The fight over how America consumes Black women’s intellect.

The fight over how America consumes Black women’s intellect.

By KOLUMN Magazine

The first time Sojourner Truth enters the public record, she does not arrive as a slogan. She arrives as a person—unsettlingly specific, stubbornly embodied, and difficult to simplify. Born Isabella Baumfree in Ulster County, New York, in the late eighteenth century, she came into a world where the law treated her as property and the language around her—Dutch, not English—was the tongue of people who owned human beings and named the terms of reality. The details matter because the country has often tried to flatten her into an uncomplicated emblem: a mighty voice, a headwrap, a single refrain. But the woman behind the emblem was complicated, strategic, spiritual, and sometimes contradictory in ways that make her more, not less, significant.

Even the most basic biographical facts resist neatness. Her birth year is commonly given as 1797, though the precise date is unknowable in the way enslaved people’s birthdates so often were: records were not kept because the system did not need enslaved people to have birthdays, only prices. What can be said with confidence is that she was born enslaved in New York—an origin that still surprises Americans who reflexively associate slavery with the South. She spent her childhood on the estates of Dutch enslavers, spoke Dutch first, and endured the early rupture that defines so many slave narratives: separation from parents, sale, and reassignment like furniture. As a child, she was sold away from her family, a transaction that fixed the brutality of slavery not as an abstraction but as a set of ordinary business decisions made by ordinary men.

Sojourner Truth’s life mattered not only because she survived these decisions, but because she learned how to speak back to them—how to take a system designed to silence and extract and repurpose its tools for her own ends. In her case, the tools were unusual: religious charisma, an instinct for the public stage, a shrewd understanding of how white audiences listened, and later, a modern grasp of image-making and fundraising. She became one of the nineteenth century’s most recognizable abolitionists and a relentless advocate for women’s rights, and she did it without formal education, without the conventional markers of elite leadership, and often without the protection of institutions that might have softened her edges.

But to understand her significance, it helps to treat her as more than a marble figure in a civic plaza. It helps to keep returning to the conditions that formed her: a Northern slavery system that relied on Dutch-speaking households; a gradual emancipation process in New York that produced confusing timelines of “freedom” that still bound Black families to white power; a religious environment where revivalism and prophecy could open doors that politics kept locked; and a reform culture—abolition, temperance, women’s rights—that was both emancipatory and deeply shaped by racial hierarchy. Sojourner Truth moved through all of this not as an ornament but as a force.

A childhood in Dutch New York, and the education of violence

The National Park Service biography captures the basic arc: Isabella Baumfree was born enslaved in Ulster County, spent her early years on the Hardenbergh estate, and was sold as a child to John Neely for $100 alongside a flock of sheep—an image so stark it feels composed, except it is the kind of administrative brutality slavery specialized in. She was beaten. She was terrorized. She was passed along. When Americans speak of “slavery” as if it were a single monolith, the details of Northern slavery tend to evaporate. Truth’s childhood insists that it did not just happen in plantations and cotton rows; it happened in New York households, in transactions recorded like livestock.

That Dutch first language shaped her later life in subtle ways. It complicates the popular stereotype embedded in the most famous version of her most famous speech, where she is rendered in a Southern dialect she did not naturally speak. It also points to a basic fact about slavery: it was not only a labor system, but a cultural system that forced the enslaved to learn the languages, customs, and social codes of the enslavers. In Truth’s case, this meant she learned to navigate white authority within a Dutch New York milieu—an experience that would later inform how she confronted, negotiated, and sometimes outmaneuvered white reformers who wanted her voice but also wanted to control what that voice said.

When she reached adulthood, Isabella was forced into relationships and motherhood under conditions that were not hers to choose. She married—some accounts say was made to marry—an enslaved man named Thomas, and had children. The often-repeated number “thirteen children” appears in later retellings of her speech, but the historical record more firmly supports fewer; this is one of many places where the legend accretes around the life. The larger truth remains: motherhood under slavery was both intimate and political. Children could be sold. Family could be broken. The law offered no real protection. These realities were not side notes for Truth; they became central to her moral authority.

In 1826 or 1827—sources vary in the precise framing—she left slavery. The New York legal process of gradual emancipation meant that “freedom” was not always a single moment; it was sometimes a shifting boundary, with enslavers exploiting loopholes and timelines. What remains clear is that she walked away, taking a young child with her, and attached herself to a household willing to offer some measure of protection. The story is often told as a simple escape. It is better understood as a negotiation with risk: leaving meant exposure to capture, violence, and economic precariousness, but staying meant the continued certainty of bondage.

The lawsuit that made her a legal pioneer

One of the most consequential acts of Sojourner Truth’s early freedom was not a speech. It was a lawsuit.

She pursued the return of her son—Peter—who had been illegally sold, and she fought for him through the courts. The significance of this is hard to overstate. A Black woman who had recently been enslaved took white men to court and won, forcing a legal system designed to uphold racial hierarchy to acknowledge her claim to her own child. This was not simply personal triumph. It was a demonstration that law could be contested, that rights could be asserted, and that freedom meant more than a change in labor status—it meant a fight over family, belonging, and the state’s role in sanctioning theft. It is also a reminder that abolitionist history is full of courtroom battles, not just moral arguments.

That victory foreshadows one of the throughlines of Truth’s later public life: she understood institutions as sites of struggle. She was not naïve about the limits of law, but she recognized that law, when forced, could produce enforceable outcomes. This stance—skeptical but strategic—will appear again when she advocates for Black soldiers, presses the federal government, and insists on material repair rather than rhetorical sympathy.

Religious awakening and the invention of “Sojourner Truth”

In 1843, Isabella Baumfree renamed herself Sojourner Truth. The name reads like a mission statement: “Sojourner” as traveler, “Truth” as message. It signaled her emergence as an itinerant preacher and reform lecturer, a woman who did not merely hold beliefs but carried them from town to town as a public vocation. That reinvention matters because the nineteenth century’s reform world was crowded with speakers, pamphleteers, and organizers—many of them white—and a formerly enslaved Black woman had to create a public identity that could command attention without institutional backing. The name did that work. It told audiences how to interpret her before she said a word.

Religion was not an accessory to her activism; it was a core engine. In the abolition movement, religious language often served as a shared vocabulary that could cross class boundaries and reach audiences who would not be moved by political theory. Truth used that vocabulary fluently. She framed slavery not only as injustice but as sin; she framed women’s rights not only as political necessity but as moral imperative. Her faith also granted her a kind of authority that white reformers sometimes struggled to rebut. A woman claiming divine mandate is harder to politely patronize.

The religious context also helps explain why Truth could stand in rooms full of hostile or skeptical listeners and still hold the stage. Revival culture valued testimony, moral certainty, and charisma—qualities she possessed in abundance. Where a conventional politician needed credentials, a preacher needed presence. Truth had presence.

The speech everyone knows—and the versions that complicate it

If Sojourner Truth were only a preacher and a legal pioneer, she would still be historically significant. But she became culturally immortal because of a speech delivered in 1851 at the Ohio Women’s Rights Convention in Akron—a moment that has been rewritten so many times it now functions as a test case for American memory.

The conventional version, the one most Americans can paraphrase, is built around a repeated question: “Ain’t I a woman?” In this telling, Truth confronts white feminists and male skeptics by pointing to her own laboring body—arms that have plowed and planted—and by demanding recognition of Black womanhood as fully womanhood. It is a brilliant argument, and it has shaped generations of feminist thought.

The problem is that the best-known version is not the earliest version. Scholars and archivists have long noted that the most famous transcription, published by Frances Dana Gage in 1863—twelve years after the speech—differs significantly from the account published closer to the event by Marius Robinson in 1851. The Sojourner Truth Project and the Women and Social Movements archive both lay out the differences plainly: Gage’s later version introduces the dialect, the refrain, and a set of details that appear nowhere in Robinson’s earlier report.

This does not mean Truth’s 1851 speech was insignificant. It means that what Americans call “Sojourner Truth’s speech” is partly a collaboration—perhaps an appropriation—between Truth’s performance and white editors’ desires. The question becomes: why did the later version become dominant?

Part of the answer is that slogans travel. “Ain’t I a woman?” is a portable line—short, provocative, easy to quote on a poster. The deeper answer is that America has often preferred Black women’s voices when they can be packaged into a form that flatters white audiences’ self-image. Rendering Truth in a Southern dialect she did not naturally speak could make her feel more “authentic” to Northern readers who expected a certain sound from formerly enslaved people. But it also subtly relocated her: it turned a Dutch-speaking New Yorker into a generic Southern slave figure, stripping away her specific origins and the Northern complicity those origins expose.

The argument over transcription is not academic nitpicking. It goes to the core of Truth’s significance: she was not only a speaker; she became a symbol, and symbols get edited. The tension between her lived complexity and the simplified legend is itself a lesson in how Black women’s histories are consumed.

This is also where it helps to read Truth through primary materials, not just famous excerpts. The Narrative of Sojourner Truth, first published in 1850 and expanded in later editions, was shaped by Olive Gilbert and later additions; it remains a foundational source for her life, offering correspondence, episodes, and the texture of her public work. The Library of Congress holds an important later edition, and Documenting the American South provides access to the earlier publication history, underscoring how her story circulated and evolved.

Abolition and women’s rights: An alliance, a friction, a fault line

Sojourner Truth’s presence in the women’s rights movement was always both catalytic and destabilizing. She forced white feminists to confront the limits of their own solidarity. When white women spoke of “womanhood,” Truth made the term do more work. She reminded audiences that “woman” was not a single category experienced the same way by everyone; it was filtered through race, labor, violence, and social protection—through who got helped into carriages and who got left to carry the weight.

This insistence did not always make her popular among reformers who wanted unity on their own terms. Abolitionist and women’s rights circles, while radical by the standards of their day, were still shaped by whiteness, class respectability, and the politics of who could be seen as a “proper” representative of a cause. Truth was frequently the most unforgettable person in the room, but she was not always the most welcomed. Her brilliance was that she could command attention anyway—sometimes by humor, sometimes by confrontation, often by an unanswerable moral clarity rooted in experience.

Her life also demonstrates that abolition and women’s rights were never cleanly separable projects. The same culture that argued Black people were naturally inferior argued women were naturally subordinate. Truth understood this intuitively and attacked the logic at its root. Her speech—whatever the precise wording—was built around a kind of empirical rebuttal: look at my body, look at my labor, look at my endurance. If your theories of weakness and dependency cannot account for me, then your theories are wrong.

The Atlantic, in an 1863 piece by Harriet Beecher Stowe, dubbed Truth “The Libyan Sibyl,” presenting her as a prophetic figure—half legend, half moral force. The piece is revealing not only for what it says about Truth, but for what it reveals about Stowe and the white reform imagination: admiration that can slide into exoticization, respect that can still frame a Black woman as mythic rather than fully ordinary-human. Truth became, even in her own lifetime, a figure onto whom others projected their needs.

Civil War work and the politics of freedom after emancipation

The Civil War era intensified the stakes of Truth’s activism. Freedom was no longer just a personal status; it was a national question backed by federal power, military policy, and postwar reconstruction. Truth supported the Union cause and worked to recruit Black soldiers—labor that placed her in the thick of the war’s moral argument: that the destruction of slavery required Black participation not only as victims but as agents of liberation.

But the war’s end did not resolve the deeper question Truth kept asking: what does freedom mean in practice? The abolition of slavery did not automatically produce land, safety, education, or economic stability. The Reconstruction era was full of promises and betrayals. Truth’s advocacy during and after the war belonged to a broader Black political tradition that treated emancipation as a beginning, not a finish line.

Her concern for material conditions shows up in the way she engaged with the federal government and with Black migration efforts. One can trace a line from her insistence on concrete outcomes—family reunification, wages, protection—to the later Black freedom struggle’s emphasis on civil rights and economic justice. Truth was, in this sense, an early architect of a framework many Americans still resist: rights are real only when they can be lived.

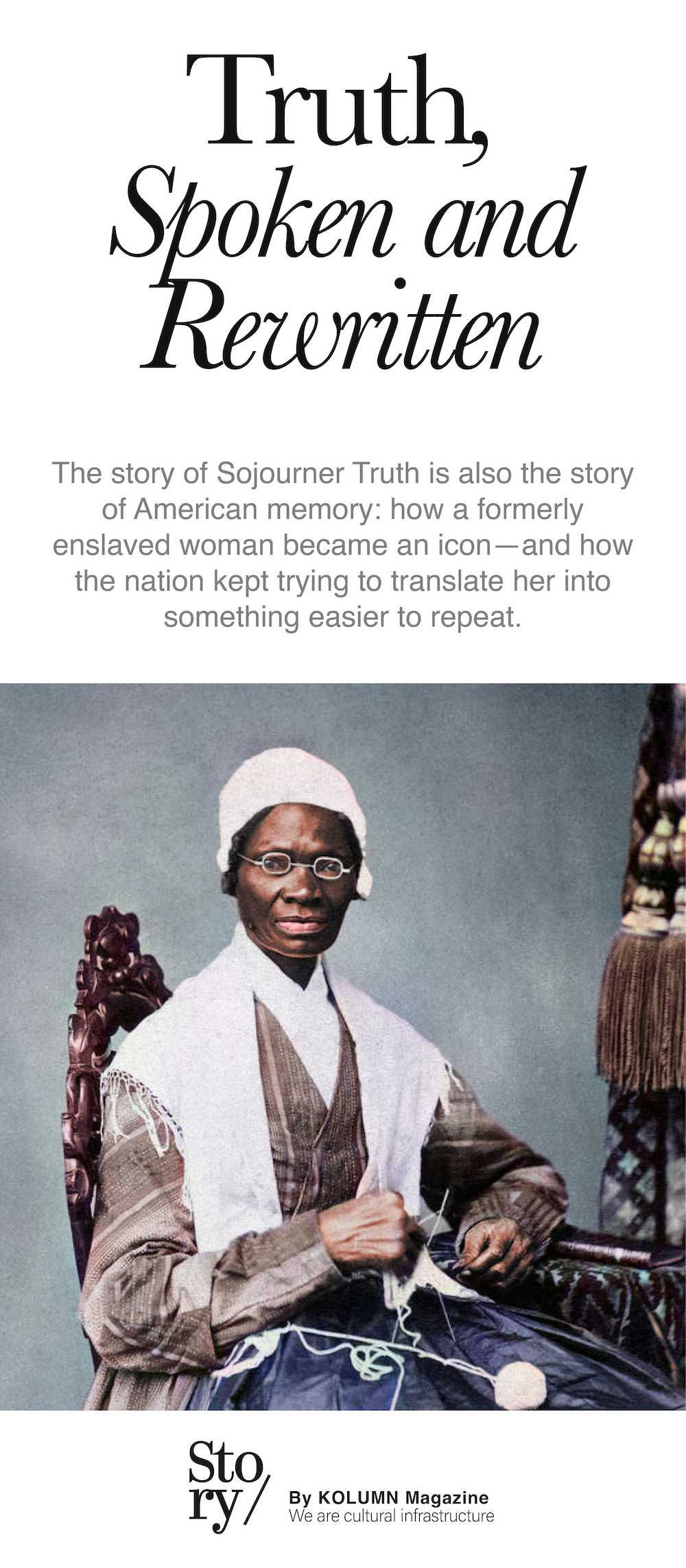

The modernity of her self-presentation

Sojourner Truth is often remembered as an orator, but she was also a master of nineteenth-century media. One of the most striking artifacts associated with her is her use of photography—carte de visite portraits sold to supporters—paired with the line often attributed to her: “I sell the shadow to support the substance.” The phrase captures her pragmatism. She understood that moral work required money, and money required strategy. She understood that images could travel farther than bodies, and that a dignified portrait could counter a culture determined to caricature Black people.

This matters for contemporary readers because it reframes her not as a premodern saint but as a sophisticated operator within the communication technologies of her day. She cultivated an image. She monetized it ethically to fund her work. She turned her own likeness into a revenue stream for activism. In an age of social media and movement branding, her tactics feel less like quaint history and more like a blueprint.

The contested icon and what we demand from our heroes

Every generation remakes Sojourner Truth. That remaking is partly tribute, partly appropriation. She appears in textbooks, murals, postage stamps, statues, and women’s history lists. But she is also repeatedly simplified into a single speech line—even when that line’s textual history is contested. The fight over “Ain’t I a woman?” is, in miniature, the fight over how America consumes Black women’s intellect: we often want their power without the complexity that produced it.

Recent public history efforts show both the appetite for her story and the ongoing need to correct the record. In May 2024, a new Sojourner Truth Legacy Plaza was unveiled in Akron at the site associated with the 1851 convention, commemorating her and embedding her memory in physical space—an acknowledgment that the nation’s landscape has too often honored the wrong people, or honored only a narrow slice of its heroes.

Meanwhile, historians and writers continue to revisit her life with fresh attention to faith, language, and the gap between the living woman and the symbol. Smithsonian Magazine’s 2024 feature underscores how much of her story remains underappreciated and how deeply religion shaped both her activism and her understanding of human dignity.

And Black publications keep situating her where she always belonged: not as an add-on to a white women’s movement, but as foundational to the tradition of Black feminist thought. Word In Black, for example, invokes her among the lineage of Black women’s political power and cultural leadership—part of a living genealogy, not a museum piece.

Why Sojourner Truth still matters: The argument she refused to stop making

Sojourner Truth’s significance is sometimes described in broad terms—abolitionist, feminist, civil rights pioneer. Those labels are accurate but incomplete. Her deeper importance lies in how she forced American ideals to encounter American reality.

She took the country’s own language—rights, womanhood, Christianity, freedom—and treated it as if it were meant literally. She insisted that if the nation claimed human equality, it had to account for Black women’s bodies and lives, not just white men’s political theories. She demonstrated that faith could be a radical instrument, not merely a private consolation. She modeled a politics rooted in lived experience without abandoning strategy. And she exposed, again and again, how reforms that ignore race reproduce hierarchy under a new name.

If you want to understand why her voice still echoes, listen to the core structure of her challenge. It is not only “don’t exclude me.” It is “your categories are broken.” If womanhood depends on delicacy, what do you do with women who have labored like men because the world gave them no choice? If freedom is declared but families can still be ripped apart, what does freedom mean? If Christianity is invoked to justify hierarchy, whose Christ is that?

These are not nineteenth-century questions. They are ongoing ones—visible in debates about voting rights, reproductive autonomy, labor exploitation, racialized violence, and the thin line between symbolic recognition and material justice.

In contemporary America, “memory” often substitutes for repair: a statue instead of restitution, a proclamation instead of policy. That substitution is precisely the kind of move Truth spent her life resisting. And it is why her story sits naturally beside modern arguments over accountability and remedy—arguments that surface, for example, in public reckonings with racial terror and its afterlives. A Tulsa-focused commission update written in 2023 captures this ongoing tension between rhetoric and remedy, emphasizing how calls for justice persist long after the cameras move on—a dynamic Truth would have recognized instantly.

Sojourner Truth never allowed the country to pretend its ideals were self-executing. She understood that rights have to be claimed, fought for, enforced, and funded. She understood that language can be weaponized—and that the person who controls the transcript can control the legacy. She also understood something that remains unnervingly contemporary: that even when you win the argument, the world will try to rewrite what you said.

Her life, then, is not merely inspirational history. It is instruction. It teaches that freedom is not a moment but a practice; that public speech is power and therefore contested; that the most radical act may sometimes be insisting, in a room full of people who would rather not hear it, on the plain fact of your humanity.

More great stories

Behold, Dallas