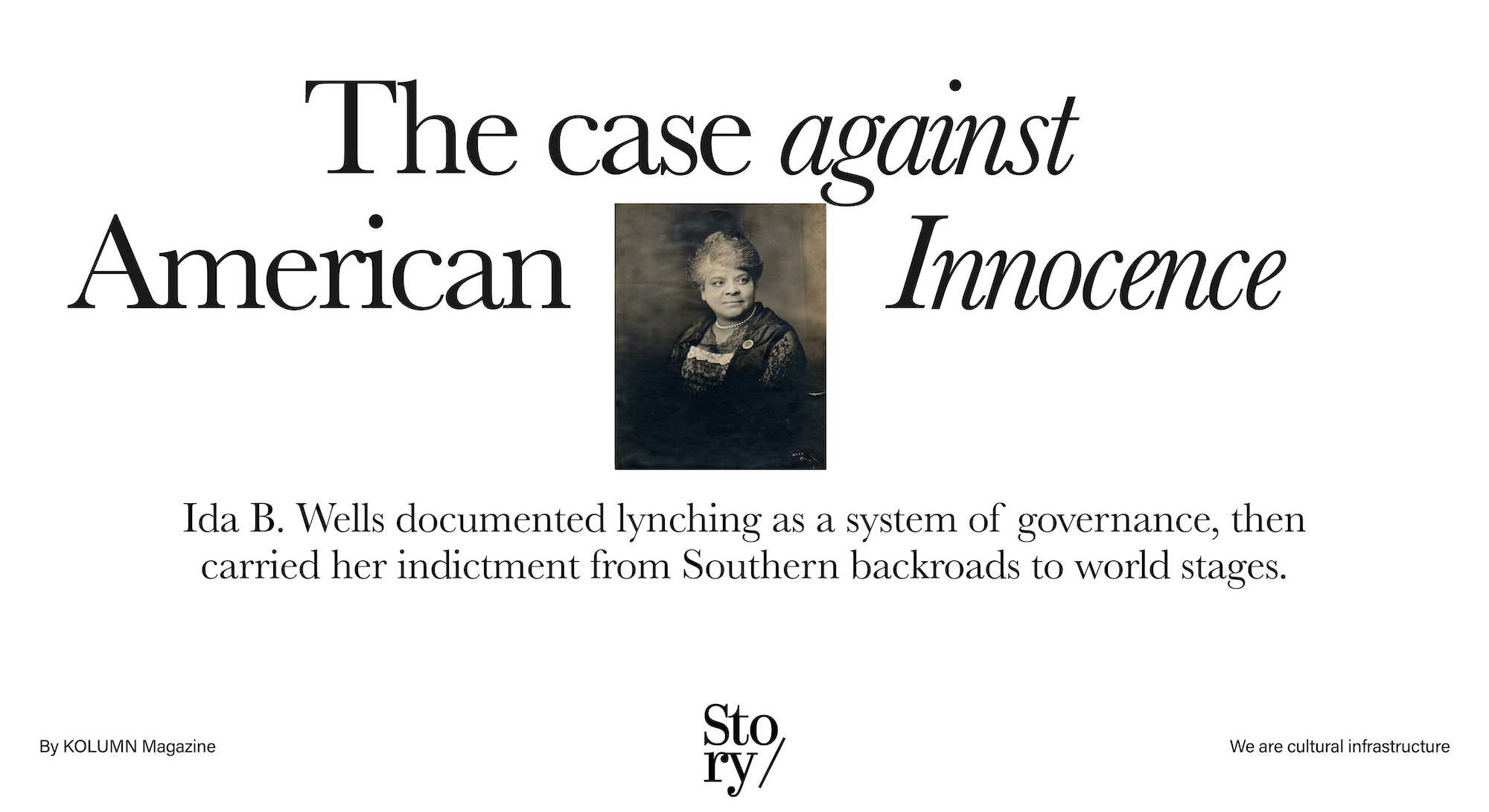

Wells performed a moral audit of the United States at a time when the nation was eager to declare itself healed after the Civil War.

Wells performed a moral audit of the United States at a time when the nation was eager to declare itself healed after the Civil War.

By KOLUMN Magazine

There are lives that read like prophecy only because they were lived as argument—days arranged into evidence, years spent insisting that what a nation calls “custom” is often just crime that has learned to dress itself. Ida B. Wells belonged to that category of American figure that the country both manufactures and resists: the citizen who refuses the comfort of myth, the writer who does not accept a convenient explanation because it is popular, the organizer who treats the public record not as neutral terrain but as a battleground.

Long before “investigative journalism” became a professional label and long before “human rights” became a common civic vocabulary, Wells practiced a method that looks startlingly modern: she chased patterns, compared accounts, tracked incentives, and compiled statistics in order to puncture a national story line. Lynching, she argued, was not a regrettable excess of frontier justice. It was not a series of spontaneous eruptions. It was a system—public, repetitive, and political—meant to police Black freedom after emancipation. And crucially, she insisted that the system depended on narrative as much as it depended on rope: the lie that lynching was the righteous punishment for a particular kind of crime, the lie that mobs acted when courts failed, the lie that white innocence needed violent protection.

Wells did not merely protest. She investigated. She did not merely mourn. She counted. In pamphlets, editorials, speeches, and painstaking tallies, she built an archive of American racial terror that challenged the press of her era and anticipated the tools of later movements. In 2020, the Pulitzer Prizes awarded Wells a posthumous Special Citation for “outstanding and courageous reporting” on the violence of lynching—an institutional acknowledgment arriving nearly a century after her most dangerous work.

But Wells’s significance is larger than a belated honor. She matters because she clarified something the United States still struggles to admit: that public violence can be a form of policy, that “law and order” can be a slogan masking disorderly cruelty, and that the press—when it refuses to accept official explanations—can function as a democratic emergency service. Wells practiced journalism not as commentary, not as branding, but as a form of survival work for a people whose deaths were often uncounted and whose suffering was routinely described as deserved.

A childhood inside the unfinished promise of emancipation

Ida B. Wells was born in 1862 in Holly Springs, Mississippi, in the middle of the Civil War, into a world where freedom was a battlefield term as much as a legal status. That birthplace matters not simply as biography but as context. Mississippi would become a laboratory for post-Reconstruction disenfranchisement, white terror, and the invention of a racial order enforced by both law and extra-legal violence. Wells’s life unfolded inside that experiment.

After the war, the Reconstruction era offered fragile possibilities: formal schooling for Black children, civic participation, institutions led by newly freed people. Wells would be shaped by the promise of education and the constant threat that the promise could be revoked. Later accounts of her life—archival summaries, biographies, and historical exhibitions—converge on the idea that she belonged to the first generation of Black Southerners for whom literacy and political aspiration were not merely dreams but obligations.

Then came catastrophe. In 1878, the yellow fever epidemic tore through parts of the South, killing tens of thousands and devastating families. Wells lost her parents and a sibling, and—still a teenager—assumed responsibility for the rest of her younger brothers and sisters. The details of that pivot are not just sentimental origin-story material; they are central to understanding her. Wells learned early that institutions could fail, that the social safety net for Black families was often a fiction, and that survival required both discipline and audacity. Those traits would later become visible in her reporting style: brisk, confrontational, unwilling to indulge the reader’s desire to look away.

She became a teacher—one of the respectable professions available to educated Black women in the late nineteenth century—and moved through the widening geography of Black aspiration: from Mississippi to Tennessee, from local classrooms to the larger public sphere. The teacher’s habit—preparing lessons, producing evidence, instructing a resistant audience—never left her.

The train car and the lawsuit: An early rehearsal for public combat

In 1884—decades before Rosa Parks—Wells was forcibly removed from a train car after refusing to give up her seat. The incident is often told as an anticipatory echo of later civil-rights iconography, and the comparison is tempting. But the more revealing detail is what Wells did next: she sued.

That choice mattered. Lawsuits are a kind of narrative contest: two sides present facts, interpretations, and legitimacy. Wells understood that the story of the incident—who belonged where, who counted as a “lady,” whose comfort mattered—was part of the machinery of segregation. She also understood that a public challenge creates a record. Even when courts disappoint, they can be forced to leave paper behind.

Contemporary and later histories emphasize that Wells initially won damages in a lower court before the decision was overturned at a higher level, with costs imposed against her. The lesson was bitter and instructive: the legal system could be invoked, but it was not neutral. Still, the episode positioned her as a figure willing to go public, to risk ridicule, and to insist on rights as something more than polite request.

This early conflict foreshadowed her mature political style. Wells was not interested in symbolic victory alone; she wanted consequences. Yet she was also pragmatic about the uses of defeat. If a system exposed itself as biased, that exposure could be ammunition.

Memphis and the making of a journalist

Wells’s most formative professional years unfolded in Memphis, Tennessee, where she became a newspaper editor and writer associated with the Free Speech (often referenced as the Memphis Free Speech). In the late nineteenth century, Black newspapers were not simply publications; they were institutions of community leadership, political education, and economic coordination. Editors were expected to be moral voices and tactical thinkers. The Black press did not merely report events. It trained readers in interpretation, pointed toward collective action, and served as a counter-public against white mainstream newspapers that frequently either ignored anti-Black violence or rationalized it.

Wells’s voice sharpened in that environment. Her prose was direct, unembarrassed by anger, uninterested in respectability as a substitute for justice. She wrote as someone who believed that information is a form of power and that power is necessary because appeals to sympathy are unreliable. Her writing had targets: white civic leaders who allowed violence, white newspapers that repeated the mob’s excuses, and Black leaders who she believed sometimes compromised too easily for access or safety.

Then a single Memphis event detonated her life and her legacy.

People’s Grocery and the moment the crusade begins

In 1892, three Black men connected to a Black-owned grocery—Thomas Moss, Calvin McDowell, and Henry Stewart—were lynched in Memphis after a conflict rooted in economic competition and neighborhood power. Wells knew Moss personally; the lynching was not an abstract outrage but a wound. This intimacy is crucial: Wells’s anti-lynching campaign began not as an academic project but as a response to the death of friends and to the casual certainty with which white Memphis moved on.

The “official” story that often followed lynchings in the era was familiar: the victim had committed, or was accused of committing, a heinous crime—often sexual assault against a white woman—and the mob acted as a surrogate for justice. Wells refused to accept that script. She investigated the People’s Grocery lynching and framed it as something else: an assault on Black economic independence and civic presence. Her editorials urged a boycott and encouraged Black Memphians to leave the city if they could, treating migration as a form of political pressure.

That intervention triggered retaliation. While Wells was out of town, a mob destroyed the newspaper’s press and threatened her life, effectively exiling her from Memphis. The story is often told as a tragedy—one woman silenced by terror. It is also a story of escalation. If Wells had remained a regional editor, she might have been remembered as a powerful local voice. Exile forced her into a national and international arena. It also clarified the stakes of her work: telling the truth could cost you your livelihood, your home, your safety.

Wells carried the lesson into everything she did afterward. She would not treat violence as exceptional; she would treat it as the predictable consequence of a racial order that required fear to function.

“Southern Horrors” and the refusal of the standard excuse

In the months after the Memphis lynchings, Wells began publishing her research and analysis in forms designed for circulation: pamphlets that could travel, speeches that could be repeated, arguments that could be quoted. One of her most famous early texts, Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases (1892), directly confronted the central lie that sustained lynching’s public acceptability: that mobs lynched Black men to protect white women from rape.

Wells’s move here was not simply moral but methodological. She treated the allegation as a hypothesis and the public record as data. She examined cases, compared accusations with outcomes, and pointed to patterns that contradicted the standard claim. She argued that consensual relationships—sometimes initiated by white women, sometimes rooted in the coercive racial and economic hierarchies of the South—were frequently re-described as “rape” when exposure threatened white reputations. She also argued that many lynchings had nothing to do with sexual accusations at all and were instead linked to labor disputes, political participation, and economic competition.

This argument scandalized polite society because it attacked not only lynching but the gendered mythology that excused it. Wells insisted that white womanhood was being used as a civic shield for white supremacy. She did not romanticize Black men; she was not claiming saintliness. She was claiming, instead, that the legal and moral standards applied to Black life were structurally dishonest.

That insistence on structural dishonesty—on the idea that the system’s official explanations are often crafted to protect the system—would become one of her enduring contributions to American political thought.

The ledger: The Red Record and the birth of data-driven civil-rights reporting

If Southern Horrors was a declaration, The Red Record (1895) was an infrastructure project: a statistical and narrative compilation of lynchings that sought to overwhelm denial through documentation. Wells tabulated lynchings by alleged cause, geography, and time, and paired numbers with stories that exposed the disparity between accusation and evidence.

In an era when official institutions often refused to count lynchings accurately—or treated them as local matters unworthy of national intervention—Wells constructed a public ledger. The significance of this cannot be overstated. Data is not merely descriptive; it is political. Counting creates visibility. Visibility creates pressure. Pressure can create policy.

Wells’s counting was also a direct challenge to the mainstream press. Many white newspapers either endorsed lynchings, minimized them, or reprinted the mob’s allegations as fact. By compiling cases and categorizing causes, Wells exposed the press’s complicity. She showed how narrative laundering works: a murder becomes “justice,” a mob becomes “citizens,” a victim becomes “brute,” and the reader is invited to accept the transformation as natural.

Modern readers may recognize this as a precursor to later forms of accountability journalism—projects that assemble databases of police violence, document patterns of voter suppression, or map environmental racism. Wells was doing this before the term “muckraker” became common currency, before the Progressive Era canon formed, and before the nation had language for “racial terrorism.”

The international stage: Turning American shame into global scrutiny

Wells understood that the United States—especially in the post-Civil War era—cared about its global reputation. She also understood that domestic institutions could be insulated by local power. One way to puncture that insulation was to internationalize the story.

She traveled and lectured, including in Great Britain, drawing attention to lynching and to the American South’s post-emancipation racial order. The Library of Congress’s interpretive materials note her wide lecturing and her willingness to go directly to sites of killings despite danger—an early example of on-the-ground reporting that refused to accept distance as safety.

International audiences sometimes responded with a moral clarity that American audiences resisted. That dynamic—outsiders naming American brutality more bluntly than Americans were willing to—became a recurring feature of U.S. civil-rights history. Wells leveraged it early. She used the world’s attention as a kind of external accountability mechanism.

This also had a cost. Critics framed her as airing dirty laundry, as threatening American unity, as exaggerating. Those criticisms themselves reveal her effectiveness. When a nation is more offended by exposure than by the crime exposed, the work of witness becomes revolutionary.

Chicago: Institution-building and the politics of respectability

After Memphis, Wells’s life and work became anchored in Chicago, a city that offered both opportunity and its own forms of racial segregation, political corruption, and economic stratification. Here, Wells expanded beyond journalism into broader institution-building: civic clubs, reform organizations, suffrage groups, and anti-lynching campaigns that demanded federal action.

She married Ferdinand L. Barnett, a lawyer and editor, and became known as Ida B. Wells-Barnett, though her public identity often retained the sharper brand of “Ida B. Wells.” Chicago’s Black political world could be a tough ecosystem: class tensions, ideological differences, and debates about strategy were constant. Wells—famously uncompromising—did not always make easy alliances. The Atlantic’s assessment of her suffrage politics emphasizes that her insistence on direct political action unsettled more cautious contemporaries, and that her gender amplified the skepticism she faced.

The point is not that Wells was difficult for the sake of it. It is that she treated compromise as something that required justification. She did not accept gradualism as wisdom merely because it sounded moderate. If a strategy asked Black people to wait, to soften their demands, or to accept partial inclusion, Wells often read it as a demand for permanent subordination dressed up as patience.

That stance produced conflict—including with prominent Black male leaders and with segments of the white suffrage movement—but it also produced clarity. Wells forced allies to explain the terms of their alliances. She forced movements to confront who was being left behind.

Suffrage and segregation: Refusing to march at the back

Wells’s place in the women’s suffrage movement reveals one of her most durable lessons: that progress for “women” was often constructed around white women’s needs, while Black women were treated as liabilities. In 1913, during the Woman Suffrage Procession in Washington, D.C., organizers attempted to segregate Black women marchers. Wells refused to comply, stepping into the Illinois delegation rather than marching in a separate group.

This moment is sometimes packaged as a single symbolic defiance. But its deeper significance is strategic: Wells understood that movement images become movement memory. If the suffrage movement’s public face was segregated, the resulting victory would likely preserve segregation’s logic. In other words, if you accept humiliation in the march, you will be offered humiliation in the policy.

Wells’s suffrage work in Chicago included the formation of political organizations such as the Alpha Suffrage Club, which mobilized Black women as voters and civic actors—an insistence that suffrage was not merely a moral claim but a power project. Later reflections and historical journalism continue to stress her role as a Black suffragist who rejected being sidelined.

Her significance here extends beyond the anecdote. Wells embodied an intersectional political analysis before the term existed: she understood that racism and sexism were not separate obstacles encountered on different days but overlapping structures shaping the same life. Her insistence that Black women must be full participants—visible, credited, centered—was not personal vanity. It was a theory of change.

The NAACP and the tensions inside “unity”

Wells is often described as a founder or early builder of major civil-rights organizations, including the NAACP, though accounts of her formal place in founding narratives have been subject to debate and institutional amnesia. The Library of Congress notes her role as a founder of the NAACP, and broader histories align on her importance to early twentieth-century Black reform networks.

What matters for understanding Wells is not just whether her name appeared on a particular list, but what her relationship to institutional politics reveals. Wells was an organizer who believed that institutions should serve the truth, not manage it. She did not always accept the “unity” argument when unity required silence or moderation. She was willing to break ranks, criticize allies, and risk isolation if she believed the stakes demanded it.

This is a difficult legacy for institutions to celebrate, because institutions prefer founders who can be safely monumentalized—heroes whose sharp edges can be sanded down for plaques and ceremonies. Wells’s edges were part of her method.

Journalism as a counter-court: Evidence against civic denial

Wells’s anti-lynching work is sometimes remembered as advocacy rather than journalism, as if the two are mutually exclusive. That distinction misunderstands both her era and her purpose. Wells practiced a form of journalism that treated the public as a jury and the newspaper column as a courtroom.

She gathered witness accounts. She cross-checked claims. She identified conflicts of interest: white newspapers repeating allegations from sheriffs, sheriffs aligned with local elites, elites invested in suppressing Black competition. She understood that to argue effectively, you had to show not only that violence happened but that the official explanations were unreliable and self-serving.

Modern rhetorical scholarship and archival projects preserve the text of her speeches and editorials, emphasizing how she embedded evidence—cases, statistics, quotations—into persuasive structure. Even when she used moral language, she anchored it in documentation.

This was radical because it reversed the typical burden of proof. The default posture of white America was to assume that a lynched Black person must have done something to deserve it. Wells refused that presumption and demanded evidence from the accusers. She insisted that accusation is not proof, that rumor is not law, and that “public sentiment” can be manufactured.

In doing so, she advanced an idea that remains urgent: that the health of a democracy depends on whether its citizens demand proof before accepting violence as justified.

Economic motives and the mythology of “crime”

One of Wells’s most provocative contributions was her insistence that lynching was often linked to economic control. She pointed out that Black success—owning businesses, acquiring land, competing with white enterprises—could trigger violence framed as moral or criminal outrage. In this view, lynching functioned as an enforcement mechanism for racial capitalism: a way to discipline Black ambition and protect white economic dominance.

This line of analysis has been echoed and re-examined by later journalism and scholarship, including reporting that highlights how Wells connected lynching to economic resentment and the suppression of Black competition.

The point is not that every lynching can be reduced to economics. Wells herself documented a range of alleged causes and exposed the flexibility of the mob’s justifications. The deeper point is that the “crime” story was often a cover story. Lynching was not simply “punishment”; it was communication. It told Black communities: there are limits to what you may become.

Wells’s insistence on motive—on asking why this person, why now, who benefits—is another way she looks like a contemporary investigative reporter. She treated violence as a social act embedded in power relations, not as a random moral failure.

The long arc toward federal recognition—and the stubbornness of delay

For much of Wells’s life, the federal government failed to enact meaningful anti-lynching legislation despite repeated campaigns, petitions, and public pressure. The political reasons are familiar: Southern lawmakers’ power in Congress, the national parties’ dependence on segregationist blocs, and the unwillingness of many white Americans to prioritize Black safety.

Wells’s activism included efforts to petition national leaders. Later reflections, including commentary tied to the eventual passage of federal anti-lynching law in the twenty-first century, highlight how long this fight lasted and how early Wells pressed it.

The delay itself is part of her significance. Wells stands as a representative of the generation that exposed a national crime yet lived long enough to see how slowly exposure translates into policy. The distance between truth and consequence is a lesson her career teaches relentlessly.

When the Pulitzer Board recognized her work in 2020, it did more than honor a single journalist. It implicitly acknowledged an institutional failure: that American journalism’s highest honors had largely overlooked the Black women whose reporting was often the bravest, and that the violence Wells documented was not peripheral but central to American history.

Why Wells still feels contemporary

It is easy to praise Wells in language that turns her into a sepia-toned moral emblem: fearless, pioneering, ahead of her time. But if we leave her there, we miss what makes her truly important. Wells does not merely belong to history. She haunts the present because her questions remain unresolved.

She asked: What happens when local power can kill with impunity? What happens when the press repeats official narratives rather than interrogating them? What happens when “respectability” becomes a demand placed on the oppressed rather than the oppressor? What happens when movements pursue partial victories that leave the most vulnerable exposed?

Her work also clarifies something about evidence. Wells understood that facts do not speak for themselves. They require infrastructure: collection, publication, circulation, repetition. They require courage because evidence threatens those who benefit from ignorance. She built that infrastructure with the limited tools available to a Black woman in the nineteenth century—pamphlets, speeches, Black newspapers, lecture tours—and made it powerful enough that it could not be entirely erased.

Even the attempts to marginalize her—excluding her from some organizational narratives, framing her as too radical, treating her as inconvenient—are part of her modernity. Social movements still struggle over credit, visibility, and whose anger is considered legitimate.

The afterlife of her work: Monuments, memory, and the battle over narrative

In recent decades, Wells’s public memory has expanded through books, documentaries, museum exhibits, and commemorations. This revival is not simply a feel-good story of belated recognition; it is also a contest over how the nation understands its past. To honor Wells is to admit that lynching was not a footnote but a chapter, and that the people who documented it were often treated as agitators rather than as truth-tellers.

The movement to commemorate her—in Chicago especially—has been chronicled in mainstream outlets, emphasizing how rare it has been for Black women reformers to receive prominent public memorials.

But commemoration carries risks. A statue can freeze a person into a single meaning. Wells’s life resists that. She was not only an anti-lynching crusader; she was also a suffragist, a political strategist, a community organizer, and a critic of both white and Black leadership when she believed they were wrong. She was also, as some personal essays and family reflections emphasize, a human being with vanity, fatigue, contradictions, and domestic frustrations—traits that do not diminish her but make her more real.

The challenge of remembering Wells honestly is the challenge of honoring her method, not just her bravery. Her method demands that we ask hard questions of our own era. Who is being terrorized today, and what stories are used to justify it? Who is doing the counting, and who benefits when counting is absent? What “common sense” narratives are actually ideological cover?

Wells’s legacy inside Black journalism and Black feminist thought

Wells is sometimes called a blueprint for Black women journalists, and the phrase is not hyperbole. Her career models a professional ethic: do not outsource your moral judgment to institutions that have already shown their bias; document with rigor; publish with urgency; accept the consequences because the alternative is complicity.

Black media commentary and historical journalism have repeatedly returned to Wells as an ancestor of contemporary reporting on state violence, racial terror, and gendered power—an ancestor not in the soft sense of inspiration but in the technical sense of method and risk.

Her influence on Black feminist politics is equally structural. Wells’s life dramatizes how Black women were forced to fight on multiple fronts: against white supremacy, against sexism within reform movements, against exclusion inside supposedly universal campaigns. The now-common idea that race and gender are intertwined in lived experience has older roots in the practice of women like Wells, who did not have the vocabulary of later theory but lived the reality that theory describes.

The insistence that Black women must be seen as political actors—not as symbols, not as auxiliaries—runs through Wells’s work. It is present in her refusal to march behind, in her organizational leadership, in her willingness to confront white women reformers who used racist tropes, and in her constant return to the idea that democracy cannot be real if it is selective.

A final measure of significance: Wells and the moral audit of the United States

What does it mean, finally, to call Ida B. Wells significant?

It means acknowledging that she performed a moral audit of the United States at a time when the nation was eager to declare itself healed after the Civil War. She showed, with case after case, that the war’s end did not end racial domination—it reorganized it. She demonstrated that the line between “legal” and “illegal” violence was often thin, with sheriffs, judges, and editors serving as enablers even when they were not the ones holding the rope.

It also means acknowledging that Wells expanded the definition of journalism. She treated reporting as a form of democratic defense for people who could not rely on the state for protection. She fused narrative with statistics, witness testimony with structural analysis, and local investigation with international advocacy.

And it means admitting something uncomfortable: Wells’s work remains relevant because the mechanisms she exposed—narrative justification for violence, institutional reluctance to intervene, the stigmatization of truth-tellers as agitators—still operate.

In 1895, when Wells published The Red Record, she was doing something more than compiling atrocity. She was declaring that the nation’s conscience should be forced to operate on facts, not on myths. That demand—simple, radical, and still unmet in many arenas—is why her name continues to matter.

More great stories

Romare Bearden: Harlem, In Panels