Her life—and the state’s handling of it—demonstrates how Jim Crow justice could bind together race, gender, and class into a single rope: a legal system that was willing to imagine a white man’s violence as “discipline,” a Black woman’s resistance as “assault,” and a Black child’s defense of his mother as “murder.”

Her life—and the state’s handling of it—demonstrates how Jim Crow justice could bind together race, gender, and class into a single rope: a legal system that was willing to imagine a white man’s violence as “discipline,” a Black woman’s resistance as “assault,” and a Black child’s defense of his mother as “murder.”

By KOLUMN Magazine

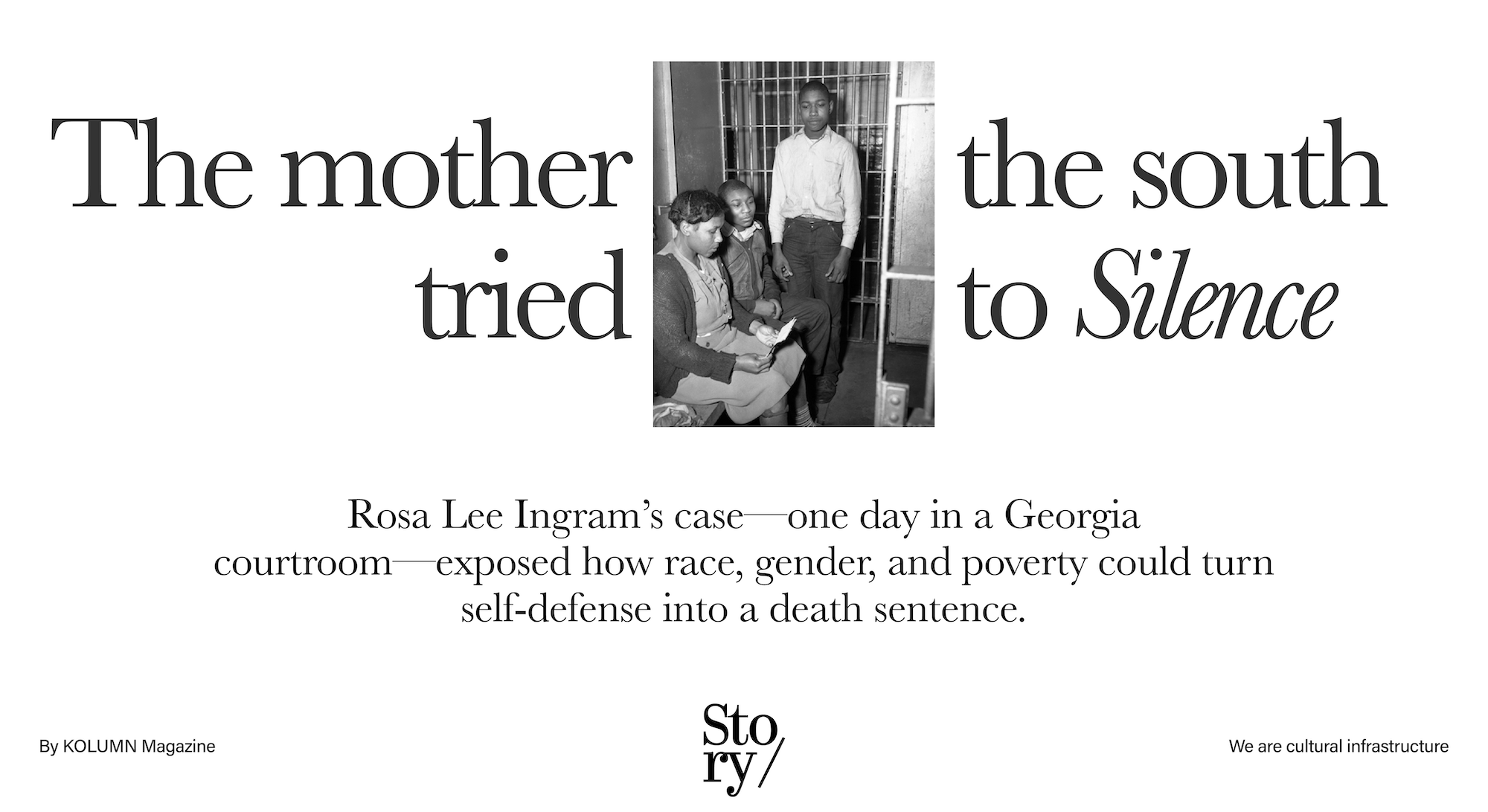

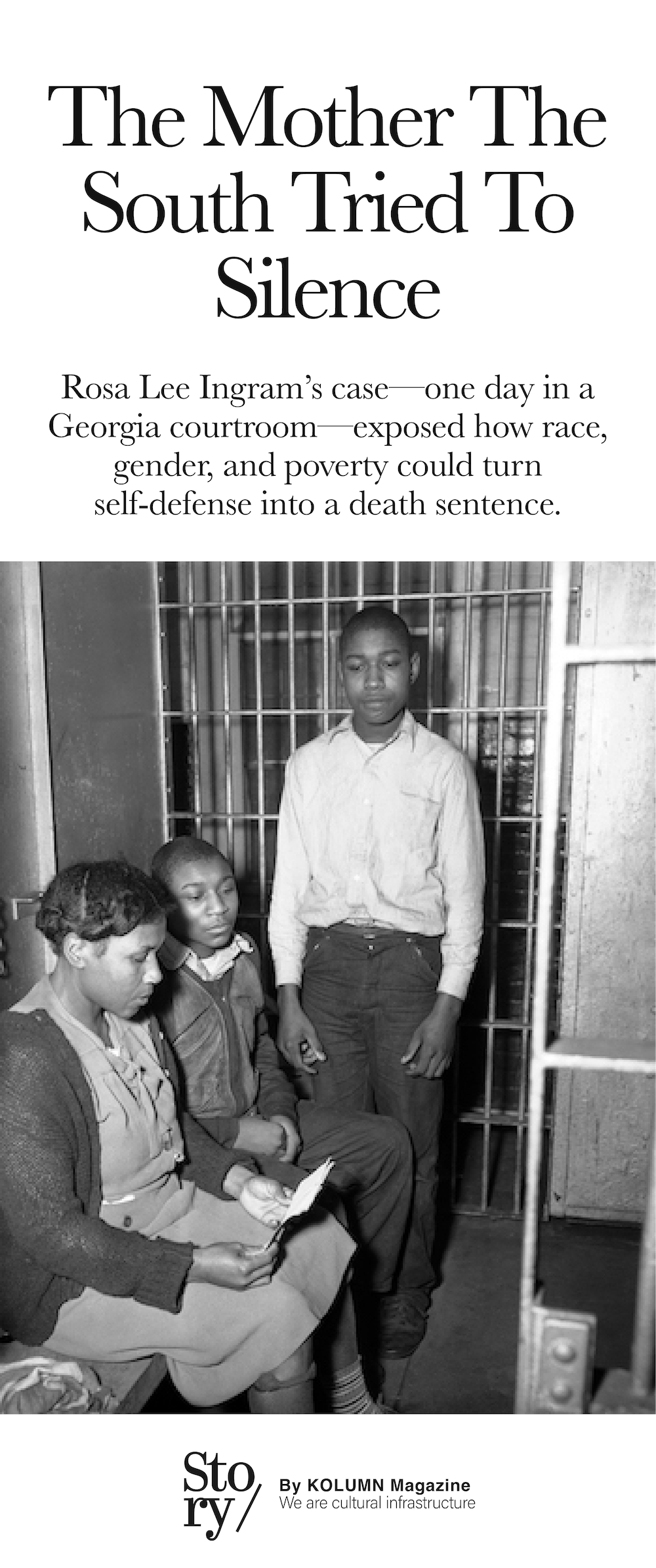

The most frightening cases in American legal history are not always the ones with the most complicated facts. Sometimes they are frightening precisely because the mechanics are simple: a poor defendant, an overmatched defense, a community primed to presume guilt, and a courtroom that moves with the speed of inevitability. In January 1948, in Ellaville, Georgia, the state put that machinery on display. Rosa Lee Ingram—a Black, widowed sharecropper and mother of twelve—and two of her sons were tried in a proceeding so brief that it has lived on in the historical record as a one-day trial. When it ended, the verdict treated a Black woman’s survival as a capital offense.

Ingram’s name is not as widely known as Rosa Parks’s, Emmett Till’s, or even the Scottsboro Boys’—yet the Ingram case sits squarely in the lineage of American “legal lynching,” a category historians and advocates use to describe court proceedings that functioned as ritualized punishment when extrajudicial terror risked political blowback. It also belongs to a more specific, often under-taught sub-history: the criminalization of Black women’s self-defense against sexual violence and the way their children’s protection of them could be turned into proof of “criminality.” The Ingram case galvanized national protest, helped consolidate new forms of Black women’s organizing, and provided an early Cold War crucible in which civil rights work, anti-communism, and human-rights language collided—sometimes productively, sometimes disastrously.

Rosa Lee Ingram’s significance is therefore not only biographical. It is structural. Her life—and the state’s handling of it—demonstrates how Jim Crow justice could bind together race, gender, and class into a single rope: a legal system that was willing to imagine a white man’s violence as “discipline,” a Black woman’s resistance as “assault,” and a Black child’s defense of his mother as “murder.” The story is also about what happens when people refuse that script: how pressure campaigns, petitions, church networks, Black newspapers, labor groups, and left-led legal organizations built enough national attention to force the state to retreat—first from execution, then, more slowly, from indefinite imprisonment.

A life shaped by land, loss, and the arithmetic of survival

Rosa Lee Ingram was born in 1902 and died in 1980, spending most of her life in Georgia’s rural Black Belt, where the sharecropping system—ostensibly a post-slavery labor arrangement—often operated as economic captivity. Widowed and responsible for a large family, she lived inside a world where “independence” was measured in tiny increments: the ability to keep livestock, to negotiate the terms of planting and harvesting, to maintain some control over one’s children’s labor, and to endure the daily humiliations that white landlords and white neighbors treated as their prerogative.

Ingram’s story is easiest to understand if you begin with the ground itself. Sharecroppers worked land they did not own. They paid for seed and supplies on credit at ruinous terms. They settled accounts at harvest, under the supervision of the same people who controlled the books. The “freedom” to leave was often an illusion; debts, threats, and local law enforcement were the enforcement mechanism. For Black women, this economic vulnerability was compounded by exposure to sexual harassment and assault from white men who could weaponize both social power and physical violence. These dynamics are not abstract context for the Ingram case; they are the environment in which the defining confrontation occurred.

Accounts differ in emphasis, and responsible reporting has to mark that clearly. Some summaries foreground a dispute about livestock and property boundaries. Other reporting—particularly in the Black press and later scholarship—argues that the confrontation was entangled with a longer pattern of sexual harassment and threats by the white man who would end up dead. What is consistent across sources is that the encounter was violent, that Ingram was struck, that her sons responded, and that the legal system read the family’s defense not as mitigation but as aggravation.

The confrontation: One rural fight, an entire country watching

On November 4, 1947, a white man named John Stratford confronted Rosa Lee Ingram near Ellaville in Schley County, Georgia. According to later summaries, he was armed; the altercation escalated quickly; and Ingram was struck—hit with the butt of a rifle in versions preserved by civil-rights advocates and later historical work. Her sons rushed in when they heard her screams. Stratford died from blows delivered during the struggle.

What happened next is the part that turns a tragic encounter into a national scandal. Ingram and multiple sons were arrested. The case moved toward trial at a pace that, in retrospect, seems designed to prevent organized defense. In January 1948, Rosa Lee Ingram and two sons—Wallace and Sammie Lee—were tried in Ellaville by Judge W. M. Harper. The trial lasted a single day. Ingram’s lawyer, S. Hawkins Dykes, was appointed essentially at the last moment—on the eve of the proceedings, according to the New Georgia Encyclopedia. The jury was all white, a routine feature of Jim Crow courtrooms that nonetheless demands to be stated plainly when the defendants are Black and accused of killing a white man.

The speed matters because speed is a kind of power. A defendant with money can hire counsel early, investigate facts, locate witnesses, consult experts, and build a story that competes with the prosecution’s narrative. A defendant without money—especially in a system structured to treat Black defendants as presumptively guilty—gets something else: a courthouse performance whose outcome is largely pre-written. The Ingram trial is repeatedly remembered for this imbalance: a widowed mother of twelve meeting her court-appointed lawyer effectively at the threshold of the courtroom, facing a state that could marshal law enforcement, local witnesses, and cultural assumptions about race and “proper” social order.

The verdict was severe. Rosa Lee Ingram and the two sons on trial were convicted and sentenced to die in the electric chair—despite the sons’ ages and despite the circumstances that supporters argued amounted to self-defense. The execution date was set quickly, amplifying panic and urgency.

“Legal lynching” in a suit and tie

In the popular imagination, lynching is a rope and a tree, a mob and a body. The term “legal lynching” exists because, in the mid-20th-century South, the formal institutions of law could serve similar ends: rapid convictions, inflated charges, inadequate defense, coerced testimony, and punishments designed to reaffirm racial hierarchy. The Ingram case became one of the most prominent late-1940s examples because it combined so many recognizable elements—racial hierarchy, gendered violence, class vulnerability—into a package that was hard to ignore.

There is an additional, specifically gendered dimension: the way rape and sexual coercion were simultaneously pervasive and legally unspeakable when the victim was Black and the perpetrator was white. In many Southern jurisdictions, white men’s sexual violence against Black women rarely produced consequences. Yet when Black women resisted—and when Black men or boys intervened—courts could treat that resistance as the real crime. In the Ingram case, defenders and later writers argued that Stratford’s actions and threats were sexual in nature, and that the family’s response should have been understood as defense against assault. The legal system, instead, rendered the white man as the victim whose death demanded the maximum penalty.

The backlash: Petitions, protests, and a coalition that made the state blink

The death sentences did not land quietly. Almost immediately, they triggered protests that stretched far beyond Schley County. Civil rights organizations, Black newspapers, labor activists, and left-aligned legal advocates treated the case as emblematic: if this could happen to a widowed sharecropper and her children, it could happen anywhere, and it revealed what “justice” meant when racial hierarchy was at stake.

Multiple sources emphasize the breadth of organizing and the centrality of Black women’s groups. The Equal Justice Initiative’s calendar entry frames the case as a moment that illuminates how Black women faced both racialized violence and the near-absence of legal protection, with the Ingrams’ eventual parole not arriving until 1959. The Yale Law Library, describing pamphlets in its collection, notes that the case generated nationwide press coverage and that African American women’s organizations were widely credited with helping win commutation and sustaining the long campaign that ultimately led to parole.

This is the part of the story that complicates easy narratives about “the” civil rights movement. Popular memory often centers male clergy, courtroom lawyers, and big-ticket Supreme Court decisions. The Ingram campaign, by contrast, shows a dense ecosystem of activism: petition drives, pressure on parole boards, visits to officials, fundraising for legal support, and the circulation of pamphlets meant to make an obscure rural case legible to national audiences.

It also reveals a crucial political tension. The NAACP was involved in efforts around the case, but so were organizations associated with the Civil Rights Congress and other left-led formations that, in the late 1940s, often took on Southern capital cases as part of a broader argument about American hypocrisy and human rights. That mix of participants helped generate reach and resources—while also, in the emerging Cold War environment, giving segregationist officials and federal investigators an opening to smear civil rights work as “communist agitation.”

A new kind of Black women’s politics

One of the most historically significant outcomes of the Ingram case is the way it catalyzed Black women’s organizing that did not fit comfortably inside the dominant narratives of the time. Later scholarship and archival notes repeatedly tie the case to the rise of groups such as Sojourners for Truth and Justice, a women-led organization that mobilized around the Ingram family and other human-rights concerns during the early Cold War.

The University of Illinois Library, writing about its holdings and historical context, describes how leftist groups worked on the case and how women who advocated for the Ingrams would go on to found or lead formations like Sojourners for Truth and Justice. The post also emphasizes that the commutation to life sentences did not end activism; supporters kept pushing for parole for years, underscoring how “victory” in such cases was often partial and provisional.

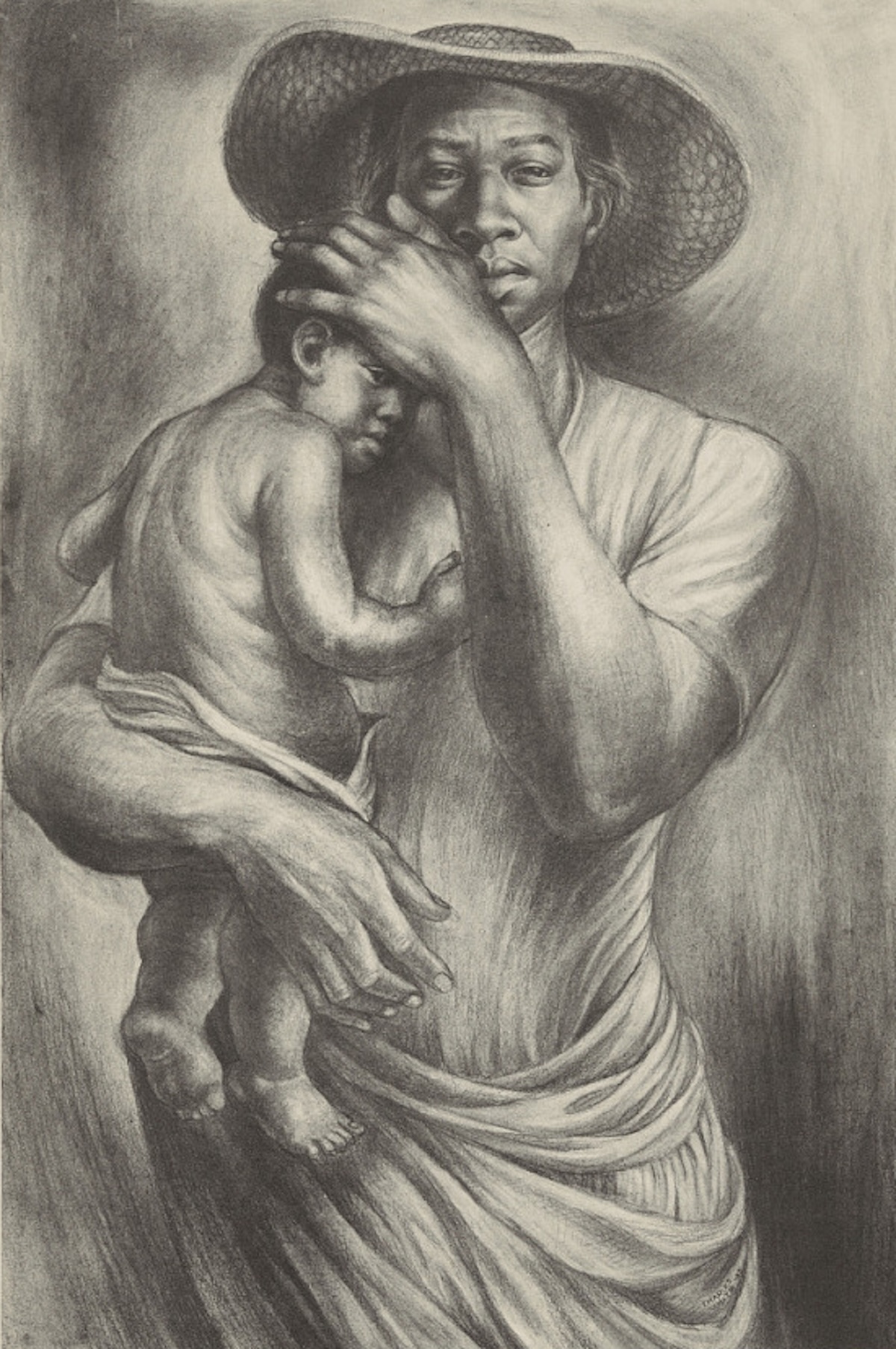

In many accounts, the Ingram campaign becomes a template for what we would now call an intersectional analysis—though the vocabulary did not exist at the time. The state’s narrative of the case required the public to imagine a white man’s violence as incidental and a Black mother’s resistance as deviant. Activists countered by insisting on a different moral center: Black motherhood as something worthy of protection, Black children’s defense of their mother as honorable, and sexual violence against Black women as a public matter rather than a private shame.

Commutation: A retreat, not an exoneration

Under mounting pressure, the legal outcome shifted. The trio’s death sentences were commuted to life imprisonment. In many sources, this moment is described as a response to public outcry and post-trial motions, with the Georgia Supreme Court later affirming convictions and life sentences. The commutation saved their lives, but it preserved the state’s core claim: that the Ingrams’ actions were not self-defense but murder deserving permanent punishment.

This is one of the hardest truths about mid-century racial justice campaigns: the system often “compromised” in a way that avoided the spectacle of execution while keeping the underlying conviction intact. From the state’s perspective, this could be framed as mercy. From the activists’ perspective, it was a concession extracted by pressure—a sign that officials feared the national embarrassment of executing a mother and her teenage sons under such circumstances.

The long middle: Years in prison, years of organizing

After commutation, the case entered its most exhausting phase: the long middle in which the emergency has passed, attention drifts, and the state relies on time to do what it could no longer do openly. This is where Black women’s organizing proved decisive. The New Georgia Encyclopedia notes repeated parole requests denied through the 1950s and emphasizes that, even when officials expressed willingness to parole the Ingrams in 1957, it took two more years for the board to vote in favor of release.

The Yale Law Library, reflecting on its pamphlet acquisitions, similarly highlights the extended timeline: commutation to life, then release on parole only in 1959. That arc matters because it clarifies what “success” required. Saving the Ingrams from execution was not a single battle won by a single march. It was a decade-plus project that demanded institutional memory, fundraising, media strategy, and repeated confrontation with bureaucratic indifference.

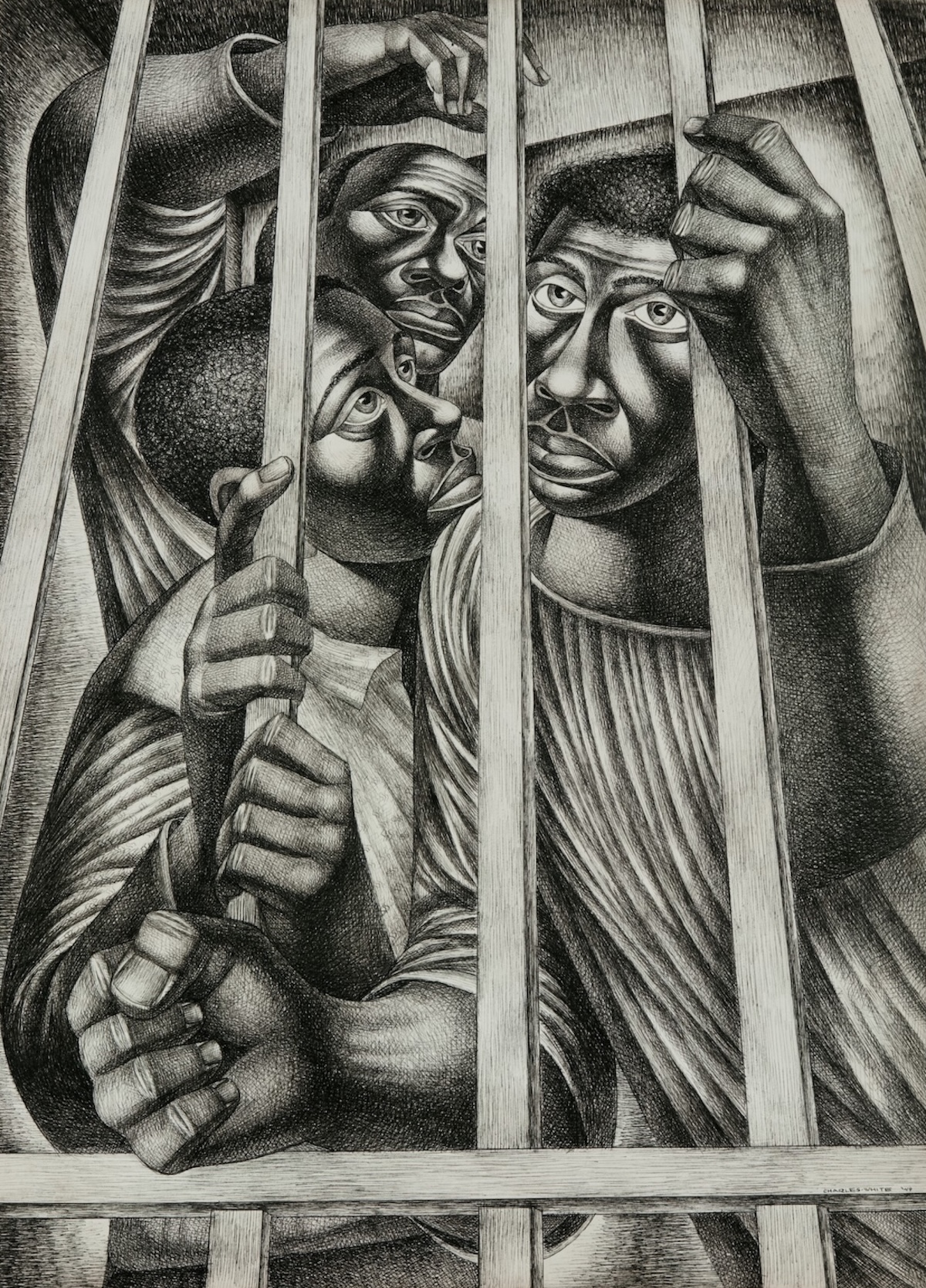

During this period, the case also became a cultural object—a symbol reproduced in pamphlets and, later, in art. The Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture holds a print titled Ye Shall Inherit the Earth, tied in museum documentation to “The Ingram Case” set, underscoring how artists and cultural workers treated the story as emblematic of Black dignity under siege.

Parole and release: The state yields, quietly

On August 26, 1959, Rosa Lee Ingram and her sons were released on parole. The date appears repeatedly in institutional summaries of the case, including the New Georgia Encyclopedia. Contemporary Black press coverage also documented the moment. The Atlanta Daily World reported on the paroles, offering a reminder that Black newspapers remained crucial institutions for telling stories that mainstream outlets covered sporadically or through hostile frames.

Parole is not vindication. It is conditional freedom, wrapped in the implication that the prisoner remains, in some sense, properly punished. Yet in the Ingram case, parole was still a marker of what organized pressure could accomplish. It represented an admission—unspoken but real—that the state could not hold the family forever without continuing political cost.

After her release, Ingram lived in Atlanta until her death in 1980. In many sources, this is where the narrative ends: the woman returns to ordinary life, and history turns the page. But the meaning of the case was never confined to what happened to Ingram alone. It reverberated because it exposed the legal logic of Jim Crow and because it forced activists to invent tools and language that would shape later struggles.

Why Rosa Lee Ingram matters now

The modern tendency is to treat the mid-century civil rights movement as a march toward inevitability: Brown v. Board, Montgomery, Birmingham, Selma, Voting Rights Act—an arc of progress. Rosa Lee Ingram complicates that script in at least four ways.

First, her case shows how early the movement’s “gender problem” existed. Black women were not merely foot soldiers; they were often the reason campaigns sustained themselves over time. The organizing around Ingram prefigured later frameworks that explicitly linked racial justice to gendered violence and the protection of Black motherhood.

Second, it demonstrates that the criminal legal system was not separate from the civil rights struggle—it was central to it. The Ingram case was, at root, a fight over whether a Black family had the right to defend itself against armed assault. That question has not disappeared; it returns whenever self-defense law is unevenly applied, whenever prosecutors interpret Black fear as aggression, and whenever juries are asked to decide which lives are “reasonable” to protect.

Third, it illustrates the Cold War’s distorting effects. The involvement of left-led organizations and the circulation of Communist Party–affiliated pamphlets became part of the story not only because those groups did real work, but because anti-communism offered opponents a convenient way to discredit the underlying claim: that Jim Crow courts produced outcomes incompatible with democracy. Archival descriptions of pamphlet collections and institutional holdings make clear how central this print culture was to the case’s public life.

Fourth, Ingram’s story forces an honest confrontation with how history is curated. Some cases become civic myths; others become footnotes. The reasons are not always about importance. They are often about narrative convenience. Rosa Parks offers a clean parable of dignity and protest. Rosa Lee Ingram offers something messier: a rural conflict entangled with gendered violence, poverty, and a legal system so shameless it nearly executed children. It is harder to package, and perhaps for that reason it is easier to forget—unless journalists, educators, and cultural institutions refuse to let it vanish.

The Ingram case as a mirror for “the everyday”

It is tempting to treat landmark cases as exceptions, as aberrations that the system later corrected. The Ingram case argues the opposite. Everything about it was ordinary for its setting: the racial hierarchy, the quick trial, the lack of meaningful defense, the all-white jury, the readiness to accept a white man’s violence as background noise, the harshness of punishment when Black people insisted on self-possession. What made it “special” was not the courtroom; it was the response—the fact that enough people, across enough places, decided that this particular instance of ordinary injustice would not go unanswered.

The most enduring image of the case may therefore be less about the fatal altercation and more about what followed: supporters gathering, petitions circulating, women demanding entry to the spaces of governance, and a state forced to calculate whether killing a mother and her sons was worth the cost. The NYPL photograph of supporters outside pardon and parole offices captures that slow confrontation with power: people standing, waiting, insisting—turning bureaucracy into a site of protest.

Rosa Lee Ingram’s place in American memory

Rosa Lee Ingram should be remembered alongside the figures we treat as foundational to modern civil rights history—not because her story is interchangeable with theirs, but because it illuminates dimensions they do not. It foregrounds Black rural life rather than urban organizing; motherhood rather than charismatic male leadership; self-defense rather than nonviolent protest as the moral center; and a criminal courtroom rather than a bus, a lunch counter, or a schoolhouse as the primary stage.

Her case also belongs to the longer tradition of Black women whose resistance to sexual violence was redefined as criminality. That tradition stretches backward into slavery, forward into the 20th century, and persists in contemporary debates about credibility, consent, and the unequal distribution of sympathy. The Ingram case, preserved through institutional summaries, archival pamphlets, and the work of historians, gives that tradition a specific face and timeline.

If you want a final measure of significance, consider what the state attempted: it tried to execute a mother and her teenage sons after a one-day trial in which meaningful defense was nearly impossible. It did not succeed—not because the system self-corrected, but because people forced it to stop. The lesson is not only about the cruelty of Jim Crow justice. It is also about the power required to interrupt it, and the kinds of organizing—often women-led, often unglamorous, often sustained for years—that make interruption possible.

More great stories

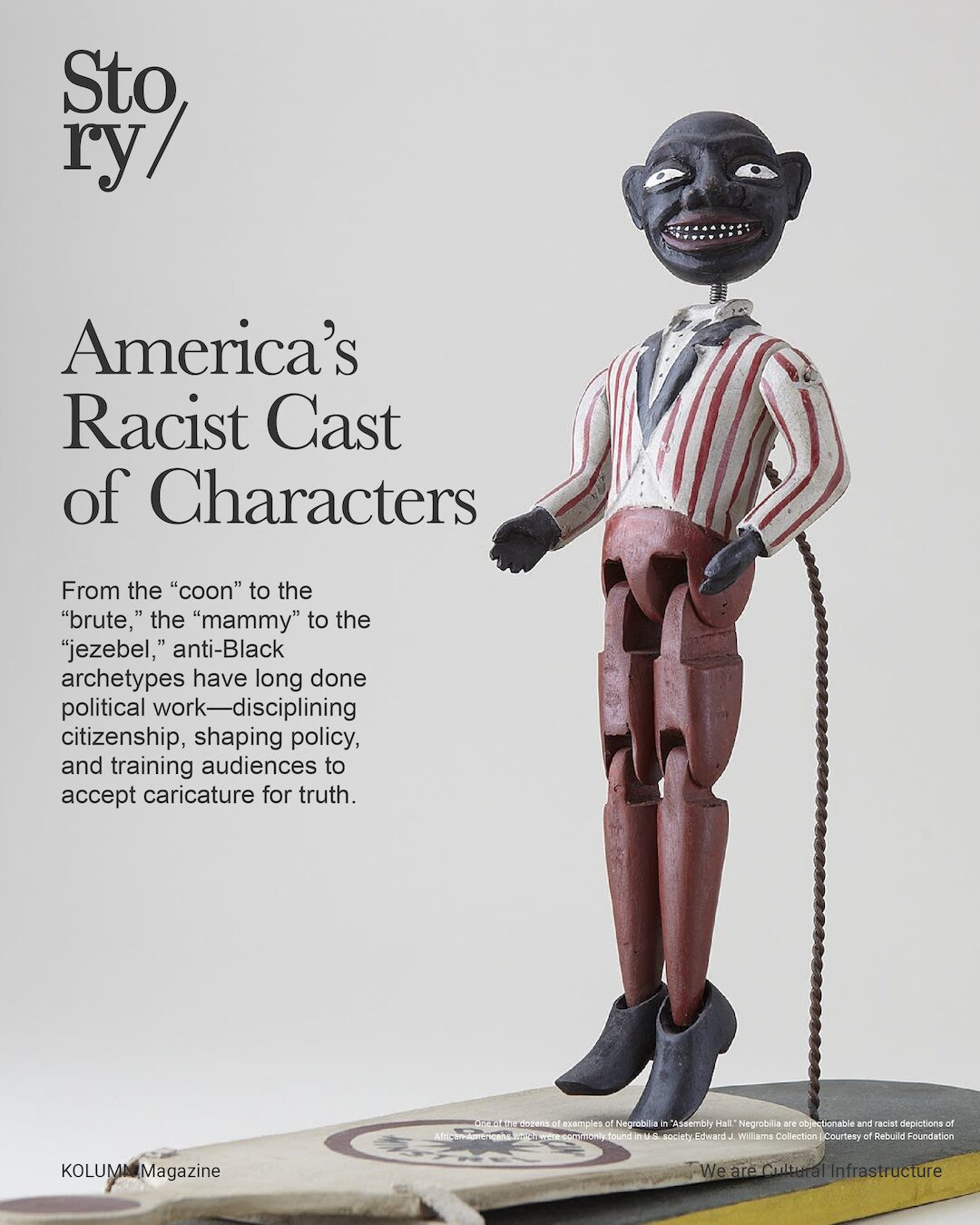

America’s Racist Cast of Characters