A belief that immigrants from poorer places are presumptively burdens, and that the state’s job is to refine the filters that keep burdens out.

A belief that immigrants from poorer places are presumptively burdens, and that the state’s job is to refine the filters that keep burdens out.

By KOLUMN Magazine

On February 5, 1917, Congress overrode President Woodrow Wilson’s veto to pass what would become one of the most consequential gatekeeping laws in U.S. history: the Immigration Act of 1917, sometimes called the Burnett Act. It did not establish the national-origins quotas that later defined the 1920s. It did something both simpler and, in its own way, more revealing. It tried to quantify human worth. It asked, with the confidence of a state turning prejudice into administration, whether a person could read, whether a person carried “defects,” whether a person might become a ward of the public, whether a person came from the wrong geography—and then, based on those proxies, whether that person could possibly add value to American society.

That is why the law remains such a useful mirror. Not because the United States of 1917 maps neatly onto the United States of 2026—its demographics, its labor markets, its geopolitics, its legal doctrine all differ. The parallel is more fundamental than context. The 1917 statute crystallized a governing philosophy that returns whenever immigration is treated less as a social reality than as a sorting problem: the belief that immigrants from poorer places are presumptively burdens, and that the state’s job is to refine the filters that keep burdens out.

A century later, the Trump administration has re-centered that belief—sometimes explicitly, sometimes through bureaucratic architecture that makes the belief operational. In his first term, Trump’s rhetoric frequently wandered into the open contempt of hierarchy—his reported “shithole countries” remark in a 2018 meeting is now part of the era’s public record, as is the contrast he drew between immigrants from places like Norway and immigrants from Haiti and African countries. In his second term, which began January 20, 2025, the administration’s posture has taken a more system-building form: executive actions suspending refugee admissions on the grounds that the United States cannot “absorb” large numbers without straining resources and assimilation; a historically low refugee ceiling for fiscal year 2026; and, most starkly, a State Department policy pausing immigrant visa processing for nationals of dozens of countries based on asserted “high risk” of reliance on public benefits—language that directly turns the immigrant into a potential cost center before the person is ever interviewed.

The argument of this analysis is not that the Immigration Act of 1917 and Trump-era immigration policies are identical in scope or mechanism. They are not. The 1917 law was a legislative monument produced by decades of organized restrictionism and nativist politics; today’s measures span executive orders, agency rules, program suspensions, and enforcement strategies. The claim is narrower and more consequential: that the Trump administration’s disposition toward immigrants from poor countries mirrors the logic of 1917 by reviving the same premise in modernized terms—immigrants from poorer nations are assumed to contribute less and take more, and therefore must be excluded, delayed, deterred, or subjected to special presumptions.

That premise—value as a function of origin and income—has always been politically useful because it wears multiple masks. It can present itself as national security. It can present itself as fiscal responsibility. It can present itself as a defense of workers. It can present itself as a neutral demand for “self-sufficiency.” And yet, when those masks are peeled back—when one examines which populations are targeted, which exceptions are made, which burdens are treated as disqualifying, and which stories are told about who belongs—what remains is a familiar moral calculus: the border as an audition for worthiness, with poverty treated as failure.

The 1917 Act: When the U.S. Put “Undesirability” Into Statute

To understand how a twenty-first century administration can echo a 1917 law, it helps to remember what that law actually did—and what it assumed. The Immigration Act of 1917 is often recalled for its “Asiatic Barred Zone,” a sweeping geographic exclusion that extended from the Middle East across much of South and Southeast Asia, forbidding immigration from vast territories by default. But historians of immigration policy emphasize that the barred zone, while dramatic, was only one part of a broader restrictionist toolkit. The act also imposed a literacy test on immigrants over a certain age, expanded categories of “inadmissible” people, and increased fees and administrative hurdles that functioned as economic screens.

The literacy test is a case study in how a policy can be framed as merit while functioning as exclusion. Advocates sold literacy as a proxy for readiness, assimilation, and civic competence. In practice, it was designed—after decades of lobbying by restrictionist groups—to reduce the flow of immigrants from parts of Europe associated with poverty, radicalism, and cultural difference. Literacy, in other words, became a bureaucratic stand-in for the unspoken question: which kinds of people are likely to become assets?

But the act’s most revealing feature may be less famous than its geography or its literacy. It is the law’s obsession with “public charge” and defect. In the restrictionist imagination, the poor immigrant was not simply someone seeking opportunity; the poor immigrant was a threat to the public purse and to the moral health of the nation. The statute expanded exclusion categories that cast a wide net over those considered likely to need support. And it reinforced a longstanding American tendency—well established long before 1917—to treat poverty as suspicion at the border: the assumption that certain immigrants arrive not to work and build but to depend.

This was the Progressive Era’s paradox made policy. On one side, the period produced modern public health systems, labor reforms, and new theories of social welfare. On the other, it generated a confidence that government could “improve” society through managed populations, including through eugenic ideas that blurred social prejudice and pseudo-science. Immigration restriction became one domain where those impulses fused: protect the nation by regulating its human inputs.

The U.S. State Department’s own historical framing of the period treats the 1917 act as the first “widely restrictive” immigration law, passed amid the national security anxieties of World War I and paving the way for the quota system that followed in 1924. It’s a polite formulation. What the policy machinery did, in effect, was build a formal apparatus for ranking human beings. The law assumed that whole regions—especially in Asia—could be barred categorically, while other populations could be thinned through tests and fees. It assumed that the poor and the “unfit” were not just unfortunate but socially corrosive. It cast admission as a privilege reserved for those who could demonstrate, in advance, that they would not become a public responsibility.

A century later, the U.S. is far wealthier, its social programs far larger, its labor market more complex. Yet the same logic remains easy to activate because it offers an emotionally satisfying story: there are people “out there” who want in; they are poor; therefore they will take; therefore we must stop them. The story is not merely rhetorical. In the Trump era, it has increasingly become administrative.

Trump’s First Term: The Rhetoric of Hierarchy Becomes Policy Infrastructure

Trump’s first term (2017–2021) produced a flood of immigration measures that courts, advocates, and scholars often treated as an integrated project: reduce legal immigration, deter asylum seekers, narrow humanitarian pathways, and elevate enforcement. Some of that project was justified under security; some under border management; some under labor protection. But threaded through it was a consistent suspicion of immigrants who might require help, particularly those from poorer countries.

The clearest rhetorical artifact was the Oval Office meeting reported in January 2018, when Trump reportedly asked why the U.S. was accepting people from “shithole countries,” referring to Haiti and African nations, and suggested a preference for immigrants from places like Norway. Regardless of one’s interpretation of intent, the hierarchy embedded in the remark is difficult to miss: certain countries produce the sort of people America should want; other countries produce people who arrive as problems.

That worldview did not remain talk. It aligned with a policy direction that, among other things, sought to intensify “public charge” standards—an immigration doctrine historically used to deny entry or permanent residence to those deemed likely to rely on government support. The administration’s public charge rule, finalized in 2019, was widely criticized by immigrant advocates and analyzed by policy groups as an effort that would disproportionately impact lower-income immigrants and families, chilling lawful benefit use and reshaping legal immigration toward higher-income applicants. Economists and policy analysts argued that the rule’s thresholds were so stringent that even immigrants who were largely self-sufficient could be flagged as inadmissible—a fact underscored by contemporaneous analysis noting that the rule could penalize people who were “95 percent self-sufficient.”

It is tempting to treat such a rule as a technocratic debate about fiscal impact. That temptation is exactly the point. “Public charge” has always been a technocratic mask for a moral claim: that some people’s lives are too expensive to admit. The 1917 act used that claim openly. The Trump-era public charge regime translated it into modern welfare-state anxieties.

Even in the first term, however, the deeper continuity with 1917 was visible not only in public charge but in the architecture of presumptions. The travel ban—first announced in 2017 and repeatedly revised—operated on a logic of national origin as risk category, and it disproportionately affected Muslim-majority and poorer nations. That kind of national-origin presumption is a cousin of the barred-zone mindset: whole populations treated as suspect because of where they are from.

In other words, by the time Trump returned to office in 2025, the conceptual toolkit was already assembled: national origin as proxy; poverty as proxy; “self-sufficiency” as gate; and bureaucracy as the mechanism that makes a presumption feel like process.

Trump’s Second Term: “Self-Sufficiency” as a Governing Doctrine

Trump’s second presidency began on January 20, 2025. Almost immediately, the administration moved to reshape humanitarian admissions. A White House action titled “Realigning the United States Refugee Admissions Program,” published on the day of inauguration, suspended the U.S. Refugee Admissions Program until refugee entry, in the administration’s framing, aligns with U.S. interests and does not compromise resources, safety, or assimilation. The language is revealing not only for what it says but for what it assumes. Refugees are not treated primarily as people fleeing danger; they are treated as numbers to be absorbed, as resource claims, as cultural strain. It is an old logic in modern cadence: admission is contingent on the state’s judgment that the newcomer will not be a burden.

By late 2025, the administration formalized this approach in the fiscal year 2026 refugee ceiling: 7,500, described by multiple outlets and organizations as the lowest admissions target on record. Reuters reported not only the cap itself but the controversy surrounding it, including criticism that the administration emphasized admissions for white South Africans (Afrikaners) while drastically reducing overall refugee admissions. Whatever one’s view of any particular refugee claim, the pattern is difficult to ignore: the administration simultaneously portrays refugees as difficult to “absorb” and signals preference for a narrow subset of claimants. The “burden” logic, in other words, is selectively applied.

Then, in January 2026, the administration advanced one of the most explicit “poverty as risk” policies of the modern era: a State Department pause on immigrant visa processing for nationals of 75 countries, justified publicly under the premise that applicants from certain countries are at “high risk” of reliance on U.S. public benefits or of becoming a “public charge.” Reuters reported that civil rights groups sued over the policy, describing it as a pause that began January 21, 2026, and that it affected applicants from across Latin America, South Asia, the Balkans, Africa, the Middle East, and the Caribbean. The Guardian, covering the same lawsuit, described plaintiffs’ argument that the policy relied on what they called a false premise: that immigrants from the targeted countries are likely to rely on welfare, and that the policy amounts to a sweeping discrimination disguised as fiscal concern.

The State Department’s own language, published in an official “U.S. Visas News” update last revised February 2, 2026, makes the administration’s underlying premise unusually plain. “President Trump has made clear that immigrants must be financially self-sufficient and not be a financial burden to Americans,” the page states, describing a “full review” to ensure immigrants from “high-risk countries” do not “unlawfully utilize welfare” or become a public charge.

This is where the 1917 echo becomes more than metaphor. The Immigration Act of 1917 embedded the idea that poverty and national origin could disqualify entire groups because they supposedly threatened the nation’s wellbeing. The 2026 visa-processing pause resurrects that logic with the vocabulary of modern governance: risk review, screening, vetting, fraud, and public benefits reliance. But its animating assumption is recognizably similar. “High-risk countries” functions as a stand-in for “poorer countries,” and “public charge” functions as the legal mechanism by which poverty becomes exclusion.

To see the continuity is not to deny that governments have legitimate interests in managing admission systems. It is to notice how readily the administration collapses “immigrants from poor countries” into “burden,” and how it operationalizes that collapse at scale.

The 1917 Blueprint: Proxies That Stand In for Worth

The 1917 act’s genius, in political terms, was to convert a moral preference into administrative categories. Literacy became an easily administered proxy for desirability. Geographic exclusions became a shortcut for racial hierarchy. Expanded inadmissibility categories became a way to keep out those whose poverty, disability, illness, or perceived moral failing could be framed as social cost.

The modern U.S. cannot reproduce that blueprint exactly. Constitutional doctrine, civil rights norms, and statutory frameworks impose constraints. But the logic of proxies remains. “Public charge” is the proxy of our time because it transforms a contested question—how to weigh the costs and benefits of immigration—into a presumption: if someone might use benefits, that person is less worthy.

The Trump administration’s visa pause takes the proxy logic a step further by attaching it to nationality. The policy does not simply say: we will consider public charge in individualized cases. It implies that nationality itself predicts benefits use and thus warrants collective delay. In that sense, the pause resembles the barred-zone mindset even as it is justified through fiscal language rather than explicit racial doctrine.

And the policy environment around it reinforces the same direction. The Wall Street Journal reported today on new rules intended to curtail immigrants’ ability to appeal deportation orders, reducing appeal windows and accelerating removals. This is a different part of the system—enforcement rather than admissions—but it shares a family resemblance: a governing impatience with due process when the subject is an immigrant, particularly asylum seekers and others without resources. In practice, speed and restriction disproportionately punish the poor, because wealth buys lawyers, time, and the ability to navigate a system designed to exhaust.

When taken together—refugee suspension, record-low refugee ceiling, visa processing pauses justified by welfare presumptions, and procedural tightening in removal—what emerges is less a set of discrete decisions than an ideological infrastructure. The infrastructure does what the 1917 act did: it treats the poor immigrant as a special problem requiring special restrictions.

“Poor Countries Can’t Add Value”: The Premise Beneath the Paperwork

The conclusion—that the Trump administration’s disposition mirrors 1917 because both are built on the premise that immigrants from poor countries cannot add value—demands careful parsing. Very few modern officials state this premise so bluntly. Instead, it appears as a cluster of insinuations and administrative choices.

One version appears in rhetoric that ranks sending countries by desirability. Trump’s reported “shithole countries” remark and his contrast with Norway is not a policy memo. It is, however, a statement of worldview: some countries produce people America wants; others do not.

Another version appears in the administration’s consistent emphasis on “self-sufficiency,” which is reasonable as a general aspiration but becomes ideological when deployed as a near-exclusive criterion of belonging. The State Department’s language frames immigrant admission as a potential “financial burden” and casts certain nationalities as inherently “high-risk” of benefits reliance. The lawsuit described by Reuters and The Guardian argues that the factual predicate is false and that the policy violates legal requirements for individualized adjudication under the Immigration and Nationality Act. But even if one brackets the legal debate, the moral narrative is unmistakable: poor-country immigrants are treated not as future coworkers, neighbors, entrepreneurs, caregivers, or taxpayers, but as future claimants on welfare.

This is, essentially, the 1917 argument cleaned up for a modern audience. The 1917 act did not say, in so many words, “poor immigrants cannot add value.” It said, instead, that the nation must be protected from those likely to become public charges, from the “undesirable,” from those who could not meet tests framed as readiness. The effect was to equate poverty and foreignness with social harm. Today’s policies often do the same, but with data-tinged language: risk, fraud, burden, backlog, absorption.

And yet, the most striking thing about this premise is how much evidence exists against it—evidence that has been synthesized by mainstream institutions not usually associated with open-border romanticism. In 2016, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine published a major report concluding that immigration has an overall positive impact on long-run economic growth in the United States, with complex fiscal impacts that often depend on level of government and generation. The report emphasized a crucial dynamic: while first-generation immigrants can impose costs, particularly at state and local levels due to education, the second generation tends to be a net positive, contributing more in taxes than they consume in benefits.

This does not mean every individual immigrant is a fiscal gain in the short term, nor does it negate real distributional tensions. But it does mean the blanket suspicion embedded in “high-risk country” presumptions is, at best, intellectually lazy—and at worst, a strategic use of fiscal anxiety to justify exclusion.

The question, then, is why a premise so weak on the evidence can remain powerful in politics. The answer is that the premise has never been only economic. It is cultural, racial, and moral. It is about who is imagined as “us,” and who is imagined as an expense.

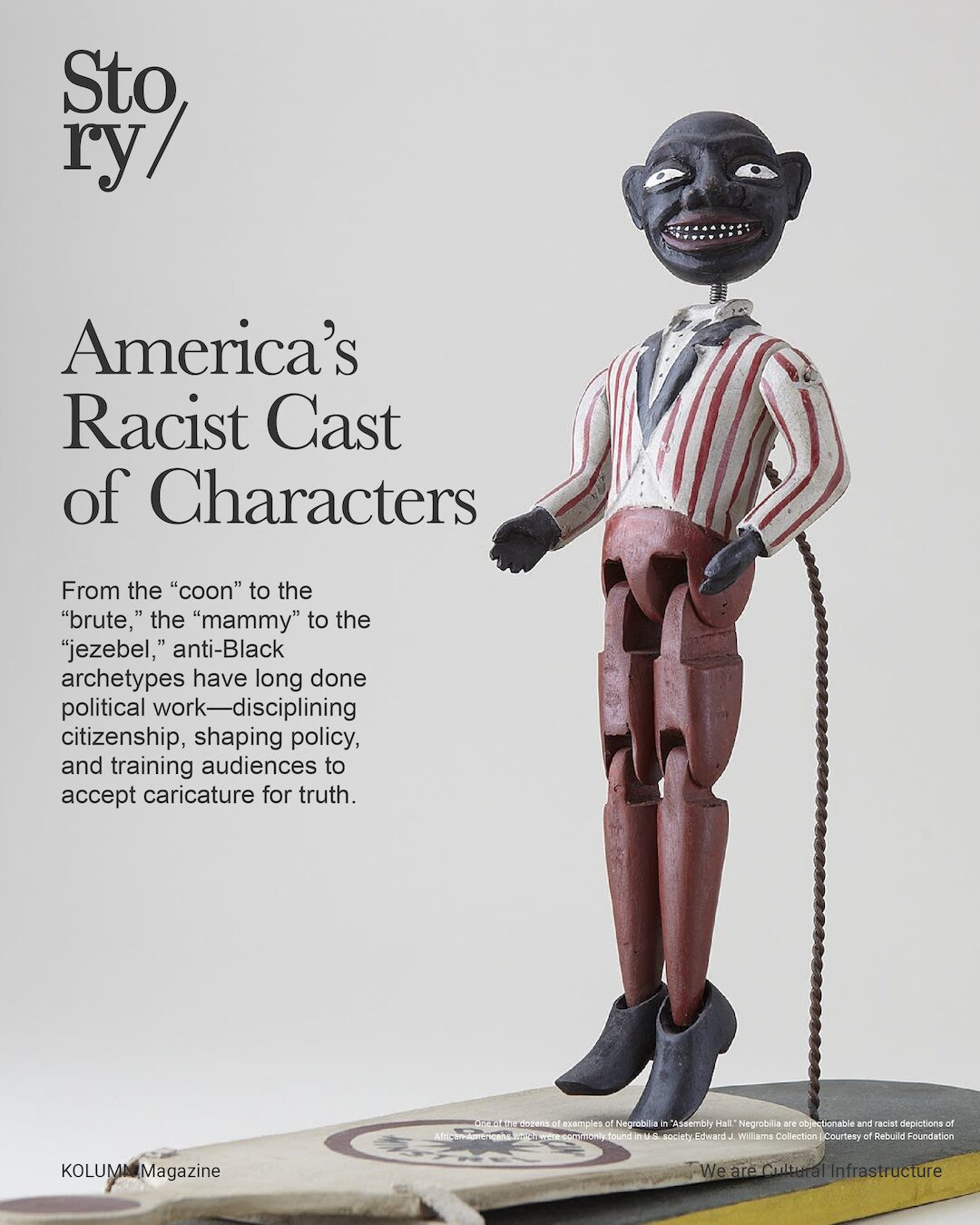

The Racial Geography of “Public Charge”

Public charge doctrine is an old tool in U.S. immigration law, predating Trump and predating 1917. It reflects a longstanding American habit: the state’s desire to select immigrants who will not require public aid. The Trump era’s innovation was not inventing the concept but expanding and weaponizing it.

Policy analysts during Trump’s first term argued that the public charge changes were structured to exclude poor immigrants and, indirectly, to exclude nonwhite immigrants from the Global South—because poverty and race are intertwined in global inequality and in U.S. migration flows. That critique did not require imputing personal prejudice to every policymaker. It required only noticing the predictable distribution of impact.

Now, in 2026, the State Department’s nationality-based visa pause makes the distribution even harder to ignore. Reuters described the pause as affecting nationals across multiple regions, including many poorer countries; The Guardian emphasized countries like Somalia, Haiti, Iran, Eritrea, and Cuba in its reporting. The policy’s moral architecture is plain: wealthier nations are not being publicly described as “high-risk” in this manner; poorer ones are.

This is where the “Immigration Act of 1917 mirror” becomes more than a historical flourish. The barred zone was a racial geography codified into law. The 2026 visa pause is a fiscalized geography, but it maps onto global inequality in ways that function similarly. One can debate the administration’s stated motivations—fraud prevention, resource management, vetting quality. But the result is still a system that treats certain nations as presumptively unworthy because their citizens are more likely to be poor.

And once poverty becomes a proxy for unworthiness, the system almost inevitably begins to treat poverty as evidence of bad character. The poor immigrant is recast as cheat, freeloader, security risk, drain. The same conceptual move animated 1917.

The Haiti Example: Poverty, Race, and the Boundaries of Sympathy

Consider Haiti, a country that has long served as a screen onto which American immigration politics projects its anxieties about race and poverty. This week, Reuters reported that a federal judge blocked the Trump administration’s attempt to revoke Temporary Protected Status for more than 350,000 Haitians, with the judge suggesting the move likely violated legal procedures and constitutional equal protection and may have been driven by bias against nonwhite immigrants. (Reuters)

TPS is not the same as immigrant visa processing, and the legal questions differ. But the moral logic is related: whether Haitians are seen as people deserving protection and a chance to contribute, or as an undesired population that should be removed once administrative patience ends. The judge’s reasoning, as described by Reuters, suggests that the fight is not only technical but constitutional—about whether the state is allowed to target a population under a veneer of neutrality when the underlying animus is racial or national-origin bias.

Haiti also sits at the center of Trump’s “shithole countries” remark, which is why it matters that the administration’s 2026 visa pause and broader posture use “public charge” logic. When the same country appears repeatedly across these episodes, the pattern is hard to dismiss as coincidence. It begins to look like a worldview being implemented through multiple levers: humanitarian status, family reunification, admissions processing, and enforcement.

This is exactly how restriction regimes consolidate. They rarely announce a single master plan. They build a landscape in which some populations face friction everywhere: longer waits, higher scrutiny, narrower discretion, fewer avenues, and faster removal.

The 1917 “Value” Test and the Modern “Merit” Story

The 1917 literacy test was a blunt instrument, but it was justified through an appealing narrative: merit. If you can read, you have demonstrated something—discipline, readiness, the capacity to integrate. The Trump era’s “self-sufficiency” focus is, in many ways, the literacy test’s descendant. Instead of asking whether an immigrant can read lines on a page, the state asks whether the immigrant’s income, assets, or projected consumption meets a threshold. In both cases, the test pretends to measure readiness. In practice, it measures class.

The State Department’s framing—“immigrants must be financially self-sufficient”—is not a neutral administrative slogan. It is a cultural statement about belonging: the immigrant must arrive already secure, already resourced, already profitable. This is, fundamentally, an attempt to rewrite the mythology of American immigration. The famous poem at the Statue of Liberty is not law, and historians rightly point out that the U.S. has long restricted the poor. But the national narrative still contains an idea—however imperfectly realized—that the country is a place where people can arrive with little and build. When policy insists that immigrants must arrive with enough, it is not only changing admissions rules. It is changing the moral story America tells about itself.

The 1917 act emerged at a moment when that moral story was being narrowed. So is the current era.

What the Evidence Says Immigrants Actually Do

The most persistent flaw in “poor country immigrants don’t add value” is that it misunderstands how value is created, distributed, and realized over time.

Immigrants contribute as workers, consumers, entrepreneurs, caregivers, and taxpayers. Their children often climb educational and economic ladders, producing exactly the intergenerational gains that the National Academies report identifies as fiscally positive by the second generation. Even debates that emphasize fiscal costs often concede that the long-run growth effects of immigration are positive.

There is also the basic reality that “poor country” does not mean “unskilled,” and “unskilled” does not mean “no value.” Modern economies depend on a vast range of labor, including essential work that is often undervalued in wages but vital in function: food production, care work, construction, hospitality, logistics. The 1917 worldview treated such laborers as suspicious because they might be poor. The modern “self-sufficiency” doctrine risks making the same mistake: confusing low income with low contribution.

The political counterargument is familiar: immigrants may contribute overall, but they can still strain particular communities, wages, or services. That is not a frivolous concern, and it deserves a policy response that invests in local capacity rather than scapegoating newcomers. But the Trump administration’s approach, judging by its own published rationale for visa pauses, frames the issue primarily as preventing immigrants from accessing welfare—rather than, say, improving labor standards, funding integration, or reforming the system Congress has left stagnant for decades.

In short, “public charge” becomes the solution not because it is the most accurate tool, but because it is the most ideologically convenient.

Why 1917 Keeps Returning: Scarcity Politics and the Performance of Control

The 1917 act did not only restrict entry. It performed control. It assured anxious voters that the government could classify, screen, and protect. It told a story of scarcity: that America’s resources were limited, and that the wrong immigrants would dilute or drain them.

That story thrives in moments of perceived disorder: war, economic transition, demographic change, cultural conflict. The current era has all of these, plus an information ecosystem in which immigration can be made to feel omnipresent and apocalyptic even when the underlying policy levers—legal categories, processing capacity, asylum law—are technical and fixable.

Trump’s second term has leaned into the performance of control. Suspending refugee admissions signals a decisive break. Setting a record-low refugee ceiling signals restraint. Pausing immigrant visa processing for 75 countries signals a willingness to disrupt family reunification and employer plans in the name of preventing “burden.” And tightening deportation appeals signals speed: less deliberation, more removal.

Each move also has an important secondary effect: it shifts the burden of proof onto the immigrant. In 1917, immigrants had to prove literacy, prove acceptability, prove they were not “undesirable.” Today, immigrants must increasingly prove they will never become costs—an impossible standard in a modern society where economic shocks, health crises, and family needs affect citizens and noncitizens alike.

What is presented as common sense—don’t admit people who will use benefits—becomes, in practice, an attempt to engineer an immigrant class that is wealthy, healthy, and low-risk. In other words: a selective immigration system that treats migration from poor countries as a problem rather than a human constant.

The Ethical Question Journalism Has to Ask

The 1917 act did not only restrict entry. It performed control. It assured anxious voters that the government could classify, screen, and protect. It told a story of scarcity: that America’s resources were limited, and that the wrong immigrants would dilute or drain them.

That story thrives in moments of perceived disorder: war, economic transition, demographic change, cultural conflict. The current era has all of these, plus an information ecosystem in which immigration can be made to feel omnipresent and apocalyptic even when the underlying policy levers—legal categories, processing capacity, asylum law—are technical and fixable.

Trump’s second term has leaned into the performance of control. Suspending refugee admissions signals a decisive break. Setting a record-low refugee ceiling signals restraint. Pausing immigrant visa processing for 75 countries signals a willingness to disrupt family reunification and employer plans in the name of preventing “burden.” And tightening deportation appeals signals speed: less deliberation, more removal.

Each move also has an important secondary effect: it shifts the burden of proof onto the immigrant. In 1917, immigrants had to prove literacy, prove acceptability, prove they were not “undesirable.” Today, immigrants must increasingly prove they will never become costs—an impossible standard in a modern society where economic shocks, health crises, and family needs affect citizens and noncitizens alike.

What is presented as common sense—don’t admit people who will use benefits—becomes, in practice, an attempt to engineer an immigrant class that is wealthy, healthy, and low-risk. In other words: a selective immigration system that treats migration from poor countries as a problem rather than a human constant.

The Long Arc of Anna Julia Cooper