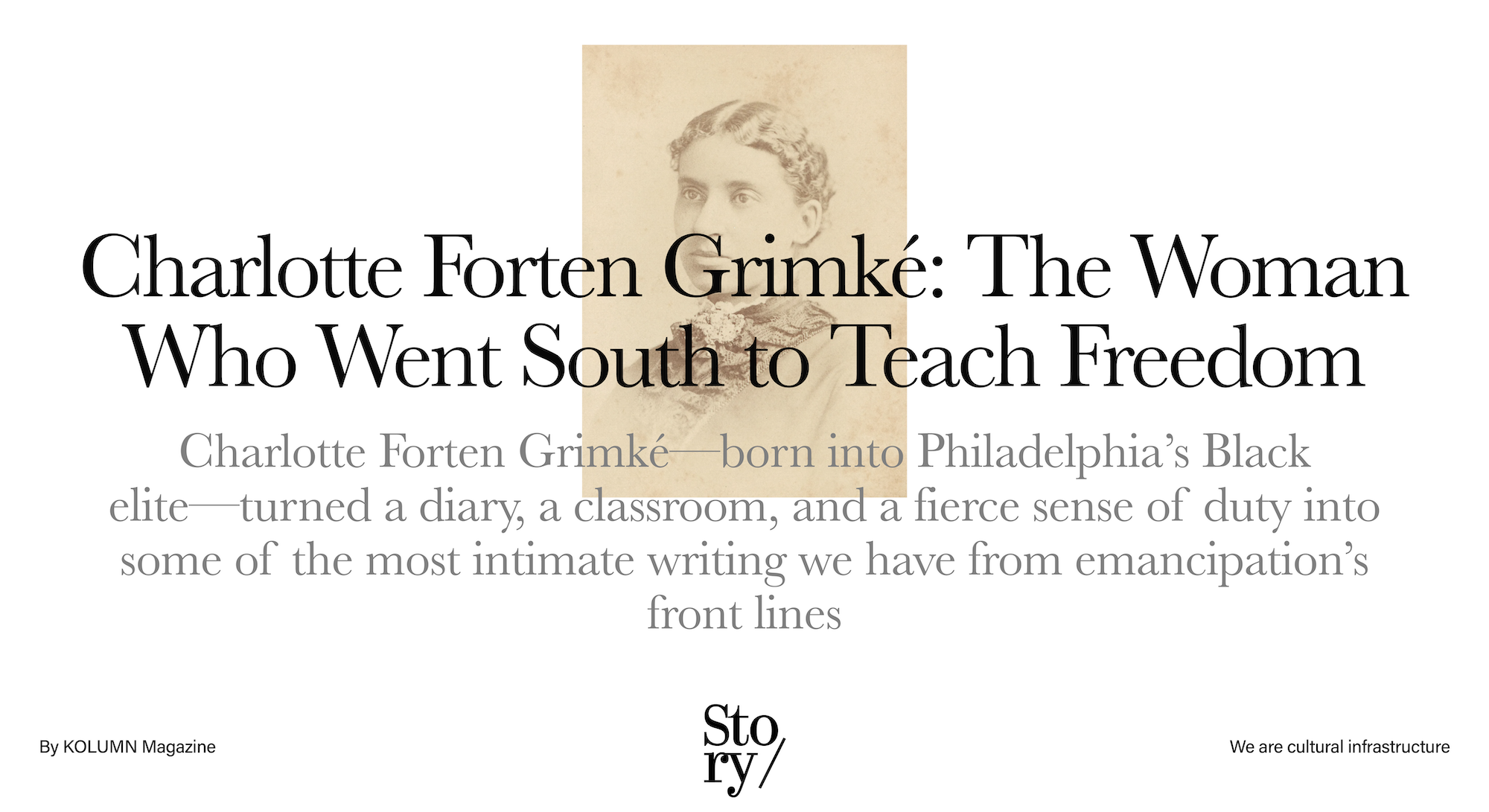

In a country that trained itself to disregard Black women’s inner lives, Charlotte Forten Grimké insisted—quietly, relentlessly—that her mind belonged to history.

In a country that trained itself to disregard Black women’s inner lives, Charlotte Forten Grimké insisted—quietly, relentlessly—that her mind belonged to history.

By KOLUMN Magazine

In the long ledger of American freedom, there are names that arrive with the clang of public ceremony—generals, presidents, orators—figures who seem to stride onto the page already monumental. Charlotte Louisa Forten Grimké enters differently. She comes to us in sentences written late at night, in the private negotiations of a young woman trying to become herself in a country designed to prevent exactly that. She comes to us through the work of a teacher—often romanticized as “calling,” too often minimized as “only teaching”—performed in classrooms that doubled as proving grounds for emancipation. And she comes to us, crucially, as a Black woman intellectual in the nineteenth century whose record of thought and feeling is so detailed that it still startles: the discipline of study, the ache of isolation, the pressure of respectability, the terror and promise of political change, the moral thrill of doing what history demands.

Forten Grimké is sometimes introduced as a writer—she published poems and essays, most famously her two-part Atlantic account of teaching in the South Carolina Sea Islands during the Civil War. But the spine of her life is education: the education she had to fight to obtain, the education she delivered under conditions that tested the meaning of the word, and the education she continued to practice in the broadest sense—organizing, mentoring, convening, and arguing for a more honest democracy.

To tell her story well is to resist two temptations. The first is to flatten her into a symbol—the “first” this or the “pioneering” that—until the complicated person disappears behind a plaque-worthy sentence. The second is to treat her privilege as disqualifying, as if being born into an eminent free Black family in Philadelphia makes her less representative or less brave. Forten Grimké’s life, in fact, is one of the clearest demonstrations of what privilege could and could not protect in America. It gave her access to books, to tutors, to circles of reform. It did not spare her from racism, loneliness, illness, or the constant psychic labor of living as an exception in spaces that treated Black presence as a problem to be solved.

A childhood built on abolition—and guarded by it

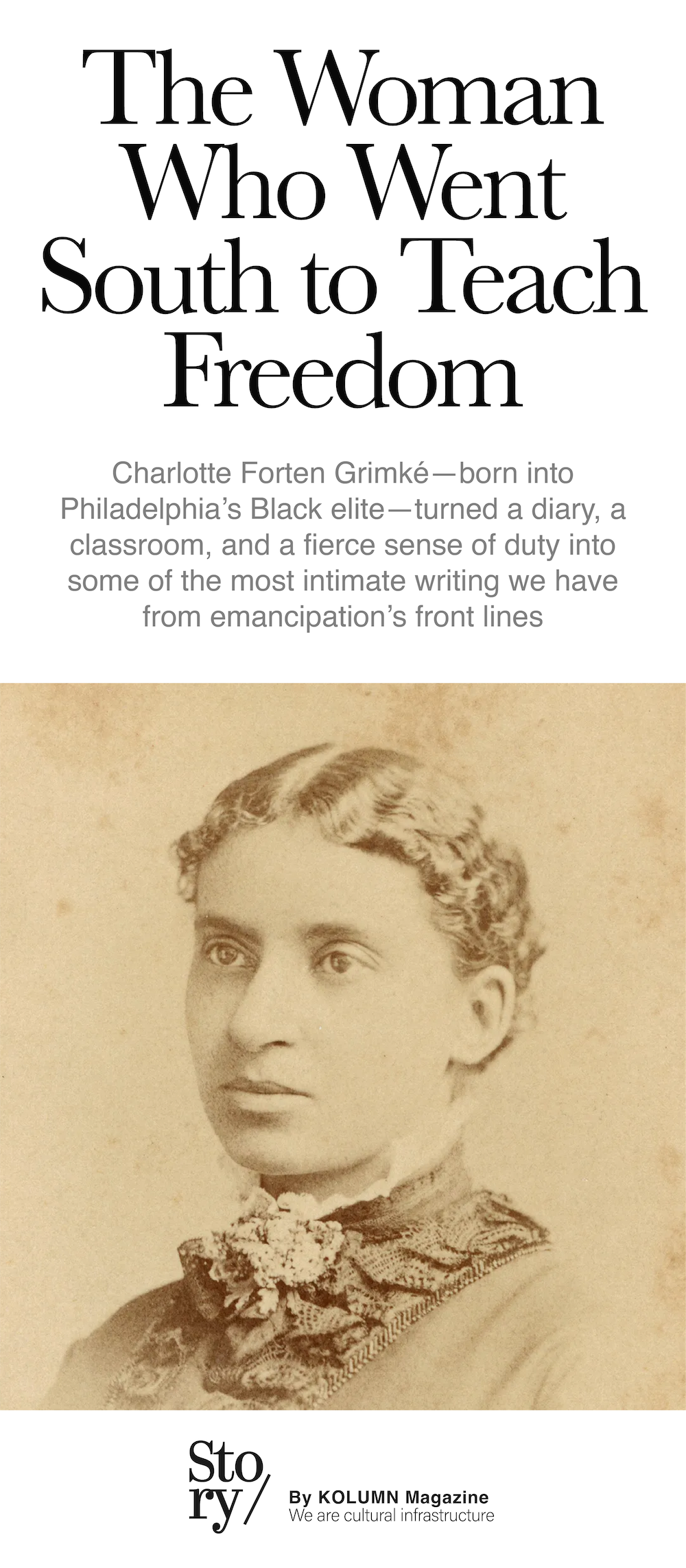

Charlotte Forten was born in Philadelphia in 1837, free, into a family whose name already meant something in the city’s Black community and, increasingly, in the nation’s abolitionist network. Her lineage mattered not as pedigree for its own sake, but because it represented a sustained argument against slavery and racial caste: the Fortens were builders of institutions, funders of organizing, and exemplars of Black civic leadership in an era that treated Black citizenship as an impossibility.

Her upbringing was shaped by the double consciousness of free Black elites in the antebellum North: the insistence on cultivation—literacy, music, languages, comportment—paired with the knowledge that no accumulation of refinement could fully insulate a Black person from a white supremacist order. Forten’s later diaries would return again and again to the tension between aspiration and constraint, between the hunger to be “useful” and the fear of failing those who invested so much in her.

When she was still a teenager, she began keeping the journals that would become one of the richest first-person records we have from a nineteenth-century Black woman moving through Northern intellectual life and into the Civil War’s upheavals. The very act of recording mattered. Diary-keeping was a discipline—self-surveillance, self-fashioning, and, at times, self-rescue. In her earliest entries, she describes the impulse plainly: she wants “some remembrance” of her own life, even if it might seem “unimportant to others.” That phrase is less modesty than prophecy; she understood the likelihood that a Black woman’s inner life would be deemed negligible unless she insisted, line by line, that it was not.

Salem: The making of a teacher and a writer

Philadelphia could nourish and constrain. For further education, Forten was sent to Salem, Massachusetts—a move that exposed both the possibilities of integrated schooling and the sharp edges of Northern prejudice. Salem mattered in Forten’s life in ways that go beyond résumé milestones. It was where she trained in the methods of teaching and absorbed the culture of New England reform; it was also where she experienced the social isolation that would become familiar: being watched, evaluated, and sometimes patronized by white peers who could applaud her “exceptionalism” while still refusing genuine equality.

Salem State University’s institutional memory names her as its first African American graduate (then the Salem Normal School), situating her inside a profession that was rapidly expanding for women even as it remained racialized in access and status.) Normal schools—teacher-training institutions—were engines of nineteenth-century educational reform, and Forten’s training put her at the crossroads of pedagogy and politics. She was not simply learning to manage a classroom; she was preparing to enter one of the few “respectable” professions open to women and, in her case, to do so as a racial representative under constant scrutiny.

She taught in Salem in the 1850s, an early chapter that already hints at the fragility of her health and the persistence of her ambition. Biographical accounts note recurring illness, including tuberculosis, that disrupted her teaching and forced periodic returns home. The interruptions mattered: they complicated any tidy narrative of linear progress and remind us how often nineteenth-century Black women’s public work was shaped by private physical cost.

Yet even when her health faltered, her mind pressed forward. She wrote poetry and published in abolitionist outlets; her journals show a young woman reading intensely, attending lectures, and tracking the nation’s political crisis as it accelerated toward war. She belonged to a generation that came of age under the shadow of the Fugitive Slave Act and the violence of slavery’s expansion, and she recorded the emotional weather of that era: dread, anger, determination, spiritual searching.

Choosing the Sea Islands: “Experiment” becomes lived reality

When the Civil War began, “freedom” was not yet policy; it was a battlefield condition. The Union occupation of the Sea Islands—particularly around Port Royal, South Carolina—created a new and volatile landscape. Planters fled, enslaved people remained, and Northern officials, missionaries, and teachers arrived to test whether formerly enslaved communities could be organized into free labor, schools, and self-governance. This became known as the Port Royal Experiment, and it was there that Charlotte Forten Grimké made one of the defining decisions of her life: she went South to teach.

Her arrival placed her in a rare position. The National Park Service describes her as a prominent educator and activist and emphasizes her work teaching newly freed people on the Sea Islands during the war. Another NPS biographical entry notes that she was the first Black teacher to arrive on the Sea Islands after Federal occupation—an “only” that should not be romanticized but should be understood as risk. In 1862–64, the South was not merely hostile territory; it was a place where Black autonomy—especially a Black woman’s autonomy—could be met with violence, contempt, or bureaucratic sabotage.

Forten’s choice also complicates our understanding of Northern Black life. Too often, emancipation narratives treat Black Northerners as distant spectators to slavery’s collapse. Forten was not a spectator. She entered a war zone to do intimate work: to teach children and adults who had been legally forbidden to learn, to translate “freedom” into daily practice, to witness the cultural power of people who had survived the plantation regime and were now being asked to survive “free labor” regimes and Northern benevolence alike.

The classroom as a frontline

In her Atlantic essays—published as “Life on the Sea Islands” in May and June 1864—Forten offered Northern readers something they rarely received: an account of emancipation centered not on white policymakers or military leaders but on the lives, labor, and community practices of freedpeople themselves. She described the daily textures of teaching: attendance shaped by labor demands, children arriving with uneven preparation, adults hungry for literacy, and the constant improvisation required to build a school where slavery had worked for generations to destroy the very idea of Black education.

Her writing does not read like propaganda. It is observant, frequently tender, sometimes critical, and always aware that the so-called “experiment” was being watched by skeptics looking for proof that Black freedom would fail. That pressure—proving capacity under surveillance—mirrored the pressure she had long felt in Northern classrooms, but in the Sea Islands it expanded: the performance of freedom itself was under evaluation.

PBS’s profile of Forten underscores that her Atlantic publication brought the work of the Port Royal Experiment to the attention of Northern readers. The point is not merely that she “raised awareness,” as contemporary shorthand might put it. The point is that she translated a contested social reality into narrative—argument, witness, evidence—at a moment when public opinion could influence whether Reconstruction would be an investment or an abandonment.

It is also in these writings and related scholarship that Forten emerges as an early recorder of Black spirituals. Accounts emphasize that she transcribed Sea Island hymns and spiritual practices, preserving cultural expression that slavery tried to suppress and that Northern observers often misunderstood. Her attention to music and worship was not an aside; it was recognition that education was never only about letters, that a people’s songs and religious life carried intellectual and moral knowledge too.

The cost of witness

Forten’s Sea Islands period is often summarized as two years of courageous service. That’s true as far as it goes, but it risks erasing the toll. She was living amid war, disease, and relentless responsibility. Her health, already precarious, deteriorated, and she returned North. If emancipation is sometimes narrated as a rising arc, Forten’s life insists on something messier: freedom work can exhaust the body, and public virtue does not immunize anyone against private collapse.

Still, she did not leave the Sea Islands behind. She took the experience with her into print, and through print she extended the classroom. Her essays became part of how the North imagined the South’s transformation, and they remain, for historians, primary documents that complicate easy myths about Reconstruction benevolence.

Washington, D.C.: Marriage, ministry, and movement building

In the decades after the war, Forten Grimké’s life moved into another crucial American arena: Washington, D.C., a city where Black political aspiration and white backlash coexisted in close proximity. She eventually married Francis J. Grimké, a prominent Presbyterian minister at the Fifteenth Street Presbyterian Church—an influential Black congregation whose members included leaders of the capital’s Black community. Their marriage joined two storied lineages: the Fortens of Philadelphia abolitionism and the Grimkés linked to the famous white abolitionist sisters Sarah and Angelina Grimké, and to the complex interracial history of slavery in South Carolina.

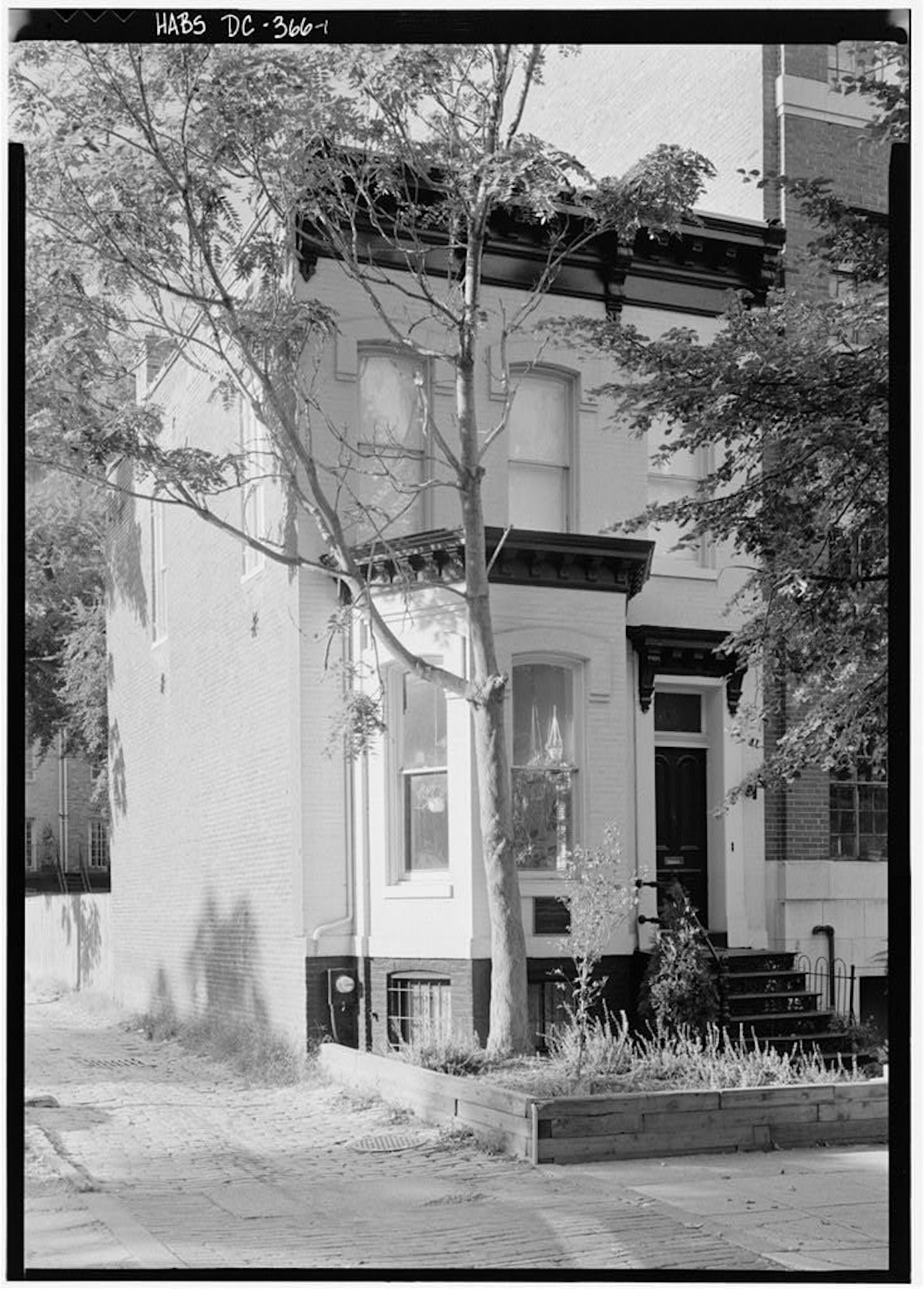

The marriage also made Forten’s public life both more visible and, in some ways, more circumscribed by expectations of a pastor’s wife. The NPS entry on her Washington residence notes that she lived in Dupont Circle in the early 1880s. In that setting, her work often took the form of organizing within and around the church—building networks of charity, education, and “racial uplift” efforts that were not merely social but political in their implications.

Her private life also held grief. She gave birth to a daughter, Theodora, who died in infancy. The loss punctures any temptation to treat her as a figure made entirely of resolve. Her journals—continued later in life—carry the record of ambition alongside sorrow, a reminder that public contribution does not cancel human vulnerability.

The diaries as an accomplishment, not an artifact

If Forten Grimké had done nothing but teach in the Sea Islands, she would deserve remembrance. If she had done nothing but publish “Life on the Sea Islands,” she would still hold a place in American letters. But her diaries—the sustained practice of recording thought across decades—constitute a major accomplishment in themselves.

Encyclopaedia Britannica describes her as an abolitionist and educator best known for the diaries she wrote, later published posthumously. That phrasing can make the diaries sound like a passive legacy, as if they simply survived and were later “discovered.” In reality, they were produced with intention, craft, and perseverance, and they offer what public records rarely provide: interiority.

They also challenge what counts as “political writing.” Forten’s journals include accounts of lectures attended, books read, people met, humiliations endured, and resolutions made. This is politics in the deeper sense: the formation of a citizen under siege, the ethical arguments built inside a person who understands that her own life will be used as evidence for or against her people. When she writes about striving for self-improvement, she is not merely repeating Victorian moralism; she is registering the racialized demand that Black excellence must be constant to be legible at all.

Modern editors and scholars have treated these journals as foundational texts for understanding Black women’s intellectual history. The American Revolution Museum’s discussion of her journal points readers toward the edited volumes and emphasizes her significance as poet and educator within the Forten family legacy. Even the existence of multiple editions—mid-century publication and later edited compilations—signals the breadth of scholarly recognition: these are not quaint personal notes but a historical archive.

Against the myth of the “good North”

One of Forten Grimké’s enduring contributions is how clearly she undermines the comforting binary of a racist South and enlightened North. Her life and writing show that Northern spaces could offer education while still enforcing exclusion; could celebrate abolition while still practicing discrimination; could welcome Black talent while denying Black belonging.

This is why she remains so valuable to contemporary readers. She does not let the nation off the hook by locating injustice only “elsewhere.” Her story threads Philadelphia, Salem, South Carolina, and Washington into a single map of American contradiction.

Even sources not centered on her biography catch this. A Washington Post feature on D.C. authors notes her move to Washington after teaching in South Carolina and emphasizes her best-known work and diaries—framing her as a local literary figure who “should be better known.” That casual line—half admiration, half lament—echoes a larger truth: Forten Grimké has often been treated as an important supporting character in Reconstruction history rather than as a principal. The record suggests otherwise.

A career that refuses a single genre

It is tempting to categorize Forten Grimké by one role—teacher, diarist, abolitionist, poet. Her life resists that simplicity because the nineteenth century demanded that Black women practice multiplicity to survive and to lead. She taught, yes, but she also served as a cultural intermediary, translating the realities of freedpeople to Northern audiences and translating Northern institutions back into terms that could serve Black communities.

Her writing ranges from the documentary realism of her Sea Islands essays to poetry and later recollective prose. She participated in networks of reform that included women’s rights advocacy and community organizing, and her Washington years linked her to an influential Black public sphere shaped by churches, clubs, newspapers, and professional associations

This is one reason her work fits so naturally into the current revival of interest in Black women’s intellectual history. She offers a bridge between eras—antebellum organizing, wartime transformation, Reconstruction hopes, and the long late-century entrenchment of segregationist ideology. She lived long enough to see the nation retreat from Reconstruction’s promises, and her life stands as a reminder that “progress” in America has often been followed by organized undoing.

The legacy: What she left, what she still asks

Charlotte Forten Grimké died in 1914, but her questions are still among the most American: What does freedom require beyond legal declaration? What does education mean when it is delivered inside inequality? What is the responsibility of the relatively protected to those made vulnerable by design? And how do you record a life when you know the archive was not built for you?

Her answers were not delivered as manifestos. They were delivered in choices: to pursue education despite exclusion; to teach despite illness; to go South despite danger; to write despite the likelihood of being ignored.

They were also delivered in craft. “Life on the Sea Islands” remains a masterclass in witness writing—precise in observation, careful in portrayal, attentive to the humanity of people who had been reduced, by law and custom, to property. The journals remain a masterclass in interior history—the kind that helps us understand not only what happened, but what it felt like to live through it.

And that may be her most radical accomplishment. In a country that trained itself to disregard Black women’s inner lives, Charlotte Forten Grimké insisted—quietly, relentlessly—that her mind belonged to history.

More great stories

The Camera as Citizenship