat it as a diagnostic of adult choices—curriculum choices, policy choices, housing choices, funding choices, and the quieter daily choices of what we are willing to demand, and from whom.

Marva Collins made demanding look like love. She made excellence sound like a birthright rather than a prize. She also made clear how lonely that stance can be, and how quickly the nation that celebrates a teacher can turn, asking her not only to inspire but to certify an ideology.

In the end, her significance is not merely that she succeeded with some children in one place. It is that she exposed a set of American habits: our addiction to rescue narratives, our discomfort with Black authority, our tendency to confuse low expectation with empathy, and our willingness to call something a miracle rather than build it into policy.

If you want to honor Marva Collins honestly, you do not simply repeat her slogans. You take her at her word. You stop making excuses. You take responsibility. And you ask, with the seriousness she demanded in her classroom, why the kind of education she insisted was possible still feels, in so many communities, like an exception rather than the baseline.

More great stories

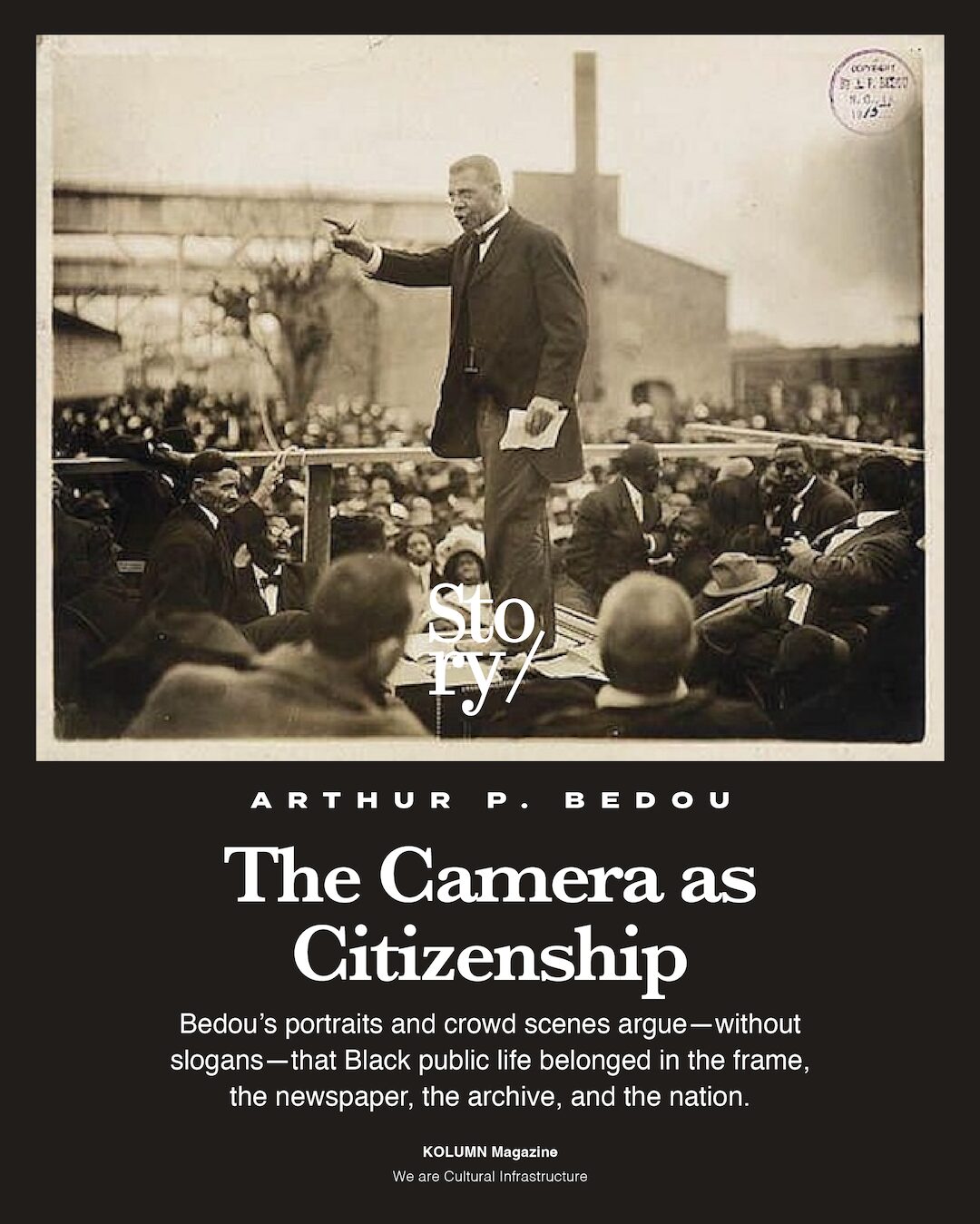

The Camera as Citizenship