Keep hope alive” was never meant to be decorative. It was a command to outlast cynicism, to organize anyway, to build coalitions where the American culture preferred divisions, to push institutions that move only when pushed

Keep hope alive” was never meant to be decorative. It was a command to outlast cynicism, to organize anyway, to build coalitions where the American culture preferred divisions, to push institutions that move only when pushed

By KOLUMN Magazine

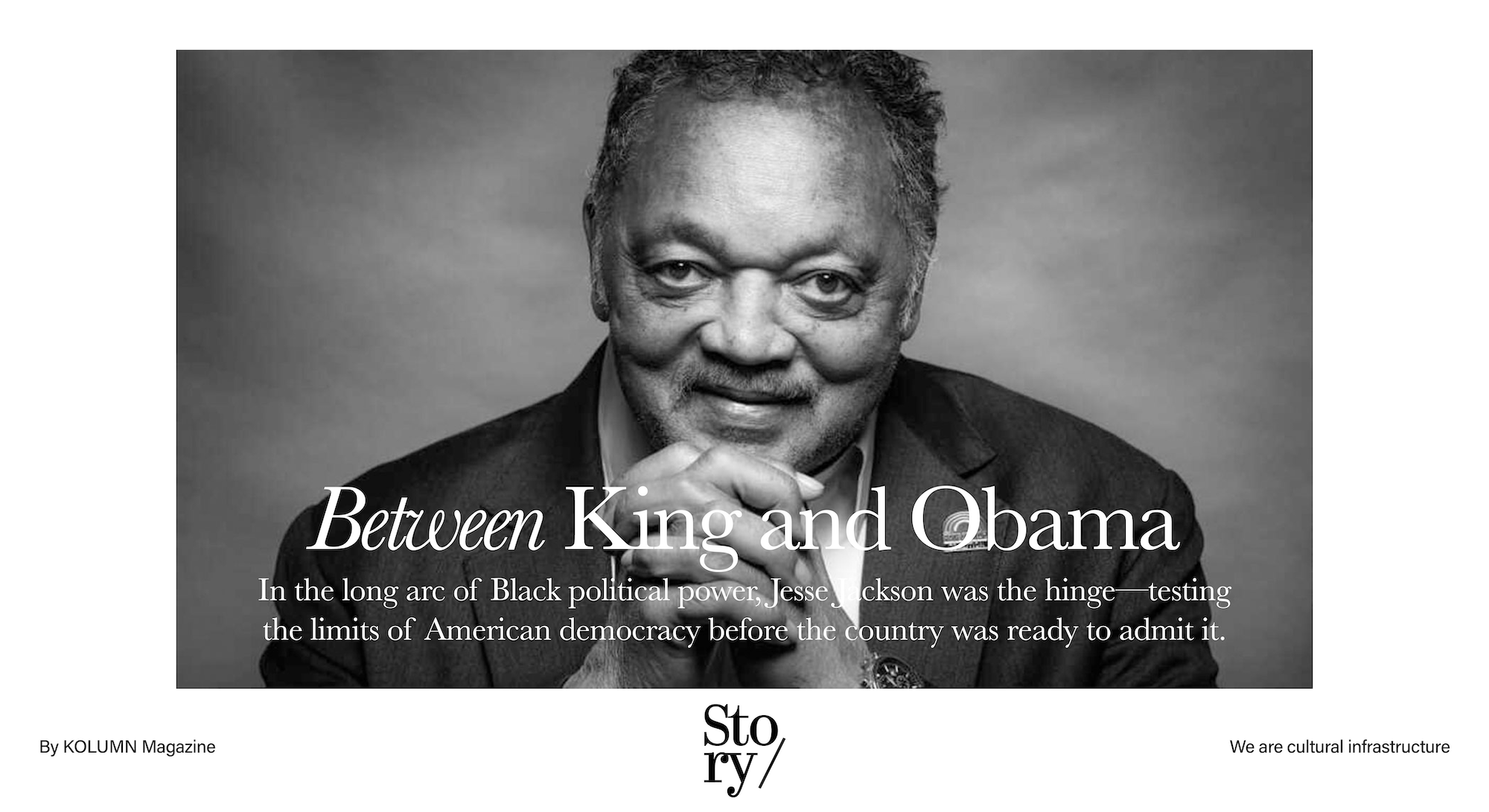

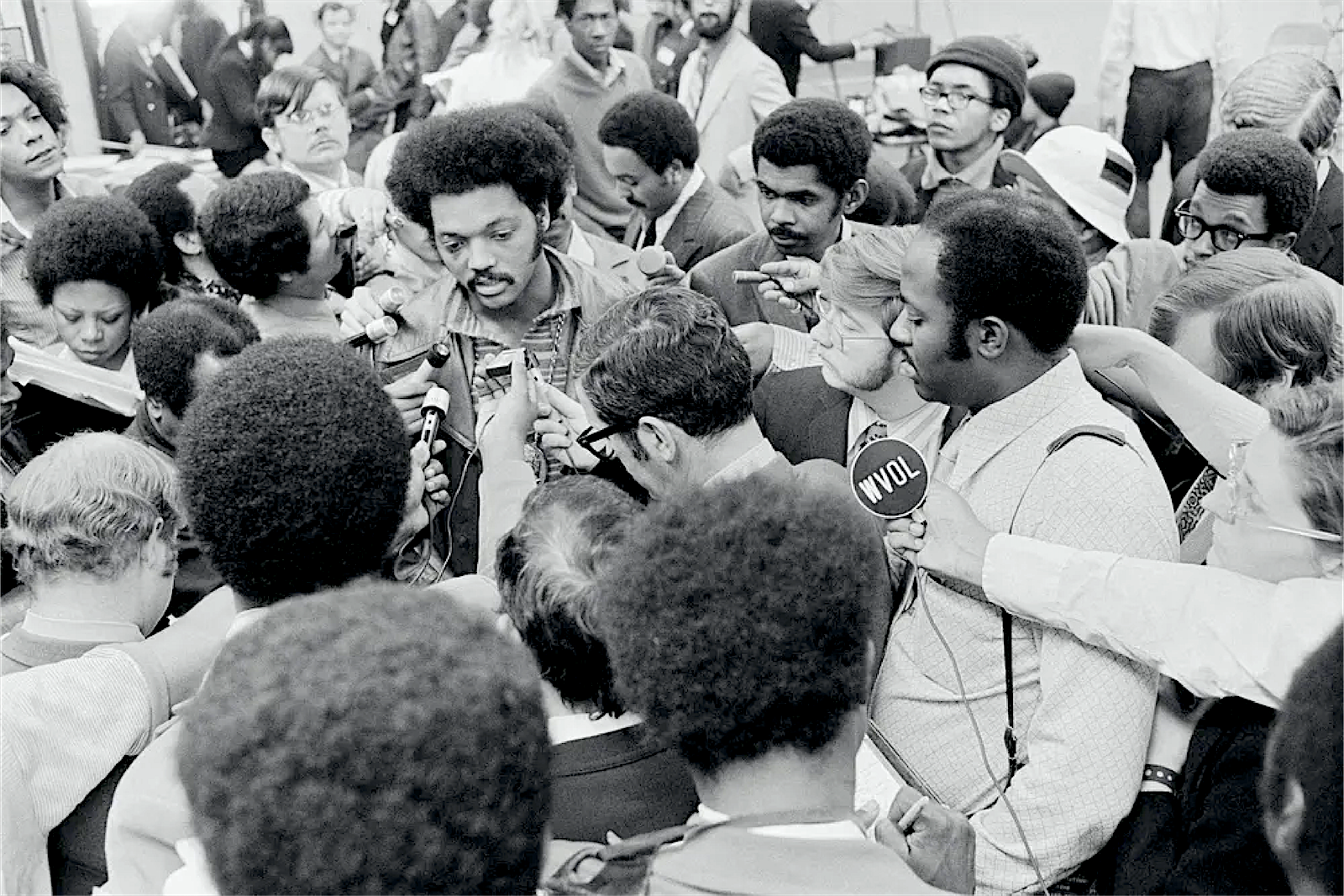

Earlier today, after Jesse Jackson died at 84, the tributes arrived in the language America reserves for its most persistent persuaders: trailblazer, icon, civil-rights giant. Reuters, citing NBC News, reported his death and framed him as a prominent civil-rights leader and Baptist minister whose national influence extended well beyond the movement’s classic era. The Washington Post called him a leading African American voice on the global stage—an organizer who marched in Selma and Memphis, then launched two historic presidential campaigns that changed the political grammar of the Democratic Party.

Those summaries are accurate as far as they go. They are also incomplete.

Jackson’s life—public, photographed, sermonized, debated on cable news, whispered about in back rooms—never fit a single genre. He was a minister whose pulpit extended into boardrooms. A protester who became a candidate. A coalition-builder whose sharp elbows sometimes bruised the alliances he sought to hold together. A moral spokesman who often spoke in the practical dialect of leverage: boycotts, voter drives, corporate commitments, negotiated releases. A man who seemed to believe that American democracy could be shamed into improvement, pressured into reform, and, if necessary, out-organized.

To tell Jesse Jackson’s story honestly is to resist a simple verdict. It is to follow the arc from the segregated South to the bright lights of national politics—and to linger in the contradictions. His admirers saw a bridge between Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s movement and a new era of multiracial politics. His critics saw a performer, a provocateur, a rising generational voice against long-standing challenges to a fully functional democracy for all. Both perceptions drew strength from real episodes, real speeches, real harm and real progress.

What is certain is that for more than half a century, Jackson helped set the terms of American public argument about race, poverty, jobs, war, and belonging. He did it by refusing to accept the limitations the country handed him—limitations on who could run, who could speak for whom, which issues counted as “electable,” which communities were expected to wait their turn.

In that refusal sits his historical significance.

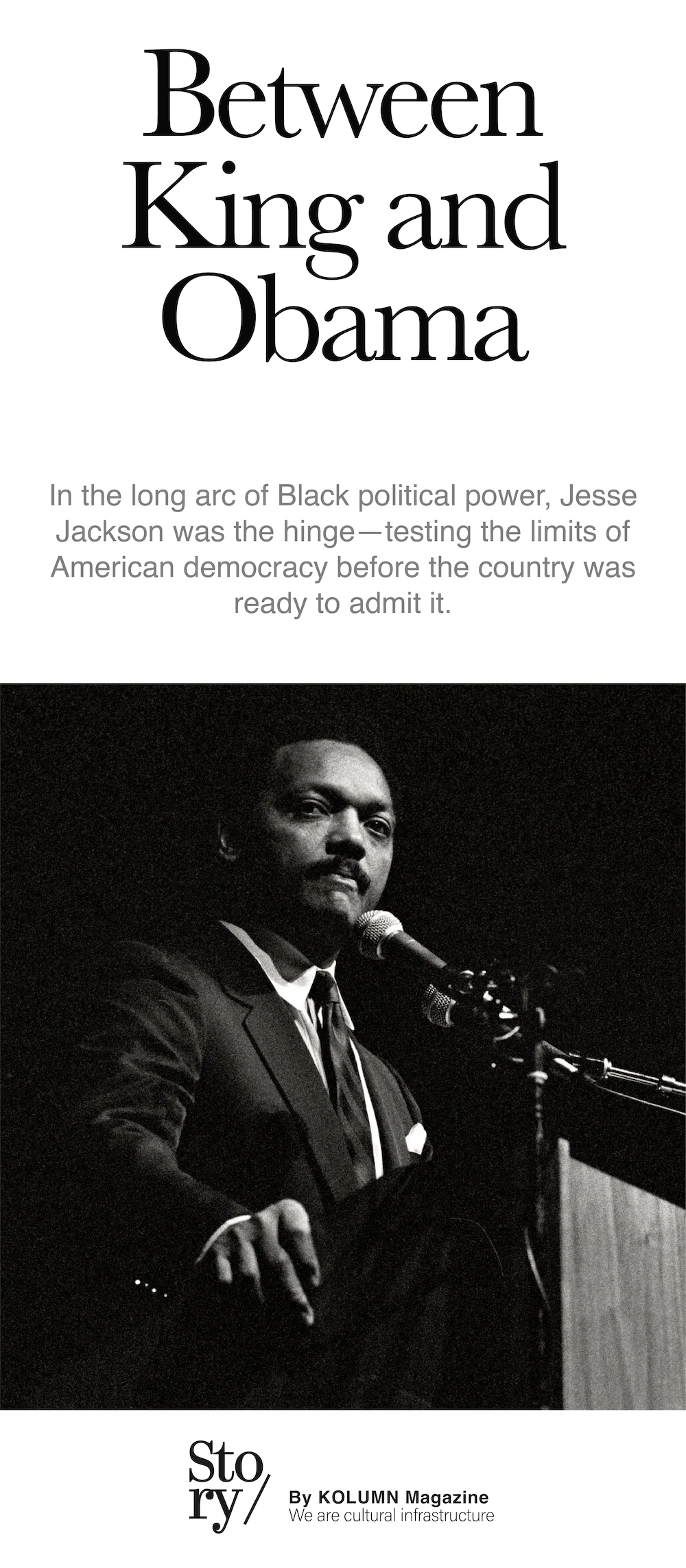

A childhood in the segregated South, a voice made for the public square

Jesse Louis Jackson was born in Greenville, South Carolina, in 1941, growing up in a world ordered by segregation and enforced by both law and custom. That origin matters not as a cliché but as a formative reality: the South that shaped him was one where a Black child learned early that citizenship was conditional, and that the promise of the Constitution was filtered through local power. Even later profiles and biographical summaries—written with the calm hindsight of encyclopedias—stress that he rose from those beginnings to become one of the most recognizable civil-rights leaders of the 20th century.

In Greenville and beyond, Jackson developed two gifts that would define his life: language and presence. He became an orator with a preacher’s rhythm and a politician’s timing, capable of lifting an audience with a single repeated phrase, and capable, too, of weaponizing a sentence so that it landed as pressure. His later slogan—“Keep hope alive”—worked because it sounded like both a benediction and an instruction. It asked for endurance; it also demanded action.

The early chapters of his activism often get summarized as “student protests” or “civil-rights involvement,” which risks minimizing the actual courage required for even small acts of defiance. Rainbow PUSH’s own institutional biography recounts Jackson’s activism as a student desegregating a public library and helping lead sit-ins, then moving into full-time organizing in 1965 with the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. It is an origin story that places him inside the organizational bloodstream of King’s movement, not merely adjacent to it.

The Stanford King Institute, in its profile of Jackson, underscores the link: he rose within the orbit of King and the SCLC, and later translated that training into an independent political project. The significance here is not just proximity to greatness. It is that Jackson learned how a movement is built: through local chapters, mass meetings, disciplined messaging, and the hard, unglamorous logistics of turnout.

In other words, he learned how to make moral claims operational.

Operation Breadbasket: Economic justice as civil rights

Jackson’s national prominence accelerated through Operation Breadbasket, the SCLC’s economic program aimed at expanding Black employment and business opportunities. While many Americans remember the movement through the imagery of lunch counters and marches, Breadbasket insisted that equal rights were inseparable from economic power—jobs, contracts, ownership, and leverage in consumer markets.

Rainbow PUSH’s biography notes that King appointed Jackson to direct Operation Breadbasket, placing him at the center of a strategy that treated corporate behavior as a political battlefield. This emphasis—economic justice as civil rights—would become Jackson’s signature. It also set him on a path toward conflict within the movement’s established leadership, because the tools Breadbasket used—boycotts, negotiations, metrics about hiring—often required a different style of leadership than the charismatic moral appeals associated with King.

After King’s assassination, the movement’s internal debates sharpened. Jackson emerged as one of the figures determined to carry forward King’s unfinished economic agenda, but on his own terms. The result was a pivot that would define the next fifty years of his public life.

Operation PUSH: Building a pressure organization in Chicago

In 1971, Jackson founded Operation PUSH—People United to Serve Humanity—an organization aimed at improving Black economic conditions and expanding opportunity through direct pressure on institutions. Chicago became his laboratory: a place where he could test whether boycotts and negotiations could turn consumer power into jobs, contracts, and concrete commitments.

Operation PUSH is often described as an economic justice organization, but its deeper purpose was political education: teaching communities that they had leverage, and teaching corporations and politicians that Black consumers and voters were not a demographic to be managed but a constituency to be answered to. A Cambridge reference summary situates PUSH as a project pledged to fulfill King’s dream of eliminating poverty and securing racial equality—explicitly tying Jackson’s post-King work to King’s final priorities.

What made PUSH distinct was its blend of the sacred and the strategic. Jackson framed economic demands in moral terms—justice, dignity, fairness—while also pursuing measurable outcomes: hiring targets, supplier diversity, and negotiated agreements. The approach drew supporters who were tired of symbolic victories, and critics who worried about coercion, transparency, and the temptation for organizations built on pressure to slip into personality cults.

Both reactions had precedent. Any movement that learns to make power negotiate eventually faces questions about how it uses the power it accumulates.

The Rainbow Coalition: A theory of American politics before it was fashionable

If Operation PUSH was Jackson’s mechanism, the Rainbow Coalition was his theory.

In 1984, Jackson founded the National Rainbow Coalition, a social-justice organization that aimed to assemble a multiracial, multiethnic political alliance—Black voters, white progressives, labor, farmers, Latinos, Asian Americans, LGBTQ+ communities, and others—into a governing coalition rather than a protest audience. The phrase “rainbow” was both branding and argument: that America’s excluded groups, treated separately, could be ignored; together, they could demand policy.

Similar accounts later described the Rainbow Coalition as a strategy to unite a multicultural group of Americans through Jackson’s 1984 presidential run, treating it as an early blueprint for the diversity language that would become mainstream decades later. But in the 1980s, the idea was risky. Party elites often treated “coalition” politics as code for fragmentation, and treated Jackson’s constituency as inherently unelectable. Jackson insisted the opposite: that the electorate itself was changing, and that the party’s future required acknowledging the nation it claimed to represent.

The Stanford King Institute credits his 1984 campaign with helping register a million new voters and winning millions of votes, evidence that his coalition wasn’t merely rhetorical. And by 1996, the Rainbow Coalition and Operation PUSH merged into what became the Rainbow PUSH Coalition, formalizing Jackson’s twin strategy: organize the grassroots and pressure the institutions.

This institutional consolidation—activism fused with a political infrastructure—was one of Jackson’s lasting contributions. It offered a model for how movement energy could become durable, even if its founder aged or stepped back.

The presidential runs: Losing elections, winning terrain

Jackson’s bids for the Democratic presidential nomination in 1984 and 1988 are frequently framed as symbolic runs: historic, inspiring, but ultimately doomed. That reading misses what the campaigns accomplished and why they matter.

In 1984, Jackson’s campaign did not win the nomination, but it forced the party to confront a reality it preferred to dodge: a Black candidate could assemble a serious national constituency, compete in primaries, and shape the platform conversation. The Stanford King Institute’s summary emphasizes the scale—millions of votes—and the voter registration impact. His 1988 run went further: Jackson won multiple primaries and caucuses before losing the nomination to Michael Dukakis.

What did that change?

First, it widened the imagined boundaries of who could plausibly lead. Time magazine, in 1988, captured the cultural shock: the presidency as “reserved” for white men was an adult truth, and Jackson’s candidacy challenged it by existing seriously in public life. The campaigns did not erase racial barriers, but they made them visible—and therefore contestable.

Second, Jackson’s campaign language became a template. His “Rainbow Coalition” speech at the Democratic National Convention articulated a party vision built on inclusion and solidarity, arguing that the Democratic coalition should not merely tolerate difference but treat it as its strength. In a country where political rhetoric often seeks to flatten difference into patriotic sameness, Jackson made difference sound like a mandate.

Third, the campaigns institutionalized voter engagement. They brought new voters into the process, created networks of activists and operatives, and normalized the idea that moral issues—poverty, racism, war—belonged in presidential debate, not only in protest signs.

Even opponents who dismissed Jackson as a “gadfly” had to respond to the constituencies he activated. His runs restructured attention. In politics, attention is often the first form of power.

The diplomat without a portfolio: Hostage releases and global visibility

Jackson also cultivated a role that infuriated some officials and thrilled many supporters: the unofficial envoy.

In the 1980s and early 1990s, Jackson traveled abroad to negotiate the release of Americans held by foreign governments. Accounts of these episodes emphasize both his audacity and his effectiveness. Biographical summaries describe his role in securing the release of a U.S. pilot held in Syria in 1983, negotiating releases from Cuba in 1984, and pleading for the release of foreign nationals held in Iraq on the eve of the Gulf War in 1991.

To admirers, these missions demonstrated a distinct kind of American power: moral credibility and personal persuasion, deployed outside official channels. To critics—particularly within administrations that wanted a monopoly on foreign policy—they looked like freelancing that risked undermining diplomacy.

But Jackson’s foreign interventions also reflected a domestic reality: many Americans, especially Black Americans, recognized that official channels often moved only under pressure, and that visibility could force action. Jackson had built his career on forcing institutions to respond. Internationally, he tried the same method.

He became, in effect, a man who believed that if a government could not or would not act, a citizen with enough stature might.

A movement figure who wanted governing power

If one thread runs through Jackson’s life, it is the insistence that economics is not neutral.

Operation PUSH’s mission centered on employment and business opportunities; Rainbow PUSH described itself as a human and civil rights organization that empowered people through grassroots advocacy and connections between the community and the disenfranchised. That language can sound generic until you see how Jackson used it: direct engagement with corporate leadership, public campaigns, boycotts, and negotiated commitments.

This part of his legacy is sometimes caricatured as “shake-down politics” by detractors. Yet it also anticipated what many institutions now treat as standard: diversity commitments, supplier diversity programs, and public reporting on representation. Ebony, for example, covered Jackson’s push for diversity in Silicon Valley, highlighting his engagement with tech leaders and the persistent underrepresentation of Black workers. These initiatives did not begin with Jackson, and they did not become mainstream solely because of him. But he forced the issue into spaces that preferred to treat themselves as meritocracies above social conflict.

Jackson’s approach asked a blunt question: if a company profits from a community, what does it owe that community? Jobs? Contracts? Respect? Presence at decision-making tables? In a capitalist democracy, those questions are political, not merely economic.

They were also uncomfortable. Jackson’s comfort with discomfort—his willingness to create friction to extract concessions—was central to both his effectiveness and his notoriety.

Controversy as a feature, not a bug

No honest account of Jesse Jackson can avoid the episodes that damaged trust, strained alliances, or revealed prejudice within the very coalitions he sought.

The most infamous was the 1984 remark in which Jackson used a slur against Jews and referred to New York as “Hymietown,” comments that became public through reporting and reverberated nationally. The controversy reopened fragile tensions between Black and Jewish communities—tensions shaped by divergent experiences, urban politics, and contested narratives of power and vulnerability. Jackson apologized, but the incident became a permanent footnote to his public image, frequently cited by critics as evidence of opportunism or underlying bias.

The episode matters not because public figures should be trapped forever by their worst words, but because coalition politics depends on trust. Jackson asked disparate communities to see one another as allies; language like that, even once, made the work harder.

His relationship to other polarizing figures of the era also complicated his legacy. Jackson’s critics argued that he sometimes tolerated or courted extremists for political benefit; supporters argued that coalition-building in America often requires engagement across uncomfortable lines, and that Jackson’s core agenda remained inclusive. The truth is that Jackson lived in the messy middle ground where moral leadership meets practical politics, and where purity tests can destroy alliances even as compromises can corrode integrity.

These controversies do not cancel his achievements. But they are part of the record, and they shape why Jackson remains, even in death, a complicated symbol.

A movement figure who wanted governing power

Many civil-rights leaders choose a posture of external critique: speak truth, mobilize people, pressure government, avoid the compromises of candidacy. Jackson did not.

He sought the power to effect change—not merely proximity to power—and believed that running for office was a form of movement work. That choice made him vulnerable to criticism that he sought fame. It also made him historically consequential, because it forced a question: what happens when a movement leader tries to become a national executive, not merely an advisor?

Jackson’s campaigns pressured the Democratic Party to address constituencies it often treated as turnout machinery rather than agenda-setters. They also made visible the party’s internal hierarchy: who was treated as serious, whose issues were “special interests,” whose anger was “divisive,” whose patriotism was assumed.

That struggle—between inclusion as rhetoric and inclusion as power—is still the central drama of American liberal politics. Jackson did not invent it. He staged it.

Reparations and the long memory of injustice

In later years, Jackson remained a voice on issues that the mainstream political class treated as too volatile. One of these was reparations for slavery. The Atlantic, in a 2019 interview, described Jackson as having made reparations a core issue in his presidential campaigns decades earlier, and revisited his view as Congress debated proposals to study reparations.

This is another example of Jackson’s tendency to push questions forward before the country was ready to answer them. Critics saw this as grandstanding; supporters saw it as agenda-setting. Either way, the pattern is consistent: Jackson treated the American present as accountable to the American past, and treated racial justice as inseparable from material repair.

In that sense, his politics were less about momentary outrage and more about historical continuity: what the country owes, what it has taken, what it refuses to name.

Decline, illness, and the public life of aging leaders

In 2017, Jackson disclosed that he had been receiving outpatient care for Parkinson’s disease for two years, a diagnosis he shared publicly in a letter to supporters. In late 2025, reporting indicated he had been hospitalized for progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP), a rare neurological disorder often confused with Parkinson’s early on. The Root reported on his family’s statement disputing inaccurate reports and clarifying that he was stable and breathing without assistance while managing PSP.

Illness does not rewrite a life, but it changes how a public figure inhabits the world. For movement leaders, aging raises questions institutions often avoid: succession, accountability, the difference between symbolic leadership and operational control. Jackson’s long tenure as an emblem of civil rights sometimes blurred these lines. The charisma that built organizations can also delay transitions, because supporters fear what comes after the founder.

Yet the existence of Rainbow PUSH as a continuing institution—described as an international human and civil rights organization founded by Jackson—suggests that he did build something that could outlast him. Whether it thrives in his absence is a question of leadership and relevance, but endurance itself is a form of achievement.

How to measure Jesse Jackson

If you measure Jesse Jackson purely by elections, he lost the presidency twice. If you measure him purely by moral purity, he faltered publicly in ways that wounded allies and gave ammunition to opponents. If you measure him purely by institutional outcomes, you can point to organizations, voter registration, corporate commitments, and a shift in party rhetoric.

But Jackson’s real impact is best measured by a different metric: the range of the possible.

Before Jackson, the idea of a Black candidate mounting a serious national campaign for president belonged to the margins of imagination. After Jackson, it belonged to history—and therefore to precedent. That precedent mattered when later candidates—Barack Obama most famously—navigated the terrain Jackson helped reveal. Jackson’s campaigns demonstrated that a constituency could be built around a candidacy that centered civil rights, poverty, and inclusion, even if the broader electorate and party elites resisted.

His Rainbow Coalition concept also anticipated the demographic and cultural shifts that now define American politics. The idea that political power could be assembled from the “excluded” is now common language, though often practiced unevenly and sometimes cynically. Jackson preached it as a moral necessity and pursued it as a strategy.

And then there is the question of voice. Jackson’s rhetorical power—the capacity to fuse sermon and stump speech—helped define a style of public leadership that speaks simultaneously to conscience and calculation. He could sound like prophecy and like a negotiator in the same breath. That duality is part of why he was so often on television: he made conflict legible, and he made hope sound like a demand.

In a nation that frequently celebrates civil-rights heroes in the abstract while resisting the policies they fought for, Jesse Jackson forced the country to face the concrete. Jobs. Wages. Representation. War. Reparations. Voting. He was not content with commemorations. He wanted results.

That insistence made him indispensable and exhausting, heroic and controversial, larger than life and stubbornly human.

The legacy, after the slogans

When Jackson died, the familiar lines returned—icon, leader, trailblazer—because America needs a way to close the book on complicated figures. But Jesse Jackson’s story does not resolve so cleanly. The questions he raised remain open: How does a democracy repair historical theft? What does economic justice require? Can a coalition of the marginalized govern without reproducing the exclusions it condemns? What does it cost to turn moral movements into political machines? And what happens when the face of a movement becomes as famous as its agenda?

If you want to honor Jackson without sentimentalizing him, you don’t start by repeating his slogans. You start by noticing what the slogans were trying to accomplish. “Keep hope alive” was never meant to be decorative. It was a command to outlast cynicism, to organize anyway, to build coalitions where the American culture preferred divisions, to push institutions that move only when pushed.

Jackson spent his life pushing.

Whether the country keeps moving is not only a question of what he did. It is a question of what those who inherit his unfinished work are willing to do next.

More great stories

Truth, Spoken and Rewritten