In the end, this is what Oklahoma is deciding: whether to keep a reconciliation program that can function without descendants, or to insist—plainly, in statute—that those most directly linked to Greenwood’s destruction are not a factor the state may consider, but the people it shall serve first.

In the end, this is what Oklahoma is deciding: whether to keep a reconciliation program that can function without descendants, or to insist—plainly, in statute—that those most directly linked to Greenwood’s destruction are not a factor the state may consider, but the people it shall serve first.

By KOLUMN Magazine

In Oklahoma, where legislative language often carries the weight of history, the Tulsa Reconciliation Education and Scholarship Program—TRESP—has become a case study in how a state can acknowledge an atrocity while withholding the tools that would meaningfully address it.

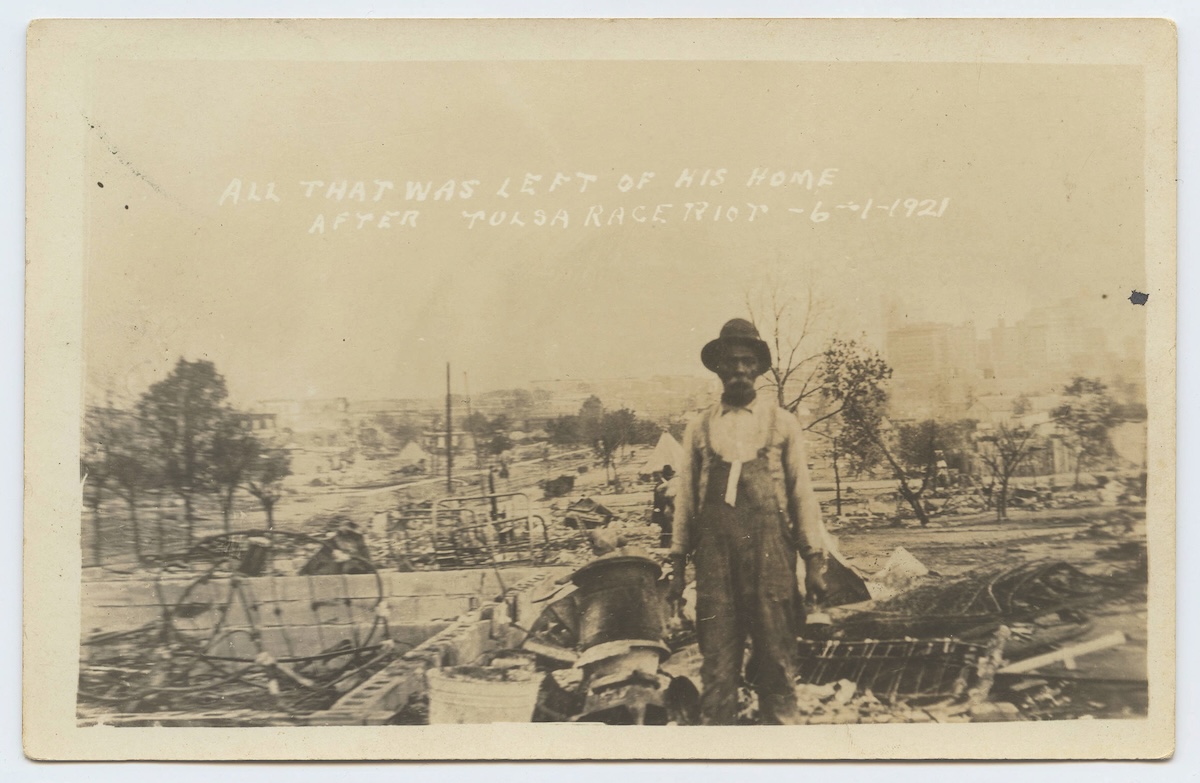

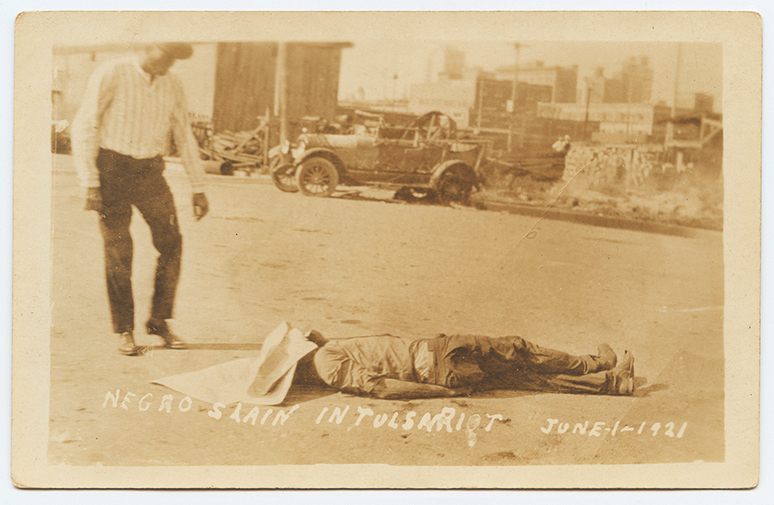

The scholarship exists because Oklahomans could no longer plausibly pretend that the destruction of Greenwood in 1921 was a footnote. For decades, survivors, descendants, and their allies petitioned the state to take responsibility for what happened in Tulsa: the looting and burning of a thriving Black district; the displacement of families; the suppression of claims; the public amnesia that followed. By the late 1990s, pressure had become institutional. In 1997, State Rep. Don Ross and Sen. Maxine Horner authored House Joint Resolution 1035, a measure that, in its early form, contemplated reparations before political compromise redirected it toward the creation of a state commission.

That commission—the Oklahoma Commission to Study the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921—did what official bodies sometimes do when forced into the open: it built a record, identified survivors and descendants, and recommended concrete forms of restitution. In a preliminary report embedded in its final documentation, the commission set out “suggested forms of restitution in priority order,” including direct payments to survivors, direct payments to descendants, and, third on the list, “a scholarship fund available to students affected by the Tulsa Race Riot.”

But the commission’s recommendations collided with Oklahoma’s governing reality: a Legislature dominated, then and now, by competing priorities—tax policy, broad education funding fights, the politics of “race-neutrality,” and a reflexive resistance to anything framed as reparations. The state’s chosen response was narrower than the moral indictment the commission laid out. The “1921 Tulsa Race Riot Reconciliation Act of 2001” created TRESP, and, in 2002, lawmakers passed HB 2238 to amend and clarify the scholarship’s statutory framework.

TRESP became Oklahoma’s most tangible statewide program linked to the massacre’s legacy. Yet from the start, it also became something else: a politically survivable substitute for the commission’s more direct demands. Human Rights Watch, in a blunt assessment released around the massacre centennial, argued that the scholarship program—while symbolically significant—was not designed to guarantee Black beneficiaries, descendant beneficiaries, or even applicants with a demonstrated connection to Greenwood’s victims.

Over the last several years, a small group of Democratic lawmakers from Tulsa—most prominently Rep. Regina Goodwin, and before her, leaders including Don Ross and Sen. Kevin Matthews—have tried to close the distance between what the state said in 2001 and what it has actually done since. Their efforts have tended to come in incremental steps: a bill that expands eligibility here, an appropriation that increases funding there, a clause that strengthens descendant preference in one session—followed by stall tactics, conference deaths, or rewrites that drain the most reparative elements out of the text.

What makes TRESP politically revealing is not simply that it has shortcomings—most programs do—but that its shortcomings align neatly with the Legislature’s unresolved discomfort with the underlying premise of the scholarship: that Greenwood was destroyed through tolerated, and often facilitated, public failure, and that public responsibility should be tangible.

A scholarship can be tangible. But only if it is built to reach the people it is supposed to repair.

From a commission’s truth to a Legislature’s compromise

The commission’s final report, compiled by historian Danney Goble, carefully documented the state’s mandate and the commission’s work—identifying survivors, preserving evidence, and speaking plainly about collective responsibility. The report’s embedded restitution recommendations were direct enough to be politically dangerous: cash payments to survivors and descendants, along with investments like an enterprise zone and memorialization, were all listed in priority order. The scholarship recommendation, crucially, was not framed as charity. It was framed as restitution—part of a “real and tangible” repair of “emotional as well as physical scars.”

In the years that followed, however, the scholarship became the easiest piece of restitution to institutionalize without conceding the principle of reparations. A program routed through higher education administrators and funded subject to appropriations could be presented as opportunity rather than accountability. That political reframing—opportunity instead of repair—explains much of what came next.

State Regents documentation and higher-ed agenda materials describe the scholarship’s origin in the 2001 act and the 2002 statutory amendments, including HB 2238. A 2002 Oklahoma Senate legislative summary likewise notes HB 2238 (Ross/Horner) as a measure that modified and clarified provisions related to the Tulsa Reconciliation Education and Scholarship Act and created a mechanism for taxpayer donations to the trust fund.

That history matters because TRESP is often discussed as if it were a settled artifact of reconciliation—an old program that simply needs minor tuning. In reality, it has always been contested: in how it defines eligibility, in how it is funded, and in whether it is allowed to behave like restitution rather than a generic scholarship.

What TRESP is supposed to do—and what it actually does

In its current structure, TRESP sits under the Oklahoma State Regents for Higher Education, with awards tied to tuition equivalencies and administered through processes that, at least on paper, can serve up to 300 scholarships annually. The program has been promoted through higher-ed portals that emphasize its purpose as preserving awareness of the 1921 massacre and encouraging applicants with evidence of direct lineal descendancy to apply.

Eligibility standards, as presented on state scholarship information pages, have historically included a taxable family income ceiling (long stated at $70,000), Tulsa Public Schools attendance or related poverty-linked geographic criteria, and residency within the Tulsa School District framework.

But those criteria reveal the program’s central tension: TRESP was conceived as a response to a racial atrocity and the destruction of a specific community, yet it was structured to rely heavily on socioeconomic proxies—poverty thresholds, free-and-reduced lunch rates, census block poverty rates—rather than explicit prioritization of descendants. Human Rights Watch noted that the scholarship as implemented contained “no requirement” that recipients be Black or descendants or otherwise connected to the massacre, which, from a reparations perspective, is not an incidental design choice but the point at which the state’s reconciliation stops short.

Funding has compounded the issue. Reporting in Oklahoma has described scholarship dollars as limited relative to the program’s statutory ambitions. In 2023, KOSU quoted a State Regents official describing funding as “a pittance,” and reported that over five years 60 students received a total of $75,500—numbers that underline how far reality can drift from the headline promise of “up to 300” awards.

That disconnect has been the backdrop for a multi-session reform push: if Oklahoma will not embrace direct reparations, then the least it can do—Tulsa Democrats argue—is make the scholarship program behave as if it were designed for the people it was created to address.

The Tulsa Democrats who kept pressing the state

Don Ross’s role is foundational. Long before TRESP existed, Ross—working alongside Sen. Maxine Horner—helped initiate the state process that produced the commission and its report. Tulsa Public Library historical material describes HJR 1035 and the way reparations language was stripped before the commission was created. The final report itself lists Rep. Donn Ross among sponsors connected to the commission’s work.

Kevin Matthews occupies a different position in the story. As a Tulsa legislator and later a prominent figure connected to centennial-era institutions, Matthews has frequently been cited in coverage of the ongoing reparations debate and the state’s failure to deliver comprehensive justice. Human Rights Watch referenced then-Sen. Kevin Matthews in its critique of Oklahoma’s limited follow-through, placing the scholarship program within a broader argument about unresolved accountability.

Regina Goodwin, now in the Senate, has been the most persistent legislative architect of recent TRESP reforms. Her efforts have combined public argument with the slow mechanics of lawmaking: drafting, committee pushes, negotiation, and attempts to extract appropriations in a Legislature that often prefers to treat the massacre as a historical tragedy rather than an ongoing policy obligation. The incremental nature of her wins is itself a political fact: in a system where the dominant coalition does not want to concede the principle of reparations, reform tends to arrive as technical amendments rather than moral declarations.

That incrementalism is visible in the bill history.

The modern bill trail: Expansion attempts, conference deaths, and the fight over priority

In 2022, a reform bill (HB 4154) drew attention as an attempt to change how the scholarship operated, and local coverage framed it as an effort to better align the program with descendants and those impacted. In June 2022, Oklahoma lawmakers approved $1.5 million in new funding for the program, which Rep. Goodwin described as a start—an acknowledgement that the scholarship could not operate at scale without real appropriations.

Then came a larger push in 2025: SB 1054, sponsored by Sen. Goodwin, which would have updated eligibility and expanded reach. An Oklahoma Senate press release described the bill as modernizing a program created “nearly a quarter of a century” earlier and noted the long-stagnant income limit. The bill’s legislative path, however, ended in a familiar place—conference, then death—illustrating how even broadly popular reforms can be neutralized when they require the majority party to accept a clearer reparative logic.

By 2026, the conflict sharpened around two bills that, on the surface, appear similar—both raise income thresholds and address descendant-related criteria—but diverge sharply in what they require.

SB 2040: Turning descendants from an optional factor into first priority

SB 2040, introduced by Sen. Regina Goodwin, is explicit in its throughline: if descendants are part of the program’s moral rationale, they should not be treated as incidental.

The introduced text raises the family income ceiling to $125,000, and, importantly, creates “no family income limit” for applicants who are direct lineal descendants. It also expands eligibility beyond the Tulsa School District to qualified students in other public school districts in the United States who are direct lineal descendants, tying that expansion to the statute’s descendant definition.

Most significantly for the current fight, SB 2040 changes the priority framework. Instead of leaving descent to discretionary consideration, it states that the State Regents’ selection process “shall give first priority status” to an applicant who is a direct lineal descendant of a person who lived in Greenwood during the defined window and “was a victim of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre.”

The bill also moves toward a clearer verification architecture. It contemplates verification of documentation by “an organization or individual engaged in genealogy and research of descendants and history of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre and Greenwood Area,” and requires rules and application language that directly prompts descendant identification.

In other words, SB 2040 tries to solve the exact shortcomings you flagged: it elevates descendants from non-priority to priority, modernizes income caps (and removes them for descendants), and makes verification and the application process more explicit.

HB 3051: “May consider” and the politics of discretion

HB 3051, authored by newly elected Rep. Ronald Stewart (D-73), is the current flashpoint because it appears to modernize TRESP while leaving its most reparative element—descendant priority—fundamentally optional.

The introduced HB 3051 text raises the income threshold to $125,000. It modifies program language in multiple places, including replacing “resident” with “student,” shifting administrative provisions, and revising aspects of award computation.

But the critical clause appears in Section 2623(C): “The State Regents may consider as a factor, when determining the order of preference of applicants, whether an applicant is a direct lineal descendant…” The verb—“may”—does the work of political compromise. It preserves legislative deniability: the program can be described as descendant-aware, yet descendants remain dependent on administrative choice rather than statutory right.

HB 3051 also includes language stating that if descent is used as a preference factor, “it shall be applied to all applicants regardless of race,” a framing that echoes a long-standing legislative instinct to treat race-conscious repair as legally risky or politically untenable—even when the program is rooted in a race-based atrocity.

This is not merely semantic. The 2001 commission recommended restitution measures in a priority order that began with survivors and descendants—an unmistakable signal about who, in the commission’s view, was owed repair first. A scholarship that only “may” consider descendant status is, by design, structurally capable of reproducing the very outcome critics have condemned for years: a reconciliation program where direct connection to Greenwood is encouraged in brochures but not guaranteed in practice.

The Legislature’s competing priorities—and the quiet ways a promise gets narrowed

To understand why a single word can trigger such conflict, it helps to name the competing priorities that have hovered over TRESP since its creation.

One priority is fiscal: Oklahoma’s scholarship, on paper, can serve hundreds; in practice, its funding has often been too thin to meet the scale implied by statute. When appropriations are limited, discretion becomes power: administrators must decide who gets funded first, and lawmakers can avoid owning the ethical implications by delegating the hardest choices to agencies.

Another priority is ideological: for many legislators, “reconciliation” is palatable only if it is not “reparations.” That distinction shows up in a preference for race-neutral language, socioeconomic proxies, and optional rather than mandatory descendant prioritization. HRW’s critique of the scholarship’s design landed precisely here, arguing that the program did not require any connection to massacre victims.

A third priority is political risk management: making descendants first priority is a direct admission that the program is not merely a Tulsa poverty scholarship but a repair mechanism for a specific harmed population. SB 2040 embraces that admission; HB 3051 steps around it.

The result is the dynamic you asked the article to track: the state can point to TRESP as evidence of action while simultaneously structuring it so that its reparative intent is diluted at the moment of distribution.

The key shortcomings, in plain terms

Even without adopting any one political frame, the policy shortcomings are straightforward.

First, when descendant status is discretionary, descendants cannot rely on the program as a predictable form of redress. HB 3051’s “may consider” clause preserves that uncertainty. SB 2040’s “shall give first priority status” eliminates it.

Second, income thresholds must track economic reality or they become exclusionary over time. Goodwin’s bills and public statements have repeatedly pointed out that long-frozen income limits no longer reflect contemporary earnings. SB 2040 and HB 3051 both raise the threshold to $125,000, but SB 2040 goes further by removing the income limit for direct descendants.

Third, verification is not a minor administrative detail; it is the mechanism that determines whether “descendant” is meaningful or symbolic. SB 2040 pushes toward a defined verification approach tied to genealogy expertise and requires clearer application language and rules. HB 3051, while referencing documentation and attestation mechanics, does not resolve the central policy question of descendant priority because it leaves prioritization optional.

Why this fight matters now

It is tempting, in legislative reporting, to reduce the conflict to a personal or intra-party disagreement—Stewart versus Goodwin, House versus Senate, a freshman lawmaker’s learning curve versus a veteran’s insistence on precision. But the deeper story is institutional: Oklahoma has spent more than a century living with the consequences of Greenwood’s destruction and more than two decades living with the commission’s recommendations. It created TRESP as a substitute for the most direct forms of restitution, then constrained that substitute through design choices and funding levels that make it hard for the most clearly harmed population to consistently benefit.

That is why the current challenge—HB 3051’s “may consider” clause against SB 2040’s mandatory priority—reads as more than legislative drafting. It is a referendum on whether Oklahoma will continue to treat reconciliation as an aspirational label or as a statutory obligation with enforceable meaning.

The commission’s record is not ambiguous about intent. It placed direct payments to survivors first, direct payments to descendants second, and a scholarship fund third. That ordering was, at minimum, a moral roadmap. In a state where the first two steps were never implemented at scale, the scholarship became the remaining vehicle. Weakening it—by making descendant priority optional—pushes Oklahoma even farther from the logic its own commission advanced.

The argument the Legislature should confront

A fair-minded critic could say: a scholarship program should not discriminate; it should serve need; it should avoid creating a hierarchy of deservingness. But TRESP is not a general scholarship born from general need. It is a program created “because” a particular district was “greatly impacted both socially and economically” by a particular act of racial violence, as administrative code and statutory language make plain.

The question, then, is not whether the program should have standards. The question is whether Oklahoma will write those standards to match the reason TRESP exists at all.

SB 2040 does that by making descendant status first priority, modernizing income caps, and tightening verification. HB 3051 modernizes some parts of the program while leaving the core reparative question unresolved, precisely because “may” is a choice to preserve discretion where the commission’s intent points toward obligation.

If legislators want to claim reconciliation, they should support measures that strengthen TRESP rather than preserve loopholes. That does not require Oklahoma to resolve the entire reparations debate in one session. It requires the Legislature to stop treating a scholarship—its own chosen substitute for broader restitution—as if it were merely another line item to tweak without moral consequence.

In the end, this is what Oklahoma is deciding: whether to keep a reconciliation program that can function without descendants, or to insist—plainly, in statute—that those most directly linked to Greenwood’s destruction are not a factor the state may consider, but the people it shall serve first.

And in legislative language, as in history, the verbs matter.

More great stories

James Van Der Zee: The Photographer of Black Possibility