The long discipline of insisting that Black presence is not a sidebar to American history but one of its load-bearing structures.

The long discipline of insisting that Black presence is not a sidebar to American history but one of its load-bearing structures.

By KOLUMN Magazine

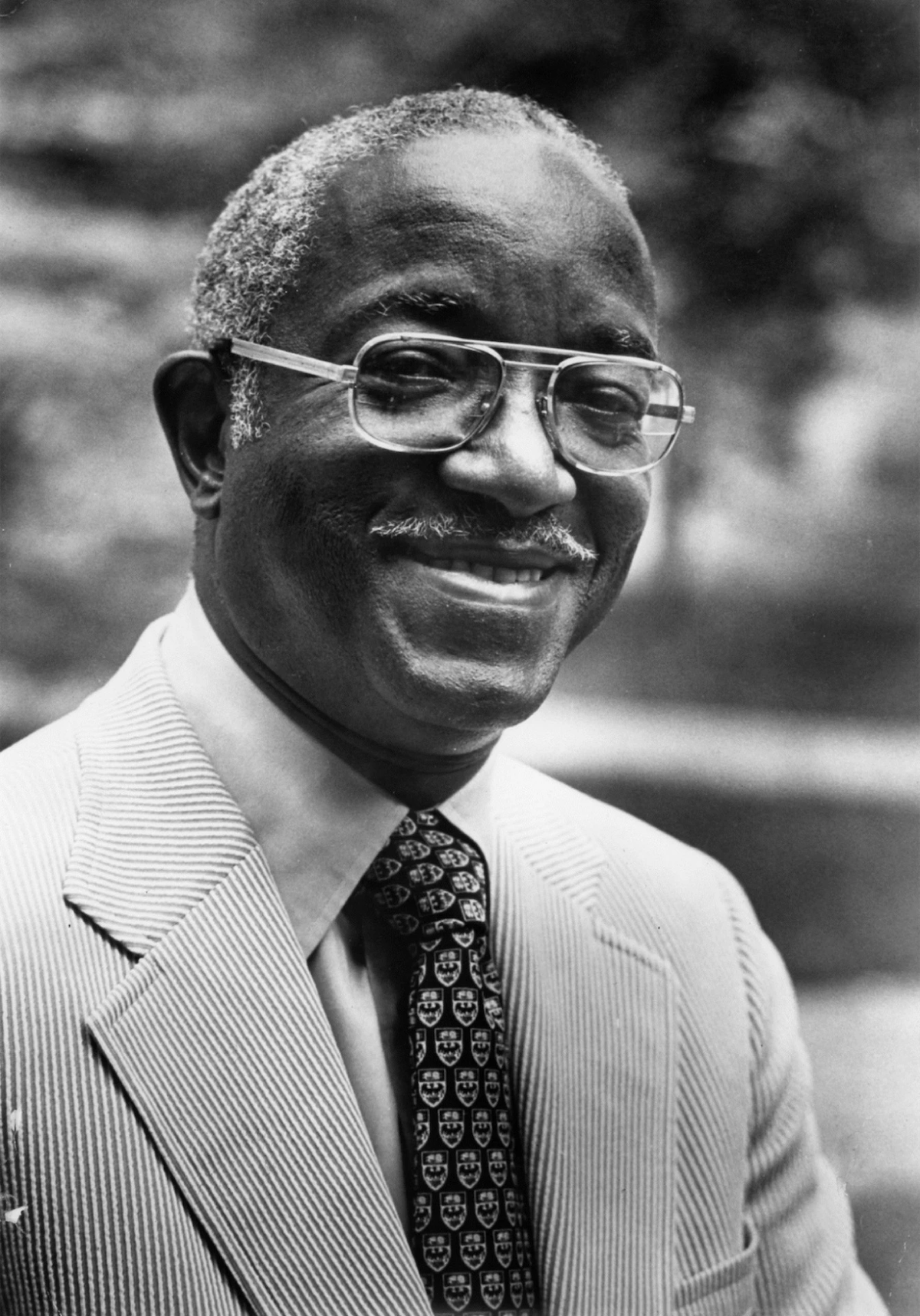

John Hope Franklin’s life reads like an argument—patiently assembled, meticulously footnoted, and delivered with the calm force of someone who has seen what happens when a nation lies to itself. He became, by wide consensus, one of the most important American historians of the 20th century: a scholar whose work helped define African American history as a rigorous field and whose public service carried that scholarship into courtrooms, commissions, classrooms, and even the ceremonial rooms of presidential power. When he died in 2009 at 94, tributes landed with a kind of moral certainty: Franklin had not simply studied the central dilemma of the United States—race—but had lived inside its machinery and refused to let the story be told incorrectly.

To write about Franklin is to write about craft—how a historian builds a narrative sturdy enough to hold a nation’s contradictions. But it is also to write about courage: the long discipline of insisting that Black presence is not a sidebar to American history but one of its load-bearing structures. “My challenge,” he said in one of his oft-cited formulations, was to weave the presence of Black people into the fabric of the national story so the United States could be told “adequately and fairly.” It is difficult to improve on that sentence as a mission statement for his life.

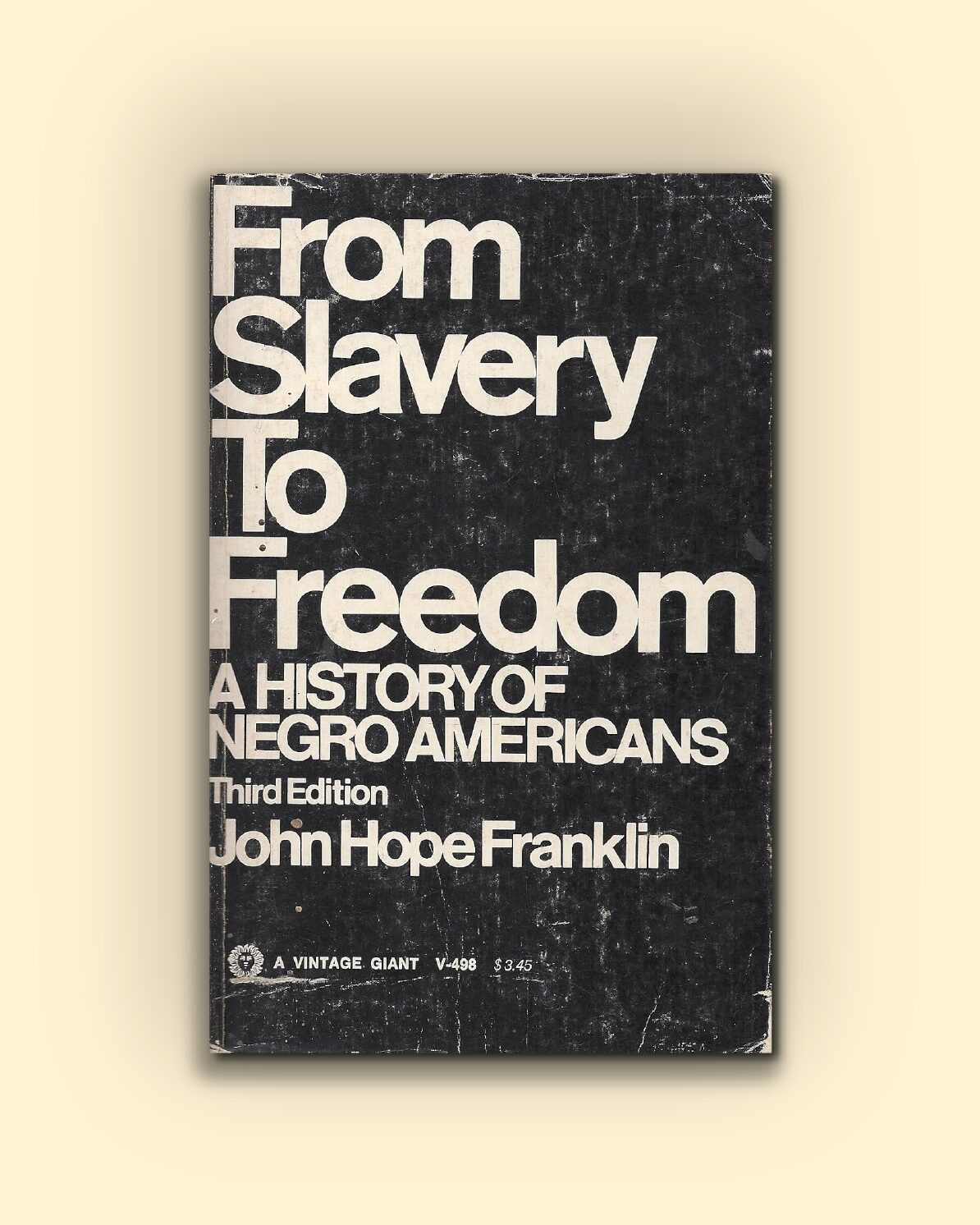

Franklin’s signature accomplishment—From Slavery to Freedom—did something deceptively simple: it offered a comprehensive, accessible, and scholarly narrative of African American history and placed it in the center of the American experience. First published in 1947 and repeatedly revised across decades, the book became a standard text, shaping how generations of students, teachers, journalists, and general readers understood the country.

But Franklin’s impact can’t be reduced to a single title, however foundational. He moved through the most consequential institutions of American intellectual life—universities, professional associations, national commissions—often as a first, sometimes as a corrective, always as a standard-setter. He advised civil rights litigation, helped frame public conversations about race at the highest levels of government, and modeled a role that scholars still debate: the historian as public actor, not merely a commentator.

In an era when fights over curriculum, “patriotic education,” and historical memory have become a kind of proxy war for political power, Franklin’s career feels less like a chapter in the past than a playbook for the present. He believed that history was not simply descriptive—an elegant arrangement of what happened—but prescriptive in the most democratic sense: the shared record by which a people holds itself accountable.

Oklahoma beginnings, and the shadow of Greenwood

Franklin was born in Rentiesville, Oklahoma, in 1915, in a state—and a region—where Black towns, Black aspiration, and white backlash existed in uneasy proximity. The family moved to Tulsa when he was a child, and that relocation placed him near one of the most notorious eruptions of racial violence in U.S. history: the 1921 destruction of the Greenwood District, often referred to as “Black Wall Street.” His father, Buck Colbert Franklin, was a prominent attorney who represented Black survivors after the massacre. That proximity mattered—not as an origin myth, but as a formative reality: the lesson that citizenship could be revoked by mob and policy alike, and that law and documentation might be among the few tools left to contest the revocation.

Franklin’s later life repeatedly returned to Tulsa—not only in memory but in public commemoration. Tulsa ultimately named its reconciliation park in his honor, a civic acknowledgment that the work of repairing historical trauma requires stewards of truth as much as it requires monuments.

This Oklahoma beginning is important because it complicates a common way America talks about the Black freedom struggle—as though it is primarily a Southern story with a few northern stages. Franklin was shaped by a borderland reality: western expansion, Native dispossession, Black settlement, and modern segregation braided together. That complexity later surfaced in his scholarship, which resisted tidy regional moral maps. (Even his family history—often discussed in biographies—touches the entanglements of race and Native identity that conventional U.S. narratives flatten)

Training for the archive: Fisk University and Harvard University

Franklin’s formal path into history ran through institutions that both nurtured Black intellect and tested its limits. He earned his undergraduate degree at Fisk University, then moved to Harvard University for graduate study, completing a Ph.D. in history in 1941.

Those years mattered not only because they supplied credentials—though credentials were crucial in a country where gatekeeping was an operating principle—but because they trained Franklin in the methods that would become his weaponry: archival discipline, interpretive restraint, and an insistence that arguments must survive contact with primary sources. He was not a polemicist by temperament. He could be blunt, but he built bluntness on evidence.

The irony, and the point, is that the very academic structures that helped produce Franklin were also structures that had spent decades marginalizing the subjects he would elevate. In this sense, Franklin’s career embodies a quiet insurgency: mastering the tools of a discipline and then forcing the discipline to confront what it had excluded.

A book that changed the syllabus: From Slavery to Freedom

When Franklin published From Slavery to Freedom in 1947, the U.S. was barely two years removed from the end of World War II, and American democracy was busy congratulating itself. The country’s self-image—freedom abroad, progress at home—was increasingly difficult to maintain in the face of segregation, disenfranchisement, and racial violence. Franklin’s book arrived as a corrective to national amnesia.

The achievement of From Slavery to Freedom was not merely that it chronicled Black life from enslavement through emancipation and beyond. It was that Franklin treated African American history as inseparable from the nation’s political and economic development. The book refused the temptation to make Black history a moral supplement—uplifting, tragic, inspirational, adjacent. Instead it described a people and a struggle as constitutive of the American project itself.

Its durability tells you something about both Franklin and the country. A text doesn’t remain foundational for decades unless it is both intellectually robust and institutionally useful: something teachers can assign, students can read, and scholars can respect even when they argue with it. Duke’s own institutional biography notes that the work continued to be updated, with later editions incorporating new scholarship and co-authorship, a sign that Franklin saw historical narration as a living project rather than a closed case.

But durability also signals a more unsettling truth: the hunger for a comprehensive African American history textbook existed because the canon had left a vacuum. Franklin helped fill that vacuum with a structure strong enough to hold both the grandeur and brutality of the American story.

Scholar-activist in the most literal sense: NAACP Legal Defense Fund and Brown

Franklin’s name belongs not only on book spines and faculty rosters but also in the documentary history of civil rights litigation. In the early 1950s he joined the NAACP Legal Defense Fund research effort connected to the cases that culminated in Brown v. Board of Education.

This detail is sometimes told as an impressive footnote: the eminent historian helped the lawyers. But it is more revealing when you treat it as a statement of method. Civil rights strategy required more than moral claims; it required historical argumentation—evidence about the meanings of citizenship, education, and equal protection as they had developed over time. Franklin was part of a broader effort to make history admissible as a form of proof.

Accounts from historians’ organizations describe how Thurgood Marshall turned to Franklin for historically grounded analysis, including work connected to understanding the Fourteenth Amendment in the context of school desegregation litigation.

Franklin understood something that remains relevant: in America, the fight over rights is often a fight over narrative—over what the past authorizes. If you can constrain the past to a convenient story, you can constrain the present’s obligations.

The institutions he entered—and changed: University of Chicago and Duke University

Franklin held appointments at multiple institutions over a long career, including University of Chicago and later Duke University, where he became closely identified with both the university and the wider civic life of Durham.

It is easy to say he “taught” at these places and move on. A more precise way to describe it is that he integrated spaces of authority. When universities welcomed Franklin, they gained not only a scholar but a moral benchmark—someone whose presence exposed how late and how reluctantly many elite institutions had admitted Black excellence on equal terms.

Duke’s remembrance of Franklin emphasizes his role in transforming the field of African American history over nearly six decades. The language is institutional, but the implication is personal: Franklin’s career forced universities to recognize that the story they were telling about America, and about themselves, was incomplete.

His influence persists in the infrastructure that carries his name: Duke’s John Hope Franklin–affiliated initiatives and collections, including a research center in the library dedicated to sources on the histories and cultures of Africa and the African diaspora in the Americas. These are not ornamental honors; they are pipelines for scholarship—the kind of structural legacy Franklin spent his life building.

Public history at presidential altitude: Bill Clinton and the “One America” initiative

In 1997, Franklin became chair of the advisory board for Bill Clinton’s Initiative on Race—often referred to as “One America.” The appointment was symbolic and strategic: a scholar whose work had defined the nation’s racial history was now being asked to help frame a national conversation about race at a moment when demographic change, culture-war politics, and the aftershocks of civil rights gains were colliding.

Archival White House materials describe Franklin’s credentials and positioning: a senior historian with deep ties to academia and law, capable of translating scholarship into public deliberation.

There is a temptation to treat such commissions as ceremonial—panels that generate reports and then vanish into shelves. But even that would miss Franklin’s larger significance. His presence signaled that the federal government, at least momentarily, recognized that race was not a temporary “issue” but a central organizing fact of American life—one that required historical literacy, not merely political messaging.

The very premise of a presidential race initiative also hints at the country’s recurring pattern: confronting race only when crisis makes avoidance impossible, then declaring the conversation complete as soon as it becomes uncomfortable. Franklin, who had studied Reconstruction and the post–civil rights backlash in various forms, was acutely aware of that pattern.

The honors—and what they signified

Franklin accumulated nearly every major form of recognition available to an American historian, including the Presidential Medal of Freedom and the John W. Kluge Prize.

These awards were not merely lifetime-achievement ornaments. They represented a shift in what the nation was willing to honor. A scholar who insisted on “unvarnished truth” about slavery, segregation, and the architecture of racial inequality was being recognized as a civic asset rather than a national scold. That is not a small change; it suggests Franklin’s success in making historical honesty a form of patriotism—one grounded in responsibility rather than myth.

The professional associations echo this stature. In memorial reflections, the American Historical Association describes Franklin as a “scholar and mirror to America,” emphasizing not only his academic contributions but also his public engagement and leadership across historical organizations.

Innovation as method: How Franklin made a usable history without flattening it

When people hear “innovation,” they often look for gadgets or disruptive formats. Franklin’s innovations were methodological and institutional—changes in how history is researched, narrated, and legitimized.

One innovation was his insistence on synthesis as a serious scholarly act. In many academic settings, synthesis is treated as secondary to specialized monographs: important for teaching, less prestigious for tenure. Franklin reversed that hierarchy by producing a synthesis (From Slavery to Freedom) so authoritative that it became a gateway into the field itself. He demonstrated that to write the big story responsibly requires extraordinary command of the small stories.

Another innovation was his model of the historian as an expert witness for democracy. By contributing to civil rights legal strategy and later advising national conversations on race, Franklin helped establish a template that is now more common: scholars whose expertise is relevant to policy and public life without becoming reducible to partisan actors. The danger of such work is simplification; the discipline is refusing to simplify. Franklin’s career is instructive precisely because he managed, more often than not, to bring complexity into arenas that reward slogans.

A third innovation was infrastructural: building archives and institutions that outlast the scholar. Duke’s collections and institutes bearing Franklin’s name are examples of how prestige can be converted into capacity—funding, staffing, collecting, programming. Franklin understood that memory requires maintenance, and maintenance requires institutions.

The personal life that shaped the public one

There is a risk, in writing about a figure as decorated as Franklin, of letting honors replace humanity. Some of the most revealing details about him are disarmingly ordinary—and therefore clarifying.

One recurring story, highlighted in commentary around his death, involves Franklin being denied service at a hotel despite his status—an incident that condensed a lifetime’s theme: credentials do not inoculate Black Americans against humiliation, and “progress” is often less secure than the nation imagines.

Another detail, noted in profiles and cultural essays, is Franklin’s devotion to cultivating orchids with his wife, Aurelia Whittington Franklin—a long marriage that anchored a demanding public career. The fact becomes more than charming trivia when you read it as evidence of temperament: patience, careful tending, faith in growth over time. It is hard not to see the metaphor.

And then there is the bluntness of Franklin’s public ethic, a line often quoted in institutional remembrances: the demand for truth without cosmetic comfort. A Fulbright remembrance points to his words displayed at the National Museum of African American History and Culture: the insistence on telling “the unvarnished truth.” Whatever one thinks of commemorative quotation culture, the phrase fits Franklin because it captures his governing idea—history as civic honesty, not therapy.

How the press and public remembered him

Major outlets framed Franklin as both chronicler and participant. The Washington Post called him “the master of the great American story” of race—language that risks grandiosity but also recognizes something accurate: Franklin did not merely recount events; he supplied interpretive coherence for a century’s worth of conflict and change.

The Guardian leaned into the duality: Franklin as pre-eminent chronicler of race and also a “battler for equality,” a scholar whose authority was inseparable from his commitments.

Meanwhile, discipline-specific tributes from historians underscored his leadership and his unique legitimacy within the profession. The American Historical Association’s memorial materials cataloged not just his books but his service—presidencies of major historical organizations, national commissions, and the particular stature that allowed him to serve as a bridge between academic history and public responsibility.

Black-focused outlets added texture that mainstream elegies sometimes miss. Ebony has invoked Franklin’s authority in the context of Tulsa and Black Wall Street, situating him as both a product of Oklahoma’s Black history and a narrator of its national significance.

The Root has preserved more intimate and interpretive reflections—from centennial remembrances to recordings and essays that treat Franklin as a lineage figure, a “prince” in a tradition of Black historians who forced elite institutions to confront Black intellectual power.

And Word In Black, reporting on contemporary cultural work that draws on Greenwood’s afterlife, signals how Franklin’s name remains part of Tulsa’s living civic language—tied to reconciliation efforts and educational initiatives that are still unfolding.

Legacy in a contested present

Franklin’s legacy is sometimes summarized as a set of firsts and honors: first-rate historian, first Black president of key professional bodies, recipient of major national awards, advisor to presidents. But the deeper legacy is his insistence that democracy depends on historical clarity.

That sounds like a lofty abstraction until you place it in the current environment—where political actors openly fight to control what can be taught about slavery, Reconstruction, segregation, and their afterlives. Franklin anticipated this conflict because he had spent a career studying how historical distortion functions as governance. When you deny the past, you deny claims for repair; when you sanitize the archive, you sanitize responsibility.

Franklin’s work offers no cheap comfort. It does not promise that the arc of history bends automatically toward justice. It argues, instead, that progress requires attention, organization, and an honest accounting—precisely the kind of accounting that makes many societies uneasy. His life also suggests that institutions can change, but rarely on their own schedule; they change when people like Franklin insist, persistently, that they must.

In that sense, Franklin’s most important innovation may be the one least celebrated: he made truth-telling look like a professional standard rather than a personal pose. He showed what it means to write history that is both usable and unsentimental—history that can serve the public without flattering it.

The historian’s quiet demand

There is a temptation, especially in commemorative writing, to resolve the story into uplift: look how far we’ve come. Franklin resisted that kind of ending. His own career—spanning Jim Crow, civil rights, backlash, and the opening of new possibilities—made him wary of premature closure.

If you want a Franklin ending, it is not triumphalist. It is procedural. It sounds like a directive to the next generation of scholars, teachers, editors, and citizens: do the work, check the record, tell the truth, build institutions that can hold the truth, and don’t mistake recognition for completion.

He understood, perhaps better than most, that the United States is always tempted by the seductions of forgetting. His life’s work was to make forgetting harder.

The Long Arc of Anna Julia Cooper