If Black women could “enter” as fully recognized human beings—educated, economically secure, politically empowered—then the nation would have to reconfigure its logic of hierarchy.

If Black women could “enter” as fully recognized human beings—educated, economically secure, politically empowered—then the nation would have to reconfigure its logic of hierarchy.

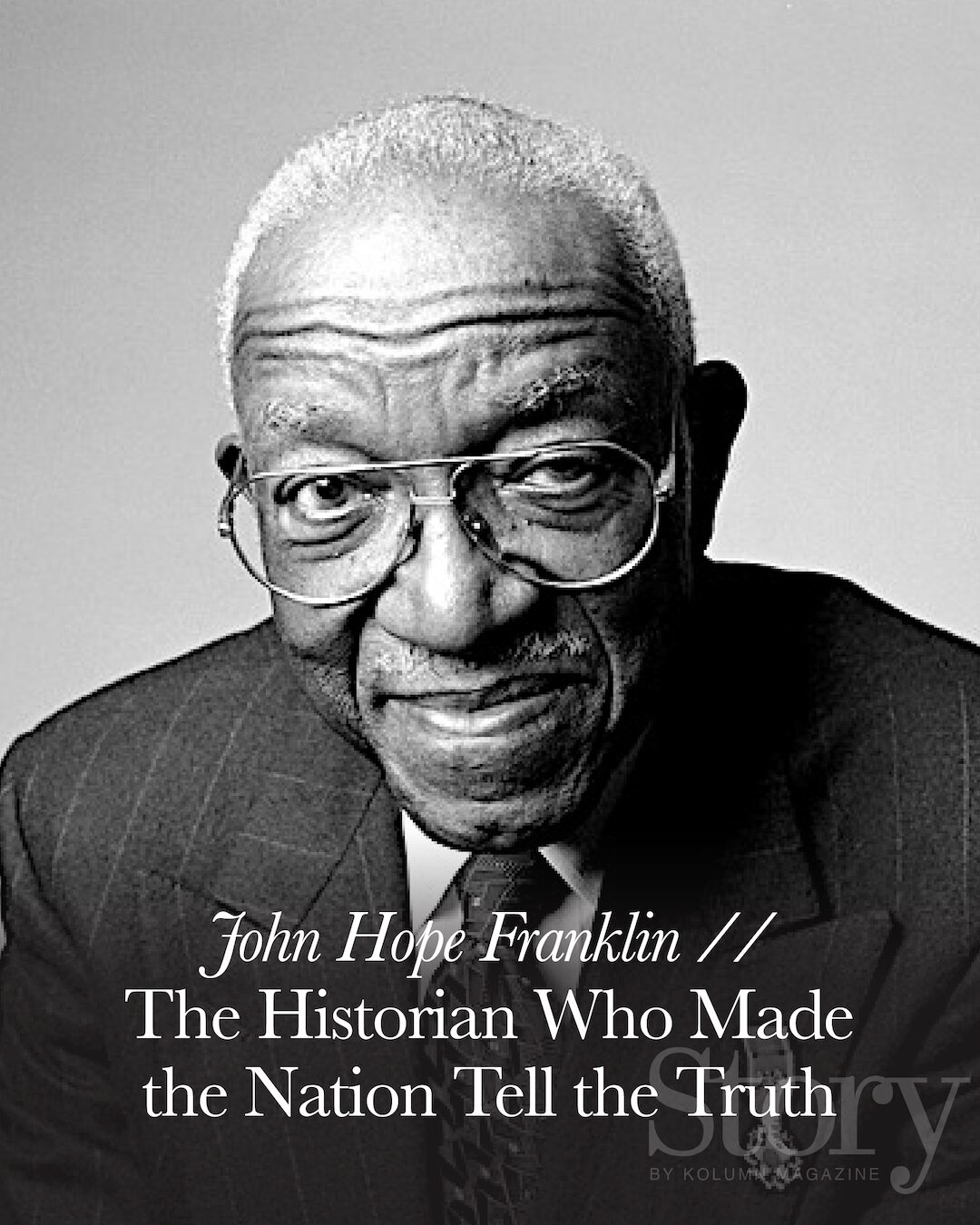

By KOLUMN Magazine

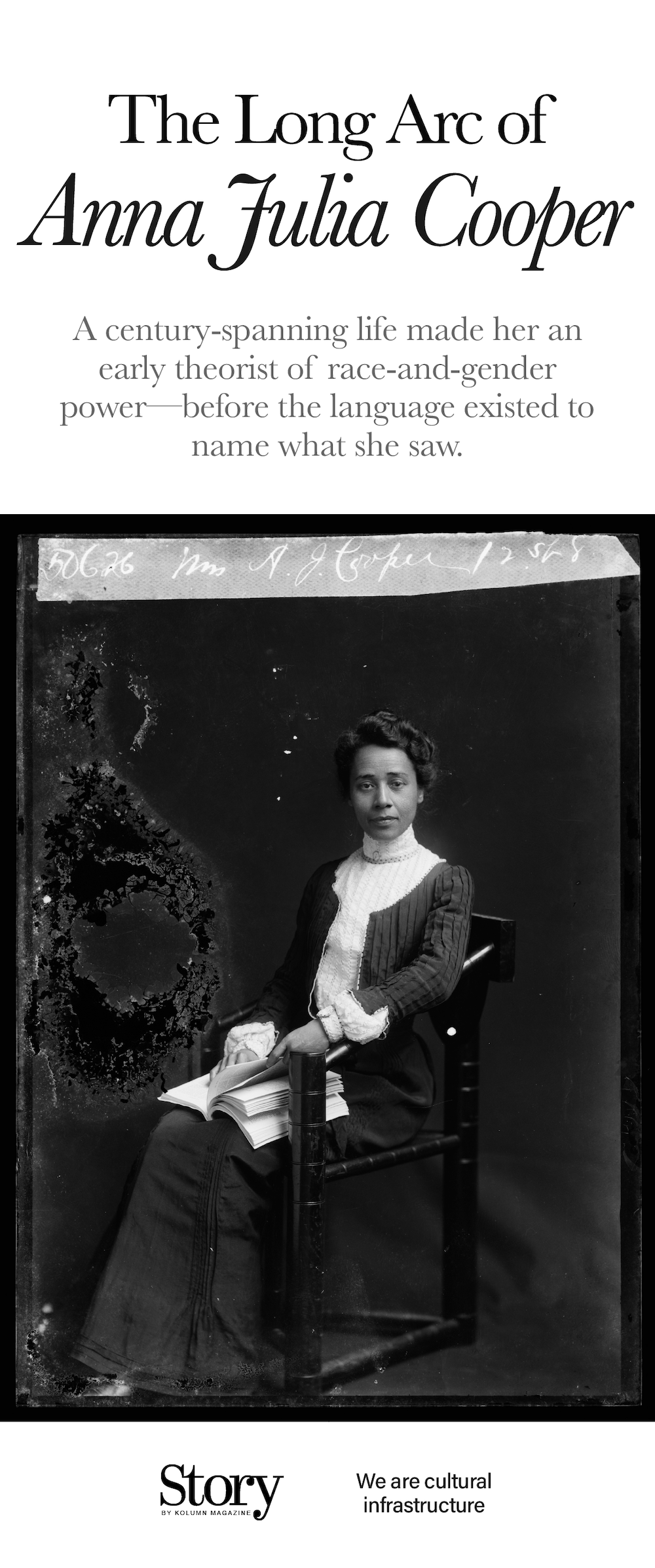

On a straightforward timeline, Anna Julia Cooper’s life can sound like a triumphal march: born enslaved in Raleigh, North Carolina, in 1858; educated with unusual intensity; widowed young; remade herself as a scholar; elevated generations of Black students in Washington, D.C.; published a foundational work of Black women’s political thought; then—long after most lives have settled into quieter late chapters—earned a doctorate from the University of Paris-Sorbonne and helped sustain an adult-education institution that served working-class people the formal system neglected. Her life ended in 1964, after a century that included Reconstruction, the tightening vise of Jim Crow, two world wars, and the modern civil rights movement.

But Cooper’s significance is not only that she did remarkable things. It is that she built an argument about power—how it is made, maintained, and sometimes punctured—that feels uncomfortably current. Before “intersectionality” entered academic vocabulary, Cooper wrote as if she had already mapped the terrain: race and gender were not separate problems, not parallel tracks, but forces that collided in Black women’s lives in ways the country refused to see. In A Voice from the South (1892), she insisted that the status of Black women was not a niche concern, not a “women’s issue” subordinate to racial justice or a “race issue” subordinate to women’s rights. It was a diagnostic: if America could not make room for Black women’s full humanity, it was not yet a democracy worth congratulating.

Cooper’s ideas were forged in institutions that trained her discipline and sharpened her sense of contradiction: an Episcopal school in the post–Civil War South; Oberlin College in Ohio; Washington’s elite Black educational circles; and the bureaucratic contest over what kind of education Black children “should” receive. Her career also unfolded amid a broader conflict inside Black America about strategy and dignity—debates later symbolized by Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. Du Bois, but lived out on school boards, in classrooms, and in the daily calculations of parents who wanted their children to survive and to rise. Cooper’s insistence on rigorous academics, and on Black women’s intellectual leadership, placed her at the center of that struggle.

The sources that remain—archival editions of her writing, institutional biographies, museum histories, and renewed cultural attention—reveal an enduring tension: Cooper’s prose could carry the moral language of her time while also cutting against the era’s assumptions. She could be simultaneously steeped in Victorian ideals of virtue and yet unafraid to name the structural degradation of Black women’s labor. She could speak in the register of uplift and still deliver an indictment: a nation that exploits “pinched and downtrodden” women cannot claim civilization.

What follows is not a hagiography. It is an account of how Cooper’s life became a platform—how she used education as both a credential and a weapon, how she navigated the politics of respectability without surrendering her critique, and how her writing helped build the intellectual lineage that later scholars would recognize as Black feminist thought.

Born into a world that expected silence

Cooper entered the world in Raleigh in 1858, in slavery’s late, brutal years. Multiple biographies and institutional profiles describe her as born to an enslaved mother, Hannah Stanley Haywood, and fathered by a white man tied to her family’s enslavement—details that matter not as sensational origin-story texture, but because they locate Cooper at the violent intersection of power, sex, and property that defined American slavery.

In the mythology America tells itself, emancipation is often framed as a door that opened, cleanly, into freedom. Cooper’s early life suggests something messier: opportunity appeared through institutions that were themselves complicated—often religious, sometimes paternalistic, occasionally transformative. She attended St. Augustine’s Normal School and Collegiate Institute (now St. Augustine’s University), an Episcopal institution established to educate freed people and train teachers and clergy. Accounts from women’s history and Episcopal archival resources emphasize her aptitude and her refusal to accept the gendered limits placed on what girls should study. She pressed into subjects coded as male—mathematics, advanced coursework, classical learning—not because she wanted to be an exception, but because she believed the line separating “women’s education” from “men’s education” was one of the country’s quiet tyrannies.

That insistence—girls have as much right to intellectual rigor as boys—seems obvious now. In Cooper’s youth, it was insurgent. Her early schooling also embedded a theme she would return to for decades: education as a portal, not merely to employment, but to citizenship and to moral authority. Later commentators, including museum historians, would highlight how she treated “culture”—languages, literature, history—not as ornamental refinement but as proof of equal capacity in a society organized around denying it.

She married George A. C. Cooper, a man connected to the institution, and was widowed within a few years. Biographical sketches tend to mention the marriage briefly and then move quickly to the aftermath: widowhood did not shrink her ambitions; it clarified them. The decision to pursue higher education after losing her husband reads, in many accounts, less like a pivot than a declaration—she would not be defined by the roles available to her.

Oberlin: The making of a scholar who would not accept partial access

Cooper’s subsequent years at Oberlin College are central to her later authority. Oberlin was one of the few institutions that admitted women and Black students in the nineteenth century, but the openness was qualified: curricula were stratified, and women were often steered toward “ladies’ courses” rather than the classical track. Cooper resisted this sorting. Accounts of her education emphasize that she pursued the curriculum typically reserved for men, completing a B.A. and later an M.A., including substantial work in mathematics and classical studies.

Here is where Cooper’s intellectual temperament becomes visible: she did not argue merely for access; she argued for the whole thing. Partial education, in her view, trained Black people and women to accept partial citizenship. This is not simply an abstract principle; it shaped her later battles with Washington’s school board, her insistence that Black students deserved advanced study, and her refusal to treat vocational training as the natural ceiling for Black ambition.

Oberlin also placed her among peers who would shape Black civic life, including figures connected to Black women’s organizing networks that later flourished in Washington. Even when biographies only gesture at these circles, they suggest an emergent community of Black women intellectuals who understood themselves as builders of institutions, not merely beneficiaries of them.

Washington, D.C.: A Black intellectual capital under siege

After Oberlin, Cooper moved into a Washington that functioned as both symbol and battleground. The city held a growing Black professional class and an ecosystem of churches, clubs, schools, and salons that cultivated debate and strategy. At the same time, Washington’s public institutions were governed through the politics of white control, and Black autonomy in education was perpetually contested.

Cooper joined the faculty at M Street High School, the elite Black public high school that later became associated with Dunbar High School’s legacy. A Washington Post opinion piece notes her recruitment to the M Street faculty in the late 1880s and emphasizes the stakes of her tenure: she entered at the moment when Black public schooling—and M Street in particular—faced attacks on its autonomy and ambitions.

M Street’s reputation was not accidental. It produced graduates who entered top universities and professional tracks, contradicting the era’s racist assumptions about Black intellectual capacity. Cooper taught subjects that signaled seriousness—Latin, mathematics, the classics—and helped maintain the school’s academic identity. Museum histories describe her as part of a faculty that demanded rigorous preparation, and they situate her later principalship within a conflict over whether Black students should be trained for labor or prepared for leadership.

This conflict is sometimes flattened into a Du Bois–versus–Booker T. Washington storyline. But in Cooper’s life, it showed up as policy: school boards pushing “industrial” education; administrators pressured to reduce classical offerings; and Black educators insisting that “practicality” was often code for containment. A 2024 Washington Post theater review of Tempestuous Elements—a play dramatizing Cooper’s tenure—frames the core dispute as one of equality of opportunity, with Cooper resisting leaders who would “ring-fence” educational advancement for white students.

Cooper did not deny the dignity of vocational work. The point, as later historical commentary summarized, was that Black children should not be forced into a narrower future by the prejudices of those who governed them. Education, in her view, was not merely workforce development; it was the cultivation of citizens capable of contesting injustice with competence and language.

“When and where I enter”: The thesis that made her unavoidable

In 1892 Cooper published A Voice from the South: By a Black Woman of the South, a text that modern publishers and historians describe as her signature work and one of the earliest sustained articulations of Black women’s political thought in the United States.

The book’s enduring line—often paraphrased as “when and where I enter”—has traveled far beyond its original context, showing up in contemporary political rhetoric and international development commentary. The Guardian, for example, invoked Cooper’s words as a call to center those most marginalized, emphasizing that equality cannot be achieved if those bearing multiple forms of oppression are left behind.

The line works because it compresses her entire argument into a claim about perspective and consequence. Cooper insisted that Black women’s entry into public life was not merely additive; it was transformative. If Black women could “enter” as fully recognized human beings—educated, economically secure, politically empowered—then the nation would have to reconfigure its logic of hierarchy. If they remained excluded, the rhetoric of progress would be a performance.

In the essays of A Voice from the South, Cooper wrote about education as the “lever” of racial progress, but she refused to treat women as supporting characters in a male-led racial narrative. She also refused to accept the women’s movement as it often existed: a movement that could demand rights while ignoring racial exploitation, and that could romanticize “womanhood” while leaving Black women with the burdens of labor and the vulnerabilities of sexual violence and economic precarity. The text’s power lies in its double critique: she challenged white supremacy and challenged gender hierarchy, sometimes within the same paragraph.

At points, Cooper’s rhetoric drew on Victorian ideals of moral refinement, a strategy that scholars have debated: did such language reinforce a politics of respectability, or did it tactically deploy the era’s moral code against the nation’s racism and sexism? What is clear is that Cooper used the language available to her to smuggle a radical premise into mainstream debate: Black women were not a “problem” to be managed; they were thinkers and leaders capable of diagnosing America’s failures.

It is important, too, that the book came from an educator, not a distant theorist. Cooper wrote as a woman who could point to outcomes: she taught Black children whose achievements directly contradicted the theories that justified their exclusion. Her classroom functioned as empirical rebuttal.

Clubwomen, institution-building, and the politics of the “ordinary” week

Cooper’s public life did not run solely through books and classrooms. Like many Black women leaders of her era, she moved through clubs, leagues, church networks, and reform organizations that functioned as a parallel civic infrastructure when formal power was denied. Institutional biographies note her involvement in Black women’s organizing in Washington, including ties to efforts that supported community welfare and women’s advancement.

This matters because Black women’s clubs were not social extracurriculars; they were governance experiments. They built childcare, mutual aid, moral reform programs, educational initiatives, and political pressure campaigns in a society that refused to protect Black lives. Cooper’s emphasis on education fit inside this landscape as both a principle and a practical project: schools were among the few places where Black communities could attempt to shape the future at scale.

Cooper also belonged to the circles of Black Washington’s intellectual life—salons and reading groups that reinforced the idea that Black people were not merely subjects of policy but producers of thought. Modern accounts of her Washington years emphasize how the city’s Black elite, despite being constrained by segregation and disenfranchisement, created spaces where ideas about race, empire, and democracy could be debated with sophistication.

The principalship and the backlash: What it means to “want too much” for Black children

In 1902 Cooper became principal of M Street High School. The title alone can mislead: principalship sounds administrative, managerial. In Cooper’s Washington, it was political. The principal controlled curriculum, teacher selection, academic standards, and therefore the school’s philosophy of who Black children could become.

That is why her tenure was fraught. The Washington Post opinion essay describing her role in D.C. education underscores how her leadership coincided with attacks on Black school sovereignty.

The pressure points were familiar: demands to shift toward vocational training; oversight by white male officials; suspicion of Black excellence when it threatened the racial order. Cooper insisted on the academic path—classics, foreign languages, advanced mathematics—not as an aesthetic preference but as a civil right. She believed the state had no moral authority to offer Black children a diminished education while offering white children the tools of leadership.

Her principalship became, in later cultural retellings like Tempestuous Elements, a dramatization of what happens when a Black woman refuses to accept institutional ceilings. The play’s focus, as reviewed by the Washington Post, centers on her conflict with white educational leadership at a time of racial gatekeeping.

The historical record, filtered through museum accounts and later profiles, indicates that her insistence on academic rigor triggered backlash that contributed to her removal. Even without treating every archival detail as fully settled, the pattern is clear: Cooper became a target because her school proved that Black children could excel under Black leadership and a demanding curriculum.

The lesson Cooper drew was not to retreat from rigor but to broaden the fight: curriculum was a battleground because it defined the nation’s future leadership. If Black students mastered the classics and entered elite universities, the ideology of racial hierarchy had to fight harder to justify itself.

International vision: The Pan-African horizon

Cooper’s thought was never only national. In 1900 she traveled to Europe and participated in the First Pan-African Conference in London, where she presented on what was often called the “Negro problem” in America—language of the era that she used to expose, rather than accept, the country’s contradictions. Multiple sources, including a National Park Service profile, note her participation and her European travel in that period.

This global horizon matters for two reasons. First, it positioned Black American struggles within a diaspora and an imperial world order; second, it reinforced Cooper’s belief that education and political power were inseparable. Anti-Blackness was not simply a local prejudice; it was part of a system that justified exploitation at home and abroad.

In this sense, Cooper’s Pan-African engagement anticipated later twentieth-century movements that connected civil rights to anti-colonial struggle. She belonged to an early cohort of Black intellectuals who treated the color line as global architecture.

The late doctorate: Scholarship as endurance, not ornament

Perhaps the most cinematic element of Cooper’s biography is the doctorate. Many profiles note that she earned a PhD from the University of Paris-Sorbonne in 1924, after decades of work and well into adulthood.

The doctorate is often framed as a capstone, but it also functions as a metaphor for Cooper’s method: she accumulated credentials not to satisfy institutions, but to expand her capacity to argue. In a society eager to dismiss Black women as unqualified, she became overqualified, turning the credential system into a platform for critique.

A Washington Post archival feature from the early 1980s, reflecting on public commemoration of Cooper, mentions her dissertation and notes it was written in French, underscoring the seriousness of her scholarship and the international dimension of her intellectual identity.

The Sorbonne doctorate also complicates how we imagine “theory.” Cooper’s theory did not emerge solely from reading; it emerged from a life spent building institutions, defending standards, and contending with power. Her scholarship was not an escape from politics; it was a way to sharpen political argument.

Frelinghuysen University and adult education: Dignity for people the system wrote off

In Cooper’s later decades, she became associated with Frelinghuysen University, an adult-education institution in Washington, D.C., that served working people. Biographical sources describe her leadership role there, including service as a president and registrar.

Frelinghuysen’s significance aligns perfectly with Cooper’s beliefs. If elite schooling was one front in the struggle, adult education was another. It treated working-class Black Washingtonians not as people whose education had “ended” but as people still entitled to intellectual growth. It also challenged the idea that learning belonged only to the young or the affluent.

There is something quietly radical in the image—preserved in institutional histories—of Cooper as an elder scholar still doing the work of education administration, still treating access to learning as a moral obligation.

How she sits in the lineage now: Black feminism before the label, education as civil rights before the slogan

Today, Cooper is often invoked as a forerunner of Black feminist thought. That framing can flatten her into a single category, but it also captures a truth: her work theorized the specific vulnerabilities and political power of Black women, insisting they were central to the nation’s progress. Modern essays in mainstream outlets still cite her as a crucial figure in Black women’s political history, and A Voice from the South continues to be reissued and discussed as foundational.

Her influence also runs through education debates. Cooper’s insistence on rigorous, classical education for Black students anticipates later arguments about equal protection, school funding, tracking, and the racial politics of “standards.” Even contemporary commentary about the need for Black teachers and Black-led schools echoes the logic of her era: leadership shapes expectations, and expectations shape outcomes.

Cooper’s work also remains relevant to the internal politics of reform movements. She lived in a time when women’s rights activism could be segregated by race and when Black political movements could marginalize women’s leadership. The Root, in a discussion of the long history of intersectional analysis, places Cooper among figures who fought for visibility within both women’s and civil rights movements.

That dynamic—movements asking Black women to wait their turn—still recurs. Cooper’s answer, then and now, is unsparing: if a movement cannot make room for those at the intersection of oppressions, it is not a movement for liberation. It is a movement for a rearranged hierarchy.

The Cooper paradox: Respectability language, radical outcomes

One of the most interesting tensions in Cooper’s legacy is stylistic. She often wrote in a moral register that can read, to modern ears, like respectability politics—virtue, refinement, uplift. It would be easy to dismiss her on that basis, to treat her as an artifact of Victorian constraints. But the outcomes she pursued were radical: full access to education, public authority for Black women, and a reordering of social power.

In other words, her diction sometimes sounded conservative while her demand structure was revolutionary. She wanted Black women not merely protected, not merely “included,” but recognized as the intellectual and moral center of social transformation. The Guardian’s invocation of her “when and where I enter” line captures how that demand travels: it is a claim that the most marginalized must be centered, not accommodated.

This paradox is also a reminder: liberation movements often use the language their era will permit, but they can still plant ideas that later generations radicalize further. Cooper’s work is a bridge—between abolition-era Black women’s oratory and the twentieth century’s formalized feminist and civil rights frameworks.

A century-long life, and the meaning of endurance

Cooper lived to 105. Commentators sometimes treat that longevity as trivia, but it has interpretive weight. She witnessed not only political change but changes in the vocabulary available to describe Black struggle. She saw the U.S. move from slavery to segregation to the early civil rights victories of the postwar era. She lived long enough to die in 1964, the same year the Civil Rights Act became law.

Longevity did not guarantee triumph; it guaranteed perspective. Cooper’s life is a reminder that progress is often incremental, contested, and reversible—and that the people who push it forward are frequently those denied the luxury of cynicism.

When you return to her signature idea—Black women’s entrance as a turning point—you can see it as both prophecy and method. Cooper entered every room she could: the classroom, the principal’s office, the intellectual salon, the Pan-African conference, the university system in Paris, the adult-education institution in Washington. She entered not to be exceptional but to widen the doorway.

That is the accomplishment beneath the accomplishments: she helped redesign the terms on which Black women could be seen—as thinkers, as leaders, as producers of theory, as architects of the future.

Jacob Lawrence: The Chronicle Painter