Hickman’s pictures are not merely documentary. They are counter-archives—evidence assembled against erasure.

Hickman’s pictures are not merely documentary. They are counter-archives—evidence assembled against erasure.

By KOLUMN Magazine

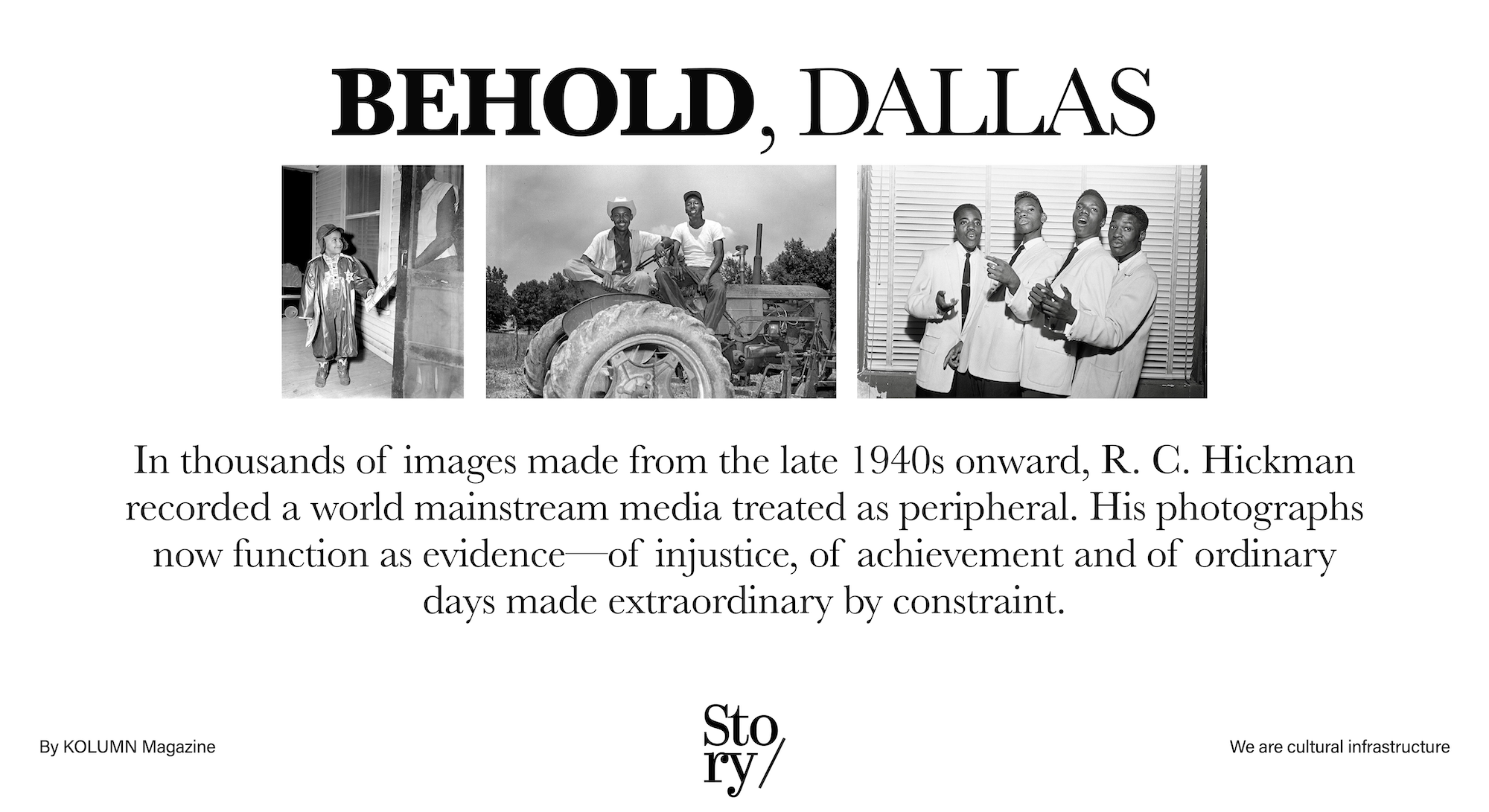

There are photographers whose names become shorthand for an era, and there are photographers whose images become the era’s operating system—quietly explaining how power moved, where it stopped, and what people did inside the boundaries drawn around them. R. C. Hickman belongs to the second category. He did not need a national bureau or a glossy masthead to make history visible. He needed proximity: to Black Dallas, to its institutions and rituals, to its joy and its vulnerabilities, and to the everyday humiliations that segregation tried to normalize. When historians and curators describe him as the “unofficial photographer” of the African American community in Dallas during the 1950s, they are not reaching for a poetic epithet. They are naming a civic function his work performed in real time—and continues to perform now.

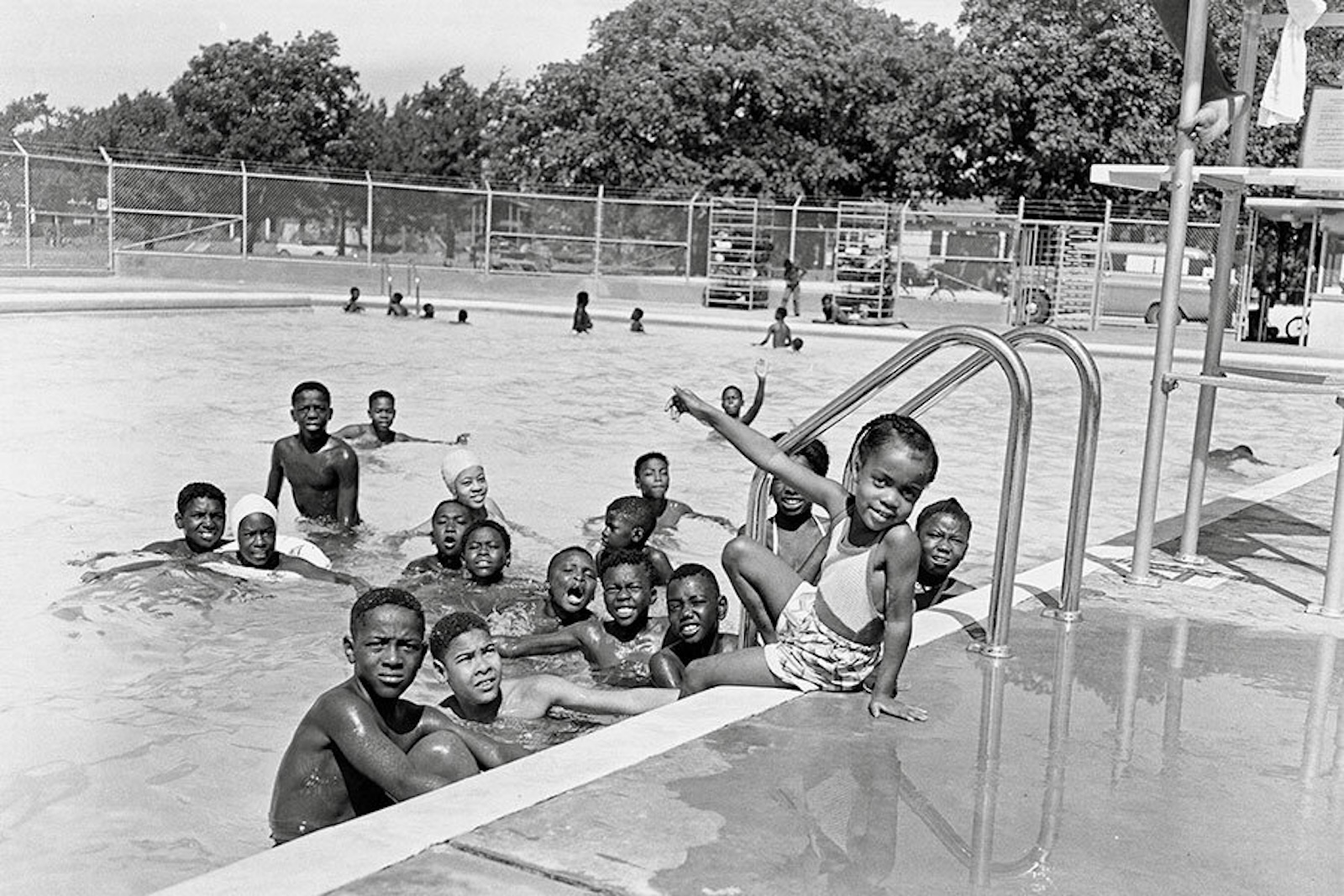

Hickman’s significance is easiest to feel when you stop treating civil rights photography as a genre limited to marches, arrests and fire hoses. His archive holds those moments, and some of them carry the unmistakable charge of danger. But it also contains what movements are made of: meetings, planning, sermons, schoolrooms, social clubs, crowds gathered for entertainment, families dressing for church, teenagers and elders claiming public space with their bodies. That breadth matters, because it reframes the mid-century Black freedom struggle not as a sequence of national “events,” but as a continuum of community life under pressure—life that still insisted on dignity, style, ambition and celebration. Curators have repeatedly emphasized this idea: Hickman photographed a community “largely invisible to white Americans,” one that was simultaneously part of mainstream America by accomplishment and lifestyle and yet excluded by race.

In that framing, Hickman’s pictures are not merely documentary. They are counter-archives—evidence assembled against erasure. They explain how Dallas worked on the “Black side,” to use Hickman’s own phrase as recorded by the Texas State Historical Association’s Handbook of Texas. And they reveal the mechanisms of inequality with a specificity that general histories often soften: the physical conditions of segregated schools; the choreography of protests and boycotts; the presence of signs and spaces that policed who could enter, sit, wait, be served.

Becoming R. C. Hickman: East Texas origins, Dallas adolescence, and an Army-trained eye

Hickman was born Rufus Cornelius Hickman in Mineola, Texas, in 1922, and his family moved to Dallas during the Great Depression—an early relocation shaped by work, survival and the gravitational pull of a city that promised more than rural East Texas could.

The outline of this biography can sound familiar—small-town birth, big-city move, wartime service, return home—but the details are where Hickman’s later practice begins to come into focus. The Briscoe Center’s memorial notice and the Handbook of Texas both underscore how early he learned the hustle and logistics of the printed word’s economy: selling papers, circulating publications, understanding that communities are stitched together by information and by who controls its distribution.

He attended Tillotson College in Austin (now part of Huston–Tillotson University) before the Army redirected his life.

World War II was not only an interruption; it was a technical education. Hickman’s interest in photography developed through military service, where he earned credentials as an official Army photographer. The Army did not invent his eye, but it disciplined it—teaching him how to work under constraints, how to handle equipment, how to produce usable images on assignment. It is hard not to see the through-line between that training and the later scenes in Texas where speed, judgment and composure mattered: a picket line that could turn hostile, a courthouse where an image might become evidence, a desegregation flashpoint where the photographer himself was at risk.

One complication appears even in the institutional record: some exhibition materials list Hickman’s birth year differently than the 1922 given by the Briscoe Center’s memorial and the Handbook of Texas. The Briscoe Center’s exhibit description has used a different date in at least one instance, a reminder that archives—while essential—are also human systems subject to error, revision and contested documentation. The weight of the evidence from the Briscoe Center’s obituary notice and the TSHA biography supports 1922.

The Dallas Star Post and the ecosystem of Black print culture

After the war, Hickman returned to Dallas and began a professional career at the Dallas Star Post, an African American–owned newspaper where he worked not only as a photographer but also in sales and circulation—roles that placed him inside the machinery of Black civic communication in a segregated city.

To understand why that matters, it helps to remember what local Black newspapers were in mid-century America. They were not merely news outlets. They were community bulletin boards, advocacy platforms, reputational engines, and informal public records. When mainstream dailies ignored Black neighborhoods except as sites of crime or “disturbance,” Black-owned and Black-serving papers documented achievement, grief, worship, conflict and celebration in ways that allowed a community to see itself whole. Hickman’s career sits inside that tradition. The Handbook of Texas notes that he “captured Dallas ‘on the Black side’” and photographed what major media ignored across the 1940s through the 1970s.

He also worked for other outlets, including the Dallas Express, and contributed to regional Black press networks. The University of North Texas Libraries’ “Black Living Legends” exhibit places him in a professional constellation that included major Black newspapers and national publications, naming the Kansas City Call alongside the Dallas Star Post and magazines such as Jet and Ebony.

The effect of this kind of work is cumulative. You become the person who is called when something is happening, and you become the person who knows how to be present without being an intrusion. You learn how to move in sanctuaries and meeting halls, how to work quickly at nightclubs, how to make portraits that convey status without parody. You learn what a community wants to remember—and what it needs preserved even when it would rather forget. Hickman’s archive, as described by the Briscoe Center, spans Dallas news events, nightclubs and entertainers, schools and universities, funerals, and “notable Dallas citizens,” with the majority created during the 1950s.

Working for the NAACP: Photographs as documentation, proof, and courtroom testimony

If the Star Post gave Hickman a platform, the NAACP gave him a mandate. The Handbook of Texas states that he became the official photographer for the local NAACP, recording scenes to be used in desegregation cases and sometimes being called to court to testify about his pictures. That is a different kind of photography from cultural coverage, and it demanded a different sort of rigor. You are no longer simply making images for publication; you are producing documentation that may be contested by hostile institutions.

The Briscoe Center’s memorial notice is explicit on this point: Hickman’s NAACP photography documented inequities in Dallas school conditions and exposed him to dangerous situations during the fight to end segregation. The archive itself includes photographs made specifically for NAACP court cases, reinforcing that these images were meant to function as evidence.

Evidence photography has its own ethics. The photographer must be accurate about what is shown, careful about context, and mindful that an image can be both truth-telling and vulnerable to misinterpretation. Hickman’s work, at least as described in institutional summaries, leaned into specificity. The Handbook of Texas describes his photographs of African American schools depicting “overturned desks, littered floors, and broken windows,” details that make inequality visible without requiring rhetorical flourish.

This is a form of visual journalism that collapses the distance between reporting and advocacy, but not necessarily between reporting and accuracy. The NAACP’s use of photography in desegregation fights depended on factual grounding. Hickman’s role, then, was to make the case legible. In a state where “separate but equal” persisted as a legal fiction long after it had become a moral farce, the camera helped demonstrate that “equal” was a lie told in official language.

Mansfield, 1956: The assignment that turned into a chase

The episode most often invoked to illustrate Hickman’s courage is the Mansfield school desegregation crisis. It is a story about a photographer, yes—but it is also a story about how white resistance to integration treated documentation itself as a threat.

On August 30, 1956, Hickman arrived in Mansfield, Texas, on assignment for the NAACP to cover the attempted integration of the local high school. According to a University of Texas at Austin news feature on civil rights photography, he approached the school and saw effigies of Black students—mock lynchings—swinging from the trees. He worked quickly to photograph the scene, was spotted, and was chased by a mob. He escaped to his car, but the pursuit continued toward Fort Worth until he fled into a funeral home, where the chase stopped.

The Handbook of Texas corroborates the essentials: Hickman traveled to Mansfield to photograph a mock lynching, was seen by participants, and was chased from Mansfield to Fort Worth, escaping by “ducking into a friend’s funeral home parking lot and closing the gate.”

Mansfield’s historical record shows how fevered and theatrical the resistance was. A digital exhibit on the crisis describes crowds of hundreds gathering at the school, effigies displayed as protest, and the involvement of Texas Rangers dispatched by Gov. Allan Shivers. It includes details of intimidation that hover between menace and spectacle—like a photograph described in which a protester held a baby alligator as a warning that Black people would be “gator bait.”

If Hickman’s chase reads like a set piece from a film, it is because it carries the elements of American racial violence in miniature: the spectacle of threat, the collective nature of intimidation, the attempt to control what can be seen, and the implicit understanding that a photograph can outlive a crowd. The fact that Hickman came to Mansfield as a Black photographer documenting white terror added another layer of risk. The mob did not merely object to integration; it objected to the evidence of its own behavior.

That is why Mansfield matters to Hickman’s legacy beyond the adrenaline of the chase. It shows the premise of his work: that visibility was a battleground, and that the ability to document could itself be an act of defiance.

The everyday archive: Churches, schools, nightclubs, and the full geography of Black Dallas

A risk-focused narrative can distort a photographer’s life by implying that significance only appears at moments of open conflict. Hickman’s deepest contribution is arguably the opposite: the patient, sustained documentation of Black Dallas as a lived world.

The exhibition materials for Behold the People: R. C. Hickman’s Photographs of Black Dallas, 1949–1961 describe images that reveal how individuals “survive, grow, and understand themselves” within a broader community context. That phrasing resists the trap of reducing Black life to suffering. It emphasizes structure—how people built meaning inside constraint—and it suggests why Hickman’s archive remains so useful to scholars and curators.

The Briscoe Center’s memorial note lists the subject matter bluntly, almost like a map legend: Dallas news events; entertainers and nightclubs; schools and universities; funerals; notable citizens. It is the kind of list that, on first reading, can feel generic—until you realize it is describing the interior life of a segregated metropolis. These were not merely “topics.” They were the arenas where Black Dallas constituted itself as a public.

Churches, for example, functioned as spiritual homes and political headquarters. Schools were sites of aspiration and, in segregated facilities, of state-sanctioned neglect. Nightclubs and performance venues were both leisure and livelihood—spaces where Black artistry and Black audiences met on their own terms, even as Jim Crow tried to hem them in. Funerals were not only private grief; they were public accounting, moments when a community acknowledged who it had lost and what it had endured.

Hickman’s images did not have to shout for this to be legible. A photograph of a “Colored waiting room” in 1952, circulated in exhibition materials, places segregation into the built environment—an architectural cruelty rendered ordinary by signage.

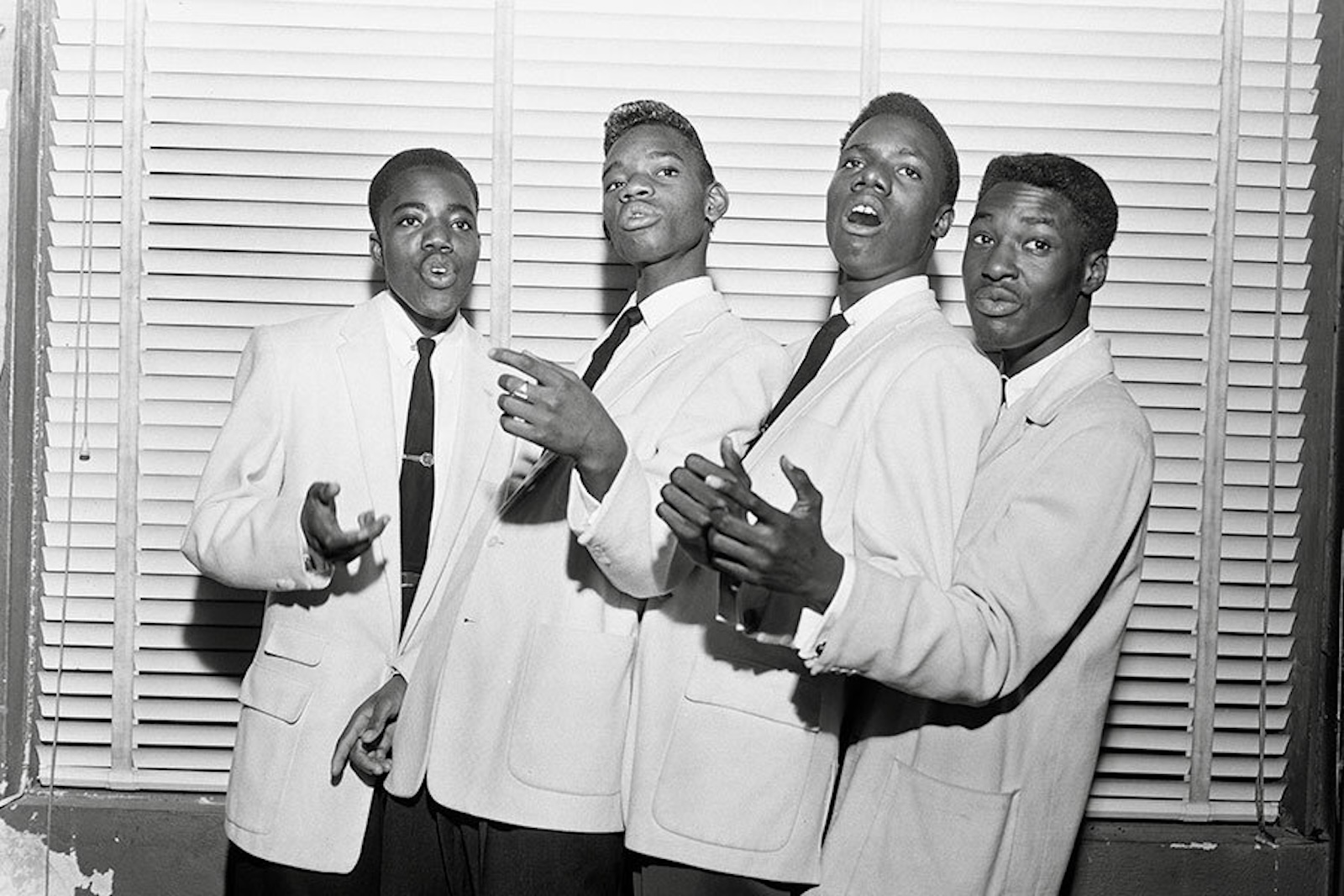

At the same time, the exhibit points to portraits of musicians and entertainers—figures such as Nat King Cole photographed by Hickman in 1954—suggesting how Black Dallas intersected with national Black fame, and how those encounters became part of local memory.

This is one reason Hickman’s work resists being filed neatly under “civil rights photography.” He photographed civil rights activity, but he also photographed the society that made civil rights necessary, and the community that persisted while fighting it.

Photographs of protest: The Texas State Fair boycott and the choreography of collective action

One of the clearest examples of Hickman’s value as a local witness appears in a Bullock Texas State History Museum artifact essay about NAACP Youth Council picketing the Texas State Fair in 1955. The essay situates the protest within the fair’s segregated history—“Colored People’s Day,” later “Negro Achievement Day,” and rules that allowed Black attendance but restricted participation. It describes Juanita Craft’s leadership and the Youth Council’s strategy: picketing a parade, encouraging boycotts, refusing to enter the fair.

In the middle of that historical explanation is a line that re-centers Hickman: “The boycott, and the majority of other civil rights activity in Dallas, was captured on film by photographer R. C. Hickman.” The phrase is telling. It implies not a one-off appearance but a sustained presence—Hickman as the person who repeatedly showed up to make public records of what would otherwise vanish into rumor and oral memory alone..

The essay also reprises the biographical arc—Mineola birth, move to Dallas in the 1930s, Tillotson College, Army photographer, work for the Dallas Star Post—and describes him again as the “unofficial photographer” of the African American community in the 1950s, noting his documentation of pivotal civil rights moments, including visits by Martin Luther King Jr. and Thurgood Marshall.

What is striking about this story is that it highlights civil rights as organization rather than only confrontation. Teenagers with signs. A planned refusal. A boycott that tried to make segregation expensive—socially, politically, publicly. Hickman’s camera, in this context, is part of the protest’s infrastructure. It extends the demonstration beyond the street into history.

Famous faces and local worlds: King, Marshall, Fitzgerald—and why those images matter

Hickman photographed an array of prominent figures who passed through Dallas. The Briscoe Center’s memorial notice lists Martin Luther King Jr., Thurgood Marshall, Ella Fitzgerald, and Joe Louis among the “renowned figures” he photographed during their visits. The Handbook of Texas adds Eleanor Roosevelt as well, emphasizing that his archive included “famous faces” of multiple races who visited the city.

It is tempting to treat these portraits as celebrity adjacency, but their deeper meaning is local. A photograph of a national figure in Dallas becomes evidence of Black Dallas’ connectedness—its place within wider circuits of politics, entertainment and movement-building. It also speaks to the importance of venues like churches and auditoriums where such figures could appear to Black audiences even when white-controlled institutions restricted access.

Those images also complicate a simplistic narrative of the South as culturally isolated. Black performers toured. Black legal strategies traveled. The movement’s leaders moved between cities. Hickman’s photographs record those intersections from the perspective of the community that hosted them.

The Humanities Texas exhibition page includes an epigraph attributed to Hickman about the limited seating Black patrons were permitted at certain theaters—a memory of being allowed only a few seats high in the balcony, the “buzzard roost.” This kind of first-person testimony, placed alongside images, gives the archive voice as well as sight. It reminds viewers that Hickman was not only a witness but also a participant in the segregated world he photographed.

Donating the archive: From working negatives to public history

In 1985, Hickman donated his photographic archive to what is now the Dolph Briscoe Center for American History at the University of Texas at Austin. This act is central to his long-term impact, because it moved his work from private custody and local circulation into a research infrastructure designed for preservation and access.

The Briscoe Center describes the R. C. Hickman Photographic Archive as consisting primarily of 4-by-5-inch negatives created during his professional career, including work for the Dallas Star Post and the Dallas Express, along with freelance assignments and photographs documenting school segregation for NAACP court cases. Even at the level of format, those details matter: large-format negatives preserve an extraordinary amount of information—faces in the crowd, signage on a wall, the condition of a room—details historians can return to decades later.

In 1994, the center published a book drawn from this archive: Behold the People: R. C. Hickman’s Photographs of Black Dallas, 1949–1961. Institutional pages about the Briscoe Center’s photography holdings and the book itself emphasize that it reproduces over one hundred photographs and positions Hickman’s work as an exceptional visual record of Dallas’ Black community in the decades after World War II.

Exhibitions extended the work’s reach. A Briscoe Center exhibition description notes that the center showcased Hickman’s photographs to commemorate his centenary and the 25th anniversary of the book, and that a companion exhibit was displayed at Dallas City Hall. Meanwhile, Humanities Texas has circulated a traveling exhibition version consisting of framed photographs and narrative panels, supported in part by a National Endowment for the Humanities “We the People” grant—an institutional signal of the work’s civic and educational value.

The story here is not only about honor. It is about how archives shift power. When a body of work is preserved, cataloged and exhibited, it becomes harder for a city—or a nation—to pretend it does not know what happened.

Mentorship, retirement, and a legacy that kept circulating

Hickman retired from professional photography in the 1970s, and later shared his experience through lectures and workshops in Dallas schools, according to the University of North Texas Libraries exhibit and institutional summaries. That detail matters because it extends his influence beyond the archive. He did not only document Black Dallas; he helped train the next set of eyes that might document what came after.

The Briscoe Center’s memorial notice describes him as generous with his time, particularly when mentoring young students who came to talk about photography. That form of generosity can be overlooked in legacy narratives, but it is part of how cultural memory is sustained: not only through artifacts but through instruction, encouragement, and the passing down of craft.

Hickman died on December 1, 2007, in Dallas. His funeral was held at St. John Missionary Baptist Church, according to the Handbook of Texas, and he left behind a body of work that continues to circulate in exhibits, museum artifacts, university collections and public history projects.

Why Hickman matters now: Not nostalgia, but infrastructure for truth

The enduring temptation with mid-century photography is to treat it as nostalgia: beautiful black-and-white images, an aesthetic of the past. Hickman’s work resists that treatment because it is not simply “of” the past; it is about systems whose afterlives persist. Segregation’s signage may be gone, but patterns of exclusion remain legible in schools, housing, policing and public space. The UT Austin feature on civil rights photographers notes that these images “remain so salient,” capable of conjuring questions about the America we live in today as well as the one we inherited.

Hickman also matters because his archive demonstrates how local documentation can correct national narratives. Civil rights history is often told through a handful of cities and a roster of headline events. Dallas is not always centered in that story, and neither is Texas beyond a few familiar flashpoints. Hickman’s pictures insist on Dallas’ centrality to its own freedom struggle—and on Texas’ place within the national conflict over integration and citizenship. His Mansfield images connect a small town’s resistance to a wider pattern of intimidation, and they do so with a specificity that prevents abstraction.

Perhaps most importantly, Hickman’s work expands what counts as historic. In his images, history does not only happen when a governor sends Rangers or a mob gathers at a school. History also happens at a theater where only a few seats are available to Black patrons, at a fair where participation is restricted by policy, at a community meeting where strategy is discussed, and at the funerals where people bury the cost of living inside an unequal city.

That is why Behold the People is not just a title. It is a directive. Look closely. Look beyond the official story. Look at the people who were there, making a life, making a record, making an argument simply by refusing to disappear.

More great stories

Truth, Spoken and Rewritten