James Hemings cooked the early republic its most delicious illusions. He also, by the mere fact of surviving and insisting, helped expose them.

James Hemings cooked the early republic its most delicious illusions. He also, by the mere fact of surviving and insisting, helped expose them.

By KOLUMN Magazine

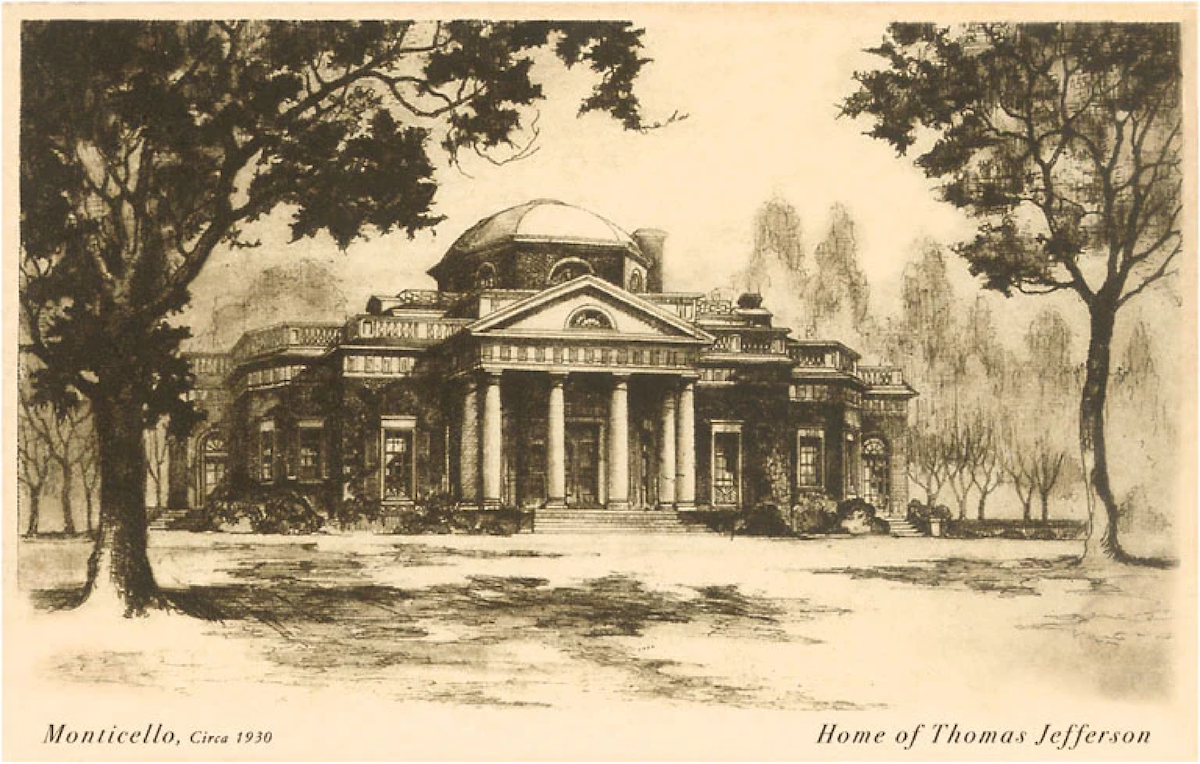

On a winter morning in Albemarle County, Virginia, the mountain air around Monticello can feel scrubbed clean—bright, cold, almost innocent. Tour groups move through Thomas Jefferson’s house with the practiced hush of a civic ritual. They admire the architecture, the gadgets, the books, the view that seems to flatten the landscape into a promise. And then, if they are lucky—and if the story is told with the fullness it deserves—the tour turns toward heat: the workrooms, the smells, the labor that made the elegance possible. Toward the kitchen.

For much of American memory, Jefferson’s “love of good food” has been treated as a charming footnote to genius. A gourmand Founding Father: imported wines, French sauces, ice cream, the famous “macaroni.” But the kitchen, like the country, runs on a harder truth. The culinary sophistication often credited to Jefferson’s personal taste was executed—conceptualized, practiced, refined—by human beings he legally owned.

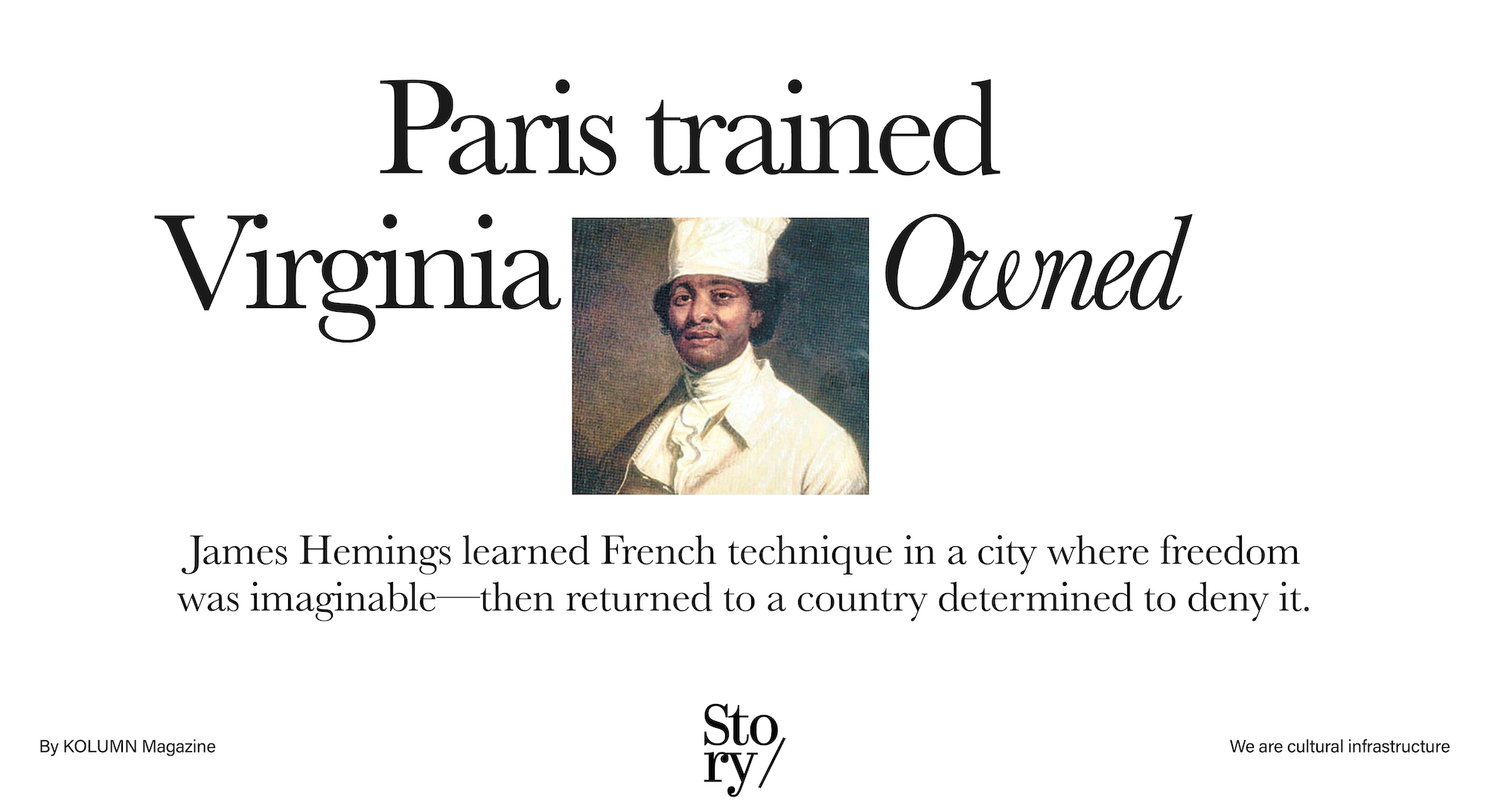

Among them was James Hemings, born in 1765 and dead by 1801, a man whose life reads like a parable about the early republic’s talent for moral compartmentalization. Hemings was enslaved, trained in France, and made head chef for Jefferson at the precise moment the United States was inventing itself as a public performance: dinners as diplomacy, taste as power, the domestic sphere as statecraft. He was also the brother of Sally Hemings and part of a large, complicated family network bound to Jefferson by blood, property, and coercion—one of the most famous family stories in America, and yet still widely misunderstood.

If you want to understand James Hemings, you have to look past the tidy headline of “the man who popularized mac and cheese” and treat him as something rarer in the historical record: an enslaved artisan whose mastery forced elites to bargain with him, whose mobility exposed him to ideas of freedom, and whose afterlife reveals how the country has laundered its pleasures through other people’s pain. Hemings is not just a culinary ancestor. He is an index of what America chose to credit, what it chose to forget, and what it is now being asked to remember.

The Hemingses: A Family Inside the House

James Hemings entered the world in colonial Virginia, in a system that rendered family ties both intensely meaningful and legally meaningless. He was born into the Hemings family, whose matriarch, Elizabeth (Betty) Hemings, had ten children and—through a web of forced relationships typical of slavery’s sexual economy—became bound to the estate of John Wayles, a planter and Jefferson’s father-in-law. When Wayles died, the Hemings family was inherited into the Jefferson household through Jefferson’s marriage to Martha Wayles Jefferson. In the cold arithmetic of property, that inheritance included James. In the warmer, more volatile arithmetic of blood, it also meant that James and Sally Hemings were linked to Jefferson’s family in ways that defy the neat categories Americans prefer: Jefferson’s wife was a half-sister to several Hemings children through Wayles.

The Hemingses were not a small domestic unit tucked away at the edge of Monticello; they were, over generations, a core workforce. They labored in skilled positions—cooking, brewing, tailoring—roles that could bring proximity to power and, sometimes, limited leverage. Peter Hemings, James’s younger brother, would later be trained as a cook and brewer. The family’s labor was a kind of internal infrastructure: it made Jefferson’s household run, and it made Jefferson look like Jefferson.

James Hemings is often described as “Paris-trained,” and the phrase can sound almost glamorous—until you remember the premise: Jefferson did not send him to France as a scholarship student. He brought him as property.

Paris and the Geometry of Freedom

In May 1784, Jefferson was preparing to go to France as a minister to the French court. He summoned James Hemings to accompany him, intending to have the young man trained in French cooking. It was an audacious project, one that reveals Jefferson’s priorities with unsettling clarity. Jefferson wanted French technique—its sauces, pastries, and presentation—to signal refinement in an American diplomat’s home. He wanted the soft power of the table. And he wanted it produced by a person he could control.

Hemings was about nineteen when he arrived in Paris. In the city’s kitchens, he apprenticed and studied; he learned not only how to cook but how to command a culinary system—how to coordinate purchases, manage timing, execute multiple dishes, and serve elite guests at Jefferson’s residence on the Champs-Élysées. The work was technical and exhausting, the kind of skill that is invisible only if you’ve never watched a kitchen run.

Jefferson paid Hemings wages while in France—an arrangement that sometimes gets cited as evidence of Jefferson’s benevolence. The more accurate reading is that wages were part of control: a way to incentivize performance while maintaining ownership. Even when Hemings’s pay was comparable to free domestic staff in later years, the core fact remained unchanged: his personhood was conditional in the eyes of the law that mattered most to Jefferson—Jefferson’s own.

Paris also complicated slavery’s certainties. In metropolitan France, slavery’s legal status was contested in ways that differed from Virginia’s brutal clarity, and Hemings moved through a city where Black people existed in a wider spectrum of social positions. He studied French seriously enough to hire a tutor—an act of intellectual ambition that reads, across the centuries, like a refusal to be reduced to a tool. A family account preserved in later narratives suggests that James and Sally Hemings contemplated staying in France, where they could plausibly claim freedom. Whether or not Hemings formally pursued a legal case, the possibility itself mattered. Once you have stood near a door marked “exit,” captivity becomes psychologically—and politically—harder to enforce.

Hemings returned to the United States with Jefferson in 1789. It is tempting to narrate that return as choice, loyalty, family obligation. It may have been all of those. It was also, inescapably, coerced.

The American Capital, the French Table

The United States government moved like a young animal in those years—awkward, hungry, improvising. In 1790, Jefferson, now Secretary of State, relocated to New York City, the temporary capital. Hemings ran the kitchen in a leased house on Maiden Lane, a detail that feels almost cinematic: the future of the republic simmering in rented rooms, statecraft conducted over plates carried by an enslaved chef who had trained in Europe.

This is where Hemings’s story begins to intersect with a specific kind of American myth: the dinner as history.

In late spring 1790, Jefferson hosted what he later called a meal “to save the Union”—a small dinner where political leaders tried to broker an agreement over federal assumption of state debts and the location of the nation’s permanent capital. Scholarly treatments and archival projects note Hemings’s likely role in preparing that meal, placing him in the kitchen while the United States negotiated itself at the table.

There is a seductive symbolism here—food as lubricant for compromise—and it is not wrong. But it risks turning Hemings into a metaphor rather than a person. The more human question is simpler: what did it feel like to be indispensable to the performance of American democracy while being excluded from its definition?

When the capital moved to Philadelphia later in 1790, Hemings followed, cooking for a revolving cast of American elites—cabinet members, congressmen, European diplomats, and visitors who wanted a taste of the new country’s refinement. Monticello’s historical materials describe Hemings receiving “market money” and making purchases, moving among free and enslaved workers, and likely learning that Pennsylvania’s legal context offered different possibilities than Virginia’s. Even within bondage, knowledge could be a kind of contraband.

Hemings’s food during these years is often reduced to a few headline dishes—macaroni pie, ice cream, meringues, crème brûlée. The fixation is understandable: these are recognizable markers of “French” taste, and they show how American cuisine absorbed European technique. But the deeper point is structural. Hemings brought with him a system: copper cookware, stew stoves, layered sauces, pastry techniques, the choreography of a formal meal. He helped translate French culinary language into an American accent, and he did so under conditions where authorship was not his to claim.

Negotiating Freedom in a Country Built on Enslavement

By 1793, Jefferson’s tenure as Secretary of State was ending, and he planned to return to Monticello. For Hemings, that return meant something stark: leaving places where slavery’s grip could be contested and returning to a state where it was enforced with near-total authority.

That year, Jefferson wrote a “Promise of Freedom” for James Hemings—an agreement that has survived as a chilling artifact of conditional personhood. Dated September 15, 1793, it promised Hemings emancipation after he trained a replacement “in the art of French cooking.” The document sits in the Library of Congress’s Jefferson materials as a blunt illustration of how freedom could be bartered: not granted as a right, but earned as a service rendered to the enslaver’s convenience.

This bargain is often summarized as Jefferson “keeping his word.” The more honest framing is that Hemings forced Jefferson into a contract. The agreement acknowledges Hemings’s leverage: Jefferson had invested in his training and depended on his skill. Hemings, in turn, recognized the power of his own indispensability. In a system designed to deny bargaining power to enslaved people, he bargained anyway.

The condition was cruelly intimate. Hemings was required to train his younger brother, Peter Hemings, to replace him. It is difficult to read that arrangement without feeling the violence of it: family turned into a mechanism for continuity of exploitation. Yet it also suggests Hemings’s pragmatism. If freedom was going to be achieved, it would be achieved through the channels the system allowed—however bitter those channels were.

On February 5, 1796, Jefferson signed a deed of manumission freeing James Hemings. The University of Virginia’s Jefferson collections preserve the deed, and the Library of Congress notes the fulfillment of the promise. Against the scale of Jefferson’s slaveholding—hundreds of people over his lifetime—the manumission stands out as an exception that proves the rule. The Library of Congress has noted that Jefferson manumitted or allowed only about ten enslaved people to escape bondage, and all were members of the Hemings family. Freedom, in Jefferson’s world, remained selective, strategic, and tethered to his interests.

Hemings was now free. But “free” in the early republic did not mean safe, equal, or stable.

A Free Man, a Haunted Republic

After emancipation, Hemings moved through a country where Black freedom was precarious and often punished. He worked in northern cities, including Philadelphia, and later Baltimore. His life becomes harder to document here, which is itself part of the story. Enslaved people were systematically prevented from leaving paper trails; even after emancipation, Black lives were often recorded only when they intersected with white interests or official scrutiny.

One of the most vivid surviving documents directly connected to James Hemings is not a recipe or a letter. It is a handwritten inventory of kitchen utensils at Monticello—practical, specific, almost mundane. The list is a reminder that mastery is built from objects and routines: knives, pots, pans, tools. It is also a reminder of how much of Hemings’s interior life—the ambitions, resentments, joys, relationships—remains inaccessible.

In 1801, Jefferson offered Hemings a position cooking at the White House. Hemings declined—an act that can be read as self-preservation, pride, exhaustion, or all three. After years of being bound to Jefferson’s household, the prospect of returning—this time as a free employee among “strange servants,” negotiating wages and conditions—carried its own risks. Accounts of this exchange survive through intermediaries, reflecting Hemings’s caution and Jefferson’s persistent desire to reattach Hemings’s talent to Jefferson’s brand.

Then comes the ending that refuses neat interpretation. In 1801, Jefferson received confirmation that Hemings had died by suicide, with the “general opinion” that excessive drinking was a cause. Monticello’s historical narrative treats the circumstances as unresolved and asks the questions historians cannot answer: depression, alcoholism, the psychic toll of “freedom without equality.” Annette Gordon-Reed, the Pulitzer Prize–winning historian of the Hemings family, has described Hemings’s death as tragic and his struggles as unknowable in detail, even as the broader context—racism, isolation, precarity—presses in around the edges.

If Hemings’s life were a novel, this ending might feel like an author’s insistence on bleak realism. In history, it feels like an indictment of the republic Hemings helped feed: a country capable of consuming Black brilliance while offering little shelter for Black humanity.

The Food, the Credit, the Theft

James Hemings’s legacy has been flattened into culinary trivia because trivia is comfortable. It allows Americans to admire his contribution without confronting the system that extracted it.

Take macaroni and cheese. The dish’s deeper origins stretch across continents and centuries, but in the American mythos it is often linked to Jefferson. More recent mainstream histories have emphasized what should have been obvious: Jefferson did not personally “invent” it; Hemings, trained in France, helped adapt and popularize a macaroni pie that became an American staple. This correction matters not because it changes the taste of the dish, but because it changes the meaning of the table.

Modern Black cultural and food-writing spaces have insisted on that correction for years. Word In Black, discussing Netflix’s High on the Hog, places Hemings alongside other foundational Black chefs like Hercules Posey and highlights how their careers and struggles shaped American foodways even as specific menus and portraits remain elusive. That elusiveness—the lack of portraits, the missing menus—is not accidental. It is what happens when a people’s artistry is treated as service rather than authorship.

It is also why Hemings’s story resonates beyond cuisine. He represents the broader pattern of cultural appropriation under slavery: Black creativity laundered through white names; Black labor turned into white refinement; Black skill framed as evidence of the enslaver’s “good taste.”

The most revealing part of the macaroni-and-cheese myth is not that Jefferson got credit. It is how easily the country accepted that he deserved it.

Cooking as Power, Cooking as Constraint

In the 18th century, elite cooking was not merely domestic. It was political technology. A formal dinner signaled education, cosmopolitanism, and control. Jefferson understood that. Hemings operationalized it.

Eater’s reporting on early Black celebrity chefs describes Hemings as apprenticing with French specialists and being paid wages comparable to free servants while still considered property—an arrangement that .

White House History’s account underscores how Hemings’s role continued as Jefferson moved through New York and Philadelphia, and how his bargaining for freedom emerged as Jefferson’s government service ended in 1793. In other words: Hemings’s bid for emancipation was timed to political transition, when Jefferson’s dependence on him was vulnerable. It was strategy. It was also survival.

To name Hemings as a foundational American chef is not to romanticize his bondage. It is to recognize the full complexity of skill under coercion. Enslaved cooks often held a paradoxical position: close enough to power to see it; valued enough to be protected at times; controlled enough to be trapped. That tension can produce a certain kind of excellence—an excellence that is not proof of slavery’s “benefits,” but evidence of human resilience and the violence of a system that commodified it.

The Archaeology of a Life, the Recovery of a Name

In 2018, reports noted that archaeologists at Monticello uncovered remains of stoves in the kitchen spaces associated with Hemings’s work—material traces of labor that had long been treated as backdrop to Jefferson’s story. The discovery was widely circulated because it offered something rare: physical evidence of Hemings’s professional world, not just Jefferson’s dining room.

But the deeper recovery is not archaeological. It is narrative.

In recent years, Hemings has reentered public consciousness through a combination of scholarship, museum interpretation, and popular media. The Guardian, writing about High on the Hog, invoked Hemings as an example of Black ingenuity during slavery and pointed to the misattribution that has long obscured figures like him. Word In Black similarly places him in a lineage of Black culinary founders. These references matter because they reshape public memory: Hemings is no longer a footnote in Jefferson’s biography; Jefferson becomes a complication in Hemings’s.

Even the broader cultural debate about how plantations tell their stories—what gets centered, what gets softened—has influenced how audiences approach Hemings. The Atlantic’s criticism of plantation narratives that erase slavery’s brutality sits in the background of any serious discussion of Monticello today: you cannot tell the “food story” without the labor story, and you cannot tell the labor story without confronting sexual coercion, family separation, and the violent economics of ownership.

Hemings’s significance, then, is not only that he cooked French food in America. It is that his life exposes how America learned to call exploitation “culture.”

What James Hemings Means Now

To write about James Hemings in 2026 is to write inside a shifting landscape of historical accountability. It is to watch institutions and media finally concede what Black communities and scholars have long asserted: that American culture—including American cuisine—was built through Black genius under conditions designed to erase that genius’s authors.

The correction is not merely about naming Hemings. It is about changing the grammar of American history. Instead of saying “Jefferson introduced French cuisine,” we are forced to ask: who learned it, who executed it, who endured it, and who benefited? Instead of treating the Hemingses as orbiting characters around a Founding Father, we are asked to treat the Founding Father as one powerful node in a larger human network—one that included people with talents, ambitions, and agency constrained by terror.

Hemings’s story also complicates a contemporary hunger for uplifting narratives. There is inspiration here—his determination to learn, to negotiate, to push against the boundaries of his circumstance. But the story does not resolve into triumph. Freedom arrives late, conditional, and costly. The end is sorrowful and opaque.

That is not a flaw in the story. It is the point.

James Hemings is significant because he refuses the nation the comfort of an uncomplicated hero tale. He forces America to hold two truths in the same mouth: that extraordinary beauty can be produced under extraordinary violence, and that a country can praise refinement while practicing barbarism.

At Monticello, visitors can now learn his name more easily than they could a generation ago. But the real test is whether they can sit with what his name implies. Hemings was not an accessory to Jefferson’s lifestyle. He was a central architect of an American culinary identity—and a witness to America’s founding hypocrisy, lived at stove-heat, day after day, in rooms that rarely made it into the portraits.

If you want to honor him, it is not enough to credit him for a dish. You have to credit him with a truth: the United States was fed by people it refused to recognize as fully human. And when those people demanded recognition—demanded contracts, demanded freedom—the nation’s greatest men treated that demand as a private inconvenience rather than a public reckoning.

James Hemings cooked the early republic its most delicious illusions. He also, by the mere fact of surviving and insisting, helped expose them.

More great stories

The First Derby Was a Black Derby